Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2316

May 12, 2011

Raising The Social Security Retirement Age Is Incredibly Regressive

If I were to say, "let's fix the Social Security gap with a benefit cut that hurts the poor really badly while largely sparing the rich" Beltway people would think that was a bit of an odd idea. But if I were to say, "people are living longer than ever, so let's raise the retirement age," I'd be the toast of Washington. The problem, as Aaron Carroll shows citing Hilary Waldren's research (PDF) is that these are equivalent ideas. Consider that not only do the rich live longer than the poor, but the gap has grown steadily:

So this is a terrible and terribly unfair idea.

I think that if people want to propose cutting Social Security benefits they should straightforwardly propose cutting benefits. Like we could reduce projected expenditures by five percent by cutting everyone's benefit levels by five percent. I understand that it seems "politically savvy" to try to devise complicated phase-ins or obscure what's happening with hide the ball moves, but the upshot is that you wind up with people proposing ideas whose implications they don't really understand. As we saw recently with Alan Simpson, in DC you don't need to know anything about public policy to be a senator or to chair important commissions so the odds that people who think they're merely fooling the voters are also going to end up fooling themselves are quite high.

My preference, as stated many times, is to not cut Social Security benefits at all. We currently have two programs dedicated to transferring resources to the elderly. One that gives the elderly money, and one that gives the elderly health care services. If there must be cuts (and there should be, even though they're not strictly necessary) they should come out of the health care services side. The US health care system is not such a model of efficiency that it makes sense to nudge people into consuming more of it if they'd rather buy something else, and the elderly are—by definition—old and not in need of heavy handed paternalism.

Senator Mike Johanns Joins The Monetary Crank Wing Of The Conservative Movement

It sure would be nice if the President of the United States were to address this issue. Until then, he'll just leave the field to the growing chorus of nutjobs:

A day before the Senate Banking Committee is due to vote on Diamond for the third time, the Nebraska senator said he couldn't back someone who has been so outspoken in favor of more government spending and of the Fed's easy-credit policies to lift the economy.

"We must be increasingly wary of the threat of inflation, yet the Fed continues to print money with reckless abandon," [Mike] Johanns [R-Nebraska] said in a statement. He had previously supported Diamond twice on the Senate panel, but opposition from Republicans later prevented a vote on the Senate floor.

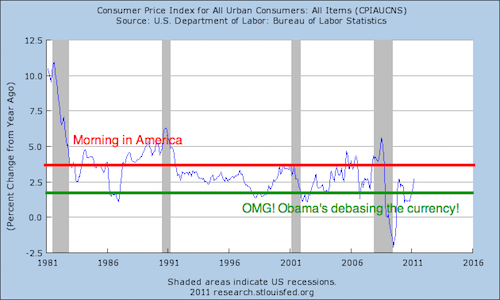

Recall my thirty years of inflation history:

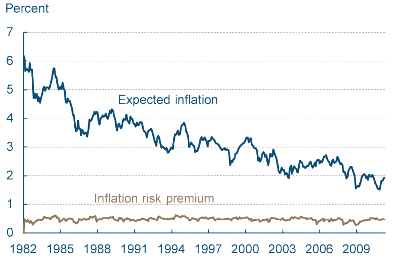

You might also be interested in the Cleveland Fed's historical data about inflation expectations:

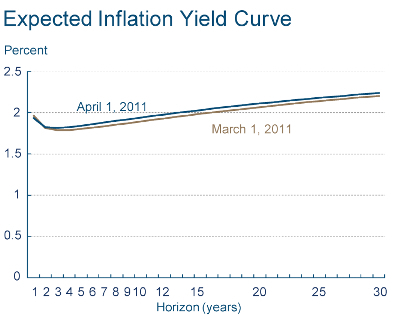

Or the fact that inflation is currently set to remain below the Fed's longtime 2 percent target for over a decade:

I'll be happy to entertain theories about structural employment from anyone as soon as we turn this situation around. But until then, all signs continue to point to an economy suffering from substantial excess capacity.

May 11, 2011

Endgame

Morpheus in this hip-hop matrix:

— David Brooks is still wrong about the sources of unemployment.

— Single-payer health care sneaking in from the north.

— The 18th century meaning of "commerce" was much broader than the one that's prevailed since the New Deal.

— "Obi-Wan Kenobi is Dead, Vader Says".

— Rush Limbaugh is a huge racist.

— Is the iPad killing PC sales?

— Buy:rent ratios still look very high in a number of metro areas.

Common, "The 6th Sense".

Congress Doesn't Want Power Over Whether Or Not The United States Keeps Bombing Libya

Doug Mataconis rounds up reporting on congressional concern about the looming expiration of the 60-day window for military action in Libya under the War Powers Act and finds that nobody gives a damn.

This returns us to the core point about executive unilateralism and warmaking powers—Congress is getting what it wants. Nobody is interested in trying to do anything around the War Powers Act, nobody is threatening to use the debt ceiling as leverage to assert congressional control over the war, nobody wanted to use the FY 2011 appropriations fight to assert congressional control over the war, etc., etc., etc. By contrast see how interested Congress suddenly becomes in military management any time any president of either party tries to cancel a weapons system or close a military base.

The upshot is that our system Congress has enormous power over all kinds of things but only if they actually want to use it. But over the years, Congress has shown very little interest in constraining presidential warmaking power. At times presidents have shown interest in demanding that congress vote on their war proposals—like when George W Bush forced a vote on invading Iraq timed right before the 2002 midterms but months before he initiated military action—but that's something initiated by the White House for political purposes. For most of the same reasons, members prefer to duck votes on these things when possible.

The Candidate Of Ideas

Dan Balz has one of these bizarre Beltway article where he writes over and over and over again about how Newt Gingrich is a huge ideas guy but doesn't actually name any of his ideas. Which is too bad, because Gingrich has actually been associated with some good ideas over the years. Take, for example, this 2007 joint appearance with John Kerry in which he accurately diagnosed the roots of conservative anxiety toward tackling the challenge of climate change and urged his fellow-travelers to get over it and recognize the need for action:

One great way of meeting this challenge in a manner consistent with conservative values would be to adopt an economy-wide cap on greenhouse gas emissions. Then we could auction off permits—ideally tradable ones—to engage in emissions. The revenue thereby raised could be returned to the American people in the form of offsetting tax cuts. That way there'd be no net increase in tax burden, and strong market incentives would exist for firms and households to improve their energy efficiency and for entrepreneurs to work mightily on the task of creating and deploying new green forms of energy. Perhaps this is the kind of idea that will be explored throughout the 2012 campaign.

Increased High-Skill Immigration Would Be A Major Boost To The American Economy

I've been asked a few times what I think of the Kerry/Lugar startup visa bill designed to create a special immigration category for foreigners who want to come here and start a business. My answer is basically the same as Annie Lowrey's—this is a find idea but far too restrictive thanks to "inflexible rules about sales, capital investment, and job creation."

Entrepreneurs who meet those targets are great, but anyone who comes to this country with skills is bound to provide a net boost to the economy. The United States of America isn't an agricultural country that needs to worry about being stuck with too many mouths to feed. We're a people-powered economy in which far and away our most valuable resource is the skills of our population. More architects, more scientists, more doctors, whatever, it'd all be good.

Internet Access Boosts Political Participation In Tanzania But Seems To Depress Engagement

Caitie Bailard wanted to better understand what impact using the Internet more might have on citizens of developing country like Tanzania that has a mixed record on freedom of the press, so she did this experiment:

To conduct the experiment, my research assistant and I recruited subjects at several congregation points throughout the community of Morogoro, including professional and trade schools, secondary schools, the main bus station, hair salons, and markets. We then randomly assigned individuals to either the experimental group (i.e. Internet group) or control group. The Internet group was then given 75 hours of Internet time at a local cafe (pictured above). By employing random assignment, this experiment can ascertain the causal influence of Internet use on political evaluations. By conducting this experiment in the field in a developing democracy in the months leading up to an actual election, this approach makes the experiment's setting more realistic.

The results are a bit funny. The Internet group seems better-informed and less under the thumb of the quasi-free established press: "Members of the Internet group were 15 percentage points less likely to believe that the election was conducted fairly and impartially. They were also 12 points more likely to believe that the recount was conducted unfairly when compared to the control group." On the other hand, the upshot of this isn't that they turned into committed reformers. Instead they were 11 percentage points less likely to vote.

Of course when you think about the United States, lots of people vote here. And whyever it is that we do it, it's not because we're responding to accurate information in a narrowly instrumental way. If you want people to vote you have to make them feel good about participating in the process, not increase their cynicism.

Fast Food and "Skimming"

Imagine a study showing that habitual KFC customers are happier than habitual Taco Bell customers. Someone might leap to the conclusion that KFC's food is more euphoria-inducing than Taco Bell's. But that could easily be wrong. Taste for one or the other Yum! Brands fast food chain might correlate with other demographic characteristics that themselves correlate with happiness. Religious people, for example, are happier than non-religious people. Like maybe Asian-Americans in addition to being less happy than white people are disproportionately inclined to like Taco Bell. Who knows? The point is that a happiness gap could easily be explained by some kind of demographic skimming rather than an actual difference in the food.

Checking that sort of thing is good statistical practice, and anyone who ignores it is doing sloppy work.

At the same time, it obviously wouldn't follow from something like this that the success of KFC as a business merely reflects pernicious skimming and that we need a fast food chain that serves all of America's greasy food lovers. On the contrary, Yum! owns both brands and seems to have decided that it makes more sense to keep them separate. Specialization helps enhance the efficiency with which they operate the restaurants, they can do more targeted marketing this way, etc. What's more, some markets really might have more demand for one or the other and it makes sense to focus on serving the demand that exists. At other times, the best way to manage a real estate portfolio is to co-locate a KFC and a Taco Bell in the same building. Either way, the fact that KFC and Taco Bell can focus on trying to undertake a relatively narrow array of tasks as well as possible is helpful to both chains, and the fact that customers can pick the option that suits them best is helpful to all diners. A manager being asked by corporate HQ to be all things to all people could legitimately complain that it's being given an unfair burden, but it couldn't reasonably complain that the solution to the unfairness is to disadvantage everyone.

Wednesday Bee Blogging

Having discussed the issue with a number of people I'm now persuaded that urban beekeeping poses no risk to innocent neighborhoods and thus withdraw all doubts about the wisdom of introducing honeybees to my neighborhood.

Meanwhile, Spencer Ackerman reports that bee stings could revolutionize bomb detection:

The science behind the Strano's sensor is complex. But here's the simplest way of breaking it down. Put bee venom on a carbon rod and you've got yourself a sensor.

Believe it or not, bees are powerful bomb sleuths. That's why Darpa wanted to enlist them to find explosives, landmines and "odors of interest" in the early 2000s. As it turns out, inside of every bee sting is a small fragment of a protein called a peptide that has an uncanny property.

"When it wraps around a small wire, that allows it to recognize 'nitro-aromatics'," Strano explains, the chemical class of explosives like TNT. That wire is a carbon nanotube, a mere one atom thick.

Of course I wonder if better security technology was developed would we actually use it. I'm never sure how much intrusive security is driven by terrorism paranoia and to what extent it's just a kind of makework jobs program.

Immigration As Freedom

I was watching an episode of the excellent BBC/Discovery Channel collaboration Human Planet the other day and it featured a bit on the Korowai people of southeastern Papua who were uncontacted until the 1970s and live in giant treehouses. It was pretty cool stuff. But it's also obviously a very difficult, very strenuous, very limiting life. If someone wanted to leave that life and go take a crummy job in a rich country, I'd find that very understandable. You could watch television, for example, and have access to basic health care services. Similarly, while I don't think the United States should take military action to halt the Syrian government's violent repression, I'd also find it very understandable if a Syrian person were to say to himself "this is a crappy place to live, I'd rather be in America."

But this kind of thing is generally illegal.

So I was glad to see Ryan Avent make the point that there's more to the immigration debate than the economics:

And economics side, we should support free immigration to the greatest extent possible based on liberal principles alone. People should be free to move and choose their own destiny. Governments shouldn't interfere with the right to immigrate any more than is necessary and certainly not to satisfy the nativist demands of unhappy citizens.

The freedom to move is a very important kind of freedom, and countries have ample reason to enhance it.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers