Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2264

June 24, 2011

Anything The Executive Branch Can Do, Congress Can Try To Block

As the left has grown increasingly frustrated with inability to make headway on key points in Congress, a cottage industry has sprung up of trying to identify steps the Obama administration can take unilaterally. One such front that I heard a lot about at Netroots Nation was immigration and deportations, where Obama can obviously use his authority as chief executive to slow the pace of deportation, exercise various kinds of discretion, etc. So far, immigration reform advocates haven't made a ton of headway with the administration on this point, but they have gotten some traction on the idea that people shouldn't be deported back into dangerous situations.

But of course nothing is ever truly beyond the reach of congress, and Elise Foley reports that Rep Lamar Smith is working to roll back this limited discretion:

The bill is a political attempt to push back on Democrats, who are advocating for the president to end some deportations since major immigration reform remains nearly impossible. Although the HALT Act is unlikely to make it out of the House — and would almost certainly be vetoed if it passed the Senate — Smith is highlighting a controversial presidential power at the same time that Democrats urge Obama to use it, which may lead him to not assert his authority at all.

Democratic lawmakers have asked the president to use his executive power to stop certain people from being deported, such as families of U.S. service members and citizens, or young men and women attending college in the United States. Some have argued the government should redefine "extreme hardship," a classification used when determining whether a family member or spouse of an American citizen can remain in the United States, to allow families to remain together.

But Smith claims in a "Dear Colleague" letter that the White House is already using its discretion to avoid enforcing immigration law.

This is just a kind of reminder that the American system doesn't, in fact, lead to clearly delineated spheres of "separated" powers. There are, instead, complicated forms of interplay between them and what actually happens depends a great deal on how bold different actors are in using the different levers available to them. House Republicans seem inclined to be extremely bold in their use of congressional authority, while the Obama administration has from day one done a poor job of deploying their executive assets to maximum effect.

U.S. Blowing Higher Ed Export Opportunity

By Matthew Cameron

With immigration back in the news, it's appropriate that USA Today ran an article yesterday highlighting the consequences of policies that make it difficult for hard-working, high-skill individuals to enter the nation legally:

Cost, distance and lingering fears about visa denials in the post-9/11 era have helped make the USA less attractive to foreign students, threatening a lucrative market that is a source of brain power and diversity for U.S. colleges. [...] From 2000 to 2008, the number of students enrolled in a college outside their home country soared 85% to 3.3 million. During that time the U.S. share shrank, from 24% to 19%, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operative Development.

This is bad for all of the obvious reasons: ambitious foreign-born students have their hopes dashed, American universities risk becoming more homogenous and the overall quality of the nation's student population suffers. But as the article points out, there's a seriously negative economic aspect of this situation as well:

Between tuition and living expenses, they [foreign students] contributed $20 billion to the U.S. economy last year, making higher education among the nation's top service exports. Those who return home after graduating help build a better business environment for U.S. companies, says Sánchez, whose office also has organized recent international missions for the aerospace, water technology and beauty and cosmetics industries.

The U.S. still has the best colleges and universities in the world. In this sense, higher education is like information technology or any number of high-skill services in which the nation specializes. It would be absurd for the U.S. government to erect barriers preventing U.S. companies from providing IT services to foreign firms. Doing so would inhibit the growth of foreign economies and deprive U.S. IT companies of revenue. Similarly, it's a really poor idea to make foreign-born students jump through hoops in order to attend U.S. universities. They are denied the opportunity to buy the high-quality educational services they desire, and U.S. universities lose out on revenue that could be reinvested toward providing an even better educational product. The U.S. economy suffers in the long term, as well, since foreign-born students would be able to produce high-value goods and services if they were to remain in the country upon graduation. Alternatively, they could return home with higher earning potential and a greater likelihood to demand U.S. goods and services. For whatever reason, though, policymakers have decided it's preferable to limit these individuals' access to U.S. higher education.

A Debt Ceiling Plaintiff With Grounds To Sue: Credit Default Swap Buyers

I've been sympathetic to the view that if Barack Obama were to simply sweep aside the debt ceiling, arguing that Congress has already appropriated funds and citing Section 4 of Amendment XIV on the validity of the public debt, that nobody in practice would have standing to sue and stop him. But Matt Zeitlin's article making the case that he should do this has actually talked me down somewhat from that view. There is, after all, the matter of the credit default swap holders:

Leaving Congress aside, it appears the only possible party to a suit challenging the administration's ability to exceed the debt ceiling would be a character that almost seems designed to elicit zero public sympathy: those who purchased credit default swaps which would pay off in the event of government default. Charles Tiefer, a law professor at the University of Baltimore, told me that Congress could pass a statute that strengthened the ability of this group of investors to sue as an injured party. But this statute, of course, could be filibustered in the Senate or vetoed by the president. Moreover, it would force Republicans to defend the right of those who had hoped to profit from a national default or dip in creditworthiness to sue the government because their payouts had been prevented.

It's true that this wouldn't be a very sympathetic group of plaintiffs, but that doesn't mean they'd lose. What's more, beyond the specifics in the case I think the general principle that the president shouldn't sweep aside decades of practice and declare the debt ceiling non-binding would generate plenty of sympathy.

The right strategy here is payment prioritization. Keep paying creditors, keep paying transfer programs to the poor, but start paying what the government owes to contractors, health care providers, and state governments in the form of IOUs. Then these unsecured and unwilling creditors become a lobby for raising the debt ceiling so they can get paid.

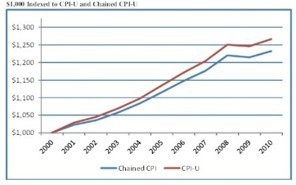

Mysteries Of The Chained CPI Explained

Ezra Klein says that one deficit reduction measure under consideration is to start using the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Chained Consumer Price Index (C-CPI-U) to index Social Security benefits and tax brackets, rather than the current indexes. This is appealing, I guess, because it's simultaneously a benefit cut and a tax hike but you can claim that it's just a technical change. Sadly, though, Ezra seems to think that explaining what it actually is would be too terrifying, saying that "[b]ecause I'd like at least a few readers to get to the end of this post, I'll omit the gory details."

I don't actually think the details are all that gory.

Or, rather, calculating any cost of living index is a fairly gory business that involves lots of people running all around the country writing down the price of various things. And I also find the difference between the CPI-U (used for tax brackets) and the CPI-W (used for Social Security benefits) to be pretty obscure. But the difference between C-CPI-U and old school CPI-U is pretty easy to explain. Simply put, the current index assumes that if the price of beef skyrockets, then consumers just face a higher cost of living in the form of expensive beef. The chained index, by contrast, assumes that beef is a sub-element of a larger "meat" product category such that if beef gets more expensive consumers will respond in practice by buying more pork. Consequently, while the higher price of beef does push up the cost of living, on the chained view it doesn't push it up as much as it would under the unchained view.

Whether this is technically "correct" or not strikes me as a somewhat metaphysical dispute not amenable to any kind of real resolution. It's of course true that if beef rockets up in price, people will respond by buying more pork. But beef isn't pork. We could eat nothing but rice and beans all day, but the fact that we don't have to is part of what makes it nice to live in a non-impoverished country. The important thing about inflation indexing as applied to Social Security is that in practice old people consume much more health care than average people, and old people also tend to be relatively uninterested in high-tech gadgets. This mismatch between the consumption patterns of the elderly and economy-wide trends is much more significant than the chaining issue. On the tax side, however, one of my fondest hopes would be to eliminate the inflation indexing of the brackets altogether so anything that cuts the index rate to a lower level would be welcome.

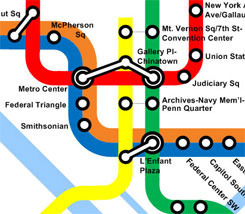

Hard To Build More Core Capacity Unless You Want More Buildings Built In The Urban Core

Eric Fidler's point about the desirability of adding capacity to Metro's core rather than just building more suburban spurs. But like with everything else in DC, this goes back to the question of density in the urban core. A sentence that starts with "if we built more transportation capacity in the urban core…" needs something to go next. If we did this separated Yellow Line proposal, then what would happen? Absent revision of the Height Act, you'd have the exact same quantity of office buildings and office jobs in the areas served by the new line as you have today. A lot of money would be spent, and at the end of the day the city would basically look the same as it does now.

And the same goes for most of the proposals I've seen for extra core capacity. A separated Blue Line that stops in Georgetown, the West End, the Atlas District, etc. sounds great to me. But does that mean more people will be living in Georgetown? More people working in the West End? Will we start allowing 10-story buildings along H Street NE?

To my way of thinking, it's easy to justify the expense of new subway tunnels in the District in order to facilitate big increases in density. Land in DC is very expensive. It should be built up very densely. But to make dense development feasible, it's extremely helpful to have a heavy rail system that can move huge quantities of people. It's a simple, compelling argument. But absent the increase in density, it's a huge expense with relatively narrow benefits.

June 23, 2011

How To (Temporarily) Survive a Debtpocalypse

Intra-caucus dynamics on the GOP side seem to be dooming the debt limit talks. Eric Cantor's preference is for John Boehner to sign a deal he can grumble about, so that when the GOP loses seats in 2012 he can challenge Boehner for the leadership. Boehner, meanwhile, doesn't want to sign a deal that Cantor won't sign. Consequently, we can't get a deal.

This, then, returns us to the subject of tactical modalities available if the country runs up to the debt ceiling. The key issue at this point becomes the fact that hitting the debt ceiling doesn't force an automatic default or a government shutdown. Revenue continues to come in to the federal government. There's simply a gap between how much comes in and how much the government is supposed to spend. The first step to sound policy in this case is to make sure we keep paying interest on the debt. Thus default and immediate catastrophe is avoided. Second, what you want to do is minimize the impact on government activities. That means that in the first instance you want to try to stiff people to whom the government owes money but who will probably keep working even if you don't pay them. Take defense contractors, for example. If Robert Gates tells a bullet-making company that he can't pay the Pentagon's bills this month because Eric Cantor is being obstinate, but please keep sending bullets anyway, the bullet-makers aren't going to leave our troops bullet-less. We just need to tell them to keep sending the invoices coming, and promise that all bills will be paid once Cantor relents. Hospitals, doctors, and other Medicare providers are the other low-hanging fruit here. Patients will continue to be treated, doctors will keep filing paperwork, and Kathleen Sebelius will keep reassuring people that they'll be paid when the congressional gridlock is resolved.

Over time, of course, these tactics tend to run into limits. We may need to start paying people less than their full Social Security checks, mailing a partial benefit plus a note explaining that back benefits will be paid once congress lifts the debt ceiling. My intuition is that various government contractors, doctors, hospitals, etc. will put enough pressure on congress to break the deadlock before these Social Security notes need to start going out. But in political terms it's a very winnable fight for the White House, and in substantive terms doing it this way should minimize impact on the nation's credit.

Running For Vice President Is A Good Way To Become President

I'm in thinking there's nothing in the GOP primary rules to bail Jon Huntsman out from the basic fact that Republican primary voters want someone who's more consistently rightwing than he is.

That said, I've been thinking about the oft-repeated contention that Huntsman is "really running for vice president." The problem with this is that I'm not sure how you go about doing it. But if you can make it work, this looks to me like a pretty good way to become president. In the post-WWII era we've had Barkley, Nixon, Johnson, Humphrey, Agnew, Ford, Mondale, Bush, Quayle, Gore, Cheney, and now Biden as vice presidents. From that list, Nixon, Johnson, Ford, and Bush became president and Humphrey, Mondale, and Gore became major-party presidential nominees. And it seems to me that if Joe Biden wants to be the Democratic nominee in 2016, he probably will. The problem for Huntsman is that we seem to be undergoing a shift in norms with Cheney and Biden, where the idea for a VP pick is to choose somebody boring and senior who's supposed to provide ballast, Washington experience, and a lack of further political ambitions.

Would Shimon Peres Apply His Critique Of Foreign Aid To America's Largest Aid Recipient?

I'm interested to learn, via Alex Tabarrok, that Shimon Peres is a skeptic about foreign aid:

Look, the West can't help everyone and the regimes would be insulted if we tried. But they don't need our help. The greatest poverty in our time has been in China and India. Did these countries reduce poverty because of our help? No. They did it themselves.

Giving is problematic. We take money from poor people in rich countries and give it to rich people in poor countries. Aid sometimes creates corruption.

As Andrew Gelman observes, there's some pronoun weirdness happening. They don't need "our" help? Israel isn't a major source of foreign aid money, rather, according to the Congressional Research Service (PDF), it's "the largest cumulative recipient of U.S. foreign assistance since World War II" and unless you count Iraq continues to be the largest recipient of aid money in annual appropriations. The U.S. doesn't make a ton of friends internationally by subsidizing Israel so heavily, so it's mighty strange to see the president of Israel running around knocking the whole concept. Does he think we should cut the money off? That would be an interesting development, to say the least.

Making Food Affordable By Giving Money To Poor People

By Matthew Cameron

Amid seemingly nonstop news about volatile food prices and political instability in the developing world, here's an encouraging reminder that progress is being made in the global fight against hunger:

The world's top honor in food and agriculture this year goes to two former presidents who led dramatic reductions in hunger and poverty in their countries in the past decade. Ghana's President John Agyekum Kufuor and Brazilian President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva have received the World Food Prize for what the prize citation called "visionary leadership" in reducing poverty and malnutrition.

At a ceremony at the State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development chief Rajiv Shah said they demonstrate an important fact about fighting hunger. "As much as the scientists need to work at it, and as much as we need support from so many agricultural experts, at the end of the day political leadership at the highest levels makes the biggest difference," Shah said.

Indeed, the best thing about these countries' success stories is how straightforward they are. After all, the centerpiece of Ghana's food aid initiative is nothing more than a school lunch program designed "to provide children in public primary schools and kindergartens with one hot nutritious meal, prepared from locally grown food stuffs on every school going day." As for Brazil, its Zero Hunger program is based on cash grants that are given to low-income mothers in exchange for sending their kids to school. That's all it takes — local food for schoolchildren and money for poor people. Perhaps the U.S. government, one of the World Food Prize's sponsors, should take note and quit pretending that its backwards system of agricultural subsidies is necessary for providing citizens with affordable access to food.

The other sad irony here is that while the U.S. is rewarding Ghana and Brazil for their commitment to school lunches and direct aid to the poor, Republicans in Congress are attempting to decimate the domestic versions of those initiatives. The justification for this approach is the old conservative trope that says because we live in a resource-constrained world we can't devote so much money to helping the poor. The fact that countries with a fraction of our GDP have made hunger alleviation a key priority for their governments, however, really exposes the fraudulence of that argument.

What Does Diane Ravitch Think We Should Do To Improve Education In The United States?

Dana Goldstein profiles Diane Ravitch, the distinguished education historian who after a long career as a "reformer" did a full about-face five years ago and has become the teachers union's favorite education pundit. My problem with Ravitch, and the general Ravitchian worldview, is that no matter how many things she writes or how many profiles I read, I can't really figure out what it is she thinks we should do. I know who Ravitch doesn't like (Michelle Rhee, Bill Gates) and I know who she feels is unfairly scapegoated (teachers unions) and I know what she thinks is overhyped (charter schools), but I have no idea what she would do if she were in charge of the education department of an American city.

Consider:

Once a vocal proponent of No Child Left Behind, charter schools, vouchers, and merit pay for teachers, Ravitch decided sometime around 2006 that there was actually no evidence that any of those policies improved American education. She now believes that the "corporatist agenda" of school choice, teacher layoffs, and standardized testing has undermined public respect for one of the nation's most vital institutions, the neighborhood school, and for one of society's most crucial professions: teaching.

The best way to improve American education, the post-epiphany Ravitch argues, is to fight child poverty with health care, jobs, child care, and affordable housing.

I certainly favor all those things, and write extensively on the health care, jobs, and affordable housing issues. Probably I should write more about child care. But I'm a generalist political pundit. How is this point relevant to the job of a person who's in charge of running a school system? I can think of one way. Chancellor Ravitch might show up at a budget committee hearing and ask for more money to run the school system with. Someone might ask why the school system needs more money. Chancellor Ravitch might reply, "No no education is really important." And then the budget committee chair might strike back with, "Sorry, the best way to improve education is to fight child poverty with health care, jobs, child care, and affordable housing." There's an actual fiscal tradeoff between spending money on schools and spending money on non-school social services. But I don't think Ravitch favors reducing school spending. Certainly cutting school spending would be a strange way to express respect for schools and teaching.

Or take her criticism of Teach For America:

Ravitch — who says she'd probably apply for TFA if she were leaving college today — nonetheless thinks that instead of letting the much-publicized program suck up all the "psychic energy," there should be college loan forgiveness for people who become teachers. "Then you would have so many people applying to join this field that you could select the top 10 or 15 percent," she says.

Why would you think that there's a tradeoff between the "psychic energy" expended on TFA and loan forgiveness for public school teachers? Note that the United States already has a loan forgiveness program for public school teachers. Many states have additional programs. So it's a bit odd as a signature policy proposal. But you could make this more generous. The objection, obviously, would be that doing so would cost money. You'd need to raise taxes, which is tough, or cut some other spending. So how do you make the case for raising taxes to make loan forgiveness for teachers more generous while running around telling people that the best way to improve education is to fight child poverty with health care, jobs, child care, and affordable housing? If recruiting better teachers isn't the best way to improve education, then why are we talking about doing more to recruit good teachers?

And again, to return to my initial point, if Ravitch is running a city's school system, she doesn't have it in her authority to alter federal student loan policy. She doesn't have the authority to improve the macroeconomic situation. She doesn't have the authority to change the health care system. So how does she run the school system? What does she do?

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers