Kevin Lucia's Blog, page 49

February 24, 2012

The Terror at Miskatonic Falls - Update

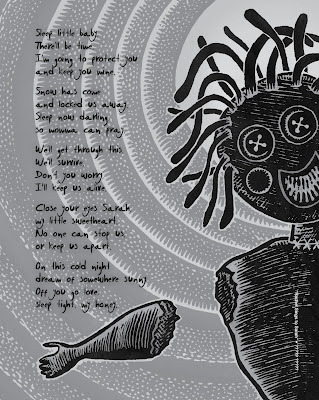

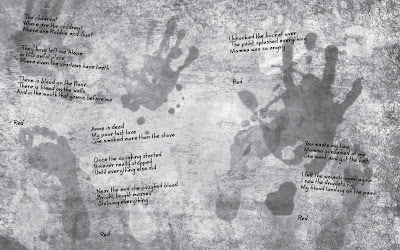

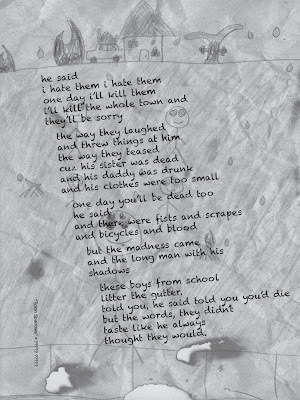

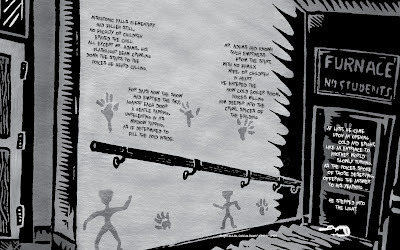

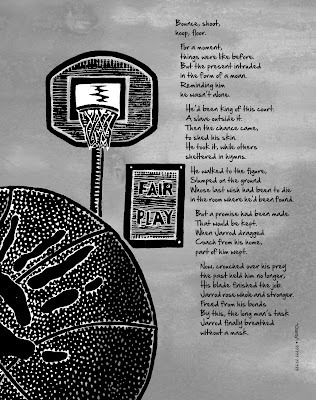

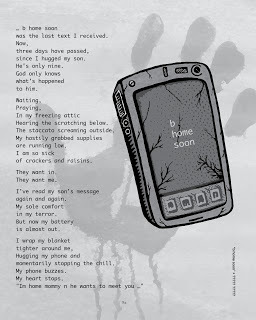

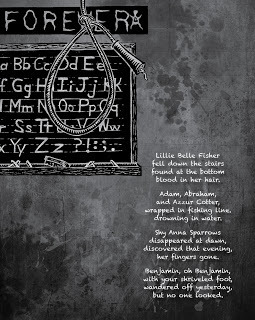

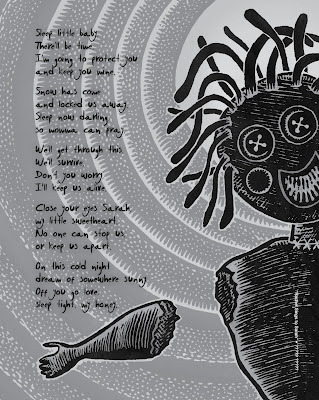

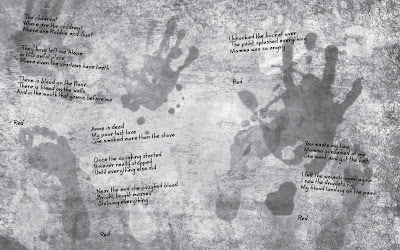

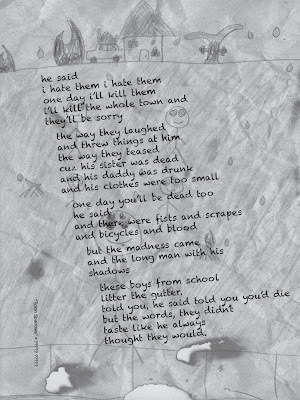

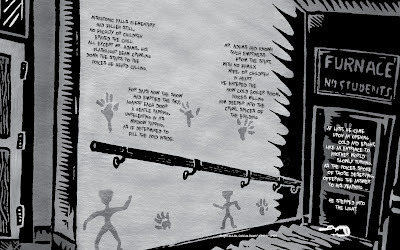

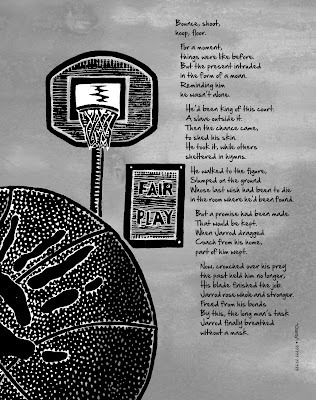

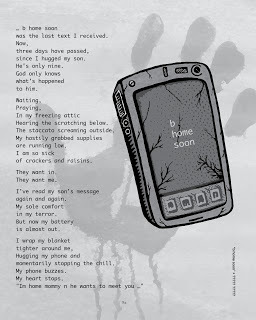

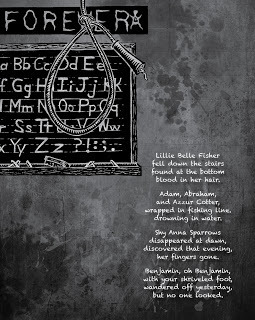

For those new to the blog show around here, allow me to recap the development of The Terror at Miskatonic Falls. It started as a pretty simple idea: basically a collection of Lovecraftian poetry that would be something like Edgar Lee Masters'

Spoon River Anthology

, a collection of epitaph poems from folks in Spoon River whom had all died that served up quirky, humorous, sad, perhaps even....morbid insights into the townspeople's lives.

So an idea was born: a Lovecraftian take on Spoon River, of a small little Massachusetts town next to Miskatonic Falls and the Miskatonic River, where something had been loosed... and all that remained of the townspeople were poems, limericks, even haiku scribbled all over the place: doors, walls, floors....

Submissions and editing took some time. I got lots of poems, and found very quickly that while editing fiction - as I did for Shroud's 2010 Halloween Issue - can be a very cut and dry business for me, either the story "grabs me" by page two or not at all, editing poetry was SO much more involved, taking into accounts all the different forms. Also, I wanted to avoid very OBVIOUS Lovecraftian tropes and images, focusing more on townspeople who were slowly unraveling as they saw dark things flitting to and fro in the shadows.

Danny Evarts - Shroud layout guru - is still working feverishly at this thing. I have to be honest, here, and take most the blame for how long it's taking. Basically, I pitched this project to Tim Deal, he approved it, I collected poems, worked with the poets, then threw it at Danny and said; "Here's this idea I got in my head. Can you, like, do it?"

He's doing an absolutely splendid job. The images continue to come in, and they continue to be lovely. All I know is, I owe Danny a CASE of his favorite beverage when this whole thing is through....

So an idea was born: a Lovecraftian take on Spoon River, of a small little Massachusetts town next to Miskatonic Falls and the Miskatonic River, where something had been loosed... and all that remained of the townspeople were poems, limericks, even haiku scribbled all over the place: doors, walls, floors....

Submissions and editing took some time. I got lots of poems, and found very quickly that while editing fiction - as I did for Shroud's 2010 Halloween Issue - can be a very cut and dry business for me, either the story "grabs me" by page two or not at all, editing poetry was SO much more involved, taking into accounts all the different forms. Also, I wanted to avoid very OBVIOUS Lovecraftian tropes and images, focusing more on townspeople who were slowly unraveling as they saw dark things flitting to and fro in the shadows.

Danny Evarts - Shroud layout guru - is still working feverishly at this thing. I have to be honest, here, and take most the blame for how long it's taking. Basically, I pitched this project to Tim Deal, he approved it, I collected poems, worked with the poets, then threw it at Danny and said; "Here's this idea I got in my head. Can you, like, do it?"

He's doing an absolutely splendid job. The images continue to come in, and they continue to be lovely. All I know is, I owe Danny a CASE of his favorite beverage when this whole thing is through....

Published on February 24, 2012 13:20

February 20, 2012

A Few Movies That Have Scared Me, and Why

I saw Event Horizon in the theaters. Back then, the Internet wasn't as buzzing with trailer sites and I think - if I remember correctly - there was no YouTube, as of then. So, far as I knew, Event Horizon was just the next science fiction flick to hit the big screen.

Boy.

Was I WRONG.

This movie still stands as one of the very few that have genuinely freaked me out. I still struggle to understand why. There's plenty of gore in the end - which actually DID turn me off, a little, because it seemed to lose a lot of it's creepiness at that point - but for 90 % of this film, I jumped at nothing, I shivered and shuddered was afraid.

Of course, the above clip contains a lot for me to connect to. First, of course - operating from my own beliefs of the universe - we have an evil ship that may or may not have gone to Hell and brought something back with it. Nothing like that to get a life-long Protestant's blood pumping and heart pounding. But there was something....more.

It's about the characters themselves, you see. Do I feel for them? Associate with their plight? Feel sympathy for their troubles, feel concern for their welfare?

And by this point of the movie, I'd connected with the main characters, or at least had assimilated - from Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror - their struggles into my perception of them in their situation. And in Event Horizon, we're clearly presented with the main character's traumas before things start getting really wild wooly:

1. Captain Miller (

2. Dr. Weir (

3. Peters, Med Tech (

4. D. J. (

And also, too...Event Horizon features the classic case of hubris, in man over-reaching himself and probing mysteries better left unknown:

Black Hole - It's Perfectly Safe....

The end (spoilers) also is something I'll always react to, personally....and that's the ultimate sacrifice for others: (be warned...a little gore, here)

So ultimately, Event Horizon worked for me, because it hit all the points Carroll lays out for art-horror:

1. invokes feeling of fear for characters, because they were created strongly enough for me to assimilate them and their fears

2. invokes disgust in impure, nightmarish images (that were done very sparingly to begin with, might've be overdone in the end)

And this movie incorporates feelings of "art-dread" by invoking the awareness of avowed, inexplicable forces of the universe (hell, demons), and because we know of Captain Miller's fear of losing anyone else, the pathos of his final sacrifice to save his crew has all that much more impact.

So, let's assume that all the other movies I'll mention hit these same things, so for them, I'll just give brief descriptions, my take on them.

VERY creepy. Very surreal. Had some nice moments. And, I assimilated the main character's confusion and disorientation, felt that way myself. The sequels were fun, but this one stands far above them in the creep factor.

My students think I'm crazy when I say this freaked me out (they say it's lame) but it did. Maybe because of the ending, because we've come to expect the problem in a horror movie to be "figured out". And in this one, we're given a head-fake at the end, but no solution here...

Do I even need to say anything, here? This is the movie the SAW movies desperately want to be.

Before this blog gets ridiculously long, here's a trailer for a movie that's coming up - again, not "horror" - that for some reason just sets me all shivering with dread. Looking forward to this release, definitely.

Seems like I haven't seen a lot of horror movies, doesn't it? Tis true, and I have seen more than these, but these are some of the few that have actually SCARED me. I've connected to quite a few and enjoyed them for different reasons, reasons that perhaps I'll articulate tomorrow or later this week....

Published on February 20, 2012 11:22

The Philosophy of Horror - Mini Review #2, of Chapter 2

Just finished chapter two of Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, (which I'm reviewing and researching for my Film & Philosophy grad class), and he ran through a bunch of theories as to how it is viewers of horror cinema and readers of horror fiction can actually feel emotion, experience what he calls "art-horror" at something that's not real, or could not exist in reality. He ran through a few different scenarios, carefully dismantling them as not holding up very well:

1. The Illusion Theory, or "Suspense of Disbelief":

Here, Carroll deals with the idea that readers/viewers WILLINGLY suspend their disbelief that, say, a giant flood of green slime is coming for them (if that's what they're watching/reading about), and BELIEVE that it's actually coming for them, for entertainment's sake.

The clear problem here, Carroll points out, is that if they ACTUALLY WILL themselves (a hard feat) to believe in the green slime, the level of terror they'd feel would propel them to leave the theater, and be pretty counterproductive to actually enjoying the movie on any level.

This is important, because it strikes a blow at the claim I've heard lots of anti-horror folks level at horror and horror fans: "You're just a sick, twisted individual that loves misery and wants to be scared all the time!" Obviously not true, according to Carroll's conclusions. Yes, the flush of adrenaline during an exciting scene is part of enjoying cinema and fiction, but that's not limited to horror, either. Can find that in action flicks, suspense thrillers, even chick flicks.

2. The Pretend Theory:

Here Carroll cites Kendall Walton's theory of "Pretend Fear". That, like children playing mud pies or Cowboys'n Indians, viewers and readers of horror fiction "pretend" they're afraid, therefore experiencing "pretend" emotions.

Though this sounds plausible, Carroll points out several problems with this as well, saying that first of all, it jumps back and forth over a line dividing intent and subconscious urges - either we actually CHOOSE to pretend belief in something, therefore feeling pretend fear for fun and entrainment, or that, like children who naturally play "pretend", even though we don't acknowledge the rules of "pretend", we "know" them subconsciously, and are adherent to them.

Carroll sees problems with the idea of "pretend fear" being engaged at will, because in his experience viewing movies, this wasn't the case. For several movies, he felt instinctual stirrings of real, genuine, emotional fear. For others, however - perhaps those not as well done - he simply couldn't do it, which seems to invalidate the idea that a viewer can WILL himself to feel pretend fear.

Also, Carroll comes back to another point - if the viewer/reader is "unaware" of the rules on a conscious level, then their "pretend" fear would be indistinguishable from "real" fear, once again undercutting any entertainment value or enjoyment of said movie/book.

One major element that seems to draw audiences/readers to horror cinema/fiction is the following, which he comes back to quite often in the text, our connection to the Protagonists and their fears:

"...We can fear for others....we can fear for the dog that runs into traffic just as we can fear for the fate of political prisoners in countries we will never visit...so might we fear for the lives of fictional characters just as we fear for the lives of actual political prisoners....it can be argued that....we can be moved emotionally not only in terms of fear for others, but by our recognition that something...is fearsome ever if we do not believe it constitutes clear and present danger." (pg. 76)

He bandies about here whether or not emotions require beliefs - whether or not readers/viewers actually HAVE to believe what they see. This leads him to the "Thought Theory", in which he basically states:

"I maintain the practice of fiction - including our emotional responses - is actually built on our capacity to be moved by thought contents and to take pleasure in being so moved"

In other words, even if viewers don't necessarily believe the object of fear exists, if it's been done well enough, simply the thought or concept is enough to produce an emotional reaction. So even if the monster in the movie is not real, the thought of it can produce a real, emotional reaction; and even if these fictional characters are facing fictional dangers, the thoughts of these scenarios can produce real, emotional reactions.

And so he continues on to the next theory:

3. Character-Identification:

In this theory, Carroll posits that many consumers of horror fictions and cinema - as well as critics - cite how well audiences/readers "identify" with main characters of horror films and stories. How well we connect with characters, feel for them, root for them, feel concern for their welfare helps determine how strong or valid an emotional reaction we feel to their plight.

The problem here, Carroll notes, is simply in the title: identification, which to him implies a symmetry between what the characters and the audiences feel, which clearly doesn't make sense. If a monster is descending upon Becky, the audience feels concern for her safety, as well as suspense. Becky, however, is probably too scrambled to think anything other than "RUN!"

Our reactions are different, as well. When we learn that Oedipus has killed his father and slept with his mother - through no fault of his own, through tragic fate - the audience feels sympathy for Oedipus, we feel bad for him (along with a little revulsion, also). However, Oedipus himself feels guilty, self-loathing, and responsible for the deaths of his father and the defilement of his mother.

Also, there's the issue of dramatic irony to consider: that often, the audience knows far more than the main character, and would be experiencing an entirely different set of feelings than the main character, or at the very least, experiencing far more nuanced and specific feelings. For example, maybe Becky very much DESERVES to be devoured by this monster, so while she feels fear, the audience feels justified, or at the very least knows that her own actions have led her to this, and at best pity her.

Carroll ends this chapter, however, really focusing on this element: that powerful connection between the audience/reader and the movie/story's characters. In his estimation, there's an assimilation that occurs - in well-done movies and novels, readers and viewers assimilate the character's situation, come to understand them, their fears, the danger they're in...but still remain outside the character, with all our beliefs and fears and prejudices interacting with this assimilated knowledge - which helps explain why this can be so subjective, why one person will find a movie/situation scary, and another find it laughable.

So, in a rare blogging excess, in a bit I'll post another blog with movie clips from films that have really scared me, and why. Stay tuned...

1. The Illusion Theory, or "Suspense of Disbelief":

Here, Carroll deals with the idea that readers/viewers WILLINGLY suspend their disbelief that, say, a giant flood of green slime is coming for them (if that's what they're watching/reading about), and BELIEVE that it's actually coming for them, for entertainment's sake.

The clear problem here, Carroll points out, is that if they ACTUALLY WILL themselves (a hard feat) to believe in the green slime, the level of terror they'd feel would propel them to leave the theater, and be pretty counterproductive to actually enjoying the movie on any level.

This is important, because it strikes a blow at the claim I've heard lots of anti-horror folks level at horror and horror fans: "You're just a sick, twisted individual that loves misery and wants to be scared all the time!" Obviously not true, according to Carroll's conclusions. Yes, the flush of adrenaline during an exciting scene is part of enjoying cinema and fiction, but that's not limited to horror, either. Can find that in action flicks, suspense thrillers, even chick flicks.

2. The Pretend Theory:

Here Carroll cites Kendall Walton's theory of "Pretend Fear". That, like children playing mud pies or Cowboys'n Indians, viewers and readers of horror fiction "pretend" they're afraid, therefore experiencing "pretend" emotions.

Though this sounds plausible, Carroll points out several problems with this as well, saying that first of all, it jumps back and forth over a line dividing intent and subconscious urges - either we actually CHOOSE to pretend belief in something, therefore feeling pretend fear for fun and entrainment, or that, like children who naturally play "pretend", even though we don't acknowledge the rules of "pretend", we "know" them subconsciously, and are adherent to them.

Carroll sees problems with the idea of "pretend fear" being engaged at will, because in his experience viewing movies, this wasn't the case. For several movies, he felt instinctual stirrings of real, genuine, emotional fear. For others, however - perhaps those not as well done - he simply couldn't do it, which seems to invalidate the idea that a viewer can WILL himself to feel pretend fear.

Also, Carroll comes back to another point - if the viewer/reader is "unaware" of the rules on a conscious level, then their "pretend" fear would be indistinguishable from "real" fear, once again undercutting any entertainment value or enjoyment of said movie/book.

One major element that seems to draw audiences/readers to horror cinema/fiction is the following, which he comes back to quite often in the text, our connection to the Protagonists and their fears:

"...We can fear for others....we can fear for the dog that runs into traffic just as we can fear for the fate of political prisoners in countries we will never visit...so might we fear for the lives of fictional characters just as we fear for the lives of actual political prisoners....it can be argued that....we can be moved emotionally not only in terms of fear for others, but by our recognition that something...is fearsome ever if we do not believe it constitutes clear and present danger." (pg. 76)

He bandies about here whether or not emotions require beliefs - whether or not readers/viewers actually HAVE to believe what they see. This leads him to the "Thought Theory", in which he basically states:

"I maintain the practice of fiction - including our emotional responses - is actually built on our capacity to be moved by thought contents and to take pleasure in being so moved"

In other words, even if viewers don't necessarily believe the object of fear exists, if it's been done well enough, simply the thought or concept is enough to produce an emotional reaction. So even if the monster in the movie is not real, the thought of it can produce a real, emotional reaction; and even if these fictional characters are facing fictional dangers, the thoughts of these scenarios can produce real, emotional reactions.

And so he continues on to the next theory:

3. Character-Identification:

In this theory, Carroll posits that many consumers of horror fictions and cinema - as well as critics - cite how well audiences/readers "identify" with main characters of horror films and stories. How well we connect with characters, feel for them, root for them, feel concern for their welfare helps determine how strong or valid an emotional reaction we feel to their plight.

The problem here, Carroll notes, is simply in the title: identification, which to him implies a symmetry between what the characters and the audiences feel, which clearly doesn't make sense. If a monster is descending upon Becky, the audience feels concern for her safety, as well as suspense. Becky, however, is probably too scrambled to think anything other than "RUN!"

Our reactions are different, as well. When we learn that Oedipus has killed his father and slept with his mother - through no fault of his own, through tragic fate - the audience feels sympathy for Oedipus, we feel bad for him (along with a little revulsion, also). However, Oedipus himself feels guilty, self-loathing, and responsible for the deaths of his father and the defilement of his mother.

Also, there's the issue of dramatic irony to consider: that often, the audience knows far more than the main character, and would be experiencing an entirely different set of feelings than the main character, or at the very least, experiencing far more nuanced and specific feelings. For example, maybe Becky very much DESERVES to be devoured by this monster, so while she feels fear, the audience feels justified, or at the very least knows that her own actions have led her to this, and at best pity her.

Carroll ends this chapter, however, really focusing on this element: that powerful connection between the audience/reader and the movie/story's characters. In his estimation, there's an assimilation that occurs - in well-done movies and novels, readers and viewers assimilate the character's situation, come to understand them, their fears, the danger they're in...but still remain outside the character, with all our beliefs and fears and prejudices interacting with this assimilated knowledge - which helps explain why this can be so subjective, why one person will find a movie/situation scary, and another find it laughable.

So, in a rare blogging excess, in a bit I'll post another blog with movie clips from films that have really scared me, and why. Stay tuned...

Published on February 20, 2012 09:08

February 19, 2012

Does - Can - Horror Really SCARE? Or Does It Only Disgust? Part 1

"Writers who used to strive for awe and achieve fear, now strive for fear and achieve only disgust" - David Aylward

Almost finished with chapter two of Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, (which I'm reviewing and researching for my Film & Philosophy grad class), in which he's trying to identify how and why audiences of horror cinema and readers of horror fiction can actually experience any kind of emotional fear of monsters and plots and situations they know aren't real, and in many cases couldn't exist in the real world.

I'll sketch out those basic ideas tomorrow, but this chapter, especially, has provided lots of food for thought, as a reader and writer. For regular readers of this blog, I'll admit again - I'm probably over-thinking things and splitting philosophical hairs - but I'm basically using the blog to thrash thoughts around about horror cinema and the horror genre in general for a presentation and an eventual paper in my Film & Philosophy graduate class at BU.

Not expecting to reach any grand revelations about the horror genre or why I labor in it, necessarily, but as a writer - even, GASP, an artist - I think it's important to wrestle often with why and how we produce the work we do. And doing it for graduate credit just makes it all the sweeter. So, anyhoo...

Does horror really scare me? If not...then why do I read it?

This chapter of Carroll's work really set me to thinking, as well as a recent vlog post by suspense novelist Mike Duran. Now, Mike was targeting specifically the genre of "Christian Horror", discussing how doctrinal constrictions at Christian publishing houses determine that novels end in certain, predictable ways that may undercut any "scariness" they might have. But it really made me think: when was the last novel that really scared me? (I'll address horror movies tomorrow).

And I had to pause.

Because I struggled to think of a novel that really scared me.

In some ways, it goes back to something Carroll said in chapter one, which set me thinking about what it was that I wrote, what I wanted most to inspire in people. Again, keeping in mind that trying to define and hedge borders around genres is sketchy business, here's what Carroll said that really spun the gears in my brain:

"nevertheless, I do think that there is an important difference between this type of story - which I want to call tales of dread - and horror stories. Specifically, the emotional response they elicit seems to be quite different than that engendered by art-horror. The uncanny event which tops off such stories cause a sense of unease and awe, perhaps of momentary anxiety and foreboding. These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe. Where art-horror involves disgust as a central figure, what might be called art-dread does not" (pg. 42)

By this definition - I most want to write what Carroll calls art-dread, not art-horror. And, in a natural leap, what I READ informs what I write, so most the work I READ falls into the above category, also. (I also like to read and write genre-mixes - see Norman Partridge for my favorite, there - and my current WIP is definitely a genre mix).

Of course, when it comes to how the industry packages horror fiction and film, there's no distinction. It's all just "horror". Charles L. Grant, Ramsey Campbell, T. M. Wright, Norman Prentiss, Mary SanGiovanni, Gary A. Braunbeck, Ron Malfi, Rio Youers, Dan Keohane even T. L. Hines, Travis Thrasher and Dean Koontz (because Peter Straub and Stephen King and Robert McCammon, also my favorites, can kinda do it all)....are all labeled "horror" writers, or writers of "dark fiction"...but their work hinges on - in my experience - more the definition of "art-dread" than "art-horror". This is the stuff I read, I crave, not necessarily because it horrifies me or scares me, but because generally, in my opinion as a reader, their works often...

"are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe."

Of course, certain novels by certain horror writers I enjoy because they do the same thing. For example, I haven't read all of Brian Keene's novels, but the ones I have and have really loved: The Rising, Dead City, Ghost Walk, A Gathering of Crows - have all dealt in these themes. They had the usual trappings of horror, but they deal with those unknown, inexplicable forces of the universe.

But scare? Horrify?

Hmmmm.

According to Carroll's definition, very few novels I've read have achieved the "horrification" (yeah, I sorta made that word up) he talks about. Certainly, several novels have reached the disgust level - won't name any names, but I've definitely read some novels in my time as a reviewer that have turned my stomach - but according to Carroll's definition, that's not good enough, because the work must achieve BOTH.

(are you getting by now how subjective this all is, based on the reader and viewer's preferences....?)

So, again: what novels have really scared me? (Notice: I didn't say disturb or fill me with unease and dread or made me cry or filled me with dramatic tension. I said SCARED ME).

I can only think of two, and ironically enough, it was the combination of real life events with the actual reading of these novels that provided that sense of horror:

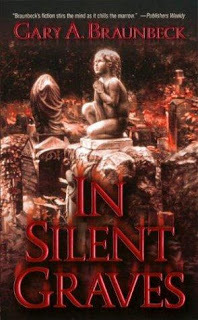

1.

In Silent Graves

, by Gary A. Braunbeck - about a man who loses his wife and unborn child, and all the trauma he goes through (of course, surrounded by supernatural drama and trauma), I read this while my wife visited her sister in Colorado Springs for a week. Any time someone takes a plane these days, the specter of 9/11 looms large. So imagine, me reading this late at night in a dead quiet house with the kids sleeping and my wife several states away, having to return by plane, me counting the days until she was on the ground in New York and safe....reading about a man who'd lost his soul mate....yeah. Some definite shivers of fear, with this one.

1.

In Silent Graves

, by Gary A. Braunbeck - about a man who loses his wife and unborn child, and all the trauma he goes through (of course, surrounded by supernatural drama and trauma), I read this while my wife visited her sister in Colorado Springs for a week. Any time someone takes a plane these days, the specter of 9/11 looms large. So imagine, me reading this late at night in a dead quiet house with the kids sleeping and my wife several states away, having to return by plane, me counting the days until she was on the ground in New York and safe....reading about a man who'd lost his soul mate....yeah. Some definite shivers of fear, with this one.

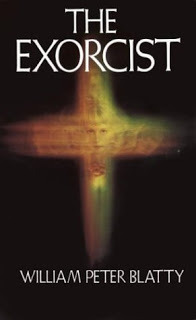

2.

The Exorcist

, by William Peter Blatty. Again, home alone at night, with Abby and the kids over at her parents. Reading this in a dead quiet house out in the country, of course counting my own faith beliefs....yep. This one did the trick, too.

2.

The Exorcist

, by William Peter Blatty. Again, home alone at night, with Abby and the kids over at her parents. Reading this in a dead quiet house out in the country, of course counting my own faith beliefs....yep. This one did the trick, too.

And, believe it or not...that's it. I'm sitting here, thinking there was a third one...but I guess not.

So. Only two novels I've ever read that have actually scared me. All the rest of the horror novels or quiet horror novels or tales of dread or supernatural suspense or thrillers or what-have-you have definitely had what I'd consider to be highly effective, positive impacts - stories about those unknown powers of the universe - but I can only really say those two novels scared me, and because they both struck me HARD, where it hurts most: at family and faith.

Hmmm. There's something there I want to say, something BIG, about the development of society in a post-modern world, the increase of slasher flicks discounting the supernatural, this quote by critic David Aylward:

"Writers who used to strive for awe and achieve fear, now strive for fear and achieve only disgust"

...and what that says about society today, how today's horror films and novels can say SO much about us, spiritually and emotionally and philosophically...but I'm not THERE, yet. Probably never will be, not completely. But hopefully, by the end of the semester - after a lot more reading and studying and blogging - I'll be THERE enough to write my paper, and post some conclusions (of sorts) here.

Tomorrow, I'll look at what kinds of movies scare me. And not all of them are "horror".....

Almost finished with chapter two of Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, (which I'm reviewing and researching for my Film & Philosophy grad class), in which he's trying to identify how and why audiences of horror cinema and readers of horror fiction can actually experience any kind of emotional fear of monsters and plots and situations they know aren't real, and in many cases couldn't exist in the real world.

I'll sketch out those basic ideas tomorrow, but this chapter, especially, has provided lots of food for thought, as a reader and writer. For regular readers of this blog, I'll admit again - I'm probably over-thinking things and splitting philosophical hairs - but I'm basically using the blog to thrash thoughts around about horror cinema and the horror genre in general for a presentation and an eventual paper in my Film & Philosophy graduate class at BU.

Not expecting to reach any grand revelations about the horror genre or why I labor in it, necessarily, but as a writer - even, GASP, an artist - I think it's important to wrestle often with why and how we produce the work we do. And doing it for graduate credit just makes it all the sweeter. So, anyhoo...

Does horror really scare me? If not...then why do I read it?

This chapter of Carroll's work really set me to thinking, as well as a recent vlog post by suspense novelist Mike Duran. Now, Mike was targeting specifically the genre of "Christian Horror", discussing how doctrinal constrictions at Christian publishing houses determine that novels end in certain, predictable ways that may undercut any "scariness" they might have. But it really made me think: when was the last novel that really scared me? (I'll address horror movies tomorrow).

And I had to pause.

Because I struggled to think of a novel that really scared me.

In some ways, it goes back to something Carroll said in chapter one, which set me thinking about what it was that I wrote, what I wanted most to inspire in people. Again, keeping in mind that trying to define and hedge borders around genres is sketchy business, here's what Carroll said that really spun the gears in my brain:

"nevertheless, I do think that there is an important difference between this type of story - which I want to call tales of dread - and horror stories. Specifically, the emotional response they elicit seems to be quite different than that engendered by art-horror. The uncanny event which tops off such stories cause a sense of unease and awe, perhaps of momentary anxiety and foreboding. These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe. Where art-horror involves disgust as a central figure, what might be called art-dread does not" (pg. 42)

By this definition - I most want to write what Carroll calls art-dread, not art-horror. And, in a natural leap, what I READ informs what I write, so most the work I READ falls into the above category, also. (I also like to read and write genre-mixes - see Norman Partridge for my favorite, there - and my current WIP is definitely a genre mix).

Of course, when it comes to how the industry packages horror fiction and film, there's no distinction. It's all just "horror". Charles L. Grant, Ramsey Campbell, T. M. Wright, Norman Prentiss, Mary SanGiovanni, Gary A. Braunbeck, Ron Malfi, Rio Youers, Dan Keohane even T. L. Hines, Travis Thrasher and Dean Koontz (because Peter Straub and Stephen King and Robert McCammon, also my favorites, can kinda do it all)....are all labeled "horror" writers, or writers of "dark fiction"...but their work hinges on - in my experience - more the definition of "art-dread" than "art-horror". This is the stuff I read, I crave, not necessarily because it horrifies me or scares me, but because generally, in my opinion as a reader, their works often...

"are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe."

Of course, certain novels by certain horror writers I enjoy because they do the same thing. For example, I haven't read all of Brian Keene's novels, but the ones I have and have really loved: The Rising, Dead City, Ghost Walk, A Gathering of Crows - have all dealt in these themes. They had the usual trappings of horror, but they deal with those unknown, inexplicable forces of the universe.

But scare? Horrify?

Hmmmm.

According to Carroll's definition, very few novels I've read have achieved the "horrification" (yeah, I sorta made that word up) he talks about. Certainly, several novels have reached the disgust level - won't name any names, but I've definitely read some novels in my time as a reviewer that have turned my stomach - but according to Carroll's definition, that's not good enough, because the work must achieve BOTH.

(are you getting by now how subjective this all is, based on the reader and viewer's preferences....?)

So, again: what novels have really scared me? (Notice: I didn't say disturb or fill me with unease and dread or made me cry or filled me with dramatic tension. I said SCARED ME).

I can only think of two, and ironically enough, it was the combination of real life events with the actual reading of these novels that provided that sense of horror:

1.

In Silent Graves

, by Gary A. Braunbeck - about a man who loses his wife and unborn child, and all the trauma he goes through (of course, surrounded by supernatural drama and trauma), I read this while my wife visited her sister in Colorado Springs for a week. Any time someone takes a plane these days, the specter of 9/11 looms large. So imagine, me reading this late at night in a dead quiet house with the kids sleeping and my wife several states away, having to return by plane, me counting the days until she was on the ground in New York and safe....reading about a man who'd lost his soul mate....yeah. Some definite shivers of fear, with this one.

1.

In Silent Graves

, by Gary A. Braunbeck - about a man who loses his wife and unborn child, and all the trauma he goes through (of course, surrounded by supernatural drama and trauma), I read this while my wife visited her sister in Colorado Springs for a week. Any time someone takes a plane these days, the specter of 9/11 looms large. So imagine, me reading this late at night in a dead quiet house with the kids sleeping and my wife several states away, having to return by plane, me counting the days until she was on the ground in New York and safe....reading about a man who'd lost his soul mate....yeah. Some definite shivers of fear, with this one. 2.

The Exorcist

, by William Peter Blatty. Again, home alone at night, with Abby and the kids over at her parents. Reading this in a dead quiet house out in the country, of course counting my own faith beliefs....yep. This one did the trick, too.

2.

The Exorcist

, by William Peter Blatty. Again, home alone at night, with Abby and the kids over at her parents. Reading this in a dead quiet house out in the country, of course counting my own faith beliefs....yep. This one did the trick, too. And, believe it or not...that's it. I'm sitting here, thinking there was a third one...but I guess not.

So. Only two novels I've ever read that have actually scared me. All the rest of the horror novels or quiet horror novels or tales of dread or supernatural suspense or thrillers or what-have-you have definitely had what I'd consider to be highly effective, positive impacts - stories about those unknown powers of the universe - but I can only really say those two novels scared me, and because they both struck me HARD, where it hurts most: at family and faith.

Hmmm. There's something there I want to say, something BIG, about the development of society in a post-modern world, the increase of slasher flicks discounting the supernatural, this quote by critic David Aylward:

"Writers who used to strive for awe and achieve fear, now strive for fear and achieve only disgust"

...and what that says about society today, how today's horror films and novels can say SO much about us, spiritually and emotionally and philosophically...but I'm not THERE, yet. Probably never will be, not completely. But hopefully, by the end of the semester - after a lot more reading and studying and blogging - I'll be THERE enough to write my paper, and post some conclusions (of sorts) here.

Tomorrow, I'll look at what kinds of movies scare me. And not all of them are "horror".....

Published on February 19, 2012 04:24

February 12, 2012

Interesting Reflections on the Origin of the Horror Genre

Just finished the first chapter of Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, (which I'm reviewing and researching for my Film & Philosophy grad class), and he offers this interesting reflection on the origins of the horror genre.

Just finished the first chapter of Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, (which I'm reviewing and researching for my Film & Philosophy grad class), and he offers this interesting reflection on the origins of the horror genre.Though it's something that can be debated, Carroll marks the middle of the 18th century as the origin point of the horror genre, developing from Gothic novels such as Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764). He doesn't try and make a case as to who wrote the first Gothic novel, just that the major consensus seems that the Gothic novel developed during this time period.

What he finds interesting is that horror's "birth" overlaps the period cultural historians call the "Enlightenment" or "The Age of Reason". This period is thought to have spanned the 18th century, saw the wide dissemination of the ideas of Descartes, Bacon, Locke, Hobbes, and Newton to the reading public (pg. 55).

What he finds interesting is that horror's "birth" overlaps the period cultural historians call the "Enlightenment" or "The Age of Reason". This period is thought to have spanned the 18th century, saw the wide dissemination of the ideas of Descartes, Bacon, Locke, Hobbes, and Newton to the reading public (pg. 55). The Enlightenment, of course, rested on "the immense achievements of natural science", and things like religion or of a supernatural nature were viewed with distrust, because it valued faith and revelation over reason (pg. 55).

And, interesting to both Carroll - and honestly, myself - it is against this backdrop that "horror" found its birth in the Gothic novel, a fiction that was very fixated on the supernatural and "unknown". Carroll offers two hypotheses for this development (both of which he admits are flawed and can be argued against):

1. the idea that the "horror" or "Gothic" genre developed as some sort of "answer" to "The Enlightenment" or "The Age of Reason", a time period marked by reason and science and nature as the end all and be all, whereas horror/Gothic fiction explored emotions, especially violent ones in the case of the main characters. Also, Carroll points out that while a hallmark of The Enlightenment was objectivity, a hallmark of the horror novel is subjectivity (pg. 56).

So, according to this idea, Carroll advances the theory that while a convert of The Enlightenment held a naturalistic conception of the world, the horror novel presumes the existence of the supernatural, at least for fiction's sake. That, in opposition to The Enlightenment's "faith" in progress, horror promoted a regression to a belief in the unseen supernatural, which The Enlightenment had attempted to repress, or at least discourage (pg. 56).

Of course, Carroll points out it's easy to shoot this theory full of holes, because without further, intensive research, there's literally no way to know who wrote what and who read what and why? For example, how do we know who read Gothic fiction and why - can we honestly prove that people wrote and flocked to this new art form in a reaction to the faith in reason of The Enlightenment? No. However, he does indicate that simply the rise of horror - which presupposes the supernatural and something "unknown" - during the Age of Reason, which believed nothing needed to be unknown by man, interesting enough to promote further study.

2. A much easier connection can be made, Carroll says, in thinking how one conceptual birth - The Age of Reason and Enlightenment - helped bring about another, simply in one creating a structure the other could violate. In short, and very paraphrased form: The Enlightenment, with its promotion of naturalistic theories and desire to develop a scientific, natural view of the world, gave horror/Gothic fiction the perfect backdrop against which to develop its "monsters".

So, in other words, because:

"the Enlightenment made available the kind of conception of nature or the kind of cosmology needed to create a sense of horror." (pg. 57)

by:

"the sense of natural violation that attends art-horror" (pg. 57)

In other words, the Enlightenment developed a general idea of what the "natural" world was for the general reading public, which gave room for stories to create monsters and situations that violated that natural world, in essence, helping give horror natural rules to break with its monsters.

Again, Carroll readily admits that more research is needed to support or refute either claim. And, yeah, once again, we're probably splitting hairs here. But still, it provides plenty to think about....

Published on February 12, 2012 16:30

February 11, 2012

The Philosophy of Horror - Mini Review #1

As part of a semester project for my "Film & Philosophy" class, I'm reading

The Philosophy of Horror

, by film philosopher and critic, Noel Carroll. Not exactly sure what the thrust of my focus is going to be, I just know I've decided to focus my semester's study on the development of the horror movie and horror cinema in general.

I need to write a critical review of a book on film and philosophy, (I'm reviewing Philosophy of Horror for that), give a presentation on one of our assigned texts, and write a final paper. (pretty standard grad school fare) Since I chose to give my presentation on a critical analysis of David Lynch's Lost Highway (not necessarily horror, but definitely very dark and surreal), it makes sense to focus on the dark and the weird and the supernatural.

So, like my previous review of

The Woman In Black

, I'm going to thresh out my initial thoughts on The Philosophy of Horror, get my ideas in order, while sharing them with you all here on the blog. Here's my first bit of reflection.

So, like my previous review of

The Woman In Black

, I'm going to thresh out my initial thoughts on The Philosophy of Horror, get my ideas in order, while sharing them with you all here on the blog. Here's my first bit of reflection.

For much of the first forty pages, Carroll spends most his time articulating WHY attempting to generate a "philosophy of horror" is important, defining what horror is, and considering two important paradoxes when it comes to audiences - and readers - of horror:

1. how can anyone be frightened by what they know doesn't exist?

2. why would anyone be interested in horror, when being horrified is so unpleasant?

One key factor that Carroll emphasizes early on is his focus: analyzing the emotional effect horror is intended to have on its audience, by analyzing the emotional state and reactions the main characters of horror movies and books and plays display, and how audiences and readers associate and empathize with those reactions. To him, THAT is the key element to consider when developing a philosophy of horror.

He also differentiates between something that is designed to produce sensations of horror and things that are merely horrific. For example, stories of murder and death and mass genocide in the newspapers and on television and documentaries - or, even in things like war movies - are not horror. They are horrific.

Carroll also differentiates between things that "shock" or produce "jump-scares" and horror. The element of "shock" is used across genres, from crime movies to science fiction and fantasy, is a story-telling element, NOT a defining element of horror itself.

Because of the two above examples and for the purpose of this work, Carroll deigns to coin the term "art-horror" for all fictive works designed to produce sensations of horror in audiences and readers. This, in many ways, rules out a lot of things from the very beginning, something I hope he'll clarify throughout the rest the book.

1. how can anyone be frightened by what they know doesn't exist?

Carroll spends a lot of time here analyzing the core of the "art-horror" movie, novel and play - the monster. What makes the monster dangerous, threatening, and impure. He focuses especially on that last element, how monsters really need to be considered impure to generate feelings of "art-horror" in the audience: fear, disgust, madness, irrationality, agitation. He then defines this key element of the "monster" - not limited to the supernatural - as being impure, in that they are:

"unnatural relative to a culture's conceptual scheme of nature. They do not fit into the scheme, the violate it. They are threats to common knowledge. They are formless, and render those who encounter them insane, mad, deranged. They are challenges to the foundations of a culture's way of thinking" (pg. 34)

"native to places outside of and/or unknown to the human world. Or, the creatures come from marginal, hidden, abandoned sites: graveyards, abandoned towers and castles, sewers, or old houses...they belong to environs outside of and unknown to ordinary social intercourse" (pg. 35)

Of course, many of these "monsters" don't really exist, so Carroll comes back again to the characterization of the movie's "positive" main characters, and our reaction to their reactions, the strength of our emotional connection to them. He says in this that these monsters present a "cognitive threat" to our perceptions of the way the world should be.

Carroll emphasizes the need for all three elements to wholly create the monster: that it must be dangerous, threatening, and impure. He cites The Fly as an example. Though the positive characters and certainly audience are probably disgusted by the main protagonist's transformation throughout the movie into an impure abomination, for most the movie, they feel sympathy for this guy turning into a human fly. Even the guy's girlfriend feels sympathy and tries to deal with the situation. He (the human fly) doesn't truly become threatening and dangerous until the movie's very end.

Carroll emphasizes the need for all three elements to wholly create the monster: that it must be dangerous, threatening, and impure. He cites The Fly as an example. Though the positive characters and certainly audience are probably disgusted by the main protagonist's transformation throughout the movie into an impure abomination, for most the movie, they feel sympathy for this guy turning into a human fly. Even the guy's girlfriend feels sympathy and tries to deal with the situation. He (the human fly) doesn't truly become threatening and dangerous until the movie's very end.

So in this case, Carroll disclassifies The Fly as "art-horror" along these two lines:

1. he's not dangerous or threatening until the end

2. for most the movie, other "positive" characters feel either sympathy or pity for him, thereby possibly engendering sympathy and pity in the audience, which, according to Carroll's notion, is not the emotional reaction to the "monster" art-horror films are intending to produce.

2. why would anyone be interested in horror, when being horrified is so unpleasant?

This is something he hasn't delved into yet, spending most his time so far defining the term "art-horror" and what exactly monsters are, and why we find them threatening. At the end of the introduction, he states that this is his goal: to thresh out this paradox of audiences and readers seeking out "art-horror", as he hopes to try and articulate - even if only for himself - why the horror genre is so compelling.

One last bit that was especially thought provoking for ME as a reader and especially a writer is where he differentiates between art-horror and what he calls "tales of dread", or works of the "fantastic", such as the Twilight Zone, Outer Limits, etc. They are peripheral to the horror genre, but in Carroll's estimation....

"nevertheless, I do think that there is an important difference between this type of story - which I want to call tales of dread - and horror stories. Specifically, the emotional response they elicit seems to be quite different than that engendered by art-horror. The uncanny event which tops off such stories cause a sense of unease and awe, perhaps of momentary anxiety and foreboding. These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe. Where art-horror involves disgust as a central figure, what might be called art-dread does not" (pg. 42)

Now, genre definitions are hazy and fluid at best, which Carroll openly admits throughout the work, and goes on to state that because both "art-horror" and "art-dread" deal with supernatural or preternatural events, they are intimately related, just that he wanted to illustrate that both factions are discernible. This little bit right here, though, provided ME with much food for thought as a writer and creator, about what types of emotions I want to inspire in readers:

These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe.

This is the realm many of my stories return to, it's the framework from which I form all my story ideas, even (or especially) my Hiram Grange title. So does this mean I don't write horror?

Hmm. Who knows? And maybe the point's moot, splitting hairs. BUT, I sometimes think - maybe arrogantly - that a lot of the bad fiction written across ALL genres today has been produced without really thinking very deeply about where the ideas have come from, why they've been generated, and what we want to inspire in our readers. At the very best, I'm driving myself deeper into thinking what it is I want to write and why.

At the very least? Pretty cool way to spend a semester of grad school....

I need to write a critical review of a book on film and philosophy, (I'm reviewing Philosophy of Horror for that), give a presentation on one of our assigned texts, and write a final paper. (pretty standard grad school fare) Since I chose to give my presentation on a critical analysis of David Lynch's Lost Highway (not necessarily horror, but definitely very dark and surreal), it makes sense to focus on the dark and the weird and the supernatural.

So, like my previous review of

The Woman In Black

, I'm going to thresh out my initial thoughts on The Philosophy of Horror, get my ideas in order, while sharing them with you all here on the blog. Here's my first bit of reflection.

So, like my previous review of

The Woman In Black

, I'm going to thresh out my initial thoughts on The Philosophy of Horror, get my ideas in order, while sharing them with you all here on the blog. Here's my first bit of reflection.For much of the first forty pages, Carroll spends most his time articulating WHY attempting to generate a "philosophy of horror" is important, defining what horror is, and considering two important paradoxes when it comes to audiences - and readers - of horror:

1. how can anyone be frightened by what they know doesn't exist?

2. why would anyone be interested in horror, when being horrified is so unpleasant?

One key factor that Carroll emphasizes early on is his focus: analyzing the emotional effect horror is intended to have on its audience, by analyzing the emotional state and reactions the main characters of horror movies and books and plays display, and how audiences and readers associate and empathize with those reactions. To him, THAT is the key element to consider when developing a philosophy of horror.

He also differentiates between something that is designed to produce sensations of horror and things that are merely horrific. For example, stories of murder and death and mass genocide in the newspapers and on television and documentaries - or, even in things like war movies - are not horror. They are horrific.

Carroll also differentiates between things that "shock" or produce "jump-scares" and horror. The element of "shock" is used across genres, from crime movies to science fiction and fantasy, is a story-telling element, NOT a defining element of horror itself.

Because of the two above examples and for the purpose of this work, Carroll deigns to coin the term "art-horror" for all fictive works designed to produce sensations of horror in audiences and readers. This, in many ways, rules out a lot of things from the very beginning, something I hope he'll clarify throughout the rest the book.

1. how can anyone be frightened by what they know doesn't exist?

Carroll spends a lot of time here analyzing the core of the "art-horror" movie, novel and play - the monster. What makes the monster dangerous, threatening, and impure. He focuses especially on that last element, how monsters really need to be considered impure to generate feelings of "art-horror" in the audience: fear, disgust, madness, irrationality, agitation. He then defines this key element of the "monster" - not limited to the supernatural - as being impure, in that they are:

"unnatural relative to a culture's conceptual scheme of nature. They do not fit into the scheme, the violate it. They are threats to common knowledge. They are formless, and render those who encounter them insane, mad, deranged. They are challenges to the foundations of a culture's way of thinking" (pg. 34)

"native to places outside of and/or unknown to the human world. Or, the creatures come from marginal, hidden, abandoned sites: graveyards, abandoned towers and castles, sewers, or old houses...they belong to environs outside of and unknown to ordinary social intercourse" (pg. 35)

Of course, many of these "monsters" don't really exist, so Carroll comes back again to the characterization of the movie's "positive" main characters, and our reaction to their reactions, the strength of our emotional connection to them. He says in this that these monsters present a "cognitive threat" to our perceptions of the way the world should be.

Carroll emphasizes the need for all three elements to wholly create the monster: that it must be dangerous, threatening, and impure. He cites The Fly as an example. Though the positive characters and certainly audience are probably disgusted by the main protagonist's transformation throughout the movie into an impure abomination, for most the movie, they feel sympathy for this guy turning into a human fly. Even the guy's girlfriend feels sympathy and tries to deal with the situation. He (the human fly) doesn't truly become threatening and dangerous until the movie's very end.

Carroll emphasizes the need for all three elements to wholly create the monster: that it must be dangerous, threatening, and impure. He cites The Fly as an example. Though the positive characters and certainly audience are probably disgusted by the main protagonist's transformation throughout the movie into an impure abomination, for most the movie, they feel sympathy for this guy turning into a human fly. Even the guy's girlfriend feels sympathy and tries to deal with the situation. He (the human fly) doesn't truly become threatening and dangerous until the movie's very end.So in this case, Carroll disclassifies The Fly as "art-horror" along these two lines:

1. he's not dangerous or threatening until the end

2. for most the movie, other "positive" characters feel either sympathy or pity for him, thereby possibly engendering sympathy and pity in the audience, which, according to Carroll's notion, is not the emotional reaction to the "monster" art-horror films are intending to produce.

2. why would anyone be interested in horror, when being horrified is so unpleasant?

This is something he hasn't delved into yet, spending most his time so far defining the term "art-horror" and what exactly monsters are, and why we find them threatening. At the end of the introduction, he states that this is his goal: to thresh out this paradox of audiences and readers seeking out "art-horror", as he hopes to try and articulate - even if only for himself - why the horror genre is so compelling.

One last bit that was especially thought provoking for ME as a reader and especially a writer is where he differentiates between art-horror and what he calls "tales of dread", or works of the "fantastic", such as the Twilight Zone, Outer Limits, etc. They are peripheral to the horror genre, but in Carroll's estimation....

"nevertheless, I do think that there is an important difference between this type of story - which I want to call tales of dread - and horror stories. Specifically, the emotional response they elicit seems to be quite different than that engendered by art-horror. The uncanny event which tops off such stories cause a sense of unease and awe, perhaps of momentary anxiety and foreboding. These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe. Where art-horror involves disgust as a central figure, what might be called art-dread does not" (pg. 42)

Now, genre definitions are hazy and fluid at best, which Carroll openly admits throughout the work, and goes on to state that because both "art-horror" and "art-dread" deal with supernatural or preternatural events, they are intimately related, just that he wanted to illustrate that both factions are discernible. This little bit right here, though, provided ME with much food for thought as a writer and creator, about what types of emotions I want to inspire in readers:

These events are constructed to move the audience rhetorically to the point that one entertains the idea that unavowed, unknown, perhaps concealed and inexplicable forces rule the universe.

This is the realm many of my stories return to, it's the framework from which I form all my story ideas, even (or especially) my Hiram Grange title. So does this mean I don't write horror?

Hmm. Who knows? And maybe the point's moot, splitting hairs. BUT, I sometimes think - maybe arrogantly - that a lot of the bad fiction written across ALL genres today has been produced without really thinking very deeply about where the ideas have come from, why they've been generated, and what we want to inspire in our readers. At the very best, I'm driving myself deeper into thinking what it is I want to write and why.

At the very least? Pretty cool way to spend a semester of grad school....

Published on February 11, 2012 04:24

February 5, 2012

The Woman in Black - A Review

Going to be doing a lot of these, next few months. One of my graduate classes this semester is "Film & Philosophy", so because I'll be watching lots of movies and reading lots about movies, movie-making, philosophy and the philosophies behind movie-making, I'm going to be in that mode. Might as review the movies I see here on the blog, help sort things out in my head for my presentations and papers this semester.

Anyway, movie reviews are a bit different than book reviews, so if this is rougher than my usual reviews, please forgive me. In any case...

So, here's the official synopsis of "The Woman in Black", starring he of Harry Potter fame, Daniel Radcliffe:

So, here's the official synopsis of "The Woman in Black", starring he of Harry Potter fame, Daniel Radcliffe:

A young lawyer travels to a remote village to organize a recently deceased client's papers, where he discovers the ghost of a scorned woman set on vengeance.

Here's a link to the previews, if you haven't seen it, yet.

Now, here's the rub for me: I'm not a fan of many horror movies. Part of the problem is how far they stretch believability in the main protagonist's reactions to strange, odd things. I mean, how many times can a main character see or hear or experience something strange or frightening, yet still decide to "stick around" where these things are happening?

*SPOILER ALERT*

And, here's where "The Woman in Black" succeeds - in a way that a novel never could, even. Now, give me some lee-way, here. I'm very much a novice when it comes to analyzing film. But generally, unless a movie makes a point of telling something DIRECTLY from a character's strict limited point of view, with narration and voice over to boot - "Memento" comes to mind - even though we see things through different character's perspectives, the camera is in charge, and we experience a movie from a ghostly, third-person omniscient perspective sitting right next to the character, not in the character's head.

And this is where "The Woman in Black" - IMHO - succeeds in spades. For the first forty-five minutes or so, Daniel Radcliffe's character sees very little. Just an odd looking woman in black standing outside this old house, lurking in the woods, and that's all. All the other great stuff happens off the side, in the shadows, just as he's turned his head, closed a door, walked down a hallway. Successfully amping up the dramatic tension for us, the viewers, but not stretching the reality or believability....

...because Kipps (Radcliffe) didn't see it! And therefore, we don't have a lot of those moments early on when he sees tons of weird stuff but dismisses it as the "wind" or notches it up to his "fatigue" or "shadows on the wall." Meanwhile, in an extremely immersive experience, WE are pulled right into the movie, scanning corners and doorways - seemingly innocuous, innocent parts of the setting that are now ALL looming and threatening.

Now, Kipps (Radcliffe) shows up in this weird little village, and we have the classic, requisite sketchy villagers who all mumble in raspy voices, "Dontcha go up thar to Marsh House, sar!"

And of course, Kipps persists anyway....but we're set up nicely with this early on, because he's lectured rather harshly by his boss back at his London law firm that this was his last chance to prove himself and keep his job. He's a widower with a son, mounds of debt is alluded to nicely with a glancing camera shot at a stack of unpaid bills, so he MUST do this job. He's desperate to, in fact, to provide for his son. Good enough motive to pay sketchy, backwards villagers no mind.

And he's a haunted man himself. His wife dead in childbirth, he's primed for a supernatural encounter with haunting visions throughout the movie of his wife ghosting around. So he's mourning, questioning his beliefs about this world and the one beyond, under duress, desperate to do his job. All great ingredients.

One thing occurred to me while viewing this film: a true Gothic tale would be very hard to tell in modern times, because a key element is a sense of isolation. Being cut off from the outside world, unable to communicate and go for help.

Obviously, the setting here is perfect: turn of the century when small villages have no telephone services, the telegraph only runs sporadically, only one person in the whole village owns a car, and the house itself - on a mountainside in the marshes, when high tide washes away the road and effectively cuts our protagonists off from the mainland. Setting this in modern times would require lots more manipulation of the plot to achieve these things, which opens the movie up for more artificiality.

And, the ending. Won't spoil it here, but the resolution is nice. There's no pat answer for stopping "The Woman in Black", but the movie still manages to end in way that gives comfort and release of tension. An excellent film, well-worth the viewing. May even have to go see it again, when it hits the bargain theaters....

Anyway, movie reviews are a bit different than book reviews, so if this is rougher than my usual reviews, please forgive me. In any case...

So, here's the official synopsis of "The Woman in Black", starring he of Harry Potter fame, Daniel Radcliffe:

So, here's the official synopsis of "The Woman in Black", starring he of Harry Potter fame, Daniel Radcliffe: A young lawyer travels to a remote village to organize a recently deceased client's papers, where he discovers the ghost of a scorned woman set on vengeance.

Here's a link to the previews, if you haven't seen it, yet.

Now, here's the rub for me: I'm not a fan of many horror movies. Part of the problem is how far they stretch believability in the main protagonist's reactions to strange, odd things. I mean, how many times can a main character see or hear or experience something strange or frightening, yet still decide to "stick around" where these things are happening?

*SPOILER ALERT*

And, here's where "The Woman in Black" succeeds - in a way that a novel never could, even. Now, give me some lee-way, here. I'm very much a novice when it comes to analyzing film. But generally, unless a movie makes a point of telling something DIRECTLY from a character's strict limited point of view, with narration and voice over to boot - "Memento" comes to mind - even though we see things through different character's perspectives, the camera is in charge, and we experience a movie from a ghostly, third-person omniscient perspective sitting right next to the character, not in the character's head.

And this is where "The Woman in Black" - IMHO - succeeds in spades. For the first forty-five minutes or so, Daniel Radcliffe's character sees very little. Just an odd looking woman in black standing outside this old house, lurking in the woods, and that's all. All the other great stuff happens off the side, in the shadows, just as he's turned his head, closed a door, walked down a hallway. Successfully amping up the dramatic tension for us, the viewers, but not stretching the reality or believability....

...because Kipps (Radcliffe) didn't see it! And therefore, we don't have a lot of those moments early on when he sees tons of weird stuff but dismisses it as the "wind" or notches it up to his "fatigue" or "shadows on the wall." Meanwhile, in an extremely immersive experience, WE are pulled right into the movie, scanning corners and doorways - seemingly innocuous, innocent parts of the setting that are now ALL looming and threatening.

Now, Kipps (Radcliffe) shows up in this weird little village, and we have the classic, requisite sketchy villagers who all mumble in raspy voices, "Dontcha go up thar to Marsh House, sar!"

And of course, Kipps persists anyway....but we're set up nicely with this early on, because he's lectured rather harshly by his boss back at his London law firm that this was his last chance to prove himself and keep his job. He's a widower with a son, mounds of debt is alluded to nicely with a glancing camera shot at a stack of unpaid bills, so he MUST do this job. He's desperate to, in fact, to provide for his son. Good enough motive to pay sketchy, backwards villagers no mind.

And he's a haunted man himself. His wife dead in childbirth, he's primed for a supernatural encounter with haunting visions throughout the movie of his wife ghosting around. So he's mourning, questioning his beliefs about this world and the one beyond, under duress, desperate to do his job. All great ingredients.

One thing occurred to me while viewing this film: a true Gothic tale would be very hard to tell in modern times, because a key element is a sense of isolation. Being cut off from the outside world, unable to communicate and go for help.

Obviously, the setting here is perfect: turn of the century when small villages have no telephone services, the telegraph only runs sporadically, only one person in the whole village owns a car, and the house itself - on a mountainside in the marshes, when high tide washes away the road and effectively cuts our protagonists off from the mainland. Setting this in modern times would require lots more manipulation of the plot to achieve these things, which opens the movie up for more artificiality.

And, the ending. Won't spoil it here, but the resolution is nice. There's no pat answer for stopping "The Woman in Black", but the movie still manages to end in way that gives comfort and release of tension. An excellent film, well-worth the viewing. May even have to go see it again, when it hits the bargain theaters....

Published on February 05, 2012 04:01

February 2, 2012

Story In Morpheus Tales: The Best Weird Fiction, Volume 1

Recently I blogged about starting on a blank slate, leaving behind a lot of the misconceptions I'd developed about writing and publishing. Basically "unlearning" all those "do's and don't's" I'd heard for about two years, and had ingrained in myself as hard-line, carved-in-stone rules of getting published. Not to disrespect those who preached those rules to me, because they were giving sound advice with the best of intentions, but I've come to realize I need to follow my own path in publishing, which includes listening to others, but also realizing this is MY writing journey, not theirs.

Faith plays a big part in this journey. Realizing that no matter what I do, no matter how hard I work or write or do the "right things", ultimately, this whole thing is out of my hands, in the hands of Someone Much Bigger Than Me (But that's another blog post for another time).

Case in point: the mantra that horror writers must only sell their short stories for the highest pay, or that submitting to a non-paying market is a waste of time, waste of effort, waste of that story, and even WORSE: a black mark on your record. Because doing so will doom you forever to writing in the ghettos. AND, if you ever do have a story accepted into one of these publications early on, you must forever shun them like skeletons in the closet, or forever face the ridicule of your peers.

THIS IS ONE OF THOSE FALSE ASSUMPTIONS.

I realized this in my talks with the senior acquisitions editor from HarperTeen. She didn't care one WHIT where my short stories had been published, by whom, or for how much. All she cared about was the immediate work, how good IT was, and if it was right for her publishing house.

Interesting.

Now, don't misunderstand. I think all writers should be careful and meticulous and make sure that NOTHING but the best work leaves their hands. This involves OBSESSIVE re-reading and re-writing, having good beta readers who aren't afraid to call "crap" what it is, and a dedication to always improving one's prose.

And, on a personal note, all writers should have goals higher than were they are to strive towards. I've yet to make a professional sale. Someday, I want to crack Apex, Cemetery Dance, and Black Static. When I'm done with this current project, I'm going on a slew of short stories, to practice the craft.

But I'm kinda done with this whole: "If you didn't sell it, it must crap; if the magazine didn't pay for it, it must crap, and the magazine must be crap." Because it DOESN'T pan out. Everything is case-by-case these days. Yeah, there are some short stories I'm a little embarrassed of, that were published in rags (literally) that I don't want to see the light of day.

But "The Sliding" and Morpheus Tales aren't in that category. "The Sliding" is a neat, creepy little story - that's also pretty personal - and Morpheus Tales is a pretty cool little UK magazine that's featured the work of Michael Laimo, Joe D'Lacey, Aaron Poulson and others, which is pretty cool company. So I'm happy to announce the inclusion of my humble little story, "The Sliding" in Morpheus Tales' first Best of Collection, Morpheus Tales: The Best Weird Fiction, Volume 1. To buy, follow the link.

For the first time collected together in one volume, the best weird fiction from Morpheus Tales, the UK's most controversial weird fiction magazine! Only the very best weird fiction has been hand-picked from the Morpheus Tales archives to create this first collected volume of the magazine Christopher Fowler calls "edgy and dark". Featuring fiction by Lyn Cannaday, Robert T. Canipe, Steven Lee Climer, Nickolas Cook, Garon Cockrell, Nick Day, Vic Fortezza, Ken Goldman, Gary Hewitt, Todd Austin Hunt, Michael Laimo, Kevin Lucia, Adrian Ludens, Christian McPhate, Mari Mitchell, Theresa C. Newbill, Aaron A. Polson, Jonathan J. Schlosser, Tommy B. Smith, Alan Spencer, Wayne Summers, Randy Young, Mark Zirbel, Lee Clark Zumpe. Established horror best-sellers rub shoulders with rising stars and newcomers in this diverse collection of short weird fiction.

For the first time collected together in one volume, the best weird fiction from Morpheus Tales, the UK's most controversial weird fiction magazine! Only the very best weird fiction has been hand-picked from the Morpheus Tales archives to create this first collected volume of the magazine Christopher Fowler calls "edgy and dark". Featuring fiction by Lyn Cannaday, Robert T. Canipe, Steven Lee Climer, Nickolas Cook, Garon Cockrell, Nick Day, Vic Fortezza, Ken Goldman, Gary Hewitt, Todd Austin Hunt, Michael Laimo, Kevin Lucia, Adrian Ludens, Christian McPhate, Mari Mitchell, Theresa C. Newbill, Aaron A. Polson, Jonathan J. Schlosser, Tommy B. Smith, Alan Spencer, Wayne Summers, Randy Young, Mark Zirbel, Lee Clark Zumpe. Established horror best-sellers rub shoulders with rising stars and newcomers in this diverse collection of short weird fiction.

Faith plays a big part in this journey. Realizing that no matter what I do, no matter how hard I work or write or do the "right things", ultimately, this whole thing is out of my hands, in the hands of Someone Much Bigger Than Me (But that's another blog post for another time).

Case in point: the mantra that horror writers must only sell their short stories for the highest pay, or that submitting to a non-paying market is a waste of time, waste of effort, waste of that story, and even WORSE: a black mark on your record. Because doing so will doom you forever to writing in the ghettos. AND, if you ever do have a story accepted into one of these publications early on, you must forever shun them like skeletons in the closet, or forever face the ridicule of your peers.

THIS IS ONE OF THOSE FALSE ASSUMPTIONS.

I realized this in my talks with the senior acquisitions editor from HarperTeen. She didn't care one WHIT where my short stories had been published, by whom, or for how much. All she cared about was the immediate work, how good IT was, and if it was right for her publishing house.

Interesting.

Now, don't misunderstand. I think all writers should be careful and meticulous and make sure that NOTHING but the best work leaves their hands. This involves OBSESSIVE re-reading and re-writing, having good beta readers who aren't afraid to call "crap" what it is, and a dedication to always improving one's prose.

And, on a personal note, all writers should have goals higher than were they are to strive towards. I've yet to make a professional sale. Someday, I want to crack Apex, Cemetery Dance, and Black Static. When I'm done with this current project, I'm going on a slew of short stories, to practice the craft.

But I'm kinda done with this whole: "If you didn't sell it, it must crap; if the magazine didn't pay for it, it must crap, and the magazine must be crap." Because it DOESN'T pan out. Everything is case-by-case these days. Yeah, there are some short stories I'm a little embarrassed of, that were published in rags (literally) that I don't want to see the light of day.

But "The Sliding" and Morpheus Tales aren't in that category. "The Sliding" is a neat, creepy little story - that's also pretty personal - and Morpheus Tales is a pretty cool little UK magazine that's featured the work of Michael Laimo, Joe D'Lacey, Aaron Poulson and others, which is pretty cool company. So I'm happy to announce the inclusion of my humble little story, "The Sliding" in Morpheus Tales' first Best of Collection, Morpheus Tales: The Best Weird Fiction, Volume 1. To buy, follow the link.