Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2318

May 10, 2011

Hours Worked And Family Policy

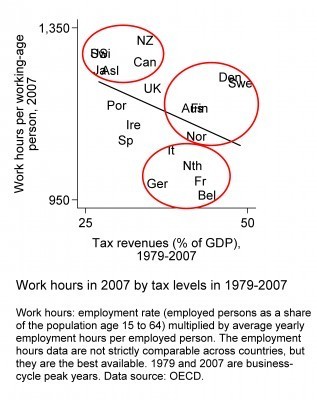

Here's a chart from Lane Kenworthy:

His interpretation is that this is mostly not about taxes, but about family policy:

One group, in the lower-right corner, includes Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, France, and Belgium. These countries, along with Austria, have several features that might contribute to low work hours. One is strong unions. Organized labor has been the principal force pushing for a shorter work week, more holiday and vacation time, and earlier retirement. These nations also have been characterized by a preference for traditional family roles: breadwinner husband, homemaker wife. This preference, often associated with Catholicism and "Christian Democratic" political parties, is likely to influence women's employment and work hours. It is manifested in lengthy paid maternity leaves, lack of government support for child care, income tax structures that discourage second earners within households, and practices such as German school days ending at lunch time and French schools being closed on Wednesday afternoons. These countries also fund their social insurance programs via heavy payroll taxes, the kind most likely to discourage employment growth.

A second group consists of the four Nordic nations: Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway. These countries too have strong unions. But they also have had electorally successful social democratic parties, which have tended to promote high employment. Denmark and Sweden, in particular, have been at the forefront in use of active labor market programs to help get young or displaced persons into jobs, public employment to fill gaps in the private labor market, and government support for child care and preschool to facilitate women's employment.

One way to characterize this, perhaps, is in terms of which kinds of political parties dominate on the right. In the hard working countries, the main right-of-center party defines itself as "liberal" whereas in the barely working countries the main right-of-center party doesn't. The Netherlands may be an interesting test case here since traditionally the Christian Democrats have been the dominant right-of-center force but in the most recent election they lost that status to a liberal party. Will that mean an upsurge in policies designed to encourage people to work more?

My Superhero Is Black

By Alyssa Rosenberg

Gene Demby has a true barnburner of a piece in this month's American Prospect breaking down America's fears of a black superhero. He writes:

A purple-skinned alien hurtles across the cosmos, bearing a ring that grants its wearer unimaginable power. The alien is mortally wounded, and the ring is seeking its next wearer — the Green Lantern, Earth's champion — by finding the planet's most courageous inhabitant. In a world with billions of people, what are the chances that the ring's next owner is a white American dude?Pretty high, apparently…In the early days, whiteness was so pervasive in comics that it could actually span the universe: a Kryptonian Superman could crash-land in Kansas and pass as an ordinary white farm boy.

You really should read the whole thing. It's a critical reminder of how resistant our popular culture can be to images of black power. And if we want different kinds of superhero stories, focusing on different heroes, whether they're protecting their countries from colonization, trying to balance their duties as crimefighters with their day job as Secretary of Education, or working in superheroically under-served communities (not to mention pioneering new areas of legal practice—I want my She-Hulk movie), is the quickest way to find ones worth telling. There are only so many ways to portray yet another white dude trying to come to terms with his newfound specialness.

The House Republican Budget Privatizes Medicare, It Doesn't Means-Test It

At House Minority Whip Steny Hoyer's weekly briefing, Brian Beutler asked him about the idea of means-testing Medicare and Hoyer said he's open to it, but he can't really say "until we look at specific proposals."

That seems correct to me, but part of the importance of specifics is underscored by Speaker John Boehner's earlier remarks about means-testing wherein he described a very radical agenda that would totally eliminate Medicare as if it's a fee increase on rich seniors:

"Pete [Peterson], I love you to death, but I don't think the taxpayers ought to be paying your Medicare premium. And under Paul Ryan's plan, what it says is, let's allow the American people to decide which health care plan fits their needs. And if you're middle-income, lower income, we are going to pay, just like we do today, for the cost of those premiums. But for people of means, there's no reason why we should subsidize Pete Peterson's premium. I'm sorry. He ought to pay the full cost of his premium to be in Medicare."

The idea that someone as rich as Peterson ought to pay the full cost of his Medicare premium is worth considering (I have some affection for this idea). But "Paul Ryan's plan"—which is also Boehner's plan since the Boehner-led House voted for it—wouldn't lead to Peterson paying the full cost of his Medicare premium. For one thing, Peterson was born in 1926 and part of the political sales job of the plan is to say that people Peterson's age won't be affected at all by the cuts and privatization. And then of course there's the small matter of the privatization!

For the people who would be directly impacted by the House GOP plan, there would be no more Medicare premiums for anyone to pay. Anyone under the age of 55 would be permanently ineligible for the publicly administered single-payer health care plan that we currently call "Medicare" and that presumably would continue to be called "Medicare" for folks like Peterson and Boehner who'd be eligible for it. What people my age would get would be a partial rebate of the private sector health insurance we go buy on the individual market. The value of the rebate would steadily diminish over time, and higher-income seniors would get lower-value rebates than lower-income seniors. Peterson and Boehner, meanwhile, would continue paying the exact same premium schedule but over time would find that more and more health care providers refuse to treat Medicare patients.

What It Looks Like When You Run Out Of Money

This short Planet Money item on Iceland running out of foreign currency is excellent, both on its own term and also because it's a useful illustration of exactly why the US isn't "going broke":

The problem the hedge fund guys had spotted was in fact, the joke that John Cleese commercial: Iceland is a very small country. It's the smallest in the world to have its own currency. And it had borrowed huge amounts of foreign currency. Normally that wasn't a problem. Icelandic banks could always change their domestic currency, the krona, for dollars or euros on the world market. But now the world was worried. And no one wanted krona. In a bigger country, banks might get some foreign currency from their own central bank. But Iceland's central bank also ran out of dollars and euros.

"The central bank used all it had in a desperate attempt to save one of the banks," the economist Gylfi Magnússon says. "But that only kept the bank afloat for another couple of days."

The point here is that while we frequently use words like "money" and "yen" interchangeably, these are different things. The krona is a kind of money, but while Iceland can't run out of krona it can run out of dollars and yen and euros. And since Iceland is tiny this is a huge problem. Small countries can't host large banks.

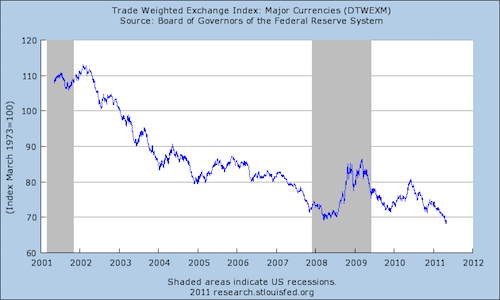

The United States is very different. Global demand for dollars appears to be in some kind of longish term decline related to the rise of China's export machine, but in periods of crisis demand for dollars goes up:

Lucky for us! That's why it's nice to be a big country with a stable political system and deep and liquid financial markets.

In Washington, You Don't Need To Know Anything About Policy To Be a Senator Or Chair Important Commissions

Here's an important fact about the United States of America. Since 1940, advances in prenatal, neonatal, and pediatric medicine have massively reduced early in life deaths. This is common sense. When I was a kid, I was vaccinated against all sorts of diseases that we didn't have vaccines for 70 years ago. I also wasn't vaccinated against smallpox because smallpox doesn't exist. When I got strep throat, I was treated with antibiotics. When that didn't work one time and the strep developed into scarlet fever, I was treated with more and different antibiotics. So since lots of little kids used to die of mumps and rubella and such, a lot of the increase in life expectancy over the past 70 years has been driven by these kind of things.

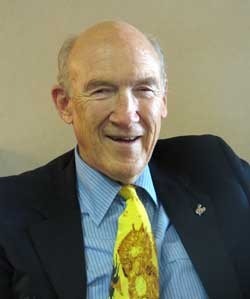

Ryan Grimm knows this, but apparently Alan Simpson doesn't:

Simpson argued that Social Security was originally intended more as a welfare program.

"It was never intended as a retirement program. It was set up in '37 and '38 to take care of people who were in distress — ditch diggers, wage earners — it was to give them 43 percent of the replacement rate of their wages. The [life expectancy] was 63. That's why they set retirement age at 65" for Social Security, he said. [...]

HuffPost suggested to Simpson during a telephone interview that his claim about life expectancy was misleading because his data include people who died in childhood of diseases that are now largely preventable. Incorporating such early deaths skews the average life expectancy number downward, making it appear as if people live dramatically longer today than they did half a century ago. According to the Social Security Administration's actuaries, women who lived to 65 in 1940 had a life expectancy of 79.7 years and men were expected to live 77.7 years.

"If that is the case — and I don't think it is — then that means they put in peanuts," said Simpson.

Later in the interview, Simpson reveals that doesn't what life expectancy even means: "If you're telling me that a guy who got to be 65 in 1940 — that all of them lived to be 77 — that is just not correct." And of course it's not correct. Plenty of people turned 65 then died the next year. But on average, a 65 year-old man in 1940 could expect to live 12-13 more years. But the really striking moment is when Simpson says this to Grimm:

"This is the first time, the first time — and Erskine [Bowles, the deficit commission co-chair,] and I have been talking for a year and many months — that anyone's going to sit around and play with statistics like this."

That's right, according to former Senator Alan Simpson not only did he not familiarize himself with the relevant life expectancy data during his many years in the Senate, he's never once brought it up during his months of work on a commission specifically charged with re-evaluating America's retirement programs. And this, in turn, tells you a lot about how Washington works. There are tons of people in this town who know lots of things about public policy. But possessing this knowledge isn't considered an important qualification for these kind of jobs. Simpson is old, and he used to be an influential Senator, and since he was pro-choice he's also "moderate." That's all the qualification you need. Actual knowledge isn't important.

The Pernicious Politicization Of The Judiciary In The Face of Affordable Care Act Litigation

The computer that assigns judges to 4th Circuit cases today drew a panel of three Democrats to hear the appeal over the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, leading conservative reporter Philip Klein to immediately tweet that the bill's constitutionality will be upheld.

And of course he's right. But it tells you something about the nature of the litigation that this is all the information you need to know about the case. Lawyers are still going to go through the motions of arguing it, of course, but the Solicitor General could just toss off a randomly chosen quotation from The Federalist and he'd still win the case.

Of course politics is nothing new to constitutional law, but it's worth noting that there's a very particular kind of politics at play here. That's because as best I know absolutely nobody denies that it would be constitutional for Congress to implement a larger tax increase than is contemplated by the Affordable Care Act and then offer "health insurance vouchers" for people to buy insurance on regulated exchanges. That would be the exact same policy as the individual mandate, but wouldn't raise the pseudo-issue of "regulating inactivity" that conservatives are pretending to believe renders the ACA unconstitutional. This means that unlike it something like constitutional disputes over abortion or the regulation of pornography or the criminalization of sodomy we're actually not witnessing an ideologically driven disagreement about the fundamental nature of individual liberty. What we're witnessing is legislative gridlock. Everyone knows that the coalition behind the Affordable Care Act no longer has a majority in congress, while the coalition for repealing the Affordable Care Act also lacks a majority, so that even though it would be perfectly constitutional for congress to respond to an adverse judicial ruling by passing a slightly different version of the bill this won't happen in practice because the votes aren't there.

So while I'm not one to clutch my pearls at the revelation that there's politics happening in my judicial branch, it's worth noting that the particular kind of politics being practiced here is unusually lowbrow. It's a kind of partisan intervention into an ongoing legislative debate.

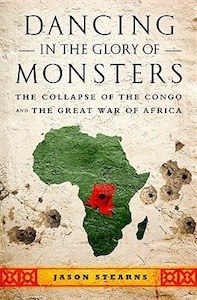

Dancing In The Glory of Monsters

I asked folks for recommendations about a book to read on the wars in Congo, and basically everyone told me to read Jason Stearns' new Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa. And it is, indeed, a tremendous book. This is a very complicated, largely unfamiliar subject that's basically off the radar of the American media and he's managed to produce a genuinely readable and engrossing account. To the extent that it's possible to breeze through a book about a years-long bloody civil war I breezed right through it. Stearns' central conceit, I would say, is an effort to sort of "normalize" discourse about the issue. Many important historical events have involved bloody military conflict and bloody military conflict often features atrocities. But when we talk about Napoleon or the 30 Years' War or whatever else we typically frame these events as important high-stakes political conflicts and not just series of atrocities.

Near the end he critiques some of the Congo-related advocacy efforts in a way that I think reveals his project:

These advocacy efforts have also, however, had unintended effects. They reinforce the impression that the Congo is filled with wanton savages, crazed by power and greed. This view, by focusing on the utter horror of the violence, distracts from the politics that gave rise to the conflict and from the reasons behind the bloodshed. If all we see is black men raping and killing in the most outlandish ways imaginable, we might find it hard to believe that there is any logic to this conflict. We are returned to Joseph Conrad's notion that the Congo takes you to the heart of darkness, an inscrutable and unimprovable mess. If we want to change the political dynamics in the country, we have above all to understand the conflict on its own terms. That starts with understanding how political power is managed.

In a slightly refreshing way, this is the only mention of Heart Of Darkness that occurs in the book, a clear contrast with Michela Wrong's also excellent In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu's Congo which directly highlights the Conradian madness element

Interesting reviews here, here, and brief recommendation here. Stearns' blog is here.

'30 Rock's' 'Eat, Pray, Love' Problem

By Alyssa Rosenberg

I've been struggling for a long time to crystalize my growing frustrations with 30 Rock, a show that had a nigh-perfect second season and has never consistently achieved the same comedic heights again. Is it the breakdown of the show that brought all the characters together? Jack Donaghy's parade of no-act honeys (Elizabeth Banks exempted, of course)? The fact that Liz Lemon gets written like she's ugly, or spectacularly awkward, or dumb? But over this weekend, when Elizabeth Gilbert announced that she wouldn't be speaking publicly about her insanely successful memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, anymore, another explanation occurred to me. For a brief, refreshing moment, Liz Lemon was the anti-Liz Gilbert, and 30 Rock was a rebuke to an ethic of self-care and excessive self-regard, preaching a fairly effective gospel of salvation through work instead. Watching the show abandon that argument to become the endless ugly-duckling half of a makeover movie has been exhausting and depressing.

When 30 Rock started, Liz Lemon was a mess, but an interesting one. She'd clawed her way up the comedy ladder and created the show she'd always dreamed of. When Jack Donaghy comes crashing through her dead boss's door and into Liz's life, she's annoyed because he insists on fixing something that she thinks isn't broken. But even as Jack upset Liz's show in the name of boosting the already-okay ratings, he offered her something kind of radical: a sense of how to fix her life by embracing her job, rather than through a radical physical or spiritual renovation.

In "Rosemary's Baby," the show leavens the hilarious awfulness of Carrie Fisher as crazed embodiment of Liz's future with a moment of genuine closeness between Liz and Jack, who promises to help her figure out her finances. When Jack plans to promote Liz in "Succession," the episode makes clear that the metrics for corporate success are absurd—not the idea that Liz could meet them. Jack is the person who forces Liz to stand up for herself at work and at home, with Tracy and with Dennis, even if it's with only mixed success. His insistence that Liz can learn and earn the things at work that she needs to build a happier, more complete life for herself has always showed a respect for Liz's workaholism that I appreciate.

And Liz actually meet a lot of terrific guys through her job, men who are attracted to her in an environment where she's competent and in control. No matter how those relationships ended, the guys she hooks up with through office connections—funny accountant Floyd, coffee cutie Jamie, actor Danny—generally stack up better than the guys she meets outside the office—Beeper King Dennis, insurance agent Wesley, dim diva Drew, and though this may be a controversial opinion, weirdly neurotic pilot Carol.* Her experience, and Jack's connection between Liz's personal and professional behavior, are a rebuke to a million working-girl-needs-to-make-time-for-love romcoms.

Lots of women have found the Gilbertian fantasy of flight and spiritual renewal inspiring, enough to turn her once-unusual journey into an industry. The appeal of a clean start is understandable, but 30 Rock's early insistence that Liz can become complete within the contours of her life is more affirming than the idea that the best way to find happiness is to flee the country and your old self. Unfortunately, the show's essentially abandoned that early optimism, its counternarrative about how women can find happiness. While she started out as a competent if unbalanced figure, the 30 Rock now treats Liz as if she's so ridiculous that deciding to mentor her is the decision that's derailed Jack's, life:

And it's not just that 30 Rock has backed off from the idea that Liz is a talented person who could rebuild her life through her work. The show's backed off from the idea that Liz can transform her own life through her job and has gotten more aggressive about mocking Liz for being bad at self-improvement outside of it. When Liz tries to quit eating junk food, she ends up with video of herself sleep-eating. She's never even gotten around to reading her copy of The Secret. She can't vacation in the Hamptons, fulfilling her dreams of hanging out with Ina Garten and learning Spanish (though to be fair, Liz's failed vacation is mostly the fault of Tracy-as-deus-ex-machina). This season, the show even shouted out the movie adaptation of Eat Pray Love by suggesting that Liz's perfect man would make fun of it—but said perfect man is actually an escort hired to help Liz believe in love again by sweeping her off her feet Liz-Gilbert-in-Bali style. It's even more depressing to watch her decide to cling to that flimsy fantasy than it is to see her outline her plans for spinsterhood, to watch Liz Lemon surrender to being a shadow of Liz Gilbert.

*There are exceptions, of course: Liz meets the World's Dullest Man, Steven Black, at a TGS after-party, and ends up dating Stuart, played by Peter Dinklage, after running into him on the street. But on the whole, the point holds, I think.

Better Rail Service Coming To The Part Of The Country That Values Good Rail Service

I'm glad to see that the absurd culture war over the Obama administration's relatively minor high-speed rail funding initiative has reached its logical conclusion, a healthy chunk of the money Governor Rick Scott doesn't want for Florida is going instead for track improvements in the Northeast where, as Kate Sheppard tells us, elected officials are cheering.

That sounds great to me. There's a strong case for more investment in passenger rail in the United States. And there's a strong case for federal involvement in that investment. And there's a case for doing it places other than the northeast. But passenger rail is necessarily a primarily regional kind of thing, and it needs to be in some sense led and initiated by people who welcome it. California seems to have a mass of voters and elected officials who want a regional passenger rail corridor and the kind of development patterns that entails. I think that if elected officials in Texas and Florida were smart, they'd also want that. But it seems like they don't. Here in the northeast we have a lot of rail-focused development patterns and we have a pretty robust passenger rail network. But Amtrak's Northeast Corridor service is sort of laughably primitive compared to a major corridor in Europe or Asia, so upgrades are welcome. I'd also be very interested in new projects that build on the existing Northeast Corridor—better service from DC down to Richmond, and from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia and DC, possibly Boston to Portland.

The conservative governors who've rejected HSR funding are, I think, making a mistake for their states. But their fanaticism is sort of doing the country a favor. The worst possible outcome would be for regional political elites who don't actually want rail infrastructure to say "yes" anyway for the short-term fiscal boost and then squander it. Intercity transportation investments only work if there's followup work on intracity transportation and land use.

Thirty Years Of Inflation History

Just a quick reminder:

I think Reagan had this right. Inflation that averages around four percent is consistent with robust growth and minimizes the risk that the nominal interest rate on short-term government debt will go to zero. Efforts to maintain a 2 percent ceiling on inflation have brought few concrete benefits and put policymakers in the unnecessarily difficult position of trying to conduct unorthodox monetary policy measures during a time of economic crisis when elites necessarily come under suspicion.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers