Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2275

June 14, 2011

Beyond 'Men Behaving Badly'

Via Shelby Knox, Marlo Thomas argues that certain recent high-profile scandals are good for feminism. There's something to her case, but I really want to object to this framing:

Strauss-Kahn. Schwarzenegger. Edwards. Weiner. It's been a helluva month for men behaving badly. Am I the only one who sees this as a good thing?

Obviously Dominique Strauss-Kahn is in fact a man. And trying to rape a hotel maid is not good behavior. But Arnold Schwarzenegger has been exposed in a classic "sex scandal." John Edwards took a sex scandal and added some serious campaign finance improprieties as part of the coverup. Anthony Weiner engaged in what's really a pretty minor league sex scandal in the scheme of things and compounded the error by lying about it to the press. DSK, by contrast, allegedly committed a serious violent crime. The sort of thing for which people, quite rightly, get sent to jail. This all in some sense exists on a continuum of bad behavior, but I think we should really resist lumping it all together as the same kind of thing.

Tim Pawlenty's Big Whiff

I think Josh Marshall is almost certainly overstating the significance of Tim Pawlenty's big whiff when he choked and failed to nail Mitt Romney when asked about the Obamneycare construct. Little campaign moments just don't matter that much. But Pawlenty's problem isn't so much that he hurt himself there as that he didn't help himself. Pawlenty's has lower name-recognition than Romney, less money than Romney, and worse poll numbers than Romney. He's the "obvious" sensible alternative to a candidate who many conservatives deem ideologically unacceptable, and yet he's consistently failed to generate the kind of grasstops enthusiasm that you need to actually win. So while little moments tend not to matter, Pawlenty really needs to help himself by making some moments matter.

A debate is a potential opportunity for a candidate with less money and less name ID. Maybe you can do something that makes a dedicated activist in New Hampshire feel better about you. Maybe you can show a South Carolina state legislator that you've got more mojo than he's heard. Maybe you can generate some buzz at a conservative church group. And Pawlenty didn't do anything like that.

It all reenforces the sense that conservatives are Waiting For Rick Perry, hoping for the emergence of a figure that will let them evade the Romney or Bachmann choice they'd rather avoid.

Nokia Finds New Life As Patent Licenser

Once leading mobile phone maker Nokia is on the ropes, first overtaken by Apple as a sexy smartphone maker and then crushed under the meteoric rise of Android-powered smartphones. But there is a new hope! Patent litigation. Specifically, Nokia has resolved its lawsuit against Apple with a settlement that involves both a one-time payment and ongoing royalties for iPhones and iPads. Interestingly, this isn't even a bad deal for Apple:

In the statement, Nokia pointed out that it has invested approximately EUR 43 billion in research and development over the last 20 years, building up a patent portfolio with over 10,000 patent families. The agreement is expected to have a "positive financial impact" on Nokia's quarterly earnings.

Legal pundit Florian Mueller viewed the settlement as a favorable outcome for Apple shareholders, despite the fact that Apple has to pay. According to Mueller, the agreement comes as a "sweet defeat" for Apple because competitors building Android-based devices will also likely have to pay Nokia, possibly paying more per-unit because rival handset makers may have less intellectual property to use as bargaining chips.

What's more, Apple has tons of cash on hand and super-high profit margins. The people for whom this promises to be a big headache are, as usual, not the incumbent players but hypothetical future players. Imagine a firm that's not currently a highly profitable, super-successful manufacturer of mobile devices. Now you've got a new barrier to entering the market. In other high tech news, Microsoft and other device manufacturers are filing suit to try to block Google's purchase of network equipment maker Nortel. Google wants Nortel for its patent portfolio, but Microsoft claims a "worldwide, perpetual, royalty-free license to all of Nortel's patents" as a result of a 1996 deal that apparently Google doesn't recognize.

I don't have a super-clean policy point to make about this, but it's striking how much time and energy is spent in this most vibrant and innovative sector of the economy on these patent wars. It's an equilibrium that's obviously wonderful for patent lawyers, and seems to serve all the major incumbents well enough but I don't think it really bodes well for the world. When firms engage in an arms race to hire more and better engineers to build better products, we all end up reaping gains. A battle to hire more and better lawyers to craft better litigation strategies is, by contrast, a zero-sum thing or even a negative-sum one if at the margin it persuades some bright hard-working people to become lawyers rather than engineers.

Structure Of U.S. Institutions Discourages Politicians From Framing Intelligent Choices

I really liked Clive Crook's column on Tim Pawlenty's fantasy budgeting, and particularly the use of the term "idiotic farrago" to describe it. But I'm afraid his last paragraph has inspired me to defend the honor of American politicians, Pawlenty included:

One way or another, the US is finally going to collide with fiscal reality. There need not be a crisis: deals might yet be cut to make this collision less violent. What seems ever less likely, though, is that the country's politicians will frame intelligent choices to put before voters, or that voters will insist that they do.

Rather than blaming politicians or the voters for this state of affairs, I think it's much better to blame the voters. Imagine a scenario in which both sides agreed to stop bickering about the long-term deficit for now. We just do a "clean" increase in the debt ceiling and then agree to the following. Both the Democratic Party and Republican Party congressional leaders have three months to write down long-term fiscal plans, à la the Peterson Summit exercise. Then after the plans are released on Sept. 14, they'll get CBO and Tax Policy Center scores, and on the first Tuesday in November, the country will vote on a binding referendum to choose between the plans. Maybe I'm just a utopian, but I think this would produce pretty good results. That's because both sides would have strong incentives to win the referendum.

The congressional bargaining process and the presidential campaign have a totally different structure. Let's say you're an influential donor sincerely convinced that both high levels of borrowing and high marginal tax rates are a real threat to American. Under the referendum scenario, you recognize that if the Democrats win the vote, MTRs are going to go way up. So the best strategy for minimizing MTRs is to ensure that the GOP puts something reasonable on the table so as to actually win. But if you're just voting in a GOP presidential primary, you're not actually looking for the candidate with the most reasonable plan. You're looking for the candidate who sends the strongest, most credible signal of tax-aversion. That militates in favor of extreme proposals. Similarly, the congressional bargaining process is skewed toward encouraging people to mark out extreme claims in order to push the "center" of debate closer to their ideal point. One of the alleged virtues of a political system laden with veto points is that in order to get anything done, politicians ultimately need to bargain and compromise with each other. But the flipside is that a system that depends much more on post-election bargains between elected officials than on decisive electoral victories encourages a lot of posturing as a negotiating tactic. Personally, I don't like this feature of the system but it's really a case where if you want to complain, you should hate the player and not the game.

June 13, 2011

House Republican Budget Confirms That Life Begins At Conception And Ends At Birth

I was thinking to myself the other day, "You know what sucks? All this wasteful government spending on improving nutrion for babies." I mean, sure, a baby's got to eat, but if the baby's hungry, it should have thought of that before it was born, you know, and made sure to have richer parents. Fortunately, the House Republican caucus has approved a budget that will finally grapple with the problem of over-nourished infants and the country's shameful coddling of poor pregnant mothers. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, somewhere between 200,000 and 350,000 poor children and pregnant mothers will be dropped from the wasteful WIC program by their proposed cuts.

Reading this kind of thing makes me regret even sparing a moment for some wonky thoughts about early childhood education. We're apparently a country where we don't even have a political consensus around providing adequate food to poor kids, so asking for them to get education too is obviously a tall order.

In Practice, State-By-State Analysis Of Presidential Elections Doesn't Tell You Much

Formally speaking, the presidential election is a series of state-by-state elections. But Jonathan Bernstein chides up and coming pundits and Dylan Matthews for giving too much credence to the idea that we should be peering into the specific details of the employment situation in key swing states.

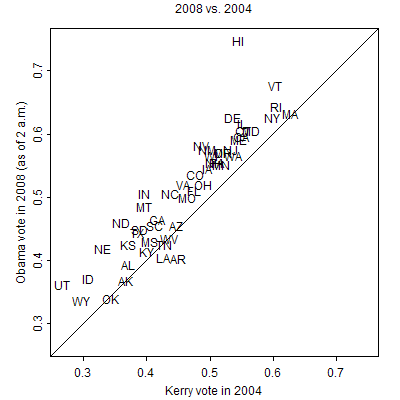

The case against worrying too much about the Electoral College is summed up by this chart from Andrew Gelman. He shows that despite claims from the Obama campaign to have redrawn the electoral map, what they actually did was do slightly better than John Kerry all across the country:

You'll note that there's absolutely no sign that Barack Obama crafted a message designed to appeal to voters in Rhode Island, didn't buy ads in the Providence media market, didn't do a broundbreaking GOTV targeting effort in Rhode Island, etc. But he did better in Rhode Island than John Kerry did, by approximately the same extent as he improved in the swing states which, again, was about the same as how he did in a deep red state like Idaho.

That said, what this chart primarily says to me is that state effects are so small as to be uninteresting except in the interesting elections! The fact that the pro-Obama swing was bigger in North Carolina and Virginia than in Ohio and Missouri wound up not mattering because the 2008 election wound up not being very close. But Ohio was still a bigger state than North Carolina and a more Democrat-friendly one. You can easily imagine an alternative, closer version of the 2008 election in which instead of Obama narrowly winning North Carolina he ends up narrowly losing Ohio. In that case the fact that Obama got a relatively strong swing in North Carolina and a relatively weak one in Ohio would have been very interesting and we'd probably have spent a lot of time focused on the fact. In other words, these idiosyncratic state effects are generally quite modest in their scale, but the winner-take-all nature of the Electoral College means that in a close election even a very small effect could be a big deal.

No Escape From School Quality

Kevin Drum says that "in an environment of limited resources, our highest priority ought to be programs that we already know how to implement and that have proven bang for the buck" rather than talking about how to improve the performance of K-12 schools. To that end, he should be excited about the Ready To Learn Act introduced last week by Sens. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Al Franken (D-MN).

I'm all for more investments in preschool, but it continues to be the case that I see no particular reason to believe that talking about four-year-olds rather than ten-year-olds or sixteen-year-olds gets us out of the quality quandry. What we know from the research into preschool is that good preschool programs make a huge difference to kids' outcomes. But what we know from the research into K-12 schooling is that good K-12 schools also make a huge difference to kids' outcomes. The challenge in both cases is to actually provide quality at scale.

According to the Murray/Franken press release on their bill, "To ensure high-quality programs that properly prepare children to be ready to learn, state plans will require qualified teachers, a developmentally, culturally and linguistically appropriate early learning curriculum and support for professional development." The question we have to ask ourselves is does writing down some standard of what degrees you have to have in order to count as "qualified" really ensure that the programs will be high-quality? What if preschool teachers can be roughly equal in their qualification but still vary widely in the actual quality of their teaching? I'm happy to spend any quantity of money anyone cares to propose on expanding access to preschool. Insofar as there's low-hanging fruit to be plucked in American education, this is where it is. And certainly if you're concerned about the future of this country, it makes more sense to worry about whether we're teaching little kids than about whether or not there will be a national debt to pay off when those kids are old. But it's not obvious how to run a really excellent preschool classroom any more than it's obvious how to run a really excellent sixth grade classroom. There's no escape from the challenge of providing schools that are actually effectve.

The Secret To Texas' Success: They Build Houses There

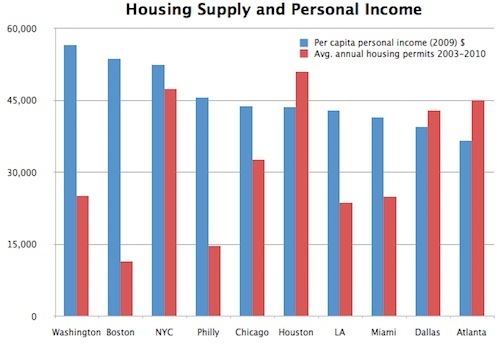

I've been looking at this same issue from a number of different directions for a while now, but the key point is that when you hear about Texas' economic success over the past decade it's worth understanding what specifically has driven the growth. And to a large extent it appears to be the case that people are moving to Texas largely because Texas is where you can build houses.

Consider this chart looking at America's largest Metropolitan Statistical Areas in terms of per capita income and in terms of average new home permits since 2003 (OMB changed the definition of metro areas that year, so it's hard to get comparable data going further back):

The big East Coast metro areas are all richer than Houston, suggesting that something's going right in the northeast. But DC, Philadelphia, and especially Boston were authorizing very little homebuilding during this period. By contrast, Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, and NYC are all acting like metro areas that want people to move to them. So in a sense, good for everyone! The places doing really poorly are places like Detroit that are neither rich nor growing. But from a national perspective, it's a little perverse to have so many people moving to Dallas when the opportunities seem better in Boston or DC. These days most people work providing services to other people, so it's generally advantageous to be providing those services someplace where incomes are high. But people can't move to Boston, on net, if it's not possible to build houses in the Boston area.

Greek Default Threatens Money Market Run That Treasury May Be Unable To Halt This Time

The phrase "the financial crisis" means many things to different people, but in its narrowest, most precise sense, it refers to the fact that after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt a mutual fund called the Reserve Fund "broke the buck" (i.e., lost money) which threatened an economy-wide run on money market funds. Money market funds are where most firms park their short-term savings, so a run on money market funds threatened to create a situation where all kinds of businesses would be suddenly unable to make payroll or finance accounts payable. Bad news, in other words. The responses to this were for the government to implicitly commit itself to not letting more large banks fail ("too big to fail" would be better known as "too likely to prompt a money market run to fail") to guarantee existing money market funds, and ultimately to move to enact TARP.

But according to Landon Thomas, Jr.'s reporting for the New York Times (hat tip Tyler Cowen), there's a threat of this happening again. This time not with the failure of an investment bank, but with a failure of Greece to pay its debts. Apparently "as of February, 44.3 percent of prime money market funds in the United States were invested in the short-term debt of European banks" including "French banks like Société Générale, Crédit Agricole and BNP Paribas" with significant exposure to Greek debt.

This time around, though, there may be a problem. As Brian Beutler explained last July, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street regulatory overhaul deprives Treasury of the legal authority that was used to backstop money market funds at the time. When Treasury officials were asked about this at a meeting with bloggers several months ago, they gestured in the direction of the idea that their resolution authority tools would help avoid a replay of the whole scenario. But Dodd-Frank obviously doesn't give the Treasury Department the authority to engage in an orderly liquidation of Greece. That means, as best as I can tell, that we're left to hope the folks running the European Union know what they're doing even though very little in their recent performance bolsters that hope.

'The Glorious Cause'

With Robert Middlekauff's The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 I've now read six of the ten published volumes of the Oxford History of the United States and I have to say that it's just a really excellent series. These kind of broad surveys are most helpful when dealing with a period you don't know anything about, and Middlekauff is covering the relatively familiar terrain of Revolution and Founding so it doesn't stand out quite as much as, say, the Wood or Howe books on the early 19th century. But it's still quite good. In particular, though America is kind of soaked in information about the personalities of the era the predominant form is the biography, which winds up obscuring all context. The wider view gives you a better sense of what's actually going on.

The main theme is the ways in which America changed over the course of a struggle that, though certainly not a "social revolution" was nonetheless a prolonged political and military undertaking that entailed mass participation and naturally involved substantial changes. The war was fought in part because people had a sense of their own identities as Americans and the rights that entailed, but the process of fighting for those rights, and then for independence, and then to create a workable system of government also brought that consciousness into being. Middlekauff remarks that the American Revolution is remarkable for seeming so inevitable in retrospect while simultaneously having been so unforeseen at the time.

The disappointment of the book is in terms of what it doesn't cover. As a volume in a History of the United States it's very focused on what the Revolution meant for America and Americans. That means that in terms of the war qua war you get scanty treatment of the global strategic situation and the thinking in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Madrid. The war was substantially unleashed in parliament, where there was no willingness to renounce taxing power over North America, and it was won there as well when English elites decided that pouring more resources into trying to establish that principle didn't make sense. That said, a book can't be everything and this is a good one.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers