Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2383

March 20, 2011

The War On Telephones

The ongoing death of the phone call is one of the great triumphs of our time:

"I remember when I was growing up, the rule was, 'Don't call anyone after 10 p.m.,' " Mr. Adler said. "Now the rule is, 'Don't call anyone. Ever.'"

Indeed. I really wish competition among cellular operators was robust enough that it would be possible to buy a smart phone with data and SMS but no voice plan whatsoever.

The Endgame In Libya?

I share my colleague Brian Katulis' concerns:

"There was this premature triumphalism about the passage of the UN resolution but what is the plan for dealing with this entity called Libya?" says Brian Katulis at the Center for American Progress, a Washington-based think-tank.

"You could have this very awkward phase emerging where Gaddafi is entrenched while there's a rump state in eastern Libya and some but not all states in the Arab world work to isolate the regime."

Conversely, what if the injection of western airpower is massively successful and Gaddafi's regime collapses. That doesn't mean an automatic transition to a new stable state. Does the "Pottery Barn Rule" apply if a chaotic scenario develops?

March 19, 2011

Early Adventures in Constitutionalism

The high-speed rail debate of the early 19th century concerned canal construction, and in 1817 James Madison vetoed a canal bill, explaining that it's unconstitutional for the federal government to spend money on transportation infrastructure:

The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers, or that it falls by any just interpretation with the power to make laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution those or other powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States.

"The power to regulate commerce among the several States" can not include a power to construct roads and canals, and to improve the navigation of water courses in order to facilitate, promote, and secure such commerce without a latitude of construction departing from the ordinary import of the terms strengthened by the known inconveniences which doubtless led to the grant of this remedial power to Congress.

I would have said that the power "[t]o establish Post Offices and Post Roads" implies a generic grant of authority to do transportation.

Franchise Value

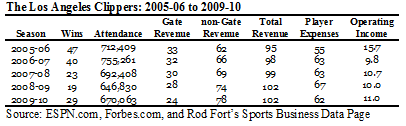

The horror of the NBA, it seems to me, is that it's one of the rare businesses in which a firm that's persistentlyT mismanaged and constantly failing can nonetheless be a profitable business. Take the LA Clippers:

Forbes.com doesn't just report basic revenue and cost data. They also attempt to estimate franchise values. And according to their estimate, the Clippers are worth a bit more than $300 million today. Donald Sterling bought this team in 1981 for $13 million. So if we focus just on the change in franchise values (and ignore yearly profits), Sterling has earned about an 11.5% annual return on his investment. Remember, the Clippers have been losers in virtually every season Sterling has owned the team. Yet despite being unable to give his customers a very good product, Sterling is still making a healthy return on his investment.

In a European-style promotion/relegation system, the Clippers wouldn't be nearly this valuable—they'd have been pushed out of the top-ranked hoops league years ago, thus forfeiting the bulk of the franchise value that comes from operating an NBA team.

Productivity and Compensation

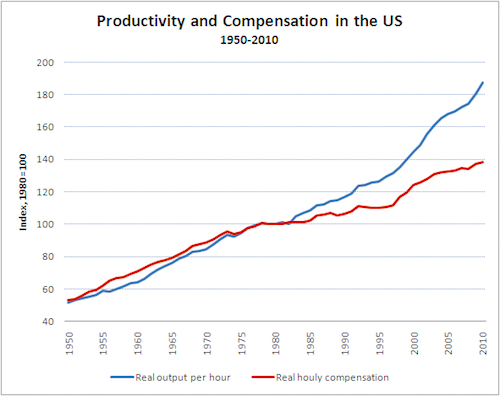

Good chart from Kash:

A healthy share of this is clearly the growing role of mega-rich financiers. Another chunk of it is superstar entertainers. But as Mike Konczal suggests, I think Federal Reserve policy is another important driver here. You had a period when real compensation grew faster than productivity, then you had a span of stagflation, and then we've had a long period wherein wages basically don't increase in part because the Fed doesn't want wages to increase.

The War of Ideas

I still don't know why the Obama administration was so quick to accept defeat in the war of ideas, but the fact is that it surrendered very early in the game. In early 2009, John Boehner, now the speaker of the House, was widely and rightly mocked for declaring that since families were suffering, the government should tighten its own belt. That's Herbert Hoover economics, and it's as wrong now as it was in the 1930s. But, in the 2010 State of the Union address, President Obama adopted exactly the same metaphor and began using it incessantly.

This is, I think, overly focused on the person of the president. It's worth delving into Krugman's wonkish post on "Credibility and Monetary Policy in a Liquidity Trap (Wonkish)" to get a better understanding of what the relevant ideas are here:

Via Mark Thoma, Mankiw and Weinzierl have a paper (pdf) arguing that fiscal expansion shouldn't be the tool of choice even at the zero lower bound; that monetary policy can still work if you can credibly make commitments about future monetary policy. As they acknowledge, the potential role of expected future money isn't a new insight; it was at the heart of my original analysis, and it's a central theme in Eggertsson and Woodford (pdf). [...]

Now bear in mind that in order to make a commitment to inflation work, central bankers not only have to stand up to the pressure of inflation hawks — which is much harder when you're having to testify to Congress than it is if you're a Harvard professor — but, even harder, they need to convince investors that they'll stand up to that pressure, not just for a year or two, but for an extended period. [...]

I supported fiscal expansion in 2008-2009 precisely because I didn't believe that the kind of commitment-based unorthodox monetary policy that works in the models could, in fact, be implemented in practice. Nothing I've seen since has changed my views on that subject.

Think of a room containing Barack Obama, David Axelrod, Jon Favreau, and Christina Romer where they're trying to work out how to explain the Obama administration's economic policies to the public and Romer offers that analysis above. Is it so hard to understand why we didn't hear this in a State of the Union address? Instead we had a war of naive metaphors ("jumpstart" the economy vs "everyone needs to tighten their belt") and since unemployment got way higher than the administration forecast, their naive metaphor was discredited. The lesson here is that discretionary fiscal policy on the scale recommended doesn't seem any more implementable than monetary expansion on the scale recommended. We need to think through the implications of that, which I think includes reforming state/local budgeting ("automatic stabilizers") and setting an inflation target higher than 2 percent so it becomes much less likely that the zero bound issue will arise.

Central Planning in the Urban Retail Economy

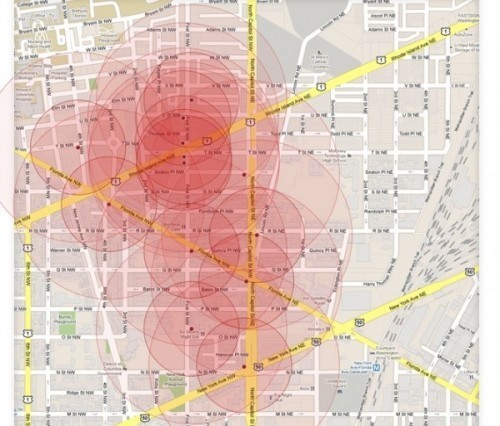

Here on the Prince of Petworth blog is what purports to be a map of liquor stores in DC's Bloomingdale neighborhood, though in fact it proceeds by counting every store licensed to sell beer as a "liquor store."

So for today's Friday Question of the Day – at what point does a neighborhood have too many liquor stores? Now I'm wondering if there is a historical component here – as many liquor stores also function as corner stores/bodegas. I assume they proliferated for convenience and perhaps a lack of access to proper grocery stores? But in 2011 given the state of our neighborhood's access to grocery stores and the existing corner stores – at what point are there too many liquor stores? Should there be moratorium? Or should capitalism work this problem out?

I'm going to vote for capitalism here. Free markets have some flaws, but assessing the market demand for retail beer sales (again, if this were an actual map of liquor stores we could talk about liquor) and supplying a roughly appropriate number of beer retailers is exactly what free markets are good at doing. If anything the evidence suggests to me that the DC government is too stingy with these licenses and is allowing a lot of storefronts to stand vacant when convenience stores could be profitably operated.

Now if your concern is that demand for beer is undesirably high, the right proposal would be higher excise taxes on alcohol. I think there's a lot of evidence that this would be good policy. But this is very different from trying to assert that somehow the market is incapable of matching the actual level of demand for beer vendors to the demand for beer.

March 18, 2011

Why Context Matters

So I guess I agree with Jon Chait that the fact that the US isn't using its influence over the Saudi or Bahraini governments to halt the killing of non-violent protestors there isn't a reason to decline to intervene in Libya. Similarly, the fact that we're not using our influence over the Yemeni government isn't a reason not to intervene in Libya. Nor is the fact that we're declining to deploy our military to restrain civil conflicts in Congo or Chad or Cote D'Ivoire exactly a reason not to intervene in Libya. And by the same token, the fact that the invasion of Iraq turned into a costly and bloody fiasco doesn't show that intervening in Libya is futile. Nor does the mere fact that American public policy is utterly indifferent to the interests and human rights of Palestinian Arabs mean an intervention in Libya is unworkable. Nor does the fact that our most recent military incursion into Africa led to the total destabilization of Somalia have any particular bearing on the merits of no-fly zone in Libya.

But there's a question of context here. Chait says: "Should we also spend more money to prevent malaria? Yes, we should. But I see zero reason to believe that not intervening in Libya would lead to an increase in in American assistance to prevent malaria."

And of course that's true too. But all this context is relevant as an indictment of the elite leadership class of the United States of America. If everyone cares as much about the political rights of Arabs as Libya interventionists say, then what on earth are they doing in Bahrain and Yemen and Palestine? If everyone cares as much about the loss of innocent African life as Libya interventionists say, then what on earth are they doing ponying up so little in foreign aid and doing so little to dismantle ruinous cotton subsidies? These aren't really points about Libya. And why should they be? What do I know about Libya? What does Chait know about Libya? These are points about the United States of America and the various elites who run the country and shape the discourse. Exactly the kinds of subjects that frequent participants in American political debates know and care about. I see no particular reason to think that Libya will have any impact on malaria funding, but I do think the level of malaria funding is impacted over the long term by the existence of a substantial number of people (of which Chait is one) who seem to advocate for humanitarian goals in Africa if and only if those goals can be advanced through the use of military force to kill other Africans.

So I hope this Libya policy works out. I have my doubts, but who knows. The world is full of surprises. I do know, however, that providing more bed nets to prevent malaria would be cheap and logistically simple compared to deposing Gaddafi and that the easiest step America could take to deal a blow to Arab autocracy would be to stop selling weapons to Arab autocrats that they turn around and fire on their people.

Endgame

Il m'a tenu chaud:

— Nukes or renewables: maybe we do have to choose.

— 42 percent of DC's land is in the Northwest "quadrant."

— Local busybodies worried about "towering" five story buildings coming in across the street.

— Where the different Obamaland players came down on Libya.

Almost as good as March Madness, it's Stereolab "Munich Madness".

Before There Was Chili's

After scarfing down a quesadilla from the Chili's Too (which apparently is what Brinker International calls Chili's outlets that don't serve babyback ribs) between flights at the Milwaukee Airport yesterday evening, I was all prepared to start thinking up a post on the baleful impact of travel on the American diet. Then I got on the plane and read this in Daniel Walker Howe's What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848:

The American of 1815 ate wheat and beef in the North, corn and pork in the South. Milk, cheese, and butter were plentiful; potatoes came to be added in the North and sweet potatoes in the South. Fruits appeared only in season except insofar as women could preserve them in pies or jams; green vegetables, now and then as condiments; salads, virtually never. (People understood that low temperatures would help keep food but could only create a cool storage place by digging a cellar.) Monotonous and constipating, too high in fat and salt, this diet nevertheless was more plentiful and nutritious, particularly in protein, than that available in most of the Old World. The big meal occurred at noon.

This is a far cry from the Pollanesque wonderland of good eating that we're sometimes told existed before fast food and microwaves ruined everything. I wonder if this doesn't kind of run in cycles with income. You start out very poor, eating crap. Then as the country gets richer, you start eating better stuff. But then you get rich enough to hire other people to cook for you, but the best way to make that economical is to make the food crappy. But then if incomes continue to rise the quality improves again.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers