Kevin Lucia's Blog, page 48

March 18, 2012

Horror and Post-Modernism

So these last two posts (today and possibly tomorrow) are going to be my final thoughts on Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, because this is dragging out a little longer than I'd initially thought it would. So, here we go:

Horror and Post-Modernism

postmodernism - a way of approaching traditional ideas and practices in non-traditional ways that deviate from pre-established superstructural modes. (Wikipedia)

So, because I've got this idea I want to write for my paper about horror today and what that says about our current culture, when I saw this snippet at the very end of Carroll's work, I perked up:

"...I would like to suggest is that the contemporary horror genre is the exoteric expression of the same feelings that are expressed in the esoteric discussions of the intelligentsia with respect to postmodernism."

Some definitions:

exoteric: refers to knowledge that is outside of and independent from anyone's experience and can be ascertained by anyone; cf. common sense.

esoteric: ideas preserved or understood by a small group or those specially initiated, or of rare or unusual interest

intelligentsia: a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them.

In basic terms, according to Carroll, postmodernism states that our beliefs of the world, and our way of looking at and understanding the world are arbitrary. They can be deconstructed, pulled apart, and don't actually refer to the real world. Carroll makes the point that he himself is not convinced of post-modernism's claims, but also says its effect on our culture - and horror - can't be denied.

Here's where he struck me. Because I don't consider myself a postmodernist. And I don't know enough about postmodern art to know if Carroll's next point is valid, but this Wiki definition of it seems to correspond:

post-modern art: the recycling of past styles and themes in a modern-day context

as Carroll says this:

"...whether for purposes of political criticism or for nostalgia, postmodern art lives off its inheritance....it proceeds by recombining acknowledged elements of the past in a way that suggests that the root of creativity is to be found in looking backward (emphasis mine)" pg. 211

And then, the coup de grace, connecting this to horror:

"...the contemporary horror genre....differs from previous cycles (of horror) in certain respects that also bear comparison with the themes of postmodernism. First, works of contemporary horror often refer to the history of the genre quite explicitly. King's IT reanimates a gallery of classic monsters; the movie Creepshow by King and Romero is a homage to EC horror comics of the fifties; horror movies nowadays frequently make allusions to other horror films while Fright Night (the original, thanks) includes a fictional horror show host as a character; horror writers freely refer to other writers and to other examples of the genre; they especially make reference to classic horror movies and characters." (pg. 211)

and this...

"...the creators and the consumers of horror fictions are aware they are operating within a shared tradition, and this is acknowledged openly, with great frequency and gusto (emphasis mine) pg. 211

Okay.

Now, I'm going to admit, this totally throws me. Not the bit on horror writers referencing its history, knowing we're part of a shared tradition. I blogged last year about the THUNDERING revelation of how WEAK my knowledge of genre history was, when I blogged about the evening I spent with Tom Monteleone, F. Paul Wilson, and Stuart David Schiff. That started me on a mission to educate myself, and I've spent most the last year reading horror from the 70's, 80's and 90's.

Also, there's Brian Keene's Keynote Address from AnthoCon 2011, "Roots", about how important it is for young readers and writers of horror to be well-versed in the history of the genre. That alone reaffirmed my mission to educate myself in the history of the genre.

But....post-modernist?

I'm a post-modern....artist?

It's a strange label to assume. Now, granted....it seems one can labor in their chosen art from a post-modern perspective, without viewing the world as a post-modernist. I suppose. I hope, because that seems to be where I'm at. Because of my faith and the way I've been raised, I don't really view the world as a post-modernist - I've got pretty traditional views about things (but they're for me and my family), and I think they're important enough not to deviate from, to pass on.

But as a horror-writer...I guess I'd say I am post-modern, because the definition for post-modern art is a little different than the definition of a post-modern world perspective. As I've just become aware in the last year or so, as a horror writer, I'm part of a shared tradition; a tradition I need to be intimately knowledgeable of if I ever hope to take old and time-honored stories and tropes and twist them, mold them and shape them into my own creations for new readers who - also intimately aware of the horror tradition - will find resonance in them because of those classic threads, but who will also want to read them (and, of course, publish them) because I've made those stories and tropes mine, and therefore new and fresh.

Huh.

I guess that just adds another layer of complexity upon the walking contradiction that I already am. As a father, husband, teacher - I'm not post-modernist at all. Pretty traditional, if conservative in how I talk about and share my beliefs (ergo, I don't shove them on anyone else). However, as a horror writer, not only do I NEED to be post-modern in hopes of gathering an audience and getting published, I sorta....STRIVE to be...because I don't want to re-write the same old thing. I want to use those same, classic themes and tropes...but make them mine.

Wow. Guess we never stop learning about ourselves, as we continue to perfect our craft....

Horror and Post-Modernism

postmodernism - a way of approaching traditional ideas and practices in non-traditional ways that deviate from pre-established superstructural modes. (Wikipedia)

So, because I've got this idea I want to write for my paper about horror today and what that says about our current culture, when I saw this snippet at the very end of Carroll's work, I perked up:

"...I would like to suggest is that the contemporary horror genre is the exoteric expression of the same feelings that are expressed in the esoteric discussions of the intelligentsia with respect to postmodernism."

Some definitions:

exoteric: refers to knowledge that is outside of and independent from anyone's experience and can be ascertained by anyone; cf. common sense.

esoteric: ideas preserved or understood by a small group or those specially initiated, or of rare or unusual interest

intelligentsia: a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them.

In basic terms, according to Carroll, postmodernism states that our beliefs of the world, and our way of looking at and understanding the world are arbitrary. They can be deconstructed, pulled apart, and don't actually refer to the real world. Carroll makes the point that he himself is not convinced of post-modernism's claims, but also says its effect on our culture - and horror - can't be denied.

Here's where he struck me. Because I don't consider myself a postmodernist. And I don't know enough about postmodern art to know if Carroll's next point is valid, but this Wiki definition of it seems to correspond:

post-modern art: the recycling of past styles and themes in a modern-day context

as Carroll says this:

"...whether for purposes of political criticism or for nostalgia, postmodern art lives off its inheritance....it proceeds by recombining acknowledged elements of the past in a way that suggests that the root of creativity is to be found in looking backward (emphasis mine)" pg. 211

And then, the coup de grace, connecting this to horror:

"...the contemporary horror genre....differs from previous cycles (of horror) in certain respects that also bear comparison with the themes of postmodernism. First, works of contemporary horror often refer to the history of the genre quite explicitly. King's IT reanimates a gallery of classic monsters; the movie Creepshow by King and Romero is a homage to EC horror comics of the fifties; horror movies nowadays frequently make allusions to other horror films while Fright Night (the original, thanks) includes a fictional horror show host as a character; horror writers freely refer to other writers and to other examples of the genre; they especially make reference to classic horror movies and characters." (pg. 211)

and this...

"...the creators and the consumers of horror fictions are aware they are operating within a shared tradition, and this is acknowledged openly, with great frequency and gusto (emphasis mine) pg. 211

Okay.

Now, I'm going to admit, this totally throws me. Not the bit on horror writers referencing its history, knowing we're part of a shared tradition. I blogged last year about the THUNDERING revelation of how WEAK my knowledge of genre history was, when I blogged about the evening I spent with Tom Monteleone, F. Paul Wilson, and Stuart David Schiff. That started me on a mission to educate myself, and I've spent most the last year reading horror from the 70's, 80's and 90's.

Also, there's Brian Keene's Keynote Address from AnthoCon 2011, "Roots", about how important it is for young readers and writers of horror to be well-versed in the history of the genre. That alone reaffirmed my mission to educate myself in the history of the genre.

But....post-modernist?

I'm a post-modern....artist?

It's a strange label to assume. Now, granted....it seems one can labor in their chosen art from a post-modern perspective, without viewing the world as a post-modernist. I suppose. I hope, because that seems to be where I'm at. Because of my faith and the way I've been raised, I don't really view the world as a post-modernist - I've got pretty traditional views about things (but they're for me and my family), and I think they're important enough not to deviate from, to pass on.

But as a horror-writer...I guess I'd say I am post-modern, because the definition for post-modern art is a little different than the definition of a post-modern world perspective. As I've just become aware in the last year or so, as a horror writer, I'm part of a shared tradition; a tradition I need to be intimately knowledgeable of if I ever hope to take old and time-honored stories and tropes and twist them, mold them and shape them into my own creations for new readers who - also intimately aware of the horror tradition - will find resonance in them because of those classic threads, but who will also want to read them (and, of course, publish them) because I've made those stories and tropes mine, and therefore new and fresh.

Huh.

I guess that just adds another layer of complexity upon the walking contradiction that I already am. As a father, husband, teacher - I'm not post-modernist at all. Pretty traditional, if conservative in how I talk about and share my beliefs (ergo, I don't shove them on anyone else). However, as a horror writer, not only do I NEED to be post-modern in hopes of gathering an audience and getting published, I sorta....STRIVE to be...because I don't want to re-write the same old thing. I want to use those same, classic themes and tropes...but make them mine.

Wow. Guess we never stop learning about ourselves, as we continue to perfect our craft....

Published on March 18, 2012 05:18

March 17, 2012

It's the Little Things; Or, On the Kindness of Strangers

So, I collect redeemable cans. And bottles. And scrap metal (steel, tin, brass, copper, wire, aluminum, iron/cast iron). I try not to mention it too much; not because I'm ashamed, but I don't want folks thinking I'm playing up our financial situation:

"Oh, woe's me, we're so poor, I have to pick cans to get by...."

So, I collect redeemable cans. And bottles. And scrap metal (steel, tin, brass, copper, wire, aluminum, iron/cast iron). I try not to mention it too much; not because I'm ashamed, but I don't want folks thinking I'm playing up our financial situation:

"Oh, woe's me, we're so poor, I have to pick cans to get by...."

Truth is, I've been collecting cans and bottles for deposit and scrapping since I was a kid. On the can and bottle front - we lived next to a motorcross track. They had huge races every Saturday. I once asked Dad for an allowance, and his answer was:

"Every Sunday morning there's probably $20 worth of cans and bottles lying around that track. There's your allowance. It's all yours."

In the late 80's, early 90's, Dad got caught in a crunch caused by shifting paradigms in the workplace: suddenly, his almost fifteen years experience as a mechanical engineer and night school degree were no longer good enough to keep him employed. So he went through several patches of unemployment, one lasting almost my entire senior year of high school. At one point, the bank threatened to foreclose.

During that period, I saw him collect scrap with a dogged determination, as well as take any kind of odd job he could - carpentry, house painting, electricians' work - and that made a huge impact on me. Probably one of the first enduring lessons I learned about what it meant to be a MAN: you do whatever it takes to survive. Pride is an internal thing. Pride is self-generated.

Pride comes from survival. Not from the means of achieving said survival, but from the survival itself.

So we do the whole can-collecting, scrap collecting thing. Got a nice system, actually. We wash and bag and collect all the cans and bottles we consume ourselves and store them in my "garage" out back. We save them, because it's like putting money in the bank.

Then, beginning in March/April, two-three times a week I walk along the highway and back roads, looking for cans and bottles. Sometimes I do it on the way home from work. I have specific routes and interstates that are well-traveled, and always produce lots of cans and bottles.

A side-bonus: the walking is great exercise, too.

But we also collect scrap metal. You'd be surprised how much I find on my walks, hub caps, BIG pieces of the good stuff, too - aluminum and copper - and I collect all that, too. At home, we clean out all our tin cans and collect them, as well as empty hair spray bottles (some of those are aluminum), non-stick spray, deodorant, anything. Because in the end, it's all about weight, and the scrap metal processing center pays by the weight.

At the end of the summer, (or middle, depending on Abby's vacation), I take the cans and bottles to the redemption center, (they often run specials like 6.5 cents a can), and the scrap to our local scrap processing center. I usually walk away with something near $300 - $4oo all told, which provides for a stress-free, out-of-pocket vacation to the Adirondacks, and then a trip to Horrorfind (this year, we're aiming at the vacation, then AnthoCon).

So tonight, I was out walking, had done decently already, when a couple in their fifties pulled up behind me on - yep - their golf cart. Asked me what I was up to. I told them; about how I teach at a Catholic School, don't get paid over the summer, so I collect cans and scrap to help with vacation. These kind folks waved me back to their house, took my bags inside....and filled them, to the brim, overflowing, with cans and bottles.

Now, they probably only added 2-3 bucks to my haul. But the emotional impact is so much greater. It's small little, simple things like this that always gets me. They didn't presume anything about me, why this young guy is out alongside the road picking cans. They just gave me a ton of theirs, made nice conversation, then wished me a good evening.

And here's the kicker - this isn't the first time this has happened to me. It's at least the third.

Again. I'll repeat myself: it's the little things. That remind us we're not alone, here. That there's Someone Up There, always tossing little reminders our way that we're not alone, or - if you're not of the "Someone Up There" persuasion, it reminds us that people - real people - still care for their fellow man.

And that's something worth more than all the scrap metal and redeemable cans in the world.

Published on March 17, 2012 17:10

March 12, 2012

The Self-Publishing Go-Go 'Round....

So, I've been saving this post for a later date, but Mike Duran's post and the comments on it have got the brain juices flowing, so I think I'll share my final (sorta) thoughts on the rise self-publishing. Now first, a few qualifiers:

1. everyone has their own goals and publishing path

2. self-publishing doesn't automatically mean bad writing, anymore

3. the market is rapidly changing, many of the old "rules of publishing" are rapidly evolving, and the future of writing and publishing is very uncertain

4. this is MY opinion, why self-publishing is a BAD IDEA for ME, right now....but I think there are lots of young writers out there in the same position as me getting sold a line by folks who have platforms that WE DON'T, resources WE DON'T, and people need to be very careful what they do, because now, more than ever in the world of publishing: THERE ARE NO GUARANTEES. Whether or not you pursue self or traditional publishing. That having been said...

So, the crux of Mike Duran's post today is about a critique partner of his who waited nearly ten years in the pursuit of traditional publishing, before her trilogy was finally picked up by Tyndale, a traditional Christian publisher. Mike uses this scenario to discuss the matter of writers who have shown patience in seeking publication, wondering if perhaps that today, with the advent of digital self-publishing and the rise of Amazon, writers are far less patient than they used to be, to their detriment.

I'm not going to take issue with or analyze the responses to Mike's blog. A lot of the comments agree with him. Some merely express that traditional publishing is only one of many routes available, it all depends on a writers' personal journey, what they want to get out of writing (which is very true). Others disagree.

The problem, of course, is multifold:

1. the market is in turmoil. No one can predict what will happen in publishing over the next few years, so it's hard to come up with definitive answers to prove or disprove

2. a lot has come to light lately about publishers treating authors badly (the Leisure Fiction/Dorchester Publishing fiasco being only one example), so a "tear down the gates" mentality is definitely simmering, for good reasons

3. self-publishing HAS become much, much easier, quicker, and cheaper. And we here in America generally like things easier, quicker, and cheaper (and notice, I didn't say GOOD self-publishing. Just self-publishing)

And here's the one that gets under my skin the most:

4. several authors with built in audiences - which, I'm assuming, they built through traditional publishing - turning around and telling all us new writers that if we don't self-publish RIGHT NOW, we're all short-sighted, missing out, foolish for not earning all the instant cash they're earning.

Anyway, I can't tell you what I think is RIGHT or WRONG in self-publishing. I can only share my take, and what I plan to do, assume there are lots of writers out there in my position, who may or may not take something away from me sharing my ideas.

Now, first: I've taken some time to peruse some self-published works, most notably by Robert Swartwood and Dan Keohane. Both works that I read - Man of Wax and Margret's Ark - were top-notch. So much so, I have two more self-published works by both these authors sitting in my TBR pile, and will continue to buy more from them. Haven't read them yet, but I think Glen Krisch and Richard Wright's will probably be top-notch also.

Now, with these new-fangled self-publishing times, technically, there's nothing stopping me from publishing my novel soon as I'm finished with it, and joining these guys in the ranks.... except I'm NOT in their ranks, yet. And here's why:

1. I haven't done my time yet: these guys have been around for awhile. And yes, maybe if self-publishing had been cheaper ten years ago, they might not have waited so long to publish. But these guys have been knocking on their respective doors in publishing for a LONG TIME. I've just begun to knock. How can I possibly know if traditional publishing is really for me if I don't TRY it first?

Almost a year ago, Norman Partridge posted a blog along these lines - though he was also talking about micro-small presses - and he asked a very simple question that set me back on my heels: Have you really tried (traditional publishing)? And these guys HAVE. I haven't.

2. They've amassed a body of work that I HAVEN'T: And during all this time, these guys - I'm assuming - have been writing and re-writing several drafts of different novels, not only doing their best to get them out there - through agents and such - but also rewriting those novels, polishing them, in pursuit of excellence.

So, they've actually gotten several novels under their belt. I'm still writing my first, while a half-finished second languishes in a box. What do I have to self-publish that's been drafted and redrafted, cut, edited, vetted, and critiqued? What do I have that's made all the rounds? Nothing.

3. Jumping off number 2, these guys have street cred: they've done enough in the field, and have written quality enough work to get blurbed by some of the best in the business. I'm nowhere near there, yet. And maybe that's not necessary to self-publish. But I can tell you, most self-published books I'd never buy. But I risked it on Dan's work because I'm familiar with his short work, and he's got good "street cred" because of that. And, because I'd read his first, traditionally published novel. And, Robert's novel was blurbed by F. Paul Wilson.

I have very little "street cred". What's going to make my work stand out? NOTHING.

4. Finally...I CAN'T AFFORD IT. Traditional publishing is actually a much better choice for me - and, I'm assuming, a lot of other writers like me - because to self-publishing the RIGHT way, not only does it take the same time and patience and re-writing that any fiction takes, it takes MONEY and investment.

I can't speak from experience, but from this: as a self-published book, Man of Wax was put together nicely. Very nice cover and graphic design, it had clearly been edited, the layout and font and all that wasn't inferior to a traditionally published novel in any way. Same thing for Margret's Ark.

And that takes MONEY. For Adobe Invision, to commission cover art, to pay for layout and design, to pay an editor, then pay the fees to publish it on Amazon, buy the ISBN....and yes, it's an investment, true....one that a person like me has NO GUARANTEE of ever seeing a return on. Maybe I'll be one of these "overnight" sales successes that gush all over Facebook about themselves.

Most likely, I'll earn NEXT TO NOTHING. And, I'll have to pay all that over again for the next book, with the same risks.

And you know what? I'm willing to bet there's plenty of writers out there in the same position as I am. Which makes traditional publishing - and all the headaches involved - far more worth the effort in the end. Either way, if I'm not guaranteed a success, I'll pick the option that won't cost me money. Right now, being published by Shroud, Cemetery Dance, Apex, Samhain, Angry Robot, Abbaddon Books, Medallion Press FAR outweighs self-publishing, for that fact (and many, many others), alone.

**ATTENTION! SNARK ALERT! EASILY OFFENDED FOLKS, TURN BACK NOW!**

Also, too, I'm kinda getting sick of this refrain: "Oh, the BIG SIX will never let you in, and they're heading for a downfall, baby...."

Blah, blah. The Big Six aren't the only options for traditional publishing. There are tons of midlist houses out there, and yeah, many of them are owned by the Bix Six, and there's big and mean old Ingram Distribution as well....but this constant refrain always strikes me as lots of complaining. It's like the guys back when I played basketball who either wanted to start and be the leading scorer, or nothing at all. Instead of sitting the bench or being the sixth man or a role player, they'd take their ball, go home, and play pick-up on the court behind Wal-mart.

Because they didn't want to do their time. Wait their turn. And yeah, this is a little snarky, hence the above warning. But I just can't shake a feeling of annoyance at those arguments. Someone like Robert Swartwood? He did his time. Made the rounds with all the publishers, worked his ass off, and AFTER that decided self-publishing was his route. AFTER doing his time.

And I guess all these complaints about these evil New York houses and their abusive editors don't wash with me (and yeah, I have next to no experience in that area, so I really wouldn't know). Maybe I got lucky, but my interactions with an editor at HarperCollins were friendly, professional, and very helpful.

Even though her boss turned down my pitch because the "sales team didn't get it", no hard feelings. In fact, the story wouldn't be where it is today without her pushing and prodding me in different directions. But, as soon as it looked like we didn't have any further to go together, did I cry "foul", grab my ball, go home and self-publish? NO.

And again, maybe I've got to get screwed over a few more times. Who knows. But I'm one of those old fashioned folks who believe that getting told "No" is sometimes very, very important...and always for a reason.

Anyway, rant done. That's why for me - and, I'm willing to bet, for lots of other writers like me, out there - self-publishing just isn't the great deal lots of people are making it out to be...

1. everyone has their own goals and publishing path

2. self-publishing doesn't automatically mean bad writing, anymore

3. the market is rapidly changing, many of the old "rules of publishing" are rapidly evolving, and the future of writing and publishing is very uncertain

4. this is MY opinion, why self-publishing is a BAD IDEA for ME, right now....but I think there are lots of young writers out there in the same position as me getting sold a line by folks who have platforms that WE DON'T, resources WE DON'T, and people need to be very careful what they do, because now, more than ever in the world of publishing: THERE ARE NO GUARANTEES. Whether or not you pursue self or traditional publishing. That having been said...

So, the crux of Mike Duran's post today is about a critique partner of his who waited nearly ten years in the pursuit of traditional publishing, before her trilogy was finally picked up by Tyndale, a traditional Christian publisher. Mike uses this scenario to discuss the matter of writers who have shown patience in seeking publication, wondering if perhaps that today, with the advent of digital self-publishing and the rise of Amazon, writers are far less patient than they used to be, to their detriment.

I'm not going to take issue with or analyze the responses to Mike's blog. A lot of the comments agree with him. Some merely express that traditional publishing is only one of many routes available, it all depends on a writers' personal journey, what they want to get out of writing (which is very true). Others disagree.

The problem, of course, is multifold:

1. the market is in turmoil. No one can predict what will happen in publishing over the next few years, so it's hard to come up with definitive answers to prove or disprove

2. a lot has come to light lately about publishers treating authors badly (the Leisure Fiction/Dorchester Publishing fiasco being only one example), so a "tear down the gates" mentality is definitely simmering, for good reasons

3. self-publishing HAS become much, much easier, quicker, and cheaper. And we here in America generally like things easier, quicker, and cheaper (and notice, I didn't say GOOD self-publishing. Just self-publishing)

And here's the one that gets under my skin the most:

4. several authors with built in audiences - which, I'm assuming, they built through traditional publishing - turning around and telling all us new writers that if we don't self-publish RIGHT NOW, we're all short-sighted, missing out, foolish for not earning all the instant cash they're earning.

Anyway, I can't tell you what I think is RIGHT or WRONG in self-publishing. I can only share my take, and what I plan to do, assume there are lots of writers out there in my position, who may or may not take something away from me sharing my ideas.

Now, first: I've taken some time to peruse some self-published works, most notably by Robert Swartwood and Dan Keohane. Both works that I read - Man of Wax and Margret's Ark - were top-notch. So much so, I have two more self-published works by both these authors sitting in my TBR pile, and will continue to buy more from them. Haven't read them yet, but I think Glen Krisch and Richard Wright's will probably be top-notch also.

Now, with these new-fangled self-publishing times, technically, there's nothing stopping me from publishing my novel soon as I'm finished with it, and joining these guys in the ranks.... except I'm NOT in their ranks, yet. And here's why:

1. I haven't done my time yet: these guys have been around for awhile. And yes, maybe if self-publishing had been cheaper ten years ago, they might not have waited so long to publish. But these guys have been knocking on their respective doors in publishing for a LONG TIME. I've just begun to knock. How can I possibly know if traditional publishing is really for me if I don't TRY it first?

Almost a year ago, Norman Partridge posted a blog along these lines - though he was also talking about micro-small presses - and he asked a very simple question that set me back on my heels: Have you really tried (traditional publishing)? And these guys HAVE. I haven't.

2. They've amassed a body of work that I HAVEN'T: And during all this time, these guys - I'm assuming - have been writing and re-writing several drafts of different novels, not only doing their best to get them out there - through agents and such - but also rewriting those novels, polishing them, in pursuit of excellence.

So, they've actually gotten several novels under their belt. I'm still writing my first, while a half-finished second languishes in a box. What do I have to self-publish that's been drafted and redrafted, cut, edited, vetted, and critiqued? What do I have that's made all the rounds? Nothing.

3. Jumping off number 2, these guys have street cred: they've done enough in the field, and have written quality enough work to get blurbed by some of the best in the business. I'm nowhere near there, yet. And maybe that's not necessary to self-publish. But I can tell you, most self-published books I'd never buy. But I risked it on Dan's work because I'm familiar with his short work, and he's got good "street cred" because of that. And, because I'd read his first, traditionally published novel. And, Robert's novel was blurbed by F. Paul Wilson.

I have very little "street cred". What's going to make my work stand out? NOTHING.

4. Finally...I CAN'T AFFORD IT. Traditional publishing is actually a much better choice for me - and, I'm assuming, a lot of other writers like me - because to self-publishing the RIGHT way, not only does it take the same time and patience and re-writing that any fiction takes, it takes MONEY and investment.

I can't speak from experience, but from this: as a self-published book, Man of Wax was put together nicely. Very nice cover and graphic design, it had clearly been edited, the layout and font and all that wasn't inferior to a traditionally published novel in any way. Same thing for Margret's Ark.

And that takes MONEY. For Adobe Invision, to commission cover art, to pay for layout and design, to pay an editor, then pay the fees to publish it on Amazon, buy the ISBN....and yes, it's an investment, true....one that a person like me has NO GUARANTEE of ever seeing a return on. Maybe I'll be one of these "overnight" sales successes that gush all over Facebook about themselves.

Most likely, I'll earn NEXT TO NOTHING. And, I'll have to pay all that over again for the next book, with the same risks.

And you know what? I'm willing to bet there's plenty of writers out there in the same position as I am. Which makes traditional publishing - and all the headaches involved - far more worth the effort in the end. Either way, if I'm not guaranteed a success, I'll pick the option that won't cost me money. Right now, being published by Shroud, Cemetery Dance, Apex, Samhain, Angry Robot, Abbaddon Books, Medallion Press FAR outweighs self-publishing, for that fact (and many, many others), alone.

**ATTENTION! SNARK ALERT! EASILY OFFENDED FOLKS, TURN BACK NOW!**

Also, too, I'm kinda getting sick of this refrain: "Oh, the BIG SIX will never let you in, and they're heading for a downfall, baby...."

Blah, blah. The Big Six aren't the only options for traditional publishing. There are tons of midlist houses out there, and yeah, many of them are owned by the Bix Six, and there's big and mean old Ingram Distribution as well....but this constant refrain always strikes me as lots of complaining. It's like the guys back when I played basketball who either wanted to start and be the leading scorer, or nothing at all. Instead of sitting the bench or being the sixth man or a role player, they'd take their ball, go home, and play pick-up on the court behind Wal-mart.

Because they didn't want to do their time. Wait their turn. And yeah, this is a little snarky, hence the above warning. But I just can't shake a feeling of annoyance at those arguments. Someone like Robert Swartwood? He did his time. Made the rounds with all the publishers, worked his ass off, and AFTER that decided self-publishing was his route. AFTER doing his time.

And I guess all these complaints about these evil New York houses and their abusive editors don't wash with me (and yeah, I have next to no experience in that area, so I really wouldn't know). Maybe I got lucky, but my interactions with an editor at HarperCollins were friendly, professional, and very helpful.

Even though her boss turned down my pitch because the "sales team didn't get it", no hard feelings. In fact, the story wouldn't be where it is today without her pushing and prodding me in different directions. But, as soon as it looked like we didn't have any further to go together, did I cry "foul", grab my ball, go home and self-publish? NO.

And again, maybe I've got to get screwed over a few more times. Who knows. But I'm one of those old fashioned folks who believe that getting told "No" is sometimes very, very important...and always for a reason.

Anyway, rant done. That's why for me - and, I'm willing to bet, for lots of other writers like me, out there - self-publishing just isn't the great deal lots of people are making it out to be...

Published on March 12, 2012 14:50

March 9, 2012

The General and Universal Theories of Horrific Appeal - It's All About the Story

To be honest, I feel like my last post about Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, "Attraction to Monstrous Power & Psychoanalysis" was pretty weak. It was right after school, and I'd forgotten about the psychoanalysis part, wanted to skip it and go straight to this, but didn't want to leave anything out. Then, I was left with a blog post that didn't seem nearly long enough, but too long to add in Carroll's actual theories on "horrific appeal".

To be honest, I feel like my last post about Noel Carroll's The Philosophy of Horror, "Attraction to Monstrous Power & Psychoanalysis" was pretty weak. It was right after school, and I'd forgotten about the psychoanalysis part, wanted to skip it and go straight to this, but didn't want to leave anything out. Then, I was left with a blog post that didn't seem nearly long enough, but too long to add in Carroll's actual theories on "horrific appeal".So here it is, today. Carroll's answer as to why so many folks are attracted to horror, drawn to something that scares, terrifies, disgusts, or repulses them. Why we seek those things out - both in print and on screen - and, in my own addendum, why horror writers labor in this field to begin with.

First, Carroll begins by relating horror to tragedy, riffing off Hume and Aikins' take on Aristotle's Poetics, (and that just tickled me so much I ordered it, for myself). The question they asked was, like Aristotle in regards to tragedy, how it's possible for audiences to derive pleasure from any genre whose objects cause distress and discomfiture (pg. 179)? In real life, these things would be distressing or displeasing.

So why? Why seek them out in art and fiction?

Carroll makes an excellent point before getting into the meat of things; that, for the most part, like tragedies, horror generally takes a narrative form. So, because of this, Carroll suggests that - though important ingredients in the formula - it's NOT the monsters or objects of terror that interest us, that we derive pleasure from, but that the narrative itself holds the most interest for us.

In other words, as always.....

It's all about the story.

So, according to Hume, audiences don't take pleasure in bad things happening, but rather we're interested in the rhetorical framing for these events, we derive pleasure in watching events unfold towards an unknown conclusion. In other words - using tragedy here as an example - the interest audiences take in the deaths of Hamlet, Gertrude, Claudius, or even Romeo & Juliet, is not sadistic, but....

So, according to Hume, audiences don't take pleasure in bad things happening, but rather we're interested in the rhetorical framing for these events, we derive pleasure in watching events unfold towards an unknown conclusion. In other words - using tragedy here as an example - the interest audiences take in the deaths of Hamlet, Gertrude, Claudius, or even Romeo & Juliet, is not sadistic, but...."...is an interest that the plot has engendered in how certain forces, once put in motion, will work themselves out. Pleasure derives from having our interest in the outcome of such QUESTIONS satisfied." (pg. 179)

So, connecting this to horror: it's not the tragedy or the death or the object of horror audiences and readers are attracted to, it's how well these things are worked into the story's narrative, and how they are resolved. Carroll has been building up to this point, because throughout the work, he's analyzed the different narrative structures of horror film and fictions, and he's found this:

"...these stories (horror), with great frequency, revolve around probing, disclosing, discovering, and confirming the existence of something that is impossible, something that defies standing conceptual schemes. It is part of such stories - contrary to our everyday beliefs about the nature of things - that such monsters exist. And as a result, audiences expectations revolve around whether this existence will be confirmed in the story." (pg. 181)

Because, according to Carroll, the center of the horror fiction is something that is unknowable, something which cannot exist, given our acceptable schema for the world. So, according to Carroll, the real drama in a horror story resides in establishing the existence of the monster and in disclosing its horrific properties. Then, once this has been done, the monster must be confronted, so the narrative is then driven by the question as to whether or not the creature can be destroyed.

So, leaping from this, Carroll posits:

"...these observations suggest that the pleasure derived from the horror fiction and the source of interest in it resides, first and foremost, in the processes of discovery, proof, and confirmation that horror fictions often employ." (pg. 184)

In other words, Carroll believes we're attracted to the majority of horror fictions because of how the plots of discovery and the dramas of proof intrigue us. Arouse our curiosity. Abet our interest, in ways that are satisfying and and pleasurable.

He makes a point here to mention that feeling disgust is an integral part of this process. In other words, monsters in these types of tales must be disturbing, distressful, or repulsive on SOME LEVEL, if the process of their discovery is to be rewarding in a pleasurable way. It's not that we crave disgust, according to Carroll, but that disgust is just something that happens naturally in the disclosing of the unknown - whose disclosure is a desire the narrative instills in the audience, then proceeds to satisfy.

And for that desire to know about the unknowable - the monster MUST be unknowable in some way, or impossible, or the familiar warped into the repulsive - so that the monster defies our conception of nature.

So that basically, Carroll's General and Universal Theories of Horrific Appeal spin on the idea that because the majority of horror fictions are narrative-based stories bent on discovering unknown or unknowable things, that even as audiences are necessarily disquieted or distressed or even disgusted and repulsed by the revelation of these things, we are drawn to how these things unfold within the structure of the narrative, our desire to know is what draws us into these stories, and that - like with Hamlet's death - we aren't sadist and violent and depraved in consuming different types of horror, we simply want to discover, to know, to see how it all ends. We are fascinated with the process of the investigation, exploration, discovery, and then - if possible - overcoming of unknowable, impossible things. **

So. Tomorrow or Sunday, on to my final look at this, Noel Carroll's sections entitled "Horror and Ideology" and "Horror Today."

**Carroll does make a point that it's very likely some folks seek horror fictions out for their gore and violence and bloodshed, once again, not because they're demented sick freaks, but because they perceive viewing these films as an endurance test, a test of their "courage" or "manhood." He, however, does not believe this to be largely the case, and also believes that those types of movies NOT be held up as a standard for horror in general.

Published on March 09, 2012 03:05

March 8, 2012

Final Reflections on "The Philosophy of Horror", Part Three: Attraction to Monstrous Power & Psychoanalysis

I was thinking this would be my final post on this subject, but seeing as how Carroll ends his work The Philosophy of Horror with a section sub-titled "Horror Today" that mixes in some discussion of post-modernism, I may have to save that for a separate, fourth and fifth post, because its implications intrigue me, and may or may not hold the center-pinning for my paper this semester.

I was thinking this would be my final post on this subject, but seeing as how Carroll ends his work The Philosophy of Horror with a section sub-titled "Horror Today" that mixes in some discussion of post-modernism, I may have to save that for a separate, fourth and fifth post, because its implications intrigue me, and may or may not hold the center-pinning for my paper this semester.So in review, Carroll critiques three solutions that are often offered as to the paradox of why people enjoy horror. The first solution he critiques is Lovecraft's treatise on cosmic fear, which he essentially rebuffs because while acknowledging that it certainly holds works of horror to a very high standard, it cannot be used as a summation of ALL that is horror. Then, he examines Rudolf Otto's ideas of religious awe, disbelieving this explanation as misapplied, because very rarely does this monstrous thing that stupefies us, holds in trembling awe ALSO become a thing we feel the need to pay homage to, show devotion.

The third solution he critiques is the following, one he says may often be connected with the solution of religious awe: is that horrific beings attract viewers because of their power.

Carroll clarifies things like this; these monstrous beings - like in religious awe - induce awe, and we identify with monsters because they're powerful, maybe even making monsters wish-fulfillment figures. And in some cases, Carroll feels this explanation serves nicely. He cites Melmoth the Wanderer, Dracula, and Lord Ruthven as monsters whose powers are very seductive - both in nature, and the lure of being as powerful as they.

Again, however, Carroll cites that this explanation is simply not broad enough to fit the whole genre. What about rotting, muttering, cannibalistic and brainless zombies? Slime monsters? Mutated insects? Carroll goes so far as to assume that these and many other horror tropes are not exactly wish-fulfillment figures.

Psychoanalysis:

Carroll also address the method of applying psychoanalysis to horror films, but I'm going to only briefly mention that here, simply because - like the other solutions he critiques - psychoanalysis, with its heavy reliance on unconscious sexual urges or unconscious wish fulfillment, simply doesn't apply to horror in general, or very well at all.

Essentially, Carroll asserts the same thing about psychos analysis in relation to horror as he's said concerning these other solutions - it applies well to certain movies and books and certainly may give greater insight into those particular work and sub-genres, but it's too much a stretch to attach repressed sexual desires and repressed fantasies and wish-fulfillment scenarios to horror cinema in general.

Carroll cites this problem in particular with a psychoanalytic look at horror: that very often, these repressed urges must be understood to be in some way sexual, and it's very hard to apply that to every movie monster ever to grace the screen, because for a "hardline Freudian" (his terms) everything must come back to a sexual act, which is simply too hard to apply to all horror movies.

Carroll does offer some wiggle-room for things like repressed anger or anxiety or fears, suggesting that if this theory wasn't bound by its insistence on sexual meanings, the scope widens a little bit. He asserts that movies like The Excorcist, Carrie, The Fury and Patrick - all movies that feature telekinetic powers activated by emotions and stress or anger or possession - could gratify a repressed, infantile rage.

But, Carroll ultimately comes to the conclusion that sometimes in horror cinema and fiction, monsters are just monsters, and that's all.

Sometime Saturday I'll post Carroll's own solution to this paradox, something he calls The General and the Universal Theories of Horrific Appeal.

Published on March 08, 2012 14:11

March 4, 2012

Final Reflections on "The Philosophy of Horror", Part Two: Religious Awe

One of the second solutions to the "paradox of horror" that Noel Carroll critiques in

The Philosophy of Horror

is this: that the horror genre compels our interest as readers, viewers, and writers because it invokes in us a sense of religious awe.

One of the second solutions to the "paradox of horror" that Noel Carroll critiques in

The Philosophy of Horror

is this: that the horror genre compels our interest as readers, viewers, and writers because it invokes in us a sense of religious awe.Carroll draws from Rudolf Otto's The Idea of the Holy, (what looks like a good synopsis of it can be found here), which offers an analysis of something called a "numinous experience":

numinous experience: an English adjective describing the power or presence of a divinity ; which has two aspects: mysterium tremendum, which is the tendency to invoke fear and trembling; and mysterium fascinans , the tendency to attract, fascinate and compel.

The numinous experience also has a personal quality to it, in that the person feels to be in communion with a wholly other. The numinous experience can lead in different cases to belief in deities, the supernatural, the sacred, the holy, and/or the transcendent. (from Wikipedia).

So, according to Carroll's reading of Otto, an object of religious experience (something like God, or Other) is tremendous, causing fear in the subject, a paralyzing sense of being empowered, or being dependent, of being nothing, worthless (pg. 165). In other words, this object - the numen - is awe-ful, resulting in a sense of awe.

The numen is also mysterious; it is wholly other. Beyond the sphere of the usual, the intelligible, and the familiar. And, according to Carroll's reading, this not only FREAKS us out, on a very primal level, it also fascinates us with its mysterious otherness (and right now, all Repairman Jack fans are looking very interested, I bet).

Carroll definitely admits the validity of these ideas, because lots of art-horror objects have power: they are fearsome, engender a sense of being overwhelmed, mysterious because they don't "fit in" with our world schema, rendering us dumb, trembling, astonished, paralyzed by their "otherness".

Here again, however, Carroll points out two issues he has with this idea, when applied with broad strokes to the horror genre:

1. Like Lovecraft's treatise on cosmic fear, Carroll feels that the idea of the numinous experience and religious awe is too narrow to apply to all works of horror. In fact, he quibbles with the idea that monsters of horror need always be Other. In many cases, they are. The alien, forbidding concept of "Other" is a powerful theme running through many works of literature, from the aforementioned Repairman Jack series - in Jack's involvement in a cosmic battle between the Otherness and the Ally - to Lovecraft's works, even works like Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Willian Dafoe's Robinson Crusoe, though in those cases, Other takes on very primal, perhaps even racist (in regards to anything OTHER than white European colonialism) overtones.

But Carroll balks at the idea that this "otherness" should be applied to most horror monsters. Once again, this can be very subjective, depending on one's definition of a "monster", but according to Carroll's work, the "monster" in horror is not necessarily horrifying because it is "other", but horrifying because it is the familiar warped and twisted, which derives its repulsive aspect from:

"being...contortions performed upon the known. They do not defy prediction, but mix properties in nonstandard ways. They are NOT wholly unknown, and this is probably what accounts for their characteristic effect - disgust." (pg. 166)

Which makes a lot of sense. Many times in books and movies, something is horrifying because it is the familiar or trusted made menacing and terrifying. One Lovecraft story I can think of, off the top of my head, that focuses more on this than cosmic fear and "Other" is What the Moon Brings , a creepy little short story based on the idea that the friendly and the normal is warped and changed and made terrifying by the light of the moon. There are plenty of other, more modern examples - I believe that Charles L. Grant's Oxrun Station novels invoke this terrifying sensation of the usual twisted into something warped and threatening, though there's a good dose of a frightening Other at work there, also.

2. Carroll's second issue with the idea of a numinous experience being applied to horror in general is this concept of tremendum, which, according to him, compels not only fascination, but also homage. He doesn't feel this fits horror well at all, and this makes a lot of sense. We - and protagonists - may feel helpless in the face of horror objects, but we don't necessarily feel worthless, like nothing - dependent - before an object of horror as we would necessarily feel before a deity. Unless, of course - and this is my addition to the conversation - the horror story itself is designed as an indictment against religious and Other beings, which, once again, brings Repairman Jack to mind, because Jack is forced to comply with the Ally, serve Its purposes (ergo, pay homage), because the Other is so much worse, and because the Ally simply gives Jack no choice in the matter.

2. Carroll's second issue with the idea of a numinous experience being applied to horror in general is this concept of tremendum, which, according to him, compels not only fascination, but also homage. He doesn't feel this fits horror well at all, and this makes a lot of sense. We - and protagonists - may feel helpless in the face of horror objects, but we don't necessarily feel worthless, like nothing - dependent - before an object of horror as we would necessarily feel before a deity. Unless, of course - and this is my addition to the conversation - the horror story itself is designed as an indictment against religious and Other beings, which, once again, brings Repairman Jack to mind, because Jack is forced to comply with the Ally, serve Its purposes (ergo, pay homage), because the Other is so much worse, and because the Ally simply gives Jack no choice in the matter.But anyway, according to Carroll, we - and characters - don't often feel compelled to pay homage to the monster, or at least often enough to make this solution broad enough to fit horror in general. He certainly admits that in many works, cults or nefarious groups may pay homage to a monster to raise it from the dead, or bring about the destruction of the world, but these elements are only part of the story, and - from my perspective - these folks usually are not the protagonists, with whom most audiences feel the most sympathy for.

Again, one thing that's impressed me about Carroll's work is its breadth and meticulous critical analysis. Also, his balance is to be admired. He doesn't shoot down these ideas from his own opinions or beliefs, he's worked hard to maybe do the impossible - find an explanation that fits the horror genre in totality - and he certainly doesn't dismiss these solutions as worthless or without merit. He simply, very logically, points out the problems he believes exist in the broad applications of these ideas.

That religion, spirituality, or belief in some higher power influences horror fiction and film isn't a surprise. For many viewers and readers and especially writers, the consumption or creation of supernatural horror as an inspiration of, an homage to, or way of exploring the realm of the supernatural, spiritual, even the holy makes sense. Supernatural horror, tales of dread, whatever they're called, deal primarily with the unseen world. Faith, spirituality, and religion accept the unseen world as a given. The two go well together, hand in hand.

The internet and literature abounds with very reasoned, logical studies of the relationship between horror and religion. Author Mike Duran blogs about this relationship often, his most recent posts on the topic being: "The Apologetics of Horror", "What's the Difference Between "Classic" and "Contemporary" Christian Horror?", "On 'Christian Horror' and Atheist Dread", and a pretty unflinching indictment that "evangelical" horror falls short of actually inspiring any terror or dread in, "Why Christian Horror Is Not Really Scary". Critically acclaimed author and essayist Matt Cardin also blogs about religion and horror at The Teeming Brain.

TheoFantistique featured this review of a Rue Morgue article about "The Rise of Christian Horror", and another post entitled "Christianity and Horror Redux: From Knee-Jerk Revulsion to Critical Engagement". Academic studies such as The Sanctification of Fear: Images of the Religious in Horror Films are widespread and common. I'm eagerly awaiting the arrival of Sacred Terror: Religion and Horror on the Silver Screen , which I'll be reading as part of my studies this semester.

But I agree with Carroll's assessment that the idea of "religious awe" doesn't hold well for the horror genre as a whole, especially for that second reason: if the "numinous object" is what holds terror and dread for us, holds us in fascination, it doesn't work for horror that features monsters or demons or beings that threaten and menace protagonists, because the protagonists don't revere it the same way it appears that Otto says someone focused on a "numinous object" would.

Also, too, I'd assert there's a vast difference between horror fictions in which religion and spiritual matters are important and central, and horror that pushes the reader in a certain direction with an evangelical thrust. For example, in my opinion, there's a huge difference between William Peter Blatty's classic novel The Exorcist and the Left Behind Series , a story of earth's last days, inspired by the Book of Revelations.

The Exorcist is quite definitely a tale faith and the struggle between good and evil. But it's thrust doesn't seem to be the ultimate conversion of the reader, which is something that becomes a stronger and stronger vibe throughout the Left Behind series.

I don't want to get off topic on this. A post about my feelings concerning Christian Fiction in general and Christian Horror in particular could be a post all by itself. Suffice to say, there's a big difference between a horror story pitting supernatural evil against supernatural good, or a horror story dealing with loss of faith, the struggle to believe, and a horror story that's more a cautionary tale, a "if you're not a good Christian and don't act a certain way, say the right words, accept Jesus into your heart, you're going to hell."

An excellent alternative to the Left Behind series is Brian Keene's novella (I swear, he's not paying me to pimp him so heavily. His books just keep jumping to mind) Take The Long Way Home. It's about four men caught in the middle of the chaos and aftermath of the Rapture. The difference between this work and Left Behind and others of its ilk is the story struggles and grapples with matters of faith and belief, rather than treating them as assumed, foregone conclusions.

An excellent alternative to the Left Behind series is Brian Keene's novella (I swear, he's not paying me to pimp him so heavily. His books just keep jumping to mind) Take The Long Way Home. It's about four men caught in the middle of the chaos and aftermath of the Rapture. The difference between this work and Left Behind and others of its ilk is the story struggles and grapples with matters of faith and belief, rather than treating them as assumed, foregone conclusions. Interestingly enough, something like Take The Long Way Home and other stories like it actually come very close to the concept of "religious awe" as Otto and apparently Carroll define it, because in this case, the "monster" that causes all the violence and bloodshed is "God" - by calling all His believers home, leaving others behind to suffer.

But, at the same time...this is God. How can the characters not revere him and at least grapple with the concept of paying homage to Him, at the same time that they dread Him?

A short story that also deals with this concept - but from a different angle, that of an avowed unbeliever facing certain death by defying a God who has finally come down to earth to rule - is "He Who Would Not Bow", by Wrath James White, in a horror anthology about faith and gender, Dark Faith.

Anyway, I feel I've rambled a little too much on this one, possibly because despite Carroll's disqualification of "religious awe" applying to the horror genre in general, it's obvious that religion and horror are intimately linked. In any case, tomorrow I'll look at Carroll's third critique of a possible solution to the "paradox of horror", attraction to the power of monsters.

Published on March 04, 2012 13:30

March 3, 2012

Final Reflections on "The Philosophy of Horror": Part One

"The question is: why would anyone be interested in the genre (horror) to begin with? Why does the genre persist.....how can we explain its very existence, for why would anyone WANT to be horrified...?"

"The question is: why would anyone be interested in the genre (horror) to begin with? Why does the genre persist.....how can we explain its very existence, for why would anyone WANT to be horrified...?" "Furthermore, the horror genre gives every evidence of being pleasurable to its audience, but it does so by means of trafficking in the very sorts of things that cause disquiet, distress and displeasure.

So...why horror?"

- Noel Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror, pgs. 158 - 159.

So I'm finished with the first book I've read for my proposed paper on the development of horror cinema and horror cinema today, The Philosophy of Horror, by Noel Carroll. Overall, it was an excellent work. Very comprehensive, thought-provoking, and illuminating. I'm going to review Chapter Four, "Why Horror?" - in three separate blog posts, because they're so long - then tag on some additional thoughts at end.

To this point, Carroll has worked to find a definition of horror, pondered the connection between the audience and protagonists of horror films, the varied ways horror films and fictions are plotted, and then ends by coming back to the essential question: why? Why watch and read horror, why write it...why does it exist, and why is it so popular?

Early on in the chapter, Carroll does point out that there are some who are simply attracted to blood and guts and gore, and that's all there is to it. He cites that the reasons here are possibly voyeuristic, but more than likely they can be viewed as a "rite of passage" - the manly thing to do. In other words, if you can survive back-to-back viewings of all the Hellraiser movies, then you're made of "tough stuff", have a "strong stomach", and have achieved a sort of "pseudo-bravery".

Early on in the chapter, Carroll does point out that there are some who are simply attracted to blood and guts and gore, and that's all there is to it. He cites that the reasons here are possibly voyeuristic, but more than likely they can be viewed as a "rite of passage" - the manly thing to do. In other words, if you can survive back-to-back viewings of all the Hellraiser movies, then you're made of "tough stuff", have a "strong stomach", and have achieved a sort of "pseudo-bravery".He points out, though, that he's not interested in that demographic, and that well-done horror films do not go for the gross-out only, and that he's analyzing well-done films only. Of course, one's idea of well-done can be subjective, but he at least sets down a framework for what he considers to be a well-done horror movie: a film designed to invoke emotions in the viewer, among the following:

1. fear

2. dread/horror/terror

3. disgust/revulsion

...and that movies hitting #3 only are not horror films, per se. He doesn't offer a title for films that focus on that latter only, so I won't either...because I'm still threshing that out in my head, too.

In the section subtitled The Paradox of Horror, Carroll comes to this resolution:

"Thus, the paradox of horror is an instance of a larger problem...that of explaining the way in which the artistic presentation of normally aversive events and objects can give rise to pleasure or compel our interests." (pg. 161, emphasis mine).

He focuses his efforts on the following three explanations for why horror compels our interest as readers, viewers, and...by my extension...writers:

1. cosmic fear

2. religious awe

3. attraction to the power of monsters

Cosmic Fear

:

Cosmic Fear

:Here, of course, Carroll cites the father of cosmic fear himself, H. P. Lovecraft:

"The one test of the really weird is simply this - whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes on the known universe's utmost rim."

and...

"When to this sense of fear and evil the inevitable fascination of wonder and curiosity is super-added, there is born a composite of keen emotion and imaginative provocation whose vitality must of necessity endure as long as the human race itself."

So, according to Lovecraft - as Carroll sums it up - humans are born with an instinctual fear of the unknown which verges on awe. This, perhaps, is then the attraction of supernatural horror: That it provokes a sense of awe which confirms deep-seated human convictions about the world, that it (the world) contains unseen forces, and that the literature of cosmic fear attracts us because it confirms these deep-seated fears of ours, creates an apprehension of the unknown, charged with wonder.

Speaking as a reader and moderate viewer of horror cinema, there's a lot to vibe with, especially this bit:

"that literature of cosmic fear attracts us because it confirms these deep-seated fears of ours, creates an apprehension of the unknown, charged with wonder."

For me, personally, as a reader and a writer, it is the supernatural unknown that fascinates me. Obviously this connects with my spiritual background and beliefs, but even so, the idea that we walk in a very modern, materialistic world while unseen forces swirl around us, constantly in conflict - ergo, the eternal battle of Good VS. Evil - strikes a deep resonance within me not only of interest, but of Ultimate Truth, also.

Probably why Stephen King, Dean Koontz, and Peter Straub - and also now Charles L. Grant, Norman Prentiss, T. L. Hines, Mary Sangiovanni, T. M. Wright (to name only a few) - are among my favorite authors, because they write so often in this vein, and, quite frankly, it's the kinda stuff I want to write about, too.

Carroll, however, points out two very insightful flaws with Lovecraft's position:

1. nowhere in his horror manifesto does Lovecraft seem to identify why experiencing this cosmic fear would be a good thing, or so fervently sought out. Carroll posits that perhaps Lovecraft believed it an essential part of what it is to be human - our way of responding humanly to the world - or a corrective to the "dehumanizing encroachment of materialistic sophistication" (pg. 162). This sounds very plausible, but because Lovecraft never takes the time to address this, Carroll can't accept his argument wholesale.

2. that Lovecraft, in his opinion, confuses what he regards as a level of high achievement in the genre with what identifies the genre. To clarify, Carroll says that Lovecraft's assessment really only targets commendable, well-done horror - or a certain type of horror - and not the horror genre itself.

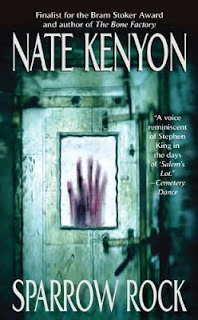

And this bears out in my own reading. For example, Charles L. Grant's brand of dark fantasy - what I've read - loves to traffic in this sense of "cosmic dread" or "fear of the unknown". And I love all his work. But Nate Kenyon's

Sparrow Rock

is a WONDERFUL work that is completely about human horrors, while The Reach - also by Nate - is certainly more "spiritual", but still about human unknowns, not necessarily cosmic unknowns. And they're both FABULOUSLY well written.

And this bears out in my own reading. For example, Charles L. Grant's brand of dark fantasy - what I've read - loves to traffic in this sense of "cosmic dread" or "fear of the unknown". And I love all his work. But Nate Kenyon's

Sparrow Rock

is a WONDERFUL work that is completely about human horrors, while The Reach - also by Nate - is certainly more "spiritual", but still about human unknowns, not necessarily cosmic unknowns. And they're both FABULOUSLY well written.And some authors can produce both kinds of works. Brian Keene regularly does so. The Rising, Dead City, Dark Hollow, Ghost Walk, A Gathering of Crows, Darkness on the Edge of Town, Terminal and even Ghoul could be said to traffic in "horrors of the unknown beyond our world". His novella Take the Long Way Home , fits nicely Carroll's second category, "religious awe". However, three really excellent examples: His novella Jack's Magic Beans and the novels Urban Gothic and Castaways certainly hit all of Carroll's requirements for horror, but aren't supernatural in any way, and are all excellent reads.

Robert Dunbar's best two works (IMO): The Pines and The Shore are, again, about human and biological/genetic unknowns, but they're beautifully written, about hurting, conflicted characters. They - despite their high quality - also don't fit into Lovecraft's definition.

Another author who traffics in both would be Dean Koontz. A lot of his works - especially his later works - deal with unknown forces, though he clearly separates them into Good VS. Evil. His Odd Thomas and Frankenstein series comes to mind. One Door Away From Heaven. And too many others to name. Night Chills and Shattered, however - though still about Good VS. Evil - are completely rooted in human dynamics. So, even based on my own reading, I definitely see where Carroll is going in his questioning Lovecraftian's definition of the horror genre as a whole.

Tomorrow, I'll look at Carroll's critique of the second solution to the "paradox of horror", "religious awe".

Published on March 03, 2012 18:03

February 29, 2012

New (Old) Story Available...My First Kindle....

Ironically enough - or perhaps not - even as I've settled myself concerning the digital revolution (still grappling with the issue of self-publishing, of course), my first "release" comes in digital format.

I don't write flash fiction much. Hardly at all, and sometimes I don't know what to think of flash fiction in general. I read some flash stories and think: "That's hardly a story at all", then read others and marvel: "How DID they fit all that in there?"

Suffice to say, it's not a form I write in much. But the one or two pieces I have written have landed whole, with very little editing needed regarding story, just grammatical elements. One of them, "Old Bassler House", a life-inspired story, can be found in Shroud Publishing's Northern Haunts .

My most "recent" flash story (I say recent, because it was written in 2009), "Black Dog Whispers", is now available in the kindle collection New Bedlam: Town Archives. New Bedlam is a cool little fiction project, about a town cursed with never-ending insomnia. So all the stories offer snap-shots of folks living in this town...as they stumble around, dead tired but unable to sleep...ever.

My most "recent" flash story (I say recent, because it was written in 2009), "Black Dog Whispers", is now available in the kindle collection New Bedlam: Town Archives. New Bedlam is a cool little fiction project, about a town cursed with never-ending insomnia. So all the stories offer snap-shots of folks living in this town...as they stumble around, dead tired but unable to sleep...ever.

Anyway, the Kindle version is here. However, the folks running New Bedlam are hoping to generate enough orders for a limited edition print run, so if you think you'd like a print version, order here.

I don't write flash fiction much. Hardly at all, and sometimes I don't know what to think of flash fiction in general. I read some flash stories and think: "That's hardly a story at all", then read others and marvel: "How DID they fit all that in there?"

Suffice to say, it's not a form I write in much. But the one or two pieces I have written have landed whole, with very little editing needed regarding story, just grammatical elements. One of them, "Old Bassler House", a life-inspired story, can be found in Shroud Publishing's Northern Haunts .

My most "recent" flash story (I say recent, because it was written in 2009), "Black Dog Whispers", is now available in the kindle collection New Bedlam: Town Archives. New Bedlam is a cool little fiction project, about a town cursed with never-ending insomnia. So all the stories offer snap-shots of folks living in this town...as they stumble around, dead tired but unable to sleep...ever.

My most "recent" flash story (I say recent, because it was written in 2009), "Black Dog Whispers", is now available in the kindle collection New Bedlam: Town Archives. New Bedlam is a cool little fiction project, about a town cursed with never-ending insomnia. So all the stories offer snap-shots of folks living in this town...as they stumble around, dead tired but unable to sleep...ever. Anyway, the Kindle version is here. However, the folks running New Bedlam are hoping to generate enough orders for a limited edition print run, so if you think you'd like a print version, order here.

Published on February 29, 2012 05:30

February 26, 2012

On Free Amazon Downloads, "Trying out new authors", and Cheerleading

Okay.

Possible rant ahead. Filled with one writer's opinions, and nothing more. We're all in this writing business for different reasons, therefore we have our own goals, our own standards, what makes us happy and content. And maybe I should just file this whole thing under "stuff I see on Facebook and Twitter that annoys me" and leave it at that. But, even if only for myself, I'm gonna grapple with it for a bit, because that's what I'm doing right now: grappling with this whole digital self-epublishing revolution.

So.

Let's start like this:

The other day one of my students - a 10th Grade Honors English student - stalked into my Creative Writing class (which she also takes), looking annoyed. Almost irate. I asked what was bothering her, and she proceeded to go on a mini-rant about all these free or .99 ebooks Amazon keeps offering her Kindle, and after she downloaded them, how her initial excitement fizzled when she realized most of them were either barely comprehensible and "shouldn't have been published at all" or so rife with editing errors, she had a hard time enjoying what she thought might've been a good story.

Now, granted - even as a 10th grade Honors student who's also a voracious reader, maybe she's not that discerning (I know back then I read a lot, and books fell into two basic categories: boring and not boring). Maybe she just missed all the grown-up nuances in those free and cheap e-books.

Or, maybe she just downloaded really crappy self-published ebooks.

I see it on Facebook and Twitter all the time. Probably should just ignore it, and I try to - until I get FB and Twitter messages, all saying a variety of the same things...

"Hey, my buddy's ebook is free on Amazon! And my Grandma's, too!"

"Hey, support indie-publishing! Buy my buddy's ebook, for only .99! Fight the power and join the revolution!"

"Hey, try out new authors today!"

Now.

In an effort NOT to sound like an insensitive jerk. Also trying not to shoot myself in the foot, because hopefully soon - either traditionally or independently - I'll be out there, promoting my work, too.

All writers today need to self-promote. That's pretty much a fact. I do it. When a new story gets accepted and published, when a new review comes in, I post about it. And that's one of the things digital self-publishing has opened new, unproven ground for: author promotion, control over pricing, things like that.

And the big houses in New York - even midlist houses, like that Leisure Fiction fiasco - are engaging in pretty dubious behavior at times, and the removal of the third party, opening the doors for readers straight to writers, is a pretty intriguing wrinkle. Even I can admit that.

And there are lots of great writers whom I love, or writers who've been blurbed by writers I love who are very proactive with their self-promotion in general and Amazon promotion in particular. Folks who have been blurbed by other heavy hitters in the industry, who have earned respect from their professional peers.

This blog isn't aimed at them. They've done their time, proven their worth - if not to me, then to writers whom I respect - and aren't tacky in their self-promotion, like some of the catch-phrases above.

It's just this: I wonder if this whole thing can sometimes be....self-contained.

Self-replicating.

Heck. Incestuous, even.

Because while I see lots of proven writers either going it alone - because they've proven their craft, have been really burned by traditional publishing or have been trying for YEARS (like 10 or so, not a month and half) to crack New York and just haven't - or they're reviving out-of-print works for new digital audiences, I also see a bunch of other writers - some of them proven (a select few), a lot of them NOT - simply supporting this new movement itself. And, that's not bad...in and of itself.

Again. This is probably something I should just leave alone. But it seems like, to me, that while some authors are more than willing to blurb other writers and give them their due, other writers seem to be....turning into cheerleaders for the movement.

In other words, it seems like they're simply supporting every single self-published and for-free digital download on Amazon simply because it's the latest, greatest new thing, reposting and offering up everyone and anyone's free ebook because, well - sure. They're part of the self-publishing digital epublishing revolution themselves. They're rooting for everyone and anyone who's self-published an ebook. And I don't know why, but something about that really bugs me.

Those scores of people who repost ad infinitum offers on Facebook about someone's newly self-published ebook, and the mantra is always the same:

"Hey, support indie-publishing! Buy my buddy's ebook, for only .99! Fight the power and join the revolution!"

"Hey, try out new authors today!"

Now, if you're about ready to pick up something heavy and throw it at me, are cursing my name for how insensitive I'm being and think I hate all indie authors, stop for a minute, breathe, and let me clarify: I'm rapidly and quickly evolving my views on digital self-publishing and self-publishing in general.

I've taken the time to peruse some indie works, and have more coming up the pike soon. And, once I've read those, I'm going to blog my results, share how I think I stack up against those writers, and what I think about ME self-publishing.

What I'm NOT changing any time soon, however, is my commitment to excellence, my standards, my desire to read - and therefore recommend - only what I consider to be high quality work.