Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2362

April 8, 2011

Effect and Cause

GOP To Shut Down Government Over Mythical United Nations Financing of Abortions

Planned Parenthood is getting all the attention because Americans know what it is and use their services, but the Planned Parenthood rider isn't the only plank in the right's war on reproductive health services that's holding up negotiations. Republicans, led by Chris Smith of New Jersey, also have a rider about the United Nations Population Fund, which they don't like because it funds abortion even though it doesn't fund abortion:

I spoke with Sarah Craven of the United Nations Population Fund moments ago. She, once again, reiterated that UNFPA does not fund abortions. After all, she said, UNFPA is a part of the UN–and there are several UN members states in which abortion is still illegal. Beyond that, UNFPA's steering document specifically excludes abortion as a method of family planning under UNFPA's mandate. If that were not enough to convince you that U.S. funds to UNFPA does not go toward promoting or conducting abortion, the U.S. Congress has passed several pieces of legislation since the 1970s specifically stipulating that no U.S. funds can in anyway support abortion overseas.

Still, several members of Congress–most notably Chris Smith of New Jersey–are somehow convinced that UNFPA promotes abortion. Specifically, they are concerned that UNFPA abets China's one child policy. This is false, but you don't have to take my word for it. In 2001, the Bush White House sent a fact finding team to investigate UNFPA in China and found, "no evidence that UNFPA has supported or participated in the management of a programme of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization in China."

This won't get people as riled up, but realistically the harm done to public health here is probably bigger than with Planned Parenthood since UNFPA's work is concentrated in places that are so much poorer.

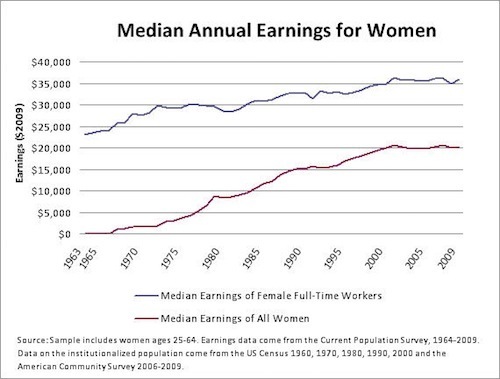

Median Wage Stagnation Catches Up With Women

I think a neglected element of the politics of wage stagnation in the United States is that for most of the stagnation period women's wages have been rising a lot. But Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney of the Brookings Institute report that the party's over:

The recession, obviously, is unlikely to improve this trend.

If Government Shutdown Halts DC Parking Enforcement, That'll Be Bad Just Like The Rest

Something about automobile parking seems to drive otherwise good people bonkers. For example, James Fallows amidst a sensible post about a government shutdown echoes a desire I've heard from a lot of people for DC to stop enforcing parking laws:

I have relatives who live in Saudi Arabia. A large group of high schoolers, including their son, from an international school in Riyadh is excited about their upcoming spring trip to Washington, which begins this weekend. For many it will be their first view of the United States. And they will find: Smithsonian museums closed. National Zoo closed. DC trash collectors furloughed. No parking-law enforcement (well, there's a bright side). The kinds of things one associates with … the third world.

The case for enforcing parking laws is exactly the same as the case for enforcing all laws. Any individual driver might reasonably prefer a world in which he can get away with breaking the rules, but if you stop enforcing the rules then everyone is going to break them. That doesn't ultimately help anyone. It seems to me that everyone would ultimately gain a lot of relief if we just faced up to the fact that space in crowded urban centers is finite and valuable, and therefore ought to be fairly expensive. Then we'd have less effort to allocate via rationing, and less temptation to break the rationing rules.

Undergraduate Economics Education

Brad DeLong offers his thoughts on undergraduate economics education in America:

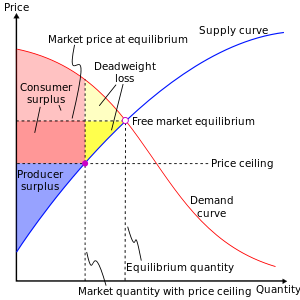

The problems with the undergraduate curriculum qua curriculum seem to me to be largely problems with the history and context of the discipline–rather, the absence of same. Otherwise, the trot through market equilibrium, market optimality, market failure, and simple macroeconomics seems to work well. I might wish for more behavioral psychology in the market equilibrium part and a much better look at government failure in the market failure part, but those may come. I do think that warning labels should inform right-wing students that economics will encourage their bad intellectual habits just as labels should inform left-wing students that sociology will encourage theirs. The mix of words, algebraic equations, and analytic-geometric graphs and the requirement that students move back and forth among all three seems to me to turn a subject that ought to be conceptually rather easy into one that is, for the bulk of American students, relatively difficult.

I'm not so complacent about this. It seems to me that conventional basic undergraduate economics suffers from a kind of wrongheaded and somewhat lazy choice of examples. Obviously it's difficult to generalize, but my impression is that the examples of price distorting regulations are always rent control and the minimum wage rather than bans on accessory dwellings or software patents. The overall impression given is that according to economists the main source of inefficient economic regulation is well-meaning but misguided efforts by progressive activists to help poor people. The main impact of this is to cause well-meaning progressive activists to tune out microeconomics and cause rightwingers to become more self-righteous.

But the political economy of that model doesn't make any sense. Why would it be the case that the primary source of government intervention into the economy is the political clout of well-intentioned idealistic advocates for the poor? A much more typical example—and one that should resonate with college students—would be something like well-heeled homeowners in college-adjacent neighborhoods seeking regulatory barriers to student housing. Similarly, a nice explanation of the mix of social loss and private gain that would be involved in perfect enforcement of the laws against bittorrenting episodes of your favorite TV show would be demographically appropriate and illustrate a more realistic vision of political economy. This would go along well with DeLong's point about history and context, situating the field closer to its classical liberal origins as a scourge of privilege rather than a kind of weird way of sneering at America's barely-extant private sector labor unions.

The Heritage Foundation's Fuzzy Math

Annie Lowrey delves deeper into the Heritage Foundation's macroeconomic forecasting and finds it a bit fishy:

The model derives the unemployment rate from two variables: a wage-price variable (essentially, how much workers cost) and the full-employment unemployment rate (essentially, the lowest the unemployment rate can get without spurring inflation). Beach says he felt that latter variable had been set too low. He set it higher, re-ran the whole shebang, and came out with new, higher unemployment rates—with no impact on the rest of the model. Total employment, public employment, and private employment were never affected, he says.

This doesn't seem to be how anyone else does it, possibly because it doesn't seem to me to make any sense.

It's worth trying to think about the track record of this method. It's not good. Recall their forecast that George W Bush's tax policies would launch an unprecedented labor market boom:

Didn't happen.

Podcasting the Fed

I'm the guest on this week's edition of the acclaimed Chris Hayes podcast "The Breakdown." We're talking federal reserve and monetary policy.

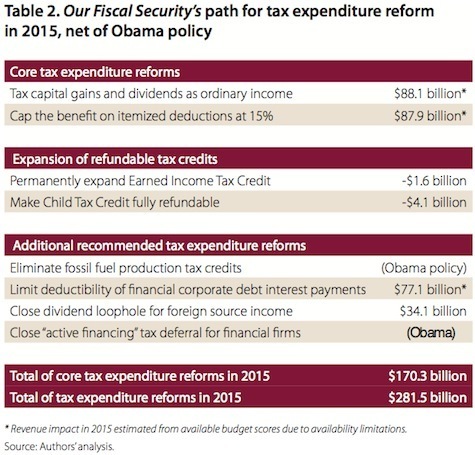

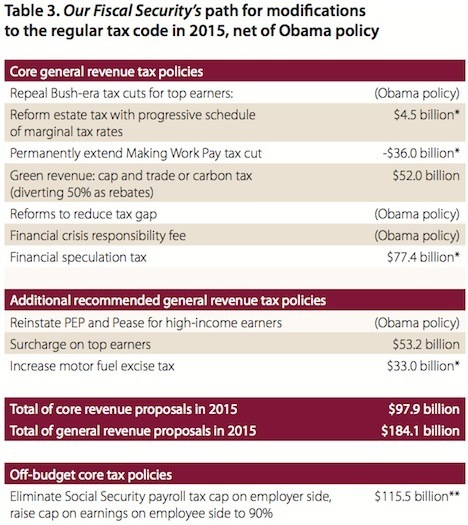

A Rigorous Progressive Budget

A friend reminded me that folks looking for a rigorous progressive framing of a long-term budget should check out the Our Fiscal Security report done last year by Demos, EPI, and the Century Foundation. On the spending side, the key ideas here are defense cuts, targeted increases in public investment (mostly in the fields of education and infrastructure), and an expansion of technocratic health care cost controls. On the tax side, this is what it looks like:

And:

I'm not sure that's exactly what I would do, and I believe my colleagues at CAP are working on some ideas of their own, but it's a good look at the basic shape of what a progressive dream budget ought to look like.

Government Shutdown Will Disrupt Student Loans

The federal government's has an arms length role in education, so the overall impact of a federal shutdown on schools will be limited. One exception, Michele McNeil explains, has to do with student loans:

In addition, the department said today that although most student federal aid programs would not be impacted by a shutdown, colleges and universities would not be able to draw down and disburse to students any campus-based program awards, such as work-study or the Federal Perkins Loan Program. The impact on the $951 million work-study program would affect about 590,000 students in approximately 3,400 participating institutions. Perkins affects about 673,000 students in some 1,600 participating institutions.

A lot of people seem to have a hazy sense that "the government" is something that has nothing to do with their lives, but if House Republicans prove unwilling to back down on some of these policy riders a bunch of folks are about to find out otherwise.

Doing Versus Saying

(cc photo by John Pannell)

Initially I was puzzled by Stephanie Clifford's article about how retailers are finding they can boost sales by packing more crap into the aisles. Maybe I'm a weirdo, I thought, but I greatly prefer to shop in sparser places. It turns out, however, that I'm not a weirdo and people are just huge hypocrites about this stuff:

"They loved the experience," William S. Simon, the chief executive of Wal-Mart's United States division, said at a recent conference. "They just bought less. And that generally is not a good long-term strategy."

So after remodeling a large percentage of its stores, Wal-Mart is now re-remodeling them, adding back inventory, plopping stacks of stuff into aisles and stacking shelves with a dizzying array of merchandise.

As it turns out, the messier and more confusing a store looks, the better the deals it projects.

"Historically, the more a store is packed, the more people think of it as value — just as when you walk into a store and there are fewer things on the floor, you tend to think they're expensive," said Paco Underhill, founder and chief executive of Envirosell, who studies shopper behavior.

There's a related and more serious issue, it seems to me, in the health care market. People naturally say that they want good health outcomes at a reasonable price, but there's precious little evidence from action that this is really what folks are after. Lawsuits are more determined by bedside manner than by health results, people want to have a sense of agency and control, people want to demonstrate care and concern for loved ones, etc.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers