Library of Congress's Blog, page 111

May 18, 2017

Story of the Century: My Afternoon with a Jewish American World War II Veteran

The following is a guest post by Owen Rogers, liaison specialist for the Veterans History Project. An extended version of the post appeared on the Library’s “Folklife Today” blog.

[image error]

Schuman in Germany, 1945.

When Burton “Burt” Schuman greeted me at the door with a handshake and an offer of a home tour, he shared his framed Bronze Star Medal and a photograph of himself as a young GI whose smile belied the worn leather of his boots and rifle sling. I had questions about those. But it was the mezuzah on his doorframe that prompted my first and most personal question. Schuman was one of the half million Jewish Americans who served in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II and a veteran of the European Theater of Operations.

I interviewed him when I was a graduate student at Central Connecticut State University’s Veterans History Project. Like the stories of other World War II veterans I interviewed then, Schuman’s oral history is archived both at the Library of Congress and Central Connecticut State’s Elihu Burritt Library.

Schuman ushered me to his basement art studio, where countless images of ducks and marsh life wreathed the walls. He explained that he started developing his artistic talents in college and continued during World War II.

With only one year of coursework under his belt, Schuman became the head cartographer in the G-3 section of the 100th Infantry of the U.S. Army’s “Century” Division. His responsibilities were vast, as he plotted the movement and positions of 100th Infantry forces, developing maps drawn from frontline reports and his own scouting of friendly positions. In our modern era of mobile GPS maps and pin drops, it’s hard to imagine an entire division relying on “maps mounted on four-by-eight plywood . . . on stands . . . [and] on a two-and-a-half ton truck,” as Schuman recounted. For two years, Schuman made that “deuce-and-a-half” [truck] his home.

Although his wartime experiences included encounters with personalities such as General George Patton and Marlene Dietrich, as well as a harrowing 13-hour flight toward friendly lines after his jeep was shot from under him, it was mention of the mezuzah that sparked his most emotional response. Jewish American GIs faced firsthand the horrors of Nazi edicts and extermination. Schuman recalled:

I had full contempt for them, without doubt. I saw many of the German prisoners. . . . [T]hey would march through our command post. I saw a lot of dead Germans on the side of the road, too. It didn’t make me too unhappy, really. I mean that’s going down to the basic thought that I had.

[image error]

Campaign map for the Battle of Heilbronn developed by Schuman in 1945.

I often think of what life must have been like for Schuman in the decades after World War II. Alone in his canoe, painting from life in marshy surroundings. What thoughts weighed on his mind?

Through the insights afforded by Veterans History Project, we’re made more aware of the history held behind his eyes. We owe it to the veterans among our friends, families and communities to ask them questions like the ones I posed to Schuman. Have you taken the time to ask such questions yet? If so, thank you. If not, go here to find out how.

May 17, 2017

From High Style to Humble: Surveying America’s Built Environment

St. Alexander of Nevsky Russian Orthodox Church has a simple wood frame and a gable roof that covers its nave and sanctuary. It is located in Aleutians East Borough, Alaska.

Settlers’ cabins, high-style mansions, jails, barns and churches. These are just a few of the properties the Historic American Buildings Survey has painstakingly documented over the past 80 plus years. The Library started digitizing the survey’s records—many of them stunning and unique—20 years ago, providing public access on its website.

Known as HABS for short, the survey began in 1933 as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Architect Charles Peterson of the National Park Service proposed that the government employ 1,000 out-of-work architects, partly to support recovery from the Great Depression, but also to record America’s architectural heritage, increasingly threatened by the forces of modernization. Peterson wrote:

Our architectural heritage of buildings from the last four centuries diminishes at an alarming rate. The ravages of fire and the natural elements, together with the demolition and alterations caused by real estate “improvements” form an inexorable tide of destruction destined to wipe out the great majority of the buildings which knew the beginning and first flourish of the nation. . . . It is the responsibility of the American people that if the great number of our antique buildings must disappear through economic causes, they should not pass into unrecorded oblivion.

Within weeks of the government’s approving Peterson’s proposal, hundreds of formerly unemployed architects, selected with help from the American Institute of Architects, were busy documenting historical properties through measured drawings, large-format photographs and short historical reports. Thus began America’s first nationwide publicly funded historic preservation program.

[image error]

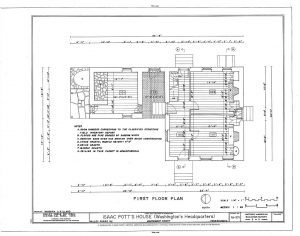

Isaac Potts House in King of Prussia, Penn., served as the headquarters and residence of General George Washington during the encampment of the Continental Army in the winter and spring of 1777–78.

Measured drawing of a room on the first floor of the Potts House, where administrative business of the Continental Army was conducted.

[image error]

View from the salon of Tudor Place in Washington, D.C. The house is an example of the federal-style architecture built in the U.S. between about 1780 and 1815.

Many of the properties first documented reflected high-style architecture. But HABS administrators advised fieldworkers to include buildings not previously considered of interest to the “architectural connoisseur,” such as Native American structures, the “hewn log cabins of the early pioneers,” and buildings in old mining towns. Special priority was to be given to buildings “in imminent danger of destruction.”

The Library of Congress has been a HABS partner from the start with the American Institute of Architects and the National Park Service. The institute advises the survey from the perspective of private-sector architectural practice; the Park Service develops guidelines and produces standard-setting documentation; and the Library maintains the collection and provides public access.

Users of the HABS collection include students, historians and even Hollywood producers aiming to convey the look and feel of an era. Architects often seek out HABS plans and drawings, including for restoration projects for which design details are available only in historical measured drawings.

Building on the success of HABS, the Historic American Engineering Record was founded in 1969 using the same model to document engineering works and industrial sites. The Historic American Landscape Survey was established in 2000 to document historic landscapes. Together, the three collections are among the largest and most popular in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

Still growing, the collections include more than 555,000 measured drawings, large-format photographs and written histories for more than 38,500 historic structures and sites dating from pre-Columbian times to the 21st century. The online presentation features more than 43,000 digitized images of measured drawings, black-and-white photographs, color transparencies, photo captions, written history pages and supplemental materials.

[image error]

The Temple Among the Trees Beneath the Clouds in Weaverville, Calif., is a house of worship used by Chinese immigrants since 1874.

For some time now, students pursuing advanced degrees have produced much of the survey documentation, making the surveys an important training ground for aspiring architects, engineers and historians.

It’s safe to say that Charles Peterson would be more than pleased with the results of what he saw as a temporary make-work program to document threatened properties at a key moment in history. Thanks to his vision and the efforts of thousands of fieldworkers since, we now have a valuable repository of knowledge about the built environment to help tell America’s story.

The Historic American Buildings Survey is highlighted on the website this month under the Library’s “free to use and reuse” feature. As works created for the U.S. government, records from the survey are in the public domain, meaning you are free to use them as you wish. However, material from private sources occasionally appears with the survey records. These materials are noted by the presence of a line crediting the original source. So make sure to check each image before publishing or distributing it.

May 15, 2017

My Job at the Library: Building the Architecture, Design and Engineering Collection

(The following is an article from the November/December 2016 issue of LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine, in which Mari Nakahara, curator of architecture, design and engineering in the Prints and Photographs Division, discusses her job. The issue can be read in its entirety here .)

[image error]

Mari Nakahara. Photo by Shawn Miller.

How would you describe your work at the Library?

Like other Library curators, I am responsible for building the collection. Acquiring new items for the Prints and Photographs Division is very satisfying, but it is also more complicated than one might expect. It requires an in-depth knowledge of the existing collection holdings, Library-wide collection development policies, research trends and rights-agreement issues, among other concerns.

How did you prepare for your current position?

I received a Ph.D. in architectural design and history in my native Japan. My dissertation on McKim, Mead & White, a New York-based architectural firm from the late-19th to early-20th century, required me to access their original documents held in the U.S. The beauty and rich information in those original, historical documents was a powerful magnet that led me to change my career, leaving academia to become an architectural archivist. I received a Fulbright Fellowship that made it possible for me to intern at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural Archives and the Museum of Modern Art. In 2000, I decided to immigrate to the U.S. to pursue my goal of working at an architectural repository, because this profession was not yet available in Japan.

My first full-time job at the American Architectural Foundation brought me to Washington, D.C., in 2003. Four years later, I was hired as a librarian in the Asian Division of the Library of Congress, and I acquired a library science degree at nearby Catholic University of America. I was honored to be hired as the curator of the Library’s architecture, design and engineering collections last year when Ford Peatross, my predecessor, retired after 40 years of service.

What is the size and scope of the Library’s architecture, design and engineering collections?

More than 4 million items pertaining to the subjects of architecture, design and engineering are housed in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division. These include the drawings of many of the most distinguished figures in the field, such as Richard Morris Hunt, the first American architect who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, as well as the innovative furniture and house designs by Charles and Ray Eames from the mid-1900s. Hunt designed significant structures such as the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty and the Biltmore Estate and is considered a leading figure in American architectural history. The Historic American Buildings Survey, the Historic American Engineering Record and the Historic American Landscapes Survey are the most popular design collections. They document sites throughout the U.S. and its territories—ranging from one-room schoolhouses to structures designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

What are some of the most memorable items in the Library’s design collection?

The collection holds many memorable treasures. It is hard to pick a few because each has its own fascinating story. Among the highlights are the competition drawings for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which includes Maya Lin’s winning design. She created her entry at age 21 as an undergraduate student at Yale University. The world of design drawings and photographs constantly surprises people because it covers so many more subjects than one might expect.

May 12, 2017

Pic of the Week: Disco Dance Party!

Gloria Gaynor. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Legendary singer Gloria Gaynor performed the night away in the Great Hall of the Thomas Jefferson Building on May 6 to an audience of dancers in glittering halter dresses, platform shoes, and bell bottoms.

The dance party ended a daylong celebration of disco culture. It started with a symposium that explored disco’s influence on popular music and dance since the 1970s. Gaynor, whose song “I Will Survive” was added to the Library’s National Recording Registry in 2015, talked to Good Morning America host Robin Roberts about her career and what the disco anthem means for her. Other panelists were photographer Bill Bernstein, scholars Martin Scherzinger and Alice Echols, and disco ball maker Yolanda Baker.

A video recording of the symposium is available on the Library’s website.

The dance party concluded “Bibliodiscoteque,” an events series that explored disco culture, music, dance and fashion as told by the national collections.

May 11, 2017

First Drafts of History: Presidential Papers at the Library of Congress

The following is a guest post by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress Gazette, about digitization of presidential papers held by the Library of Congress.

[image error]

An engraving of Franklin Pierce from the mid-1840s. The Library recently placed Pierce’s presidential papers online.

[image error]

An 1853 letter from Pierce to his future war secretary, Jefferson Davis, following the death of Pierce’s son in a train derailment.

The Library of Congress’s presidential papers tell the American story in the words of those who helped write it: through war and peace, prosperity and hard times, from George Washington to Calvin Coolidge.

The Library is currently conducting a years-long project to digitize the nearly two dozen presidential collections in its holdings and place them online—an effort that, when completed, will add more than 3 million images to its online archives and give wider public access to some of the most important papers in U.S. history. A list of the Library’s presidential papers that have already been digitized and placed online is at the bottom of this post.

“These are among our most prized collections. They cover the entire sweep of American history, from our founding to the eve of the Great Depression,” said Janice E. Ruth, assistant chief of the Manuscript Division. “They were preserved and microfilmed for use by the American people, to advance our understanding of our history.”

[image error]

A circa 1850 lithograph of Millard Fillmore based on a Mathew Brady photograph. The Library recently posted Fillmore’s papers online.

The Library recently released the Franklin Pierce papers and the Millard Fillmore papers; the Ulysses S. Grant and James K. Polk papers will be available later in the year.

Those follow the additions of the James Monroe and Andrew Jackson papers in 2015 and Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler and Zachary Taylor last year. The Library digitized and placed online the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Abraham Lincoln more than a decade ago.

In all, the Manuscript Division holds the papers of 23 presidents, from Washington through Coolidge—collections that include some of the nation’s most important and treasured documents: Jefferson’s rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, Madison’s notes on the proposed Bill of Rights, Lincoln’s drafts of the Gettysburg Address and the .

The papers also reveal great figures as ordinary men who, like their fellow citizens, faced personal hardships and heartaches, found and lost happiness and experienced the pains and pleasures of everyday life: Grant composes sweet letters to his wife, Julia; a 13-year-old Washington practices geometry in his school copybook; Jefferson discusses his burial wishes; Theodore Roosevelt confides his suffering in his diary.

“The light has gone out of my life,” Roosevelt wrote beneath a big black X on Feb. 14, 1884—the day both his mother and wife died.

[image error]

A page from George Washington’s school copy book from 1745.

[image error]

Theodore Roosevelt’s diary entry for Feb. 14, 1884.

Pierce experienced terrible tragedy, too. One of his three children died in infancy and another of typhus at age 4. Less than two months before Pierce’s inauguration, tragedy struck again. His last surviving child, Benjamin, was killed in a train derailment, dying in front of his parents’ eyes.

“I presume you may already have heard of the terrible catastrophe upon the rail road, which took from us our only child, a fine boy 11 years old,” Pierce wrote to his future secretary of war, Jefferson Davis. “I am recovering rapidly from my bodily injuries, and Mrs Pierce is more composed to day, tho’ very feeble and crushed to the earth by the fearful bereavement.”

The National Archives and Records Administration, founded in 1934, oversees the papers of presidents beginning with Herbert Hoover. The Library acquired many of its priceless collections before that time, through purchase or donation.

The federal government, for example, purchased Washington’s papers from his great-nephew. Grant’s family donated his in three separate gifts, decades after his death. William Howard Taft deposited his papers at the Library before his death.

In such ways, the Library acquired the papers of most, but not all, of the 29 presidents who served before Hoover.

The Manuscript Division does not hold, for example, the papers of John Adams or John Quincy Adams. And it holds only smaller collections of a few other presidents, such as Fillmore and James Buchanan; those are not counted among the Library’s 23 presidential collections.

In 1957, Congress passed legislation directing the Library to arrange, index and microfilm the presidential papers for distribution to libraries around the country—a massive project that was completed 19 years later.

With the dawn of the digital age, the presidential papers were among the first manuscripts proposed for digitization. The microfilm editions of the Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Lincoln papers were digitized and put online between 1998 and 2005 (an improved version of the Lincoln papers is expected to go online this year).

In 2010, the Library began digitizing the remaining collections of presidential papers—a project that’s ongoing. The final result will be a massive addition of material online: The Taft papers alone encompass more than 785,000 images, the Woodrow Wilson papers nearly 620,000. Even the smaller Polk papers will produce nearly 56,000.

Placing all that material online, Ruth said, is a boon for researchers who in the past might have had to travel to Washington to study the microfilm or arrange for an inter-library loan from a state institution. “Now, we are making them accessible everywhere at anytime.”

Papers of U.S. Presidents Online at the Library of Congress

Millard Fillmore

William Henry Harrison

Andrew Jackson

Thomas Jefferson

Abraham Lincoln (Updated website coming soon)

James Madison

James Monroe

Franklin Pierce

Zachary Taylor

John Tyler

Martin Van Buren

George Washington

May 10, 2017

Inquiring Minds: Researching Jewish Cuisine at the Library of Congress

Award-winning cookbook author Joan Nathan. Photo by Gabriela Herman.

Joan Nathan is the author of 11 cookbooks, including “King Solomon’s Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking from Around the World,” published in April. Her previous cookbook, “Quiches, Kugels and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France” was named one of the 10 best cookbooks of 2010 by National Public Radio and Food and Wine and Bon Appétit magazines. Earlier honors include two James Beard Awards, bestowed for the best cookbook of a given year, for “The New American Cooking” (2005) and “Jewish Cooking in America” (1994). Nathan is a regular contributor to the New York Times and Tablet Magazine.

Nathan will appear at the Library of Congress at noon on May 15 as part of the Library’s celebration of Jewish American Heritage Month. She will speak about “King Solomon’s Table,” sharing stories about her interviews with people from around the world and her research, including her extensive use of Library of Congress collections.

Here she answers a few questions about Jewish cooking and her research at the Library.

What makes food Jewish?

Jewish food is unlike other cuisines like Italian or French food that derives from the land. Jewish food is Jewish if the cook follows the dietary laws or has the dietary laws in the back of her mind. There are two other qualities that determine Jewish food. One is the obsession with food because of the dietary laws. Jews have always been searching for religiously acceptable food from around the world. The third characteristic of Jewish food is the expulsions and relocations of Jews throughout history that made them adapt new local foods to the dietary laws.

When and why did you start researching Jewish food?

When I lived in Jerusalem in the early 1970s, I started seeing the universality of Jewish food. Until then, I was sure that all Jews ate the matzo ball soup, roast chicken and sweet challah that my family had for Friday night. I learned about Moroccan Jewish salads, Kurdish Jewish kubbeh, Aramian soup and so many other exotic and delicious foods.

When did you start using the Library of Congress collections for your research?

I started using the collections for articles for the Washington Post in 1977 and for my second cookbook, the Jewish Holiday Kitchen, which came out in 1979. It was then that I met Myron Weinstein and later Peggy Pearlstein of the Hebraic Section, who steered me to the collection and both helped me greatly in my early research.

What collections have you used?

I have used so many! In the early days, I would spend days reading original documents from the Hebraic collection as well as the European collection of cookbooks, looking for old recipes and memoires that revealed the food eaten by Jews throughout history. As the years went by, I would often get photocopies copies sent to my home.

Which languages do you research in?

Of course, I use English, but I am pretty fluent in French and can read Italian, Hebrew and German.

What are the most interesting finds you have encountered in our collections?

The most interesting have been early recipes in the European collections. Recipes like macaroons repeated themselves, and you repeatedly see recipes for sauce Portugaise that was a tomato sauce, most usually with a Jewish provenance.

What has your experience been like generally researching at the Library?

I love this library, especially the grand reading room and the stacks. There were many years that, on my birthday, I would spend hours in the stacks. This year, on my birthday, I went to the Hebraic Section to listen to Ann Brener, a reference specialist in the section, give a marvelous talk about Rachel Blustein, Israeli poetess and pioneer. All the Library staff have been amazingly helpful to me with manuscripts that could answer my various questions throughout the years.

What dishes might American audiences be surprised to learn are Jewish?

Young Americans today would be surprised to learn that bagels are Jewish as are baked goods like rugelach and babka.

May 9, 2017

Defiant Loyalty: Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers

This is a guest post by Malea Walker, a reference specialist in the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room, about a collection of newspapers published by Japanese-Americans held in U.S. internment camps during World War II. The Library placed the newspapers online on May 5.

[image error]

Roy Takeno (center), editor of the Manzanar Free Press, with other newsroom staff members. Ansel Adams Collection/Prints and Photographs Division.

[image error]

Tulean Dispatch, May 27, 1943

O, what is loyalty

If it be something

That can bend

With every wind?

Steadfast I stand,

Staunchly I plant

The Stars and Stripes

Before my barracks door,

Crying defiance

To all wavering hearts.

—Sada Murayama, Tulean Dispatch, May 27, 1943

In the pages of newspapers published behind the barbed wire of Japanese-American internment camps, one theme stands out: loyalty to the country that placed its own citizens there.

Early issues of the internment camp newspapers are filled with notices of flag-raising ceremonies, ways to help the war effort, ads for buying war bonds and articles encouraging loyalty. “The national emergency demands great sacrifices from every American,” reads one article in the June 18, 1942, issue of the Manzanar Free Press. “By our active participation in defense projects, we must prove our unquestioned loyalty.”

[image error]

Manzanar Free Press, June 18, 1942

[image error]

Tulean Dispatch April 1, 1943

By February 1943, however, a questionnaire was disseminated to the residents of the camps regarding their loyalty to the United States. The question of loyalty was no longer a philosophical one, but one that existed on a government form. Question 28 of Selective Service System Form 304A asked “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

The responses were not all positive. By then, most of the people had been in camps for almost a year, and they had suffered through harsh living conditions in temporary buildings, some of which were not meant for human occupation. Many people had lost businesses and homes. This was not an easy question to answer, and it was debated throughout communities, in families and in the pages of the newspapers. “Did the person who phrased that question ask himself and really try to understand what he was asking,” wrote Shuji Kimura in the April 1, 1943, issue of the Tulean Dispatch.

“Loyalty doesn’t mean saying ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ or extending one’s hand to the flag, or raising a hat or standing up when one hears the ‘Star Spangled Banner’; anyone can do these things. No, loyalty has to be in our hearts and in our memories; it has to be in our fibre and in our bones. Loyalty comes from having lived in America, and having lived deeply.”

American-born citizens of Japanese ancestry, or Nisei, were required to fill out the form as a part of selective service so that they could be drafted. If they answered “yes” to the so-called loyalty questions, Nisei men were also allowed to volunteer for the military. Segregated units were formed, and a great number of young men from the camps volunteered.

[image error]

Topaz Times, March 24, 1943

In a letter to congressmen published in the March 24, 1943, issue of the Topaz Times, one group of volunteers clarified, however, “We are volunteering, therefore, not only because that is the most direct and most irrefutable demonstration of our own loyalty to this country, but because by our action we feel we are contributing to the eventual fulfillment of American democratic tradition in its best and highest meaning.” Reasons for volunteering were varied and complex, not just an act to prove loyalty in the face of internment.

In December 1944, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex Parte Endo that the War Relocation Authority did not have the right to detain loyal citizens. By January 1945, many Japanese-Americans were allowed to return to their homes, but they still faced widespread racism and questions about their loyalty as they integrated back into their communities. They were barred from getting jobs and faced open hostility in the West.

Articles on loyalty changed tone as many Nisei veterans faced these difficulties. The outrage was clear that the loyalty of these veterans was still being questioned. “What more is there to essence of loyalty? What more can they do?” asked Roy Yoshida in the May 2, 1945, issue of the Granada Pioneer.

All of this took place, noted the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1982, despite the fact that not a single incident of sabotage or espionage by citizens or residents of Japanese ancestry was ever found.

May 8, 2017

Photographs Document Early Chinese Immigration

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. This annual recognition of Asian Pacific Americans’ contributions started with a 1977 congressional resolution calling for a weeklong observance. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush extended it to the entire month of May.

At the Library of Congress, Asian American Pacific Islander resources include books, oral histories, personal papers, community newspapers and many other materials housed throughout Library divisions—including photographs that document early Chinese American immigration.

Carol M. Highsmith has recorded the American scene for more than 35 years and donated tens of thousands of photographs, copyright free, to the Library of Congress, available through the Prints and Photographs Division. She has spoken of feeling a sense of urgency to capture aspects of American life that may soon disappear. I suspect she would place in this category her 2012 photographs of early Chinese American settlements that are almost ghost towns today.

[image error]

An abandoned building in Chinese Camp, Calif./Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project.

Chinese Camp in California was one of the largest and most important of these early settlements. Three dozen or so Chinese immigrants from Canton—now known as Guangzhou—arrived there in 1849 to mine gold during the California Gold Rush. The town became known officially as Chinese Camp in 1854, when it got its own post office.

At its peak, 5,000 Chinese immigrants lived in the town, attracted by dreams of riches but also by the safety and comfort of living with others from their home country. Chinese immigrants faced harsh discrimination in the United States, sometimes even physical brutality and worse, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first major U.S. law restricting immigration.

The residents of Chinese Camp did not entirely escape violence, however. The town is also known for an 1856 battle between two rival Chinese factions—or tongs—vying for control. Four men died, and several others were wounded.

After the Gold Rush, the population of Chinese Camp dwindled, and the final settlers left in the 1920s. As of the 2010 U.S. census, only 126 people lived in the town.

“Today one can walk the streets of the old town,” wrote Daniel Metraux in the Southeast Review of Asian Studies. “But most of the buildings standing in the blazing sun are empty save for the ghosts of the original miners who gave life to the town.”

[image error]

Busts of Chinese philosopher Confucius and Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen sit outside a community building in Locke, Calif./Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project.

Chinese immigrants built the town of Locke, California, in 1915 after a fire destroyed a nearby Chinese community. California’s Alien Land Law of 1913 prohibited noncitizens from owning land. So the immigrants secured a lease from George Locke under which they could own any buildings they constructed but not the land itself, which remained in Locke’s possession.

Located near the Sacramento River, Locke served the area’s agricultural workforce, mainly Chinese laborers in the asparagus fields. In addition to homes, it had a small Chinese school, restaurants, a post office, hotels and rooming houses, a theater, grocery stores, a hardware and herb store, a fish market, two dry goods stores, a dentist’s office, a shoe repair, a bakery and a community vegetable garden. Early on, it was also known for its bars, gambling houses and opium dens, which drew hundreds of visitors on weekends.

Locke was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990, and many of the original buildings have been preserved. Today, however, the town has fewer than 100 residents.

More than a century before Carol Highsmith documented Chinese Camp and Locke, photographer Arnold Genthe shot some of the best-known photos of San Francisco’s Chinatown before the earthquake and fires of 1906.

[image error]

Men and children in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Photo by Arnold Genthe.

[image error]

Arnold Genthe with his camera in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

He reported waiting patiently on street corners for hours to capture just the right images to document daily life. Yet Genthe is known to have edited his photographs in the darkroom, sometimes removing signs in English and cropping out westerners like himself. It is not known exactly why he did this—perhaps to make his pictures seem more authentic. But according to modern scholars, he achieved the opposite result: his photographs are now seen by many to convey an exoticized perspective on Chinatown.

Genthe moved to New York City in 1911, where he focused mostly on portraiture, photographing famous figures such as President Woodrow Wilson, actress Greta Garbo, dancer Isadora Duncan and others. The Library acquired 20,000 of Genthe’s photographs after he died in 1942. About 16,000 are available online, including hundreds of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

May 5, 2017

Pic of the Week: Disco Fashion

Fashion expert Tim Gunn (right) discusses disco styles with Deputy Librarian of Congress Robert Newlen. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Platform shoes, bell bottoms and halter dresses were the topic at hand at a May 2 event featuring Tim Gunn, one of America’s leading fashion experts. He spoke about disco styles and what they say about the disco era.

“It was a time of flamboyance. . . . Everyone wanted to stand out,” Gunn said in an interview with Deputy Librarian of Congress Robert Newlen in the Coolidge Auditorium. “It was really a giant runway of sorts,” Gunn explained of the disco dance floor.

The event took place as part of a series of disco-themed events titled “Bibliodiscotheque” that the Library is presenting to celebrate and memorialize the period between the mid-1970s and the early 1980s that changed American art, fashion, language and sound.

View a video recording of the Tim Gunn interview here.

Journalism, Behind Barbed Wire

The following is a guest post by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress Gazette, about a collection of newspapers published by Japanese-Americans held in U.S. internment camps during World War II. The Library placed the newspapers online today.

[image error]

Roy Takeno, editor of the Manzanar Free Press, reads the newspaper at the internment camp in Manzanar, Calif. Ansel Adams Collection /Prints and Photographs Division.

For these journalists, the assignment was like no other: Create newspapers to tell the story of their own families being forced from their homes, to chronicle the hardships and heartaches of life behind barbed wire for Japanese-Americans held in World War II internment camps.

“These are not normal times nor is this an ordinary community,” the editors of the Heart Mountain Sentinel wrote in their first issue. “There is confusion, doubt and fear mingled together with hope and courage as this community goes about the task of rebuilding many dear things that were crumbled as if by a giant hand.”

Today, the Library of Congress places online a rare collection of newspapers that, like the Sentinel, were produced by Japanese-Americans interned at U.S. government camps during the war. The collection includes more than 4,600 English- and Japanese-language issues published in 13 camps and later microfilmed by the Library.

[image error]

Manzanar Free Press, Dec. 22, 1943

[image error]

Topaz Times, Feb. 6, 1943

“What we have the power to do is bring these more to the public,” said Malea Walker, a librarian in the Serial and Government Publications Division who contributed to the project. “I think that’s important, to bring it into the public eye to see, especially on the 75th anniversary. … Seeing the people in the Japanese internment camps as people is an important story.”

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that allowed the forcible removal of nearly 120,000 U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent from their homes to government-run assembly and relocation camps across the West—desolate places such as Manzanar in the shadow of the Sierras, Poston in the Arizona desert, Granada on the eastern Colorado plains.

There, housed in temporary barracks and surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, the residents built wartime communities, organizing governing bodies, farms, schools, libraries.

They founded newspapers, too—publications that relayed official announcements, editorialized about important issues, reported camp news, followed the exploits of Japanese-Americans in the U.S. military and recorded the daily activities of residents for whom, even in confinement, life still went on.

In the camps, residents lived and died, worked and played, got married and had children. One couple got married at the Tanforan assembly center in California, then shipped out to the Topaz camp in Utah the next day. Their first home as a married couple, the Topaz Times noted, was a barracks behind barbed wire in the western Utah desert.

Mimeographs and Printing Presses

The internees created their publications from scratch, right down to the names. The Tule Lake camp dubbed its paper the Tulean Dispatch—a compromise between The Tulean and The Dusty Dispatch, two entries in its name-the-newspaper contest. (The winners got a box of chocolates.)

[image error]

Minidoka Irrigator, Jan. 15, 1944

Most of the newspapers were simply mimeographed or sometimes handwritten, but a few were formatted and printed like big-city dailies. The Sentinel was printed by the town newspaper in nearby Cody, Wyoming, and eventually grew a circulation of 6,000.

Many of the internees who edited and wrote for the camp newspapers had worked as journalists before the war. They knew this job wouldn’t be easy, requiring a delicate balance of covering news, keeping spirits up and getting along with the administration.

The papers, though not explicitly censored, sometimes hesitated to cover controversial issues, such as strikes at Heart Mountain or Poston.

Instead, many adopted editorial policies that would serve as “a strong constructive force in the community,” as a Poston Chronicle journalist later noted in an oral history. They mostly cooperated with the administration, stopped rumors and played up stories that would strengthen morale.

Demonstrating loyalty to the U.S. was a frequent theme. The Sentinel mailed a copy of its first issue to Roosevelt in the hope, the editors wrote, that he would “find in its pages the loyalty and progress here at Heart Mountain.” A Topaz Times editorial objected to segregated Army units but nevertheless urged Japanese-American citizens to serve “to prove that the great majority of the group they represent are loyal.”

“Our paper was always coming out with editorials supporting loyalty toward this country,” the Poston journalist said. “This rubbed some … the wrong way and every once in a while a delegation would come around to protest.”

Like Small-Town Papers

The newspapers maintained a small-town feel, reading like a paper from anywhere in rural America. They announced new library additions, promoted job opportunities, covered baseball games between residents, posted church schedules and advertised shows (“‘Madame Butterfly’ will be presented by Nobuio Kitagaki and his puppeteers”).

They often reflected a grin-and-bear-it humor about their plight. The Tanforan center was built on the site of a horse track, and some residents were quartered in horse stalls that once housed champion thoroughbred Seabiscuit—the source of frequent jokes in the camp newspaper, the Tanforan Totalizer.

A column of whimsical items was named “Out of the Horse’s Mouth.” A story headlined “Home Sweet Stall” reported on progress in living conditions: “Though still far from an earthly paradise, Tanforan has come a long way since the first week when residents were whinnying to one another, ‘Is it my imagination, or is my face really getting longer?’”

As the war neared its end in 1945, the camps prepared for closure. Residents departed, populations shrank, schools shuttered, community organizations dissolved and newspapers signed off with “–30–,” used by journalists to mark a story’s end.

That Oct. 23, the Poston Chronicle published its final issue, reflecting on the history it had both recorded and made.

“For many weeks, the story of Poston has unfolded in the pages of the Chronicle,” the editors wrote. “It is the story of people who have made the best of a tragic situation; the story of their frustrations, their anxieties, their heartaches—and their pleasures, for the story has its lighter moments. Now Poston is finished; the story is ended.

“And we should be glad that this is so, for the story has a happy ending. The time of anxiety and of waiting is over. Life begins again.”

[image error]

Heart Mountain Sentinel, July 28, 1945

The collection is available here.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers