Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2261

June 27, 2011

Voters Love The Military

Gallup came out with the latest version of its confidence in institutions poll, the kind of survey that I think sheds more light on real public opinion dynamics than do polls on "the issues":

[image error]

This kind of thing is why it's hard to cut the defense budget, even though voters seem relatively friendly to the idea of cutting the defense budget. No member of Congress in a tough race wants to be in a fight with a general in a country where people have enormous confidence in generals and almost no confidence in Congress. I also think it's interesting that people have much more confidence in the U.S. Supreme Court than they do in other branches of government that are sometimes said to have more democratic legitimacy. The hurly-burly of active participation in actual politics may, in practice, serve to be delegitimizing. Operating in secret, wearing uniforms or robes, and staying above the fray seems to be the road to respect.

Pakistan Falling Behind India Despite Decent Growth

Something I didn't realize until this weekend is that Pakistan was, quite recently, a richer country in per capita than its larger neighbor India. But over the past decades that has changed. Pakistan has put up decent growth numbers, but India's have been better and it's now the substantially richer country as well as a much larger one:

I don't like to spend too much time playing fake South India expert, but it seems to me that if you're a responsible leader in the Pakistani security forces, this trend is going to be your overwhelming concern. Pakistan is weaker than its key regional rival, and the gap is growing. Policy toward everything else — Afghanistan, Osama bin Laden, whatever — is going to take a back seat.

Five Reasons Why Romneycare Is Working

The Boston Globe is out with the second installment in its series examining Massachusetts' landmark 2006 health care reform law. Part one explored Mitt Romney's role in shaping the measure and part two makes a pretty convincing argument that Romney's signature accomplishment has been successful in expanding access to coverage:

– The percentage of residents without insurance coverage is down dramatically, to less than 2 percent; for children, the figure is a tiny fraction of 1 percent, a state survey shows. These are by far the lowest rates in the nation.

– Many more businesses are offering insurance to employees than were before the law. The fear going in was that the opposite would happen.

– The cost of the changes, while large, has proved manageable thus far, though there are some serious warning signs on the horizon, especially as federal stimulus funds, which have helped defray the cost, run out.

– The plan remains exceptionally popular among state residents — indeed its popularity has only grown with time. There are some unhappy sectors — notably small business owners, who had hoped to see moderating premiums and chafe, in some cases, at the heavy-handed enforcement of the rules by the state. And support for the requirement that individuals obtain insurance is down to a slender majority, a recent poll shows. But there is no significant constituency here for repeal.

– And while health care costs continue to grow at alarming rates, as they have nationally, the consensus of industry leaders and health care economists is that this trend cannot be fairly traced to the makeover but rather to cost pressures baked into the existing health care payment system. Massachusetts does have the highest health care costs in the nation, but it owned this dubious distinction long before "RomneyCare'' was born.

All of this complicates Romney's efforts to backtrack from the law, but it also presents an even larger challenge to Republicans who seek to condemn Romneycare and tout their own "free market" health care accomplishments. The fact of the matter is that when you get past all of the attacks, no other state has been able to dramatically reduce the number of uninsured and increase the percentage of residents in private health insurance. Pawlenty, Huntsman and the rest may be eager to battle it out with Romney on health care, but in doing so, they're asking voters to compare their own meager accomplishments to the Bay State's successful near universal coverage expansion. It's not a very flattering comparison and one that Romney should exploit (if he thinks conservative primary voters care about helping the uninsured).

The Problem Of Persuasion

Reacting to news articles which have made it clear that knowledge of gay relatives was a decisive factor in driving much of the politics behind marriage equality in New York, Ta-Nehisi Coates makes a shrewd observation:

Coming out to your family is a specific trauma that doesn't really translate directly to other groups who've the felt the boot on their neck. If there's a a parallel experience, it doesn't occur to me. As indicated here, it's often the source of great pain.

But it is also the source of great political power. People who seek to ostracize gays, must always countenance the potential for disappearing their very family members. It's not like red-lining black people into ghettos. Homophobes must always face the prospect of condemning their own flesh and blood.

On LGBT equality, you have a virtuous circle. The more egalitarian society becomes, the more people are comfortable coming out. And the more people are out, the wider this circle of sympathy spreads. And an important question is what to do about all the other cases when it's harder to take advantage of this kind of dynamic. The poor are often invisible to large swaths of people merely because they live on the other side of town. So what about the even poorer people who live in Bangladesh or Bolivia? Human sympathy is a tremendously powerful force, but the circumstances in which it can be mobilized are sometimes difficult to find.

Sex-Selective Abortion Is A Story About Sex Selection More Than A Story About Abortion

Ross Douthat writes about the popularity of sex-selective abortions in the third world, a subject he knows makes progressives uncomfortable. His mission is to persuade us that we should see this as a problem of abortions as such, rather than a problem of sex-selection making us queasy or as something whose macro-consequences we worry about. This is done by means of a clever line that references Amartya Sen's classic essay "More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing":

The tragedy of the world's 160 million missing girls isn't that they're "missing." The tragedy is that they're dead.

This seems like an issue we can shed some light on with a not-very-outlandish thought experiment. According to both secular liberals and religious conservatives, a human spermatozoon is not a moral person entitled to our protection. To kill one is perfectly acceptable. And yet male fetuses and female fetuses (and ultimately male children and female children) are distinguished from each other according to whether or not their spermatozoon "father" carries an X chromosome or a Y chromosome. In principle, it's not difficult to imagine scientists developing some kind of medication that a man could take that would specifically target one or the other kind. Take the "girl" pill and you become incapable of fathering male children. Take the "boy" pill and you become incapable of fathering female children.

On joint Douthatian and Yglesian principles, nobody's being killed here. But I think that if we found out that use of the "boy" pill was extremely widespread, this might still legitimately worry us for three kinds of reasons. One is that widespread use of the boy pill would express the inegalitarian idea that men are more valuable than women. A second is that widespread use of the boy pill would reflect the existence of ongoing inequities in society that make it the case that a male child is more valuable than a female child. The third is that there are plausible reasons to believe that even a relatively small gender gap in the population could have problematic macro-scale consequences for society.

As it happens, sex-selective medical intervention overwhelmingly takes the form of abortions. But there are plenty of reasons you might be concerned about the phenomenon that don't have to do with abortion specifically. You can imagine other forms of medical intervention. Or consider Lady Jessica and the Bene Gesserit who, allegedly, are able to control the sex of their babies solely through mental will.

Building More Urban Land

Yesterday afternoon I was tweeting about this insane plan to fill in the East River and replace it with a giant network of highways and parking garages. Obviously if you were going to go to great expense to build additional Manhattan land, the thing to do with it is build buildings on it. Space in Manhattan is very expensive. If you make more of it, you need to fill it up with more Manhattan-esque tall buildings. The other issue here is that in order to keep the shipping lanes to and from the Long Island Sound viable, this calls for digging a giant new canal across Brooklyn and Queens. An even more impractical idea is to drain the Hudson River and then try to divert the flow of water through the Harlem River.

A more reasonable idea, it seems to me, would be to do the reverse of that and drain the Harlem River. It's not usable for shipping at this point because of the bridges, and it's just a small tidal basin so I don't think you'd actually need to divert any water anywhere. Admittedly, this land would be less valuable than what you'd get from the other projects, but it actually seems workable.

It's interesting to me that we don't seem to do these large-scale land creation projects anymore. Look at how much bigger Boston got through landfilling. Not only did that creation of the Back Bay area greatly expand the city, it fundamentally alters the geography of Cambridge, which would be much more isolated from the main city with a giant bay over there instead of a small river.

Taxing Church Land

[image error]

American municipalities generally exempt non-profits from paying property taxes. Then because many non-profits, especially colleges and universities, are actually giant lucrative business enterprises, municipalities often partially claw this back through Payment In Lieu Of Taxes (PILOT) agreements with major local institutions. But now with budgets strapped, a lot of municipalities are putting the squeeze on nonprofits further down the food chain. Erwin DeLeon of the Urban Institute is skeptical of the merits of this approach:

Last month, the town manager of Palmer, Massachusetts, goaded by budget shortfalls and Boston's lead, asked 25 nonprofits, including churches and a youth summer camp, to make annual payments.

What will happen to nonprofits like these that serve the unemployed, homeless, poor, and hungry and run on very tight margins themselves? Payments in exchange for their tax-exempt status will likely put some over the edge. In 2009, half of human service nonprofits froze or cut employee salaries while four out of five drew on scant reserves. Another 21 percent opted to reduce programs and services. So where's the slack to tax?

That doesn't quite strike me as the right mode of analysis. Unlike the federal government, municipalities facing an economic downturn have to operate under a fixed budget constraint. If Palmer, Massachusetts doesn't get more money from its churches, then it needs to either cut back on its own programs and services or else it needs to levy higher taxes on something that's not churches. So the question for Palmer isn't "will higher taxes on churches be bad?" It's "will it be worse than the other available options?" I have no real information on this, but that's the right question.

My bigger picture worry about tax exemption in the urban context isn't about the revenue, however; it's about the distortion in resource allocation. Urban land is a scarce commodity, and structures are valuable fixed assets. If you tax land and structures that are operated as homes and business, but don't tax land and structures that are operated as churches, you end up with more land being used for churches and less being used for homes and businesses than would otherwise be the case. Now if the level of God's affection for a town is determined in part by the square footage per worshipper of devotional space, this is a very reasonable policy. By the same token, if God demands the ritual slaughter of goats, then obviously an implicit tax subsidy for animal sacrifice is a good idea. But the more common view in the contemporary United States is that the key factors are the depth of worshippers' personal relationships with Jesus Christ or else their diligence in seeking out the sacraments. By contrast, it's pretty clear that at the margin the quantity of business activity in a town is in part a function of the square footage available for business purposes. Generous tax subsidies for the ritual slaughter of goats wouldn't just be a source of lost municipal revenue; it would be a waste of goats. By the same token, tax subsidies for church land and church structures seem to me to be a waste of land and structures.

My guess is that politically influential pastors, bishops, rabbis, etc. are going to be inclined to disagree.

Going To College Is Very Valuable

American higher education is not a totally optimal value-proposition, and I think it's fairly clear that there's a healthy dose of waste and inefficiency in the system driving tuition inflation. At the same time, I think it's also fairly clear that one of the main reasons why college administrators have been able to get away with ever-rising tuition and spending a lot of money on things of dubious value (the burgeoning ranks of college administrators, say) is precisely because going to college remains a much better idea than not going to college. So I was glad to see David Leonhardt bring some much-needed pushback against the idea that going to college isn't worth it in his Sunday column.

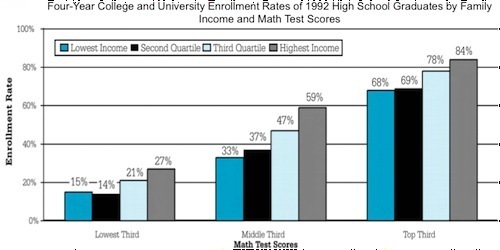

He notes, for example, that the college earnings premium is pretty clearly not just a selection effect: "Various natural experiments — like teenagers' proximity to a campus, which affects whether they enroll — have shown that people do acquire skills in college." With that in view, Peter Orszag's slide about college and class stratification is absolutely crucial viewing:

What you see here is that across the board there clearly is a fair amount of pure selection going on. The smartest kids are most likely to go to college, so it's no surprise that college graduates tend to go on to earn more money even if you're not learning anything of value there. But per Leonhardt, it's clear that on average, people actually do pick up skills in college, and per Orszag, it's clear that among kids of roughly average intelligence, whether or not your parents are rich is a major determinant of whether or not you end up going to school and gaining those skills. This is a big problem. If middle-third kids from families in the bottom half of the income distribution went to college at the same rate as middle-third kids from the top quartile, they'd be better off and we'd have a much more skilled workplace.

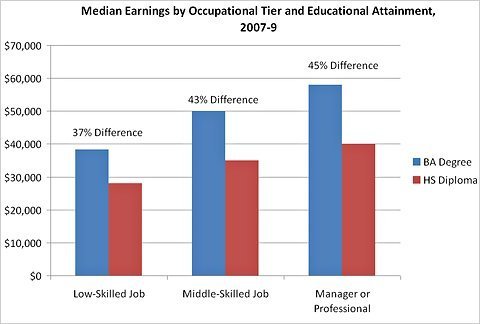

People are sometimes dubious about this at the micro level because they wonder what kind of jobs it is people are doing that they "need" college degrees for. One of the more interesting things I learned from Poor Economics is that in developing countries, increased educational attainment boosts earnings even among near-subsistence peasant farmers who obviously in some sense don't "need" schooling to do their jobs. Leonhardt reports on research indicating that this same mechanism seems to apply to the service economy of modern-day rich countries:

Another study being released this weekend — by Anthony Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose of Georgetown — breaks down the college premium by occupations and shows that college has big benefits even in many fields where a degree is not crucial.

Construction workers, police officers, plumbers, retail salespeople and secretaries, among others, make significantly more with a degree than without one. Why? Education helps people do higher-skilled work, get jobs with better-paying companies or open their own businesses.

Thinking about plumbers, I guess I would say that knowing how to fix pipes is one thing and knowing how to spot and take advantage of business opportunities is another thing. General skills in reading, math, communication, and analytical reasoning are going to help you ply your trade more effectively even if your trade doesn't itself involve much in the way of reading, math, etc. Making it possible for people to gain more skills isn't the be-all and end-all of sound economic policy, but it makes a very big difference especially over the longer-term as the ups and downs of the business cycle even out.

Breakfast Links: June 27, 2011

— Greece has a lot of problems, but per this Guardian editorial the Eurozone is a fundamentally unsound project as currently structured.

— Denmark really doesn't like immigrants.

— Rick Perry's phony economic miracle.

— Nancy Pelosi demands a seat at the table on debt ceiling talks.

— Schumer and Van Holland eye delivery system reform as a way to restrain the growth in Medicare spending.

— Michele Bachmann is in it to win it.

— DREAM on.

— Budget deal may mean defense cuts.

June 26, 2011

The Undersupply of Noisy Mexican Restaurants

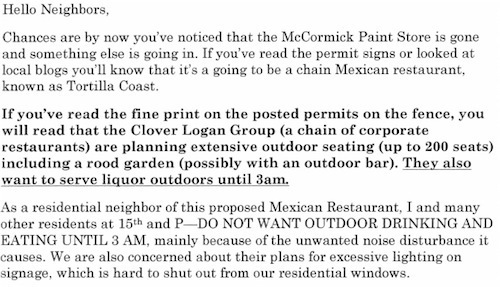

A coalition of NIMBYs living in an expensive apartment building near Logan Circle are upset about a proposed plan to increase business activity in their neighborhood:

It's worth looking at the costs and benefits here. If Tortilla Coast opens, it will presumably be employing people. That's a good thing for those people, and at the margin in general it's good for the earnings prospects of working class people in Washington, DC. What's more, both the income earned by the workers at Tortilla Coast and the sales generated by Tortilla Coast will be taxed by the DC government. That will allow more generous social services or lower tax rates throughout the District of Columbia. And note that the magnitude of these impacts is directly related to the question of how late Tortilla Coast is allowed to stay open, and to whether or not it's allowed to operate an outdoor cafe. Both longer hours and more seats will increase the number of customers Tortilla Coast is able to serve, and thereby will increase the overall volume of employment and sales generated by Tortilla Coast. These are citywide impacts, with citywide implications and it's perverse that the conventional policymaking dynamic treats the question of Tortilla Coast's operating hours as a purely local concern.

Of course it's true that the people living on the block will be more directly impacted by the rest of us. But there's a problem of citywide aggregation here. After all, any proposed new business has to be located somewhere in particular. And even though we might all want less business activity directly outside our doors, we also might all want more business activity citywide. Certainly I think we all claim to want lower unemployment, higher incomes, more generous social services, and lower tax rates and it's difficult to achieve those things without more business activity.

Another thing to consider from a citywide policy framework is that if a noisy Mexican restaurant opens on the corner of 15th and P and people find it unpleasant, it's hardly as if the block is going to become a desolate wasteland. A 1,300 square foot condo on the block in question is currently selling for $780,000. Under the circumstances, introducing a noisy Mexican restaurant to the neighborhood might be considered affordable housing policy. Certainly it's not obvious to me why, as a matter of citywide policy, we would want to put a high weight on protecting the investments of wealthy real estate owners. Progressives have become very interested over the past decade in the ways in which the political system exacerbates inequality but are often a bit negligent when it comes to identifying precise mechanisms. But what we have here on a small scale is an effort to reduce the demand for working class labor in order to maintain elevated asset price values.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers