Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2273

June 15, 2011

Low Productivity At The Movies

Attempting to get ourselves some culture, my girlfriend and I watched the 1944 film noir classic Double Indemnity last night. It's a great film and very much worth your time, but cinematic qualities aside watching an old movie like that is a fascinating window into daily life at a time of much lower labor productivity than you have today.

The protagonist of the film is an insurance salesman, and it's striking to think about a time when it made sense to do that job by actually traveling door-to-door to have in-person conversations with people about how they should buy insurance. Similarly it's taken for granted that you might make a separate trip to pick up an insurance check in person. And that's to say nothing of the basic office functions of an insurance agency. In a couple of shots you get a glimpse at the vast quantity of dudes at desks who'd need to sit around with papers and pens shuffling documents around in a world without computer filing systems. Then you can think about needing to consult actuarial tables rather than being able to plug numbers into a computer. The flipside of all that manpower being necessary to perform that kind of work is that the apartment building where the salesman lives manages to employ a full-time garage attendant who'll hand wash your car for you.

It's interesting, in part, because when we talk about technology displacing workers from jobs we normally do that with a manufacturing frame in mind. Fewer workers, more robots. But the displacement of office workers from routine tasks must be an equally big story. And in some ways it seems like the reverse of the usual "skill-biased technological change" story. Computers are quite good at replicated large segments of office work (basic record keeping, arithmetic, data retrieval, message taking, etc.) that require a modicum of math and literacy skills but thus far haven't made much progress at refolding sweaters or pouring cups of coffee.

A Better Payroll Tax Cut

The top idea floating around for politically viable additional stimulus seems to be a temporary reduction in the employer-side payroll tax. That would help, but it seems exceptionally inefficient to me since clearly the overwhelming majority of the funds would just go to temporarily increase the profitability of currently profitable businesses. But David Leonhardt's column offers a better idea:

Any business that increased its net employment could be exempted from payroll taxes on new workers for a few years, creating a big incentive to hire instead of, say, buying new machines. The exemption could be retroactive to June 1, so that companies would not wait to hire until after the bill passed.

Corporate lobbyists defeated this idea last time — because executives wanted federal money even if they were not hiring — but that's just self-interest.

That targets the labor market in a smart way. And since it's so much less costly than a broader employer-side cut, you could make it extend a lot longer and create much more serious hiring incentives.

Parenting Magazine Says DC's A Great Place To Raise Kids

[image error]

In fact, they say DC's the best place to raise kids!

Ordinal lists are always a little silly, but I think there's something to the magazine's points. On the other hand, the obvious drawbacks to raising kids in Washington are bad public schools and high housing costs. But what I think ought to be particularly worrisome to the city's policymakers is the fact that the housing costs are high despite the fact that DC's students perform below average for big city schools. Our poor kids do worse than an average city's poor kids, and our non-poor kids do worse than an average city's non-poor kids. The Fenty administration has pioneered some promising reforms to try to turn this around, and Vince Gray appears to be largely staying the course. I hope this works out, but people ought to think harder about the fact that if the school system does improve we can expect housing to become even less affordable. What ought to happen is that if DC becomes a more attractive place to live, we respond by building lots more buildings. But for the past ten years we've had a population growing at a below-average rate while real estate prices grow at an above-average pace.

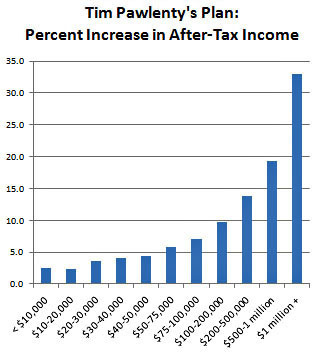

Tim Pawlenty's Exciting Tax Plan

The knock on Tim Pawlenty is that he's boring, but there's nothing boring about this Tax Policy Center analysis of the distributional impact of his tax plan:

Now of course pointing out that this seems unfair is just "class warfare" and fails to account for the pro-growth nature of the regressive tax change. But note something important. The positive growth impact of regressive tax cuts is often justified in terms of creating incentives to save and invest. But part of Pawlenty's economic plan is embracing the George W Bush theory that regressive tax cuts don't need to be paid for with unpopular offsetting spending increases. But if you borrow the money that you're using to increase incentives to save and invest, you can't increase the economy-wide savings rate. It's just money borrowed from the future to put into the pockets of the rich people of today.

Exciting!

Strategic Air Power Still Doesn't Really Work

Will air power advocates ever learn?

Almost three months into the campaign of air strikes, Britain and its Nato allies no longer believe bombing alone will end the conflict in Libya, well-placed government officials have told the Guardian.

No surprise to anyone who's seen this movie before, but apparently when you get put in charge of military aircraft all recollection of history vanishes.

Banks vs Patent Trolls

Sort of like with the Iran-Iraq War, the ideal scenario would be for both sides to lose:

For years and much to their frustration, big banks have paid hundreds of millions of dollars to a tiny Texas company to use a patented system for processing digital copies of checks, making Claudio Ballard, the inventor of the system, a wealthy man and the bank industry's biggest patent foe. After years of fighting Mr. Ballard at the federal Patent Office, in court and across a negotiating table, the banks went to see one of their best friends in Congress, Senator Charles E. Schumer of New York, who inserted into a patent overhaul bill a provision that appears largely aimed at helping banks rid themselves of the Ballard problem. The Senate passed the bill easily in March.

To me, though, the idea of getting rid of the "Ballard problem" through an ad hoc bill typifies everything that's going wrong with American politics. The patent system in the United States is sufficiently broken that it harms the interests of all kinds of people, including politically powerful bank executives. But instead of their power being applied to generate momentum for some kind of reform, their power is being used to create an ad hoc provision that will let them slip the leash. If this gets done, the prospects for systematic reform get even bleaker and little guys who can't get Senators to insert special provisions into legislation on their behalf get even worse.

One TRILLION Dollars

As I prepare for tomorrow's panel on progressive monetary policy, do take note of panelist Mike Konczal's Q&A with Joe Gagnon who explains many things and calls for a big additional round of monetary stimulus:

What should QE3 look like?

A lot of the benefit of telling the markets that you aren't going to allow deflation is already out there. You could re-enforce that, but the major effect is out there already. They would need to do a bigger number. There's no point in doing it unless it's at least $1 trillion dollars.

The floor is set. The market is reassured against fears of deflation. Can QE3 return to trend and full employment?

While QE2 had good effects, it was too timid. A QE3 needs to be bigger than QE2 — you want to signal a larger amount. A trillion dollars sounds like a big number, but it isn't like a trillion dollar tax cut. All it is is a swap of two different assets. Buying one kind, selling another.

You need to say that one TRILLION dollars stuff with a Dr. Evil voice. But I completely agree. Later in the interview, Gagnon makes the point that under present circumstances, monetary stimulus and fiscal stimulus are two great tastes that taste great together. And indeed my preference would be that rather than on the one hand talk fiscal policy and on the other hand talk somewhat convoluted quantitative easing, we just talk directly about so-called "money financed" tax cuts or spending initiatives.

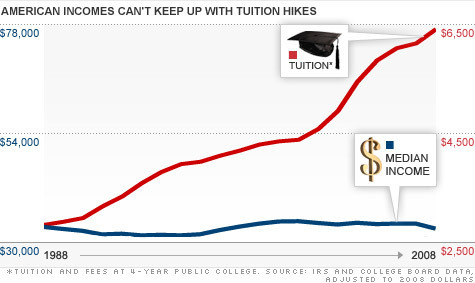

Balancing The Budget With Pell Grant Cuts

The Pell Grant program has seen a lot of spending increases in recent years, and the president's budget proposal involved the idea of rolling it back a bit around the margins in order to preserve the sustainability of the program's core functions. But as deficit reduction costs continue, one option under consideration is just doing some cuts for general deficit reduction. In light of the skyrocketing cost of college tuition, this would be a pretty unfortunate choice:

It's true that ultimately the college affordability situation calls for a more systematic remedy than grants for poor kids. This trajectory is so bad that you can't just fill the gap with ever-rising subsidies forever. But at the same time, even though "bending the curve" of tuition costs would be a very worthwhile subject for bipartisan talks, that's not what DC's focused on right now. They're talking about cutting spending on subsidies for poor families without doing anything more systematic on the cost structure of higher education. It's incredibly punitive to students in need, and considering the major nationwide benefits of a more educated, more skilled population, it's incredibly shortsighted to boot.

Late 18th Century Rentier Politics

My new year's resolution has been to spend more time reading random things, and it's delightfully turned out that random things do a surprising amount to illuminate things I'm working on. For example, a few separate essays in Gordon Wood's collection The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States shed surprising light on some of the discussion in the progressive blogosphere of the political economy of deflation.

He argues that the "republican" ideology that prevailed in the late 18th century held that public officials should be disinterested participants. But they needed some form of income. Ideally, that income would take the form of land rents. But under American circumstances, interest payments might have to substitute:

But with the exception of rents from property, most such direct sources of income were defiled by interest. That is, the income of most American gentlemen did not come without work and participation in commerce, as Adam Smith suggested it ought to for leaders to be truly disinterested. The "revenue" of the English landed aristocrats was unique, said Smith; their income from rents "costs them neither labour nor care, but comes to them as it were, of its own accord, and independent of any plan or project of their own." Thus would-be disinterested American public leaders struggled to find an equivalent, a reliable source of income that was not stained by marketplace exertion and interest. Many gentlemen of leisure found such a source in the interest from money they had lent out. It is not surprising that so many of the gentry used their wealth in this way. After all, what were the alternatives for investment in an underdeveloped society that lacked banks, corporations, and stock markets? Land, of course, was a traditional object of investment, but in America, as John Witherspoon pointed out in an important speech in the Continental Congress, rent-producing land could never allow for as stable a source of income as it did in England. In the New World, said Witherspoon, where land was more plentiful and cheaper than it was in the Old World, gentlemen seeking a steady income "would prefer money at interest to purchasing and holding real estate."

Of course "disinterested" people of this sort weren't actually disinterested. Instead, they had strong economic interests in perpetuating slavery and avoiding inflation.

And, indeed, James Madison was very upset about inflation:

In his working paper drafted in the late winter of 1787 entitled "Vices of the Political System of the United States," Madison spent very little time on the impotence of the Confederation. What was really on his mind was the deficiencies of the state governments: he devoted more than half his paper to the "multiplicity," "mutability," and "injustice" of the laws passed by the states. Particularly alarming and unjust in his eyes were the paper money acts, stay laws, and other forms of debtor-relief legislation that hurt creditors and violated individual property rights. And he knew personally what he was talking about. Although we usually think of Madison as a bookish scholar who got all his thoughts from his wide reading, he did not develop his ideas about the democratic excesses of the state governments by poring through the bundles of books that Jefferson was sending him from Europe. He learned about popular politics and legislative abuses firsthand—by being a member of the Virginia Assembly.

Last (but first in the book), Wood draws a contrast between noting that ideas and interests were bound together, and making the vulgar argument that the constitution was nothing but a plot to advance the interests of creditors:

Such realists or materialists—that is, the Progressive historians—may be right that ideas do not "cause" behavior, but it does not follow that ideas are unimportant and have little or no effect on behavior, or that they can be treated as just one "factor" that now and then comes into play in human experience. Otherwise we would not spend so much time and energy arguing about ideas. I think it is possible to concede the realist or materialist position—that passions and interests lie behind all our behavior—without deprecating the role of ideas. Even if ideas are not the underlying motives for our actions, they are constant accompaniments of our actions. There is no behavior without ideas, without language. Ideas and language give meaning to our actions, and there is almost nothing that we humans do to which we do not attribute meaning. These meanings constitute our ideas, our beliefs, our ideology, and collectively our culture. As we have learned from both "the linguistic turn" and "the cultural turn" over the past several decades, our minds are essential to the ordering of our experience.

In other words, the leaders of the early republic had an ideological account of what sort of person was suited for public office. That naturally led to an ideological account of what sort of interests were legitimate. If a creditor isn't just a member of an interest group, but actually someone earning a living in a uniquely virtuous way, then those advancing an inflationary agenda are a uniquely pernicious brand of conspirators.

Test Your Economic Intuitions As Wilson Middle School Replaces Groundskeepers With Sheep

A charming tale of eco-utopia from TreeHugger:

According to a report from The Patriot-News, cutting the grass around Wilson Middle School's field of solar panels used to take workers 6 hours a week — and throughout the year, the cost of lawn maintenance really added up. But now, thanks to the appetite of a herd of 30 or so sheep, they've cut that figure down to virtually nothing.

Or is this just another sordid tale of union-busting? Alternatively, do we need to worry that a decade from now, school districts are going to be groaning under the cost of veterinary bills and sheep pensions? Will the sheep some day be threatened with replacement by goats or llamas only to form unions of their own to object to these efficiencies?

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers