Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2363

April 8, 2011

Against Term Limits

I wrote yesterday afternoon about elitist opposition to democratic accountability, but the same phenomenon also has a populist guise in the form of, among other things, term limits endorsed this week by seven of the nine people running for DC's open at large city council seat.

Term limits for the chief executive make a certain amount of sense in a developing country trying to establish democratic institutions. But despite their popularity, they have no legitimate role in a stable advanced democracy. Voters should keep being represented by the same person until either the voters get sick of the person or the person gets sick of the job. That's democracy. What happens when you contravene democracy by introducing term limits, is that practical power shifts into the hands of unelected staffers (to the extent that they're available) and unelected lobbyists (who are always plentiful). Legislating isn't child's play, after all, you need to have some familiarity with the issues and the process. Extra power naturally flows to veterans. In a democratic legislature, may of the veterans are veteran legislators—elected officials. In a limited legislature, the only veterans are the staffers and the lobbyists. But that doesn't change the fact that the veterans have knowledge and knowledge is power.

And at the executive level, who among us is really happy that Al Gore ran in 2000 instead of Bill Clinton? Who did that help?

April 7, 2011

Endgame

Everything around me is just falling down:

— What a government shutdown doesn't achieve.

— The GOP's alleged Dukakis problem (I don't buy it).

— Why publication bias matters.

— Taking Joss Whedon's feminist cred down a peg (or maybe not).

— .

Aloe Blacc, "I Need a Dollar" to continue the federal government's operations.

Gridlock and Democracy

(cc photo by kevindooley)

Mark Kleiman writes about a friend who's a great admirer of East Asia's successful autocracies and observes that disdain for democracy is "not a viewpoint often seen in print; I wonder how widespread it is?"

My sense is that in a sublimated way, anti-democratic sentiments are very common among the American elite. This is one reason why there's such tenacious support for counter-majoritarian elements of the legislative process. If major legislative change requires agreement between the leadership of both major political parties, then elections have very little efficacy in terms of determining policy outcomes. To my way of looking at it, that's a bad thing because it undermines democratic accountability. But if you don't believe in democratic accountability, it's a good thing because essentially the same relatively small group of senatorial pivot points determine the outcome at all times. Of course this also generates a massive status quo bias that the elite often dislikes in one respect or another. But instead of proposing to alleviate the status quo bias by making the institutions less bound to the status quo, the conventional wisdom is that we need more bipartisan commissions to further ensure that decision-making is divorced from electoral accountability.

I think all that's nuts. I'm not much of a populist, and it's not that I think the masses have all the answers (if you look at polls it's clear that public opinion is confused about a great many things) but I really do think that democratic accountability is very important. People who win elections should govern, and if the results of their governance are bad they should lose power. That's an incentive-compatible mode of governance. Something like "procedure nobody understands determines outcomes, and the party that doesn't hold the White House benefits from bad results no matter who was responsible for them" is not.

The Trouble With Taxing Exclusively The Rich

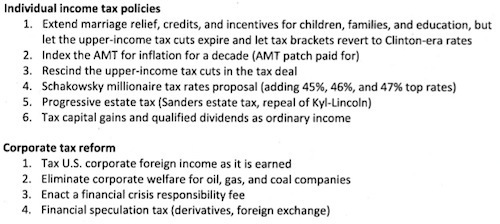

In their sketch version of a budget (PDF) the Congressional Progressive Caucus makes a heroic effort to finance progressive government basically exclusively by raising taxes on rich people.

Specifically:

The big problem I have with this is that if you raise high-end marginal rates while leaving deductions alone, what you do is massively increase the value of the deductions. The home mortgage interest tax deduction, for example, is both distributively regressive and also economically damaging by shunting too much money into the housing sector. If wealthy people start paying a marginal income tax rate of 47 percent, then the incentive to overconsume housing becomes much more intense. A economically sound approach to the tax code needs to go after some of these deductions, and that means some middle class families will have to pay somewhat more.

Not so much a problem, but an observation, about this plan is that it actually does implicitly recognize the non-viability of a rich people only strategy. After all, even though the legal incidence of these corporate tax changes is on the corporations, the reality is that some of the bite will be felt by middle class consumers of these firms' products and middle class employees of the firms. We really shouldn't be handing out so much corporate welfare to oil and gas companies. But it's not like everyone working in the oil and gas industry is an evil fatcat, it's mostly regular everyday folks. And that's fine. But once you're willing to concede the point that pursuing increased revenue in a sensible way will entail some sacrifice by some middle class people, you may as well apply that principle to the individual income tax as well as the corporate income tax.

Some Conceptual Distinctions in the Entitlements Controversy

Unfortunately, a lot of discussions of Social Security and Medicare end up running together a number of different issues that it would be smarter to keep separate. The nation is simultaneously debating how to deal with demographic change, how large a share of national income should go to the support of the elderly, how large a share of support for the elderly should take the form of health insurance, and how best to organize the provision of health insurance to the elderly. What follows is long and I'll put it below the fold.

To take the first issue first, one of the main things the United States government does is provide a measure of retirement security to elderly Americans. Currently the ratio of elderly Americans to overall population is projected to rise. This could—and should—be dealt with through higher levels of immigration, but the political system seems unwilling to admit that American demographic structure is being upheld by a large and expensive apparatus of coercion that we can modify or dismantle any time we feel like it.

The second issue is hard to parse. I'm a cold-blooded technocrat by nature, and in GDP terms dedicating a large share of national income to the elderly is pointless. At the same time, it seems to me to be welfare enhancing. I like the idea of society taking the fruits of higher productivity in the form of luxurious retirement. But I don't know what kind of objective criteria are supposed to be referenced in a debate on this subject.

Another issue over and above the question of how many resources to give to the elderly is what share of those resources should be earmarked specifically for health insurance. Here I dissent from the conventional wisdom and think the correct answer is "a small share." I'd rather give grandma $10 than $10 worth of health insurance. Paternalism makes the least sense when we're talking about elderly people. There is, of course, the important Kenneth Arrow argument from "Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Healthcare" (PDF) that adverse selection causes insurance market failures that the government can beneficially correct. I accept that argument (this is why I favor universal health care) but note that it applies with unusually little force to the elderly (whose health status is relatively certain) not unusually strong force as implied by current practice.

Last is the question of how insurance should be structured. The point of insurance is to pool risk, so if the public sector is going to provide for insurance it ought to provide for a single risk pool containing everyone. This is what Medicare currently does and it's what's known as "single-payer health care."

What's happening currently in the United States is that along with demographic change, health care costs are growing much faster than the economy as a whole. This is causing two shifts. One is that thanks to the combination of our commitment to Medicare and health care cost growth, the share of national resources going to the elderly is growing. Another is that thanks to the combination of our commitment to Medicare and health care cost growth, the share of elderly-focused resources that are devoted to health insurance is growing.

All Rationing Is Self-Rationing

Suzy Khimm writes that "Some Republicans are now casting Rep. Paul Ryan's budget plan as a form of 'self-rationing' that would place such decisions in the hands of private citizens, rather than cold-hearted bureaucrats."

What I never understand about this is that all "rationing" is self-rationing. If we have a single-payer system that's only willing to pay for certain services, then citizens are still free to pay out of pocket for other things. The fact that Medicare won't pay for a MacBook Air doesn't mean that grandpa can't buy a MacBook Air, it just means he has to spend his own money on it if he wants one. Cato's Michael Tanner tells Politico that "The question's going to be, is that decision going to be made by government and imposed top down under the current system? Ryan wants to shift that responsibility to individuals and from the bottom up."

But this isn't the question at all. Under any conceivable system there are some things that the federal government will pay for, and other things people will buy on their own.

I think conservatives have gotten themselves tangled up in this web because they don't understand that their own critique of big government rationing is a metaphor. Sometimes rationing really happens. During World War II, governments suffered from a lot of commodity shortages, and for the sake of equity chose to distribute the scarce commodities via rationing—hard caps on the quantity anyone is allowed to buy with his or her own money—rather than prices. Contemporary American cities often ration on-street parking. Meter rates are generally low, and resulting shortages are dealt with via rules limiting the maximum quantity of parking time you can purchase. This is real rationing, and it's very inefficient. In theory you could institute a strict licensing regime on health care services, but nobody's proposing to do so and there's certainly no fiscal policy need to do so. What's being proposed is to try to deploy evidence about the effectiveness of different treatments to limit what Medicare will pay for, leaving people free to pay for it themselves if they want to. Conservatives who don't like this idea chose to metaphorically label this "rationing" but it's no different from what they themselves are proposing to do. They just want to add a new layer of rent-seeking profiteers into the mix.

Cathie Black's Departure Is Almost Certainly Good News For New York City School Reform

Like Dana Goldstein it seems to me that Cathie Black leaving the New York City Department of Education is almost certainly good news:

It seemed self-evident that, politically, the best person for Mayor Bloomberg to appoint to be the face of his education agenda would be someone who could soothe anxieties around race, class, neighborhood autonomy, and instructional best practices. Cathie Black was, almost comically, the opposite of all that. A publishing executive with no personal or professional experience with any public schools school sytem–let alone with the incredibly complex New York City public school system–Black sent her own two children to private boarding school in Connecticut, and had attended parochial schools herself. As my friend Elizabeth Green just noted on WNYC, one of Black's first comments upon visiting New York City school buildings was that they seemed "clean."

Black's replacement, Dennis Walcott–currently Deputy Mayor for Education and Community Development–has a very different biography. He attended Queens public schools during the integration and community control struggles of the 1970s, so comes to the job with a deep appreciation of the difficult history of the New York City schools. A social worker, Walcott worked as a kindergarten teacher before pursuing a career in youth and anti-poverty advocacy, eventually serving as CEO of the New York Urban League.

The school reform movement, whose agenda I largely support, has a problematic tendency to at times get too caught in what its funders (typically rich finance guys or software barons) like to the exclusion of building support among the working class minorities who are the main constituency of public school systems. Personnel change to someone more appropriate can help the substantive agenda move forward. When Michelle Rhee ran DC Public Schools she had a bunch of good ideas and was also a publicity hungry loudmouth who became a polarizing figure in the city and beyond. Her unpopularity with African-American voters helped sink the mayor she worked for and risked spiking the entire substantive agenda. But fortunately, Mayor Vince Gray wound up replacing Rhee with Rhee's deputy, Kaya Henderson, a black former schoolteacher who has similar ideas but may be better able to put reform on a politically sustainable basis.

As an early-adopting blogger and professional political pundit I, personally, like hard-charging loudmouth jerks and think people like me have a role to play in the process of political change. It's just not necessarily the role of administrator for the long haul.

Life in the Colonies

Brian Beutler notes an abortion rider that hasn't gotten much play: "But there's one in there, too, which would prohibit the city of Washington, D.C., from using its own, non-federal funds to pay for abortions, beyond the accepted limits for the use of federal funds — rape, incest, or life of the mother."

That should tell you a lot about abortion proponents' willingness to leave abortion policy up to the states if Roe v Wade is overturned.

Conservatism I Can Believe In

The Florida right-wing is finally indulging some of my more conservative policy preferences:

A controversial bill that would deregulate 20 professions and industries passed the House on Thursday by a vote of 77 to 38. The bill ends oversight for everything from auctioneers and interior designers to hair braiders, intrastate movers, auto repair shops, telemarketers and charitable organizations. Opponents say HB 5005 is a threat to consumer protection.

This is right on. There's precious little evidence that this kind of registration and licensing achieves anything consumer protection-wise. Conservatives probably aren't interested in this, but I'd be happy to see just about any state beef up its spending on generic enforcement of laws against fraud. That's the right way to the threat of a bum auctioneer or auto repair shop. Also note that one of the good things about ongoing advances in information technology is that they allow these kind of markets to operate more efficiently. There are serious asymmetrical information problems with the auto repair industry that licensing regulations fail in practice to resolve. Things like website where people can review service providers, by contrast, actually help us advance somewhat on that front.

The Obamaite Origins of Ryanism

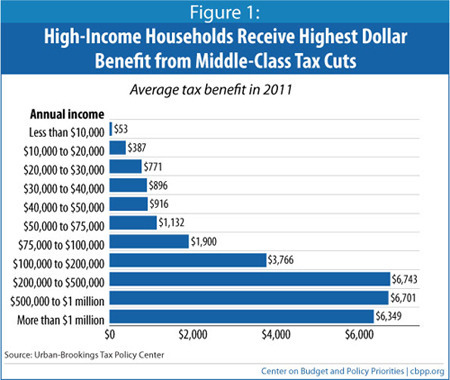

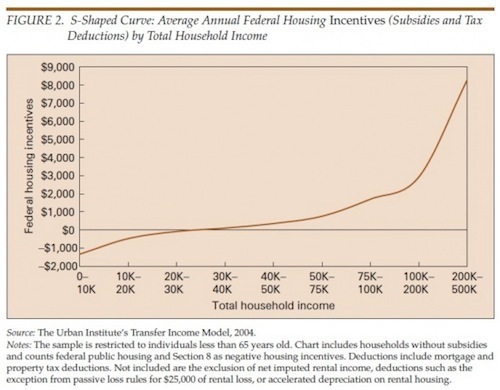

One way of making a point I've been trying to make for a while is that something along the lines of Paul Ryan's budget is eventually going to be made inevitable if progressives stay stuck on Barack Obama's pledge to not raise any tax revenue from any non-rich people. The problem with this isn't that there's no more capacity to tax the rich, it's that a lot of the best ways to tax the rich do require some taxation of the non-rich as well.

For a quick look at this, just take a gander at the distributive impact of the "middle class" Bush tax cuts that Obama is committed to extending:

Or look at our hideously regressive housing subsidies:

Rescinding either of those would be an economically efficient way of sticking it to the rich, but it's very difficult to make these measure economically efficient while completely sheltering the middle class from the impact. And that's even before you get into legislative trickier like last winter's stunt where congressional Republicans held the "middle class" tax cuts hostage to bonus rich people only tax cuts. Ultimately the only way to raise revenue is to be able to make the case that public services are worth paying money for. You can structure revenue measures to be distributively progressive, but you can't categorically promise that 100 percent of the burden will fall on the rich.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers