Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2361

April 9, 2011

The Economics Of Attention

One of the most important things about the health care and education segments of the economy is that part of what customers want is attention. Parents like the idea of small class sizes, and patients like the reassuring face-to-face presence of a doctor with a good bedside manner. But personal attention has the pretty special characteristic of being immune to productivity enhancements. This creates the following trilemma as economy-wide productivity rises:

— One: The wages of teachers and doctors can fall relative to average wages, because teachers and doctors aren't increasing their productivity as rapidly as the average worker.

— Two: Paying the salaries of teachers and doctors can account for an ever-growing share of national output, because the rest of our output is getting more efficient and teaching and treating isn't.

— Three: The amount of attention provided by teachers and doctors to students and patients can decline.

It's not that you need to pick one of those three things, but you can't pick zero of them. And it's not that three necessarily needs to mean declining educational and health outcomes. Attention is important to people, subjectively, but it's hardly the only thing that matters for learning and it's definitely not the only thing that matters for health. If doctors spend less time with their patients but are able to prescribe more effective drugs, that's a net benefit. And it's possible to increase reliance on less-trained kinds of medical professionals who are paid less than doctors but may still be competent to perform attention-paying functions. On instinct, though, people's preferences are for smaller classes, more face time with doctors, and more of a sense of personalization and customization. I still hear older people sometimes reminisce about the doctors of yore who'd pay house calls, hardly noticing that this inefficient use of medical professionals' time just reflects low economy-wide productivity.

I find that a frustratingly large share of discussions of these issues involves too much talk of dollars and cents and not enough qualitative talk along these lines. That allows people to avoid saying what they mean. Hold the growth of federal health spending to the rate of inflation? Sounds great! But what does it look like? If the bottom third of the income distribution stops being able to afford to see the doctor, that frees up more doctors' time to pay attention to richer people. So that's one possible answer. But if that's what you mean, that's what you should say. And if you think we need to increase the relative wages of teachers while further shrinking class sizes and sustain that policy over time, it'll mean steadily increasing taxes, no one-off increase will undue the Baumol Effect. That's one possible answer—America is lightly taxed compared to other rich countries—but you owe it to yourself at least to face up to that.

Debt Ceiling and Shutdown

Incidentally, I think the dynamics of a debt ceiling faceoff and the dynamics of an appropriations faceoff are quite different. That's because a lapsing of appropriations triggers a very specific set of occurrences. When appropriations lapse, it becomes illegal for the federal government to do anything not related to the "essential functions" of human and population security. The key issue here isn't that the government doesn't have money. If you're willing to work without pay temporarily, you're not allowed to work if you're deemed non-essential.

This is hugely disruptive and it's obviously very burdensome to people who rely on government services.

The debt limit is a different kind of thing. When the Treasury lacks authority to engage in new borrowing, all that means is that the Treasury lacks the authority to engage in new borrowing. Nothing else has to happen. Some money will still be flowing in, which means some money can continue to flow out. And the administration has some flexibility in how it handles this. What's more, the government can ask people to continue to do things in exchange for IOUs. Large defense contractors, for example, don't live on a paycheck to pacycheck basis. And if Robert Gates calls up an airplane manufacturer and says "look, we can't pay you this month but keep building the planes and we'll pay what we owe once the debt ceiling fight is resolved" the guys who build the planes are going to keep on building planes. There's no dramatic "hostage" moment, there's just a small-but-growing inconvenience for a large number of people who rely in part on government checks to make a living. That all happens well before the federal government would be forced into a default scenario where it can't pay off bondholders.

How that plays out in practice seems to me difficult to predict, but it's not the same as shutdown dynamics.

Digital Currency And The Zero Lower Bound

Once upon a time, "money" referred to coins made out of precious metals. Then circulation began to primarily consist of pieces of paper that were redeemable in exchange for fixed quantities of precious metals. But more recently we've shifted to a system of fiat money—a paper dollar is exchangeable for some euro coins or for a little mark on your bank account saying that you have a dollar in there. And in the modern day the vast majority of the money is electronic, rather than physical currency. CAP doesn't ever hand me an envelop full of bills, they directly deposit the money in my bank account. And the majority of that money flows out again in electronic form—Bank of America takes some to pay my mortgage, Chase takes some to pay my credit card bills, Comcast and Pepco take some to pay my utilities, etc. The physical cash is just a small residual element.

But it continues to play an important role in the macroeconomy. That's because it's the main reason for the existence of a "zero lower bound" on interest rates.

The general idea of interest rates is that to the extent that they're lower, people will be less interested in holding currency in the bank and more interested in obtaining some goods, services, or investments. But if our bank started paying a negative interest rate (i.e., charging you to store money) this mechanism would break down. You'd want to largely "invest" in shoeboxes full of pieces of paper with Ulysses Grant's face on them. But this is purely an artifact of the existence of the paper money residuum. If we moved to a system in which all transactions are done electronically (debit cards, credit cards, direct deposit, electronic transfer, etc.) then going from 1 percent interest rate to -1 percent interest rate would be no different from going from 7 percent interest rate to 5 percent interest rate. The gains for macroeconomic stabilization (and tax enforcement) could be huge. And it's only a matter of time before someone tries it. The question is who'll go first? My bet would be on Singapore, South Korea, or perhaps Sweden.

Our Unconstitutional Constitution

SK writes: "Do you know of any legal path to getting rid of or disempowering the Senate that would not require Senate approval?"

It all depends on what you mean by "legal" but the short answer is "no." The longer answer is just to observe that the existing United States Constitution was adopted by means that were, at the time, illegal. Elites felt that the Articles of Confederation were inadequate to resolving the problems of the country, so elites gathered to write a new constitution that contained a ratification procedure at odds with what's spelled out in the Articles. Then along they went seeking ratification by various states and when they had the number the said was necessary, they declared victory and pushed ahead, installing victorious General George Washington as the new head of state and head of government.

At some point in the future if there's some crisis, you could imagine something like that happened again. The current constitution of France has a somewhat similar origin in a political crisis followed by an extra-constitutional moment and then a referendum. These things happen, though not frequently.

The Success Of Hostage-Taking Highlights The Importance of Elections

Details on the appropriations deal are still hard to come by, but you don't need the details to know that substantial short-term cuts in domestic discretionary spending will hurt the poor while harming macroeconomic performance. The problem with not agreeing to the deal, of course, is that a government shutdown would also hurt the poor while harming macroeconomic performance. If you genuinely don't care about the interests of poor people and stand to benefit electorally from weak economic growth, this gives you a very strong hand to play as a hostage taker. And John Boehner is willing to play that hand.

I hope people remember this year next time large Democratic majorities produce an inadequate stimulus bill, a not-good-enough health reform bill, a somewhat weak financial regulation bill, and fail to deliver on their promises for immigration and the environment. It's easy in a time like that to get cynical and dismissive about the whole thing. But there's actually a huge difference between moving forward at a slower-than-ideal pace and scrambling to reduce the pace at which you move backwards. Now we're moving backwards.

April 8, 2011

Endgame

Gonna shut you down:

— The Purple Health Plan seems like a relatively small variant of the new Affordable Care Act status quo.

— If you live in New York City you can come see me speak on a panel tomorrow afternoon or (more fun) see me drink at the afterparty later.

— Paul Ryan's bad infrastructure ideas.

— Mike Huckabee says the GOP should cut a deal.

— Profiles in cowardice.

Beach Boys, "Shut Down".

The Affordable Care Act Contains Plans To Reduce The Growth In Health Care Costs

The debate over the budgetary impact of the Affordable Care Act quickly became polarized between Democrats, who said that Congress should rely on the Congressional Budget Office's scoring of the legislation, and critics who for reasons that were never made clear to me said it made sense to initiate a one-time exception to the rule and assert without argument that the CBO is wrong. Lost in this argument were assertions from the other side that the CBO was being too pessimistic. But there's a decent argument that they were.

The basic shape of things is that the CBO was only willing to score crude quantitative means of reducing health care costs. If you cut a spending formula, the CBO will score that as a saving. If you tax certain kinds of insurance plans, the CBO will score a reduction in demand for those plans. But the CBO refused the score the idea that certain incentive programs and pilot initiatives would actually drive more efficient organization of health care. That, however, is a scoring rule they adopted, it's not a claim that it's impossible to provide health care more efficiently. And you can't deny that there are an awful lot of initiatives tucked here and there in the Affordable Care Act that are intended to do this. The CBO didn't want to score them, but they are in there, and they were put in there by smart people who believe they'll work.

Some of those smart people—David M. Cutler, Karen Davis, and Kristof Stremikis—did a paper on this for CAP back in May of 2010. Here's a taste:

Other estimates, however, suggest that an aggressive approach to health care modernization could result in significantly greater cost reductions. Beeuwkes-Buntin and Cutler estimated a 1.5-percentage-point reduction in cost increases annually from significant health care reform, or more than $700 billion in the 10-year window. These savings would come from two primary sources. First, administrative expenses incurred by provider groups would decline as electronic medical records, and incentives to use them appropriately, are widely disseminated. The potential for administrative savings has been stressed by both provider groups and insurers, and they are distinct from the reduction in insurance administration noted above. Second, reform would lead to fewer and less-costly acute care episodes. Potentially substantial savings could be had by preventing certain illnesses from recurring through better coordination of care and by rationalizing what is done when a person becomes sick by bundling payments, paying more for quality care, and sharing savings with accountable provider organizations.

Similarly, Hussey, Eibner, Ridgely et al. estimate that savings of more than 10 percent are possible, largely from payment reforms like bundled-payment systems. Realizing these savings over a decade implies cost reductions of nearly 1.5 percentage points annually. A more conservative mid-range set of assumptions suggests that such reforms could reduce growth in national health expenditures by about one percentage point per year.

Now maybe you think Cutler, et. al. are wrong about this. Indeed, maybe time will show that they are wrong. But it's mistaken to argue that progressives have no vision for further controlling the growth in health care costs. The belief is that some of this stuff will pan out. And the hope is that once we see what's panning out, we'll have a better idea of how to build on the successes. That's the plan.

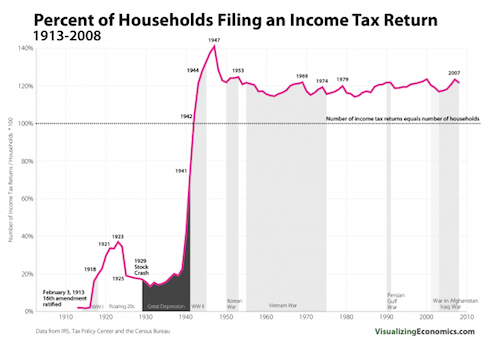

The Income Tax: Brought To You By World War II

Very interesting chart from Catherine Mulbrandon shows us how the income tax went from being a marginal to a mass phenomenon:

Income tax has a certain logic as a wartime measure, especially given the super-full employment conditions that pertained at the time. Over the long term, however, I think people will come around to the future that a consumption tax with a progressive rate structure makes a lot more sense when we're not amidst a total war.

Freedom From Fear of Sluggish Economic Growth

Corey Robin makes the case that progressives need to reclaim the language of freedom. The argument may be correct, but you should always beware people carting arguments that attribute FDR's stunning electoral success in 1936 to elements of his rhetoric:

In forging his realignment, Roosevelt was careful to identify the enemy not as a political party but an economic aristocracy. Throughout the 1936 campaign, he barely mentioned Alf Landon. Instead, he denounced the Liberty League and the businessmen it represented. Realignments in America are like that: Jackson railed against the Bank; the Republicans ran against the slaveocracy; Reagan campaigned against the liberal elite. Part of this is strategic: it's easier to peel away voters from the opposition if you can show that it is not their party you oppose but the interests it represents, which are not theirs. But part of it is substantive, reflecting a conviction that the task at hand is not simply to defeat a party or win an election but to free men and women from a malignant social form.

Just keep in mind what was happening to the economy:

Any politician would look like a genius under those circumstances. And you see the same with Ronald Reagan's landslide win in 1984.

Fragmented Health Care System Makes Explicit Discussion of Tradeoffs Difficult

Kevin Drum's observation that "[i] a national healthcare system, taxpayers who are footing the bill have to make decisions continuously about how much they're willing to pay for healthcare" prompts a thought from me that the generational transfer element of Medicare makes it difficult to engage in these tradeoff calculations.

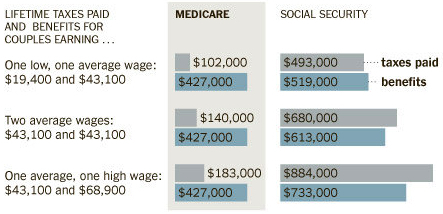

The way this works, recall, is that Medicare is a universal single-payer health insurance scheme for retired people. And it's financed through payroll and income taxes. Consequently, there's virtually no overlap between people who are paying taxes to finance Medicare and people who are benefiting from Medicare. Worse, people suffer from the illusion that Medicare is something they've already "paid for" via their payroll taxes in their working years. For Social Security this is approximately true, but for Medicare it's not even close:

This is why Paul Ryan's Medicare proposal features an arbitrary ten year delay before it's phased in.

A more typical system would feature universal coverage starting at age zero and a large chunk of the financing would come from a Value Added Tax, which people pay whether they're working or not. There's still always an element of inter-generational transfer since old people consume more health care services on average. But there's less insulation. If you cut health care spending right now, then right now the very same people will be able to pay lower taxes. Alternatively if you want to boost health spending right now, then right now the very same people will have to pay higher taxes. This hardly guarantees wise choices, but it frames what the choices are correctly.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers