Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2263

June 25, 2011

Fed Fiddling As Inflation Expectations Tumble

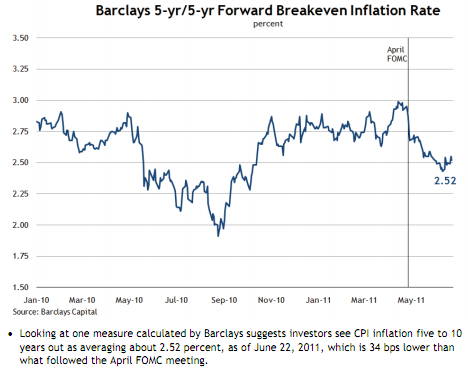

Nice chart from the Atlanta Fed's latest big set of charts (PDF) shows that inflation expectations have tumbled since the April FOMC meeting:

This is, again, a reminder of how bizarre the Fed's stand pat attitude is. If inflation expectations had gone up by a large amount since the last meeting, there's no doubt that the Fed would have responded with tighter money. So why doesn't a fall in inflation expectations lead to looser money?

America's Increasingly Lazy Rent-Seekers

I'm slightly amazed by the frequency with which you read local news stories in which some rent-seeking special interest group doesn't even bother to come up with a public interest rationale for its agenda. Take taxi reform in New York:

Yellow taxis, with medallions that fetch nearly a million dollars at auction, have long dominated city politics and have the exclusive right to pick up street hails in the city. The agreement, if it passes, would be a rare loss for the industry, which had argued that giving liveries the right to pick up passengers who don't call ahead would destroy the value of taxi medallions.

Presumably relaxing the scope of the yellow cabs' monopoly will, in fact, reduce the value of taxi medallions. But what kind of reason is that? Should New York City have prohibited digital cameras on the grounds that they destroyed the value of all the storefront one-hour photo places the city used to have?

June 24, 2011

Congress Still Doesn't Want To Control Foreign Policy

Today's Libya votes were a great example of what I've been trying to say about executive authority and warmaking power. The operation in Libya seems to be unpopular, and President Obama's legal theories about its conduct are held in little esteem by most lawyers, so a majority of House of Representatives members voted to express their disapproval of it. Then when the time came to vote on a resolution that "would have cut off funding for American forces that are not engaged in support missions within the NATO-led coalition, like aerial refueling, reconnaissance, and planning," they reversed course and left the President with a free hand to keep doing what he wants.

And this, it seems to me, is the real story of presidential power over warmaking. It's not so much that we have executive branch power grabs as it is that congress pretty consistently fails to use the leverage that it actually has. Someone who was really determined to block the war in Libya could make an end to the bombing a condition of supporting a debt ceiling increase. When in the seventies congressional majorities were possessed of a strong and sincere desire to restrain Gerald Ford's conduct, they turned out to have a lot of ability to do so. And members of congress have always had a good success rate fighting and winning battles to keep military bases open, keep favored defense contracts flowing, etc. It's just that to win a political fight, you need to really care.

The Oily Trade Deficit

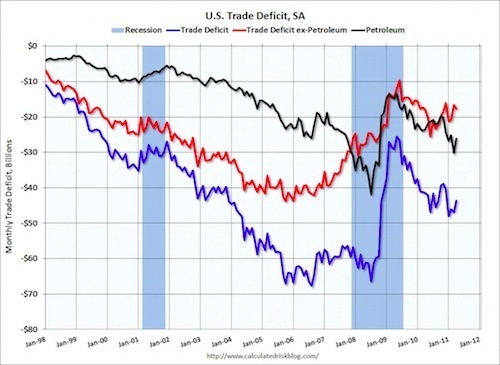

Something that I think still doesn't get enough attention as a big picture cause of the financial crisis is the fundamental weirdness of having so much savings flowing uphill from poor, fast-growing countries into the rich, mature economy of the United States. It ought to be the case that people in fast-growing countries are eager to consume more than they produce, knowing that they'll be much richer in the near future. And it ought to be the case that people in rich countries are eager to invest in poor ones seeking higher returns. But it's not what was happening pre-crisis and it's not what's been happening post-crisis. You can see this gap illustrated by looking at the trade deficit:

What's interesting here is that when you follow Calculated Risk and decompose the trade deficit into oil and not-oil, you do see a change since the height of the recession. Specifically, our not-oil deficit has narrowed considerably, but the dollar value of our oil imports has gone up. Over the long term, we need to rebalance global trade flows to get the whole world to where it needs to be. And high levels of oil consumption make that extremely difficult. To be an overall net exporter, we'd need a really giant surplus in non-oil.

Possible American Development Paths

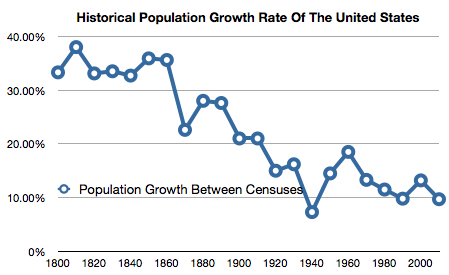

Something that's been interesting to me as I've read about America in the 19th century is how different attitudes toward trade and immigration were back then. These days, of course, we don't have 100 percent no barriers to trade, but we're very very very open to imports of foreign manufactured goods. By contrast, our immigration laws, though liberal by global standards, are incredibly restrictive compared to the open borders regime that prevailed before World War I. Consequently, the population growth rate of the 19th Century United States was staggeringly high:

It's interesting to think about what would have become of the country had we spent our first century or so pursuing the modern consensus view that trade should be more-or-less free but borders open to immigration would be politically unrealistic and unthinkable. The answer, presumably, is that at least initially the country would have been really really rich. The low tariffs would have substantially boosted real purchasing power. They also would have impeded the development of American industry. But that wouldn't have mattered, since given a much lower rate of immigration the ratio of land to workers would have been extremely high. So you'd have a rich, sparsely populated country with an economy geared toward agriculture and natural resource exploitation. Something that looked a lot like Canada or Australia, in other words, rather than the industrial dynamo we became.

I wonder if continued industrialization in Asia means this will be our fate anyway. Over time, the very densely settled triangle between Pakistan, China, and Indonesia that contains about half the world's people should be the "core" of the world economy, with North America looking sparsely settled and resource-rich.

Evolving Troop Levels In Iraq And Afghanistan

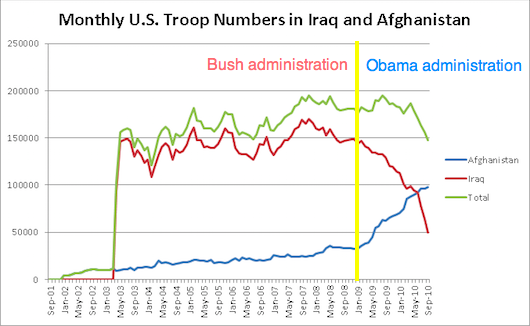

On a more sober note than my annotated version of the White House troop level chart, this shows the evolution of US policy over the past 10 years:

As you can see, there's a quite sharp inflection point associated with President Obama's inauguration as he set about fulfilling his campaign promise to withdraw from Iraq and beef up our presence in Afghanistan. In terms of net soldiers serving abroad in wars, that's meant that the average scale of deployment has been higher than the Bush average. But the current trend is sharply down.

Maine's High-Risk Insurance Pool Has 14 People In It

The Affordable Care Act's high risk insurance pools — which serve as a bridge of coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions until the exchanges are established in 2014 — have had a hard time attracting beneficiaries across the country, but Maine's program is truly struggling. According to the Portland Press Herald, "only 14 people have subscribed to the plan."

Don't Underestimate The Possibility Of Catastrophe

John Dickerson has a Slate piece out that will probably seem wise a few months from now, encouraging everyone not to pay too much attention to the debt ceiling drama, assuring us that what's happening "is simply the drama necessary to advance the story."

And he's probably right. Still, I do continue to be made nervous by Juan Linz's 1990 point (PDF) that "the only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States."

He explained American exceptionalism thusly:

But what is most striking is that in a presidential system, the legislators, especially when they represent cohesive, disciplined parties that offer clear ideological and political alternatives, can also claim democratic legitimacy. This claim is thrown into high relief when a majority of the legislature represents a political option opposed to the one the president represents. Under such circumstances, who has the stronger claim to speak on behalf of the people: the president or the legislative majority that opposes his policies? Since both derive their power from the votes of the people in a free competition among well-defined alternatives, a conflict is always possible and at times may erupt dramatically. There is no democratic principle on the basis of which it can be resolved, and the mechanisms the constitution might provide are likely to prove too complicated and aridly legalistic to be of much force in the eyes of the electorate. It is therefore no accident that in some such situations in the past, the armed forces were often tempted to intervene as a mediating power. One might argue that the United States has successfully rendered such conflicts "normal" and thus defused them. To explain how American political institutions and practices have achieved this result would exceed the scope of this essay, but it is worth noting that the uniquely diffuse character of American political parties—which, ironically, exasperates many American political scientists and leads them to call for responsible, ideologically disciplined parties—has something to do with it.

Since 1990, America's political parties have become substantially less diffuse and we've evolved in the direction of responsible, ideologically disciplined parties. And yet we still have political institutions that have failed almost everyplace else they've been tried. Probably the debt thing will work out for the best. But I'm nervous.

Assessing Barack Obama's Operational Stance On Marriage Equality

As the cause of marriage equality has become steadily more popular, President Obama's unwillingness to embrace it stands out like a bit of a sore thumb. That's especially true because many people agree with David Remnick (via Ta-Nehisi Coates) that Obama's stance on this issue was driven by political fear given the exigencies of the 2008 election. I participated in a 2007 off-the-record chat with Obama during the 2007 edition of Netroots Nation in Chicago that strongly left me with the impression that Obama's view on the subject was purely tactical: Marriage equality campaigners were, in his view, being politically counterproductive for the larger cause of LGBT rights.

But whatever lurks in Obama's heart—see his timeline of shifting stated views if you want to confuse yourself—it's worth noting something here. There are a number of important issues — comprehensive immigration reform, carbon pricing, card check unionization — where Obama has a stated position on the progressive side but there's no clear operational path by which the administration's activities will lead to its stated goals. On marriage equality, it's exactly the reverse situation. Obama is "against" it. But his administration has put forward a legal theory about the unconstitutional of the Defense of Marriage Act that plainly implies that marriage discrimination writ large is unconstitutional. What's more, he's appointing Supreme Court justices who presumably agree with his legal philosophy. It's plausible that some day in the near future, Justice Kennedy will vote with the four progressive justices and act on this principle of anti-discrimination. It's also plausible that if Obama is re-elected that either Kennedy or Justice Scalia (both of whom were born in 1936) will step down and be replaced by a pro-equality Obama appointee.

None of that changes the fact that today is always a good day to do the right thing and stand up for justice. And Obama's nominal opposition creates a talking point that equality opponents can use in their own arguments. Still, it's worth noting that there's a pretty clear path by which Obama's political success leads to victory on marriage equality in a way that's not actually true for other issues that he's embraced more explicitly.

Testing And Content Aren't Enemies

Camden, NJ

Dana Golstein steps up to the plate and offers a partial answer to my question of how Diane Ravitch would run a school district:

This past Monday, Ravitch tweeted the following: "I wish KIPP would take over a complete urban district so people would stop suspecting them of skimming, attrition." This gives a hint as to what Ravitch would do if she were an urban superintendent. She respects KIPP's focus on providing disadvantaged students with a traditional academic curriculum and a structured day, but she is curious to know if the high achievement that follow are transferable to all poor children, not just the ones whose parents are motivated enough to enroll them in a lottery.

I think that as a superintendent, Ravitch would hire principals who really care about what students learn in a history lesson, which books they read in English class, and whether they learn to play a musical instrument. She'd be less concerned with student test scores than with portfolios of their writing. She would would want children to memorize poetry (Auden is Ravitch's particular favorite), learn to make oral presentations, and internalize the rules of grammar and syntax.

On June 18, she tweeted, "I know many think grammar unimportant, but I think it made me a better writer and has stayed with me always." She also wrote, "I was lucky to go to public school in an age without standardized, multiple choice tests. We were graded by written work and oral reports."

This is interesting stuff. I, too, would be interested to see what would happen if KIPP was allowed to take over an entire school district to manage. Presumably, you'd want to give them a relatively small, low performing, high poverty urban district. Someplace like Camden, New Jersey. Clearly, though, implementing KIPP management practices would violate numerous elements of any existing public school collective bargaining agreement. It seems to me that if Ravitch were to actually become New Jersey Education Commissioner and attempt to implement this idea, she'd no longer be the teacher's unions' favorite education historian.

The point on content versus testing seems to me to be a case of talking past each other. I, too, went to a K-8 school where there was a lot of focus on memorizing poetry, learning to make oral presentations, and drilling on grammar. But I also, as it happened, took a lot of standardized tests. I took the Hunter College High School admissions test in 6th grade, I took the New York Specialized High School Admissions Test, I took the SSAT, and I took various state-mandated assessments. And guess what? I did really well on the language arts portions of these tests just as I continued to do really well on the language arts sections of the PSAT, SAT, AP English Language, AP English Literature, and LSAT tests down the years. Why's that? Well I think it's in part because the kind of content-rich curriculum that Ravitch and I both enjoyed is an effective means of teaching kids to understand the English language.

Obviously standardized tests aren't an infallible guide to assessing student achievement. But this is a big country, and there are a lot of situations in which it's useful to compare across different classrooms, different schools, different cities, etc. The only way to do that is with some assessments that are standardized. There's an interesting and important pedagogical issue about what classroom methods do the best job of teaching kids to read and write competently. But it's going to be very hard to develop any evidence about which methods are sound and which teachers are good at implementing them unless we have standardized data about student achievement.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers