Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2314

May 13, 2011

The Sustainability of Greece

I'm not intimately familiar with the details of Greek public finance, but it does occur to me that sage words I keep reading in the American press about how Europe's leaders can't just keep kicking the can down the road and need to deal with Greece's basic insolvency strike me as unwarranted. In general, the capacity of large wealthy societies to allow festering problems to go un-addressed seems perennially underrated. I'll be thirty next week and for as long as I can remember people have been talking about how the United States needs to address entitlement spending and trade imbalances. And as best I can tell, we do need to address those things. Presumably at some point something will happen. But in practice we've managed a great deal of can-kicking, seem to have more can-kicking in us, and actually the public and the political elite alike are quite averse to the kind of steps that would address these issues.

Is Greece so different? Its output is, what, 2-3 percent of the total EU economy. As long as the money is owed to banks (rather than households who immediately need the money) that can be protected by complicit regulators, it doesn't seem mathematically implausible to do a great deal of extend and pretend. You may need some accounting gimmicks to make this work, but I don't think it's clear that the problem really has to be addressed unless true insolvency expands to bigger countries.

After Osama Bin Laden

In a piece for TAP online I argue that the killing of Osama bin Laden shows that we don't need to be fighting a war in Afghanistan and have essentially achieved the main objectives of launching the war:

Here are Bush's original demands:

—"Deliver to U.S. authorities all the leaders of al-Qaeda that hide in your land."

—"Release all foreign national including American citizens you have unjustly imprisoned."

—"Protect all journalists, diplomats, and aid workers in your country."

—"Close immediately and permanently every terrorist training camp in Afghanistan and hand over every terrorist and every person in their support structure to appropriate authorities."

—"Give the US full access to terrorist training camps so we make sure they are no longer operating."

Two key assumptions are at work here. One is that the Taliban was actively sheltering key al-Qaeda leaders. The other is that terrorist "training camps" operating in Afghanistan constituted a major threat against the United States. Neither of these is true anymore. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed is under American custody at the detention center in Guantánamo Bay. Osama bin Laden is dead. Anwar al-Awlaki is in Yemen. And no terrorist training camps have been operating in Afghanistan for years.

It's time to move on and to try to shift as far away as possible from the idea of a "war" on terrorism.

May 12, 2011

Newt Gingrich Used To Love Individual Health Insurance Mandates

Sam Stein deploys the power of Lexis-Nexis to discover that conservatives "man of ideas" Newt Gingrich has very similar ideas to Mitt Romney and Barack Obama about the desirability of an individual mandate to purchase health insurance:

In a June 2007 op-ed in the Des Moines Register, Gingrich wrote, "Personal responsibility extends to the purchase of health insurance. Citizens should not be able to cheat their neighbors by not buying insurance, particularly when they can afford it, and expect others to pay for their care when they need it." An "individual mandate," he added, should be applied "when the larger health-care system has been fundamentally changed." [...]

In 2008′s "Real Change," he wrote, "Finally, we should insist that everyone above a certain level buy coverage (or, if they are opposed to insurance, post a bond). Meanwhile, we should provide tax credits or subsidize private insurance for the poor."

Stein also quotes from a 2005 Gingrich book that was literally called "Winning The Future" and that describes the basic structure of the Affordable Care Act, up to and including the Medicad expansion:

"People whose income is too low should receive Medicaid vouchers and tax credits to buy insurance," he continued. "Large risk pools (association health plans are one model) should be established so low-income people can buy insurance as inexpensively as large corporations. Furthermore, it should be possible to buy your health insurance on-line to lower the cost as much as possible."

Endgame

I fell in love with you:

— Jews and Koreans need to stick together.

— In defense of diaspora cuisine.

— New urban policy news aggregator.

— Absent RomneyCare, who would even care about Mitt Romney?

— Harvard doesn't seem to be remotely worth paying for but as I say people pay for summer camp.

— I can't get enough of this giant school spending/poverty/performance interactive.

— For the great stagnation files.

I just can't quit Mitt Romney, so here's "Mass Pike".

Individualism And Insurance Are a Bad Match

My colleague Igor Volsky has five smart points about Mitt Romney's new health care proposals, of which I think point two is the most interesting:

Romney would "reform the tax code to promote the individual ownership of health insurance" and "give individuals a choice between the current system and a tax deduction to buy insurance on their own." He thinks this would create "the best of both worlds" by allowing certain individuals to leave their employer-sponsored health insurance plans and find coverage on the individual market. But this would only entice young healthy workers to buy cheaper but less substantive insurance in the individual insurance plan market place, increasing costs for sicker workers and forcing some to opt out entirely. Among those who would lose their health care are 56 million Americans with pre-existing chronic health conditions. The credits would also fail to cover the cost of comprehensive coverage.

I feel like our political system keeps spinning its wheels around the point. But the issue is that insurance is a matter of pooling risks. It works better if you have big pools. The federal civilian workforce is a really big pool. So is Medicare. So is the entire population of Canada. A typical large private employer in the United States isn't as good, but it's pretty big and it works pretty well. In principle, though, the United States should have a lot of advantages. We're much bigger than Canada and could create a truly enormous integral pool. Things that make it easier for random people to drop out of employer-sponsored pools sound pretty appealing. But if you do it à la Romney (or the somewhat similar John McCain campaign proposal) all you get is even more fragmentation. To make this idea work you need some regulatory measures—exchanges and mandates and risk-adjustment—to turn the individual market into a large pool.

That's why when Mitt Romney was governor of Massachusetts his health care plan had those features, and that's why the Affordable Care Act has them.

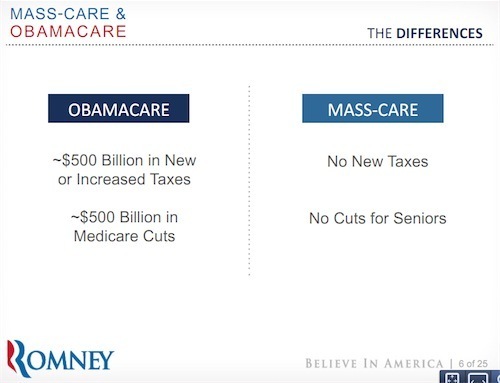

The Real Difference Between RomneyCare And The Affordable Care Act Is That The ACA Is Paid For

Today's Mitt Romney speech on health care contained a lot of nonsense, but this slide is accurate and important:

I really wish more discussions of why the Affordable Care Act is so controversial would start with this. The Affordable Care Act gives health insurance to millions of people who previously lacked it. That costs money. Money that the Affordable Care Act obtains through higher taxes (largely on the rich) and through reductions in spending (mostly subsidies to private insurance company Medicare subcontractors). That's some controversial stuff with a lot of money at stake. People don't like it.

And while Mitt Romney's universal health care bill in Massachusetts is very structurally similar to the ACA, it's not really paid for. The financing was a mix of Medicaid waivers, deficit-financed federal grant money, and hand-waving. I was fine with that stuff. I'm not really a "deficit hawk" guy. But there's something a little bit bizarre about claiming this as the distinctive virtue of the Commonwealth Care approach.

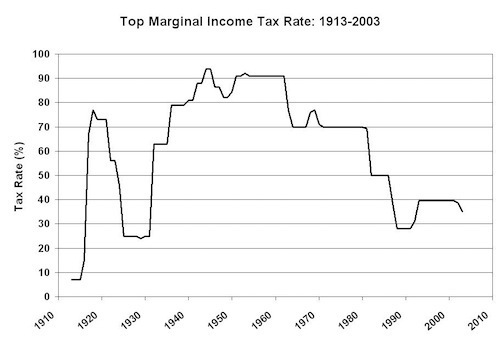

Taxing The Rich And Economic Growth

I think Ezra Klein has it about right here and that the main thing you need to know about American politics today on the level of ideas is the completely sincere belief of right-of-center thinkers in the idea that higher levels of taxation on the right will be economically harmful. If you're a progressive, it's worth marinating a bit in this idea to see how powerful it might be. The important thing to understand about it is that even a very small increase in the rate of economic growth—0.2 percentage points a year or something—has pretty gigantic benefits over the long run. In this frame, the central problem of political economy is that the hyper-empowered bottom 80 percent of the income distribution has the capability to short-sightedly vote itself more goodies by hiking taxes on the rich. These hikes will impede growth and do massive long-term harm to the true interests of the middle class and poor who essentially need to be saved from themselves.

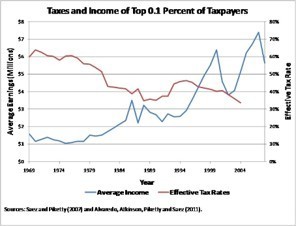

Now what's interesting about this is that the right has been winning this argument for decades. In particular, since the Kennedy administration we've seen very steady reductions in the marginal income tax rates paid by high earners:

Actual taxes paid have seen a different, though basically similar trajectory:

Obviously, the question to ask about this is "where's the growth?" And I think that's the context you need to understand a lot of what's going on in political debates today. One obvious reply is that it turns out that high income taxes on the wealthy aren't actually that big a deal.

Richard Lugar Abandons The DREAM Act And Illustrates Why America Can't Have Nice Things

Senator Richard Lugar of Indiana says he . Lots of politicians don't support the DREAM Act, but what's a bit surprising here is his reasoning. As recently as the 111th Congress he thought the DREAM Act was a good idea. And here in the 112th Congress he doesn't say that he's changed his mind on the issue. Instead, he says he's now unwilling to vote for the DREAM Act out of spite for Barack Obama:

Lugar's spokesman said Lugar did not join Democrats in reintroducing the federal legislation to help children of illegal immigrants – known as the DREAM Act, or Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors – because Democrats have politicized the issue.

"President Obama's appearance in Texas yesterday framed immigration as a divisive election issue instead of attempting a legitimate debate on comprehensive reform," said spokesman Mark Helmke. "Ridiculing Republicans was clearly a partisan push that effectively stops a productive discussion about comprehensive immigration reform and the DREAM Act before the 2012 election."

Adam Serwer calls this , which it is. But it also suggests the paradoxical nature of presidential "leadership" in a polarized political environment. Bipartisan legislative initiatives are useful to congressional Republicans basically only if the President opposes them. Something like the ridiculous McCaskill-Corker CAP Act is great precisely because it's a totally terrible idea. Barack Obama can be counted on to resist it, so criticizing him for opposition to this bipartisan measure makes sense. By contrast, if Obama wants to turn himself into a zealous advocate of a bipartisan bill like the DREAM Act, then that renders it toxic. And since the direct beneficiaries of the DREAM Act are ineligible to vote and don't have much campaign cash to offer, that becomes all you need to know.

I'm not one to scold politicians for playing politics. That's life. But we have a set of political institutions right now that that make it very difficult for politics-playing politicians to actually address any important problems of national significance.

Phlogiston Economics

Richard Thaler wants to bring back the old word "aether" that used to refer to the (non-existent) medium through which waves of light pass, the way sound waves pass through air:

Aether variables are extremely common in my own field of economics. Utility is the thing you must be maximizing in order to render your choice rational.

Both risk and risk aversion are concepts that were once well defined, but are now in danger of becoming Aetherized. Stocks that earn surprisingly high returns are labeled as risky, because in the theory, excess returns must be accompanied by higher risk. If, inconveniently, the traditional measures of risk such as variance or covariance with the market are not high, then the Aetherists tell us there must be some other risk; we just don't know what it is.

Similarly, traditionally the concept of risk aversion was taken to be a primitive; each person had a parameter, gamma, that measured her degree of risk aversion. Now risk aversion is allowed to be time varying, and Aetherists can say with a straight face that the market crashes of 2001 and 2008 were caused by sudden increases in risk aversion.

I think I'd prefer the use of the term "phlogiston" for these purposes, but I think it's a good point. In Kuhnian terms, we're at a point where the prevailing academic approach in macroeconomics is accumulating more problematic anomalies but behaviorist critics haven't really produced a workable alternative paradigm. Consequently, actual practical policymakers are relying a lot on economic history, intuition, etc.

The Right Connection Between Housing Policy And Education

I'm largely in agreement with what Joel Klein writes about K-12 education policy in the new Atlantic, but there's a passage that I think reveals an important blind spot in this conversation:

Public education lacks both kinds of accountability. It is essentially a government-run monopoly. Whether a school does well or poorly, it will get the students it needs to stay in business, because most kids have no other choice. And that, in turn, creates no incentive for better performance, greater efficiency, or more innovation—all things as necessary in public education as they are in any other field.

A full-scale transition from a government-run monopoly to a competitive marketplace won't happen quickly. But that is no reason not to begin introducing more competition. Many middle-class families have plenty of choice (even beyond private schools): they can move to another neighborhood, or are well-connected enough to navigate the system. Those families who are least powerful, however, usually get one choice: their neighborhood school. That has to change.

This naturally raises the question of why do any government agencies work well at all. And this, I think, much more than the segregation issue gets at the really deep connection between housing policy and education policy. After all, lots of important things are done by government monopolies in this country. It's not just K-12 education, it's also transportation and criminal justice. But most Americans are happy with their local school, most Americans live in places with low crime, most Americans get to work every day, and generally speaking life in the United States of America is pretty good. And that's of course because most Americans pick up and move if they find that the local mix of services and taxes is intolerable. Consider that both Baltimore and Washington, DC are considerably below their peak population levels even though the Baltimore-Washington Combined Statistical Area has seen enormous growth. Ineffective schools and ineffective law enforcement have led people to choose to live elsewhere.

So what about the poor? Well they "can't afford to" move to the suburbs. But why not? Well in large part because these suburbs tend to have an array of rules—minimum lot size, minimum lot occupancy ratio, rules against multi-family dwellings, parking minimums, maximum building height, etc.—designed to ensure that expensive land leads to expensive houses rather than to intensive land use.

Now if you're running the New York City school system you can't do anything about this, so it's still incumbent upon you to do the best you can to make the schools operate as well as possible. But from a national perspective, it's still a really big deal. The practical ability to leave a place that's not working and go someplace else is very valuable. What's more, though it's not within the school chancellor's jurisdiction, there is an important local government angle. After all, Washington DC is actually an expensive place to live notwithstanding high crime and bad schools. If we had excellent schools and low crime, would that improve the lives of the poor or just turn DC into another place that poor people can't afford to live? Ultimately if your specific concern is delivering high-quality public services to poor people (who are, after all, the people who need them most) then you need to spend some time worrying about a state of play in this country that largely prices poor people out of wherever the quality of life is high.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers