Library of Congress's Blog, page 114

April 7, 2017

Pic of the Week: Echoes of the Great War

A member of the U.S. Army Band tours ”Echoes of the Great War.” Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Library of Congress opened a major new exhibition, “Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I,” on April 4.

The exhibition examines the upheaval of world war as Americans confronted it both at home and abroad. It considers the debates and struggles that surrounded U.S. engagement; explores U.S. military and home-front mobilization and the immensity of industrialized warfare; and touches on the war’s effects as an international peace settlement was negotiated, national borders were redrawn, and soldiers returned to reintegrate into American society.

The exhibition will be on view in the Southwest Gallery of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building through January 2019. To view the related online exhibition, click here.

Inquiring Minds: Delving into the Library’s Jazz Collections

Larry Appelbaum, left, with Ingrid Monson in the Whittall Pavilion on March 1. Photo by Michael Turpin.

Ingrid Monson is the Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music at Harvard University and an award-winning author and scholar whose work in jazz, African American music and the music of the African diaspora is greatly respected. Her books include “Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa” and “Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction.”

Monson spent two weeks in March in residence at the Library of Congress conducting research in the Music Division’s jazz collections. She did so under the auspices of the Jazz Scholar Program, a collaborative effort of the Library and the Reva and David Logan Foundation.

On March 1, Monson sat down with Larry Appelbaum, the Music Division’s jazz specialist, in the Whittall Pavilion to discuss her research in the Max Roach Collection.

Jazz drummer and composer Roach (1924–2007) was a pioneer of the modernist style known as bebop and a highly regarded creator of innovative jazz, whose collection the Library acquired in 2013. It includes his personal papers, musical scores, audiovisual recordings and related materials.

The following is an excerpt from the interview between Appelbaum and Monson.

Monson: I was delighted to be invited to come to the Library of Congress and be here for two weeks in residence. I’ve wanted to come and work on the Max Roach Papers for quite some time, and you just made it easy. . . .

[image error]

Max Roach at the Three Deuces Club in New York in October 1947. From the William P. Gottlieb Collection.

Appelbaum: I know you wanted to look at Max Roach. Is there something in particular you are hoping to find, and what are you discovering so far?

Monson: Well, I’m very interested in this collection, partly because I wrote a great deal about Max Roach in “Freedom Sounds.” I interviewed him for it, I interviewed Abbey Lincoln [jazz vocalist, actress and wife of Roach from 1962 to 1970] and a number of related people. I went through the documents that were available to me then. But his archive was not available then. So one of the key things I want to look at is what’s in the archive that can enrich the story I’ve already told or correct the story I’ve already told.

So the first box I got out on Monday were the scores to the “Freedom Now Suite” [a 1960 album Roach co-authored with Oscar Brown, Jr., known formally as “We Insist! Freedom Now”]. The care with which these scores are put together is really interesting. Every part of the suite has a score. They’re very detailed, including drum parts . . . for “Triptych,” which is the middle movement.

And then I learned that there was originally an overture written for it that I’ve never heard—it’s there in the box—and that there were some other songs that were being considered between he and Oscar Brown. There are some scores for that material as well. Already I have an expanded sense of . . . their process of trying things out.

There’s also a lot of correspondence that relates to . . . something else that I wrote about in my book “Freedom Sounds,” which was about [jazz critic] Ira Gitler’s review of Abbey Lincoln’s “Straight Ahead” in 1961, which, just, shall we say . . .

Appelbaum: Stirred controversy.

[Lincoln wrote lyrics about race relations for several of the album’s songs, for which Gitler harshly condemned her in racial terms.]

Monson: Stirred controversy is to put it lightly. There was this huge debate about racial prejudice in jazz in early 1962 in [jazz magazine] “Down Beat.” . . . What I found in the correspondence just in the last couple of days is that at the time that Ira Gitler’s review came out, which would have been some time in November of 1961, they [Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln] contacted a lawyer. . . . So the availability of materials like this just enriches what you’re able to see and what you’re able to know about this amazing career that Max Roach had. . . .

Appelbaum: So when you initially interviewed Max about [the “Freedom Now Suite”], what was his take all these years later?

Monson: He was very proud of it. [Monson explains that Roach did not provide extensive details when she interviewed him because he was working on an autobiography at the time with poet and playwright Amiri Baraka. The autobiography was never completed.] . . . But here in the archive are the interviews that they did around 1995 and some drafts that they were working on. That’s another thing I’m taking a look at here. . . .

Appelbaum: If Max were here with us today, what would you like to ask him, these years later?

Monson: One of the things that’s overwhelmed me the last couple of days is I’ve gone through a number of his business papers. And it’s very clear to me that he was deeply involved in the running of his own affairs; [he] had very clear conceptions of his works. In the archive are these yellow notepads where he’s written these elaborate letters in longhand in pencil. Before they’re sent, he’s given them to somebody to type up, so then there’s a typed version of it, too. But he goes back and corrects things. He was right on top of the details of how he was going to be represented in pamphlets and things publicizing his appearances. [He was] very involved in fine-tuning contractual issues. And I think he worked very hard to get paid what he thought he was worth. It’s clear that he was a tough negotiator with these things.

There are also drafts in there of plays that I think he wrote or . . . multimedia kinds of projects in which he very carefully sketches out the drafts, writes a rationale for . . . what his over-arching artistic goals are. So you see an artist at work, and you realize that one thing that an artist like him does is has a vision and works extremely hard to make it happen. So there he is, the logistics of all the instruments that need to be hired, the scoring, the staging, the lighting. I would simply want to ask him more about this and how he moved from the administrative side of his career to the creative side and back. . . .

Appelbaum: We’ve been talking about Roach because that’s been your focus so far. Are there other collections you are particularly interested in, and what do you hope to find in those collections?

Monson: Well, thanks to you, you’ve been showing me these gems from all sorts of collections. I feel like I could stay here for six months. There are so many wonderful things. . . . I’m very interested in the economic picture. There’s a lot of talk about unfair record deals. . . . It’s very difficult to get hard economic information—except from musicians who kept their contracts. . . . You can find out what people got paid, what the terms of their contracts were. So you have a better idea of the economic picture for musicians at the time. I’m very excited at looking at those materials. I’m interested in copyright issues also, so I want to make a trip to the Copyright [Office].

On March 9, Monson gave a public lecture at the Library of Congress discussing her research in the Music Division’s collections.

April 6, 2017

World War I: Library Opens Major New Exhibit, ‘Echoes of the Great War’

The following is a guest post by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress Gazette.

As a surgeon with the U.S. 6th Marines in France, Joel T. Boone saw the cost of World War I up close—comrades mutilated, amputations performed by candlelight, the frightful loss of life.

“My heart has bled by the things I have seen,” wrote Boone, who earned the Medal of Honor for heroism under fire in 1918. “Last night was a perfect inferno. We worked incessantly from 7 until that hour this morning and all day. . . . Officers with both legs gone in the prime of youth is one of the most horrible to see.”

The war was like none before it—a global conflict, waged across continents by dozens of nations, fought with revolutionary weapons, causing tens of millions of casualties.

To mark the centennial of U.S. entry into the war, the Library of Congress on April 4 opened a major new exhibition, “Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I.” “Echoes” examines the upheaval of world war as Americans like Boone lived it, in the trenches and at home.

[image error]

The American Expeditionary Forces ID card of surgeon Joel T. Boone.

“There’s not one American experience of World War I,” said Sahr Conway-Lanz, a historian in the Library’s Manuscript Division. “There are many ways in which Americans experienced the war—what it meant to them, what they went through, how deeply it touched them.”

The war reshaped American society and culture: The U.S. conscripted a national army for the first time; women entered the workforce en masse; African-Americans challenged racial inequality; new technology came into widespread use; American soldiers helped spread jazz around the world.

The Library holds the most comprehensive collection of materials on U.S. involvement in the war. Over the course of its run, “Echoes” will feature more than 600 collection items: music, diaries, correspondence, recorded sound, posters, photos, medals, scrapbooks and maps.

The Library also digitized nearly 26,000 feet of rare film for the exhibition—President Woodrow Wilson picks numbers for conscription, an animation pioneer depicts the sinking of the Lusitania.

“Nitrate stock is very fragile in addition to being volatile; thus, much of this footage has not been seen since the war itself,” said Cheryl Regan, a senior exhibition director in the Interpretive Programs Office. “These silent clips document the American experience in the First World War, on the home front and the front lines.”

Stories from Over There

The exhibition presents documents of great figures—President Wilson’s first draft of the League of Nations covenant, the diaries of American Expeditionary Forces commander Gen. John J. Pershing—and of ordinary men and women, over there and at home.

“One of the great things about this exhibit is that virtually every item tells a story of some kind,” Conway-Lanz said. “It really is amazing what the collections of the Library allow folks to learn about the war.”

The war inflicted more than 38 million military and civilian casualties—about 320,000 of them American. Theodore Roosevelt’s son, Quentin, was one.

[image error]

Soldiers gather by the grave of Lt. Quentin Roosevelt, killed in aerial combat in 1918.

All four of Roosevelt’s sons served in the war (and three would serve again in World War II). Quentin, the youngest, joined the Army Air Service as a pilot and was shot down over France in July 1918—whether killed or captured, Roosevelt didn’t know.

Roosevelt soon received a letter—part of the exhibition—from English author Rudyard Kipling, expressing hope that Quentin was safe. Kipling understood how Roosevelt might feel: His own son was killed in action in 1915.

“The boy has done his work honourably and cleanly and you have your right to pride and thankfulness. . . . No words are any use but we all send you our love and deep sympathy,” Kipling wrote.

Quentin, however, wasn’t safe: He’d been killed in a dogfight, and the Germans buried him where he fell.

Across Racial Lines

Charles Hamilton Houston attended training camp for African-American officers, went to artillery school and shipped out to France. Houston recorded his experiences in a diary—the racial hostility he encountered in the military, the freedom of his postwar service in Paris.

[image error]

Charles Hamilton Houston (second row, fifth from right) poses with African-American officers at a training camp in Iowa.

“Had a good time dancing,” Houston wrote. “French girls anxious to learn our dance; told me that all Paris is taken away with ‘jazz-band’ and our style of dancing. The girls came after the boys in taxis and beg them to go to the dance. Colored boys are all the go.”

Inspired by his military experiences, Houston attended law school, served as dean of Howard University law school, trained a cadre of civil-rights lawyers (including Thurgood Marshall), and, as the NAACP’s litigation director, argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court— work that eventually earned him the nickname “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow.”

“He died in 1950, so he never gets to see the culmination of his efforts,” said Ryan Reft, a historian in the Manuscript Division. “But he lays this groundwork, and World War I is kind of the crucible through which he passes to come to this civil-rights awakening.”

Peace for Patton

George S. Patton earned a reputation as a brilliant commander in the Second World War—one of military history’s most complex and compelling figures.

His first battle experience, however, came in the Great War. Patton led U.S. tanks into battle at St. Mihiel, but a serious wound cut his campaign short on the first day of the war-ending Meuse-Argonne offensive.

[image error]

“Peace” by George Patton.

[image error]The Library holds the Patton papers—including his voluminous war poetry. Patton, fueled by ambition and a sense of his own as yet unfulfilled destiny, wasn’t thrilled when peace finally came.

On the day the armistice was signed, Patton wrote a poem called “Peace,” lamenting the end of hostilities: “I stood in the flag decked cheering crowd / Where all but I were gay / And gazing on their extecy / My heart shrank in dismay.”

Most, however, were glad the “war to end all wars” was over and to return home, to a world that never would be the same.

“The war,” Reft said, “reshaped the world politically, economically and geographically, while setting into motion processes domestically that, for good and for ill, culminated over the next three decades—particularly with America’s participation in World War II.”

The exhibition, located in the Jefferson Building’s Southwest Gallery, closes in January 2019.

April 5, 2017

World War I: A New World Order – Woodrow Wilson’s First Draft of the League of Nations Covenant

(The following was written by Sahr Conway-Lanz, historian in the Library’s Manuscript Division.)

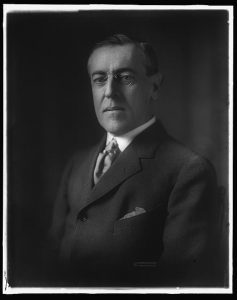

Woodrow Wilson. Between 1900 and 1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

Like many individuals around the globe, Woodrow Wilson was shocked by the outbreak of a devastating world war among European empires in 1914. As President of the United States, however, he had a unique opportunity to shape the outcome of this catastrophic conflict. He was a leading advocate for a new approach to international relations and the problem of war in which the first global political organization, the League of Nations, was to be the key mechanism for ensuring a peaceful and orderly world. Among the papers of Woodrow Wilson maintained by the Library of Congress’ Manuscript Division, one can find Wilson’s first draft of the covenant of the League of Nations, the founding document of the international organization that tried but failed to tame interstate warfare.

President Wilson viewed World War I as the folly of an old style of failed diplomacy. This timeworn diplomacy had sought to balance the power of the great European states and alliances against each other while they competed for selfish imperial interests. Unable to avoid American entry into the war in April 1917, Wilson committed himself to creating a new international order with a League of Nations at its center that would peacefully manage conflicts between states, great and small and put an end to senseless warfare. The League of Nations was not his vision alone – ideas about a society or league of nations to facilitate or even enforce the peace had been discussed among Americans, Europeans and others. Nevertheless, Wilson became a driving force to establish the league as the guarantor of the post-war peace.

President Woodrow Wilson’s first written draft of the League of Nations covenant, the founding document of the new and ill-fated international organization created by the peace settlement at the conclusion of World War I. Manuscript Division.

Written in the summer of 1918, this first attempt by Wilson to define the league laid out his thinking on the new world order he sought to foster. The covenant draft set as the league’s goals to ensure the political independence and territorial integrity of member states, reduce armaments and resolve interstate disputes through arbitration and mediation. To enforce these goals, the document stipulated collection action by member states to blockade, impose trade boycotts and use military means to punish transgressors. Wilson based his version on an earlier draft by his close foreign policy advisor Edward House and marked with an “H” sections of the document from House. Corrections to Wilson’s typed draft in his own hand reveal aspects of the president’s thought process as he labored on this far-reaching project.

The League of Nations is today commonly viewed as a failure. The United States never even became a member of the organization that President Wilson had worked so hard to create. The Library’s Nation’s Forum collection of recordings features a selection of audio clips from American leaders both for and against the League of Nations. In addition, the Library’s historical newspaper collections document the evolution of the covenant.

However, the league was the first international organization that was global in scope, representing an extraordinarily hopeful vision of a peaceful global community, and was an important predecessor to the United Nations and current internationally shared ideas of collective security and limits on war.

The Woodrow Wilson papers at the Library of Congress are the most extensive and significant collection of Wilson documentation found anywhere and include his White House files as well as personal and professional materials from the rest of his life.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

April 4, 2017

Champions of America: Early Baseball Card

This 1865 portrait of the Brooklyn Atlantics is considered an early prototype for baseball cards.

Baseball “has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere—belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly, as our constitutions [and] laws.

—Walt Whitman

What better way to welcome April—National Poetry Month and the start of baseball season—than with a quotation about baseball from one of America’s greatest poets?

Americans have debated the exact origins of their national pastime for more than a century. But it’s generally agreed that the American game of baseball started in towns and cities of New England, New York and the Mid-Atlantic, with rules of play varying by region. The Knickerbocker Club, formed in New York in 1845, was among the first organized baseball clubs. It instituted the so-called New York rules, considered to be the basis for the modern game. On June 19, 1846, the Knickerbockers played under the rules for the first time at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey. The local press championed the sport, including Walt Whitman, who as an editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1846, proclaimed, “The game of baseball is glorious.” An avid player himself, Whitman associated baseball with vigor, masculinity and health.

The Civil War boosted the popularity of the game, which was often played by soldiers in camp. After the war, they took it home with them, and it spread to every region of the country. As baseball increasingly captured the American imagination, baseball-inspired visual works proliferated, a trend continued to this day.

“Champions of America” is a portrait of the Brooklyn Atlantics. Mounted on a card, the photo was passed out as a souvenir to fans and is considered an early prototype for baseball cards, which first became popular in the 1880s. The Brooklyn Atlantics won championships in 1861, 1864 and 1865. Their season continued throughout the winter, when the team donned skates and played on frozen ponds.

The type at the bottom of the photograph indicates that photographer Charles Williamson registered the copyright to the photo in 1865 in U.S. district court for the Eastern District of New York.

The Library of Congress has a collection of more than 2,000 early baseball cards from 1887 to 1914. They portray such legendary figures as Ty Cobb stealing third base for Detroit, Tris Speaker batting for Boston and Cy Young posing in his Cleveland uniform.

Happy Spring!

“Spring” by Penrhyn Stanlaws

Temperatures are still a little cool here on the East Coast, but it’s definitely time to put those winter coats away: spring arrived officially on March 20 at 6:29 am EDT. Soon, pleasant days like the one captured in this poster will be common. Penrhyn Stanlaws created the poster in 1907 and titled it, simply, “Spring.”

It is part of the Library’s online Artist Poster Collection. Online offerings make up a small but growing proportion of the more than 85,000 artist posters in the Library’s collections, dating from the 19th century to today. The series includes many fine examples from styles including Art Nouveau, Russian Constructivism, Art Deco, Bauhaus and Psychedelic.

Most of the posters were produced in the United States, but other countries are represented as well. The posters came to the Library as copyright deposits, gifts, transfers, purchases and exchanges; their subject matter covers travel and tourism, cultural events, advertising, sports and more.

Penrhyn Stanlaws (1877–1957) was a well-known portrait painter and illustrator of his day. His depictions of elegant “Stanlaws Girls” graced the covers of magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Colliers, and their popularity rivaled that of Charles Dana Gibson’s “Gibson Girls.”

Born in Dundee, Scotland, the multitalented Stanlaws built the Hotel des Artistes in New York City in 1917, then the largest studio building in the United States, and he directed motion pictures including “The Little Minister” starring Betty Compson. He died in Los Angeles after falling asleep while smoking in an upholstered chair, setting his studio on fire.

April 3, 2017

Play Ball!

This is a guest post by Jeffrey Flannery, head of the Reference and Reader Services Section of the Manuscript Division.

[image error]

Branch Rickey

Spring has arrived, which all fans know marks the beginning of the baseball season. Opening day was April 2 for major league baseball, and the new season brings hope that this year may be the year for the hometown nine. The traditions of baseball form an important part of the appeal of this unique sport, with the rich history of the game, filled with innumerable stories and statistics, keeping fans interested all year long.

No one encapsulates baseball’s history more than Branch Rickey (1881–1965), a former player and manager who became an innovative baseball executive and part owner.

In a career spanning nearly 60 years, Rickey is perhaps best known as the man responsible for bringing Jackie Robinson into major league baseball in 1947, thereby breaking baseball’s long-established color barrier. The Library of Congress Manuscript Division’s collection of Branch Rickey Papers offers a fascinating glimpse into the history of 20th-century baseball, viewed through the prism of this influential figure.

The Rickey Papers are extensive, including 29,000 items of correspondence, photographs, memoranda, speeches, scrapbooks, subject files and notes, arranged in 87 containers, as described in the collection’s finding aid and available for research use in the Manuscript Reading Room.

[image error]

Rickey’s frank assessment of Henry (Hank) Aaron, 1963

Perhaps the most intriguing part of the trove documenting Rickey’s extraordinary career are the scouting reports he compiled during the 1950s and 1960s. Long active as a player evaluator, by 1963 Rickey was in the sunset of his career and serving as a consultant for the St. Louis Cardinals. But the reports of this period still show him as an astute judge of talent and also reveal his unique appraisal style.

Rickey evaluated all players who crossed his path with an unsparing eye, be they rookie or veteran, and his reports are written in a strongly opinionated, succinct and often caustic style. Some reports resemble modern-day tweets in their brevity and make for provocative reading.

For example, he says of Henry Aaron, the greatest home-run hitter of the 20th century, “[I]n spite of his hitting record and admitted power ability, one cannot help think that Aaron is frequently a guess hitter.” Of Willie Mays, another Hall of Famer, Rickey wrote, “I would pitch a lot of slow stuff to Mays, particularly when he is anxious to hit. The slow curve ball he ‘slobbers’ all over the place.”

[image error]

Rickey’s dismissal of Minnie Minoso, 1963

Of course, not every player Rickey evaluated was Hall of Fame material. Roy Majtyka was a minor league infielder for the Cardinals who later coached briefly in the major leagues before settling in as a minor league manager. He caught Rickey’s attention but was dismissed as “a puny hitter. Pretty good runner, pretty good fielder. A nice boy.”

[image error]

Report expressing Rickey’s interest in Don Drysdale, 1954

Some of Rickey’s reports are written in a jargon that requires knowledge of references beyond baseball. In April 1963, Rickey produced a report on aging Cuban star, Orestes “Minnie” Minoso, then with the Cardinals. After reluctantly admitting that the player would have to be traded before the season began, Rickey wrote, “[O]f all the old ‘spavs’ who are not calculated, in my opinion, to win a pennant for St. Louis, Minoso comes the nearest qualifying for retention. Good-bye Minoso.” A “spav” is a truncated reference to spavine, an arthritic condition found in racehorses.

Of course, Rickey did not always get his man. In 1954, then with the Pirates, Rickey scouted and sought to sign a young Don Drysdale, but Rickey’s old team, the Dodgers, beat him to it. In an annotation, Rickey noted “signed with Brooklyn, father is bird dog for them.” A “bird dog” was an unpaid scout.

Rickey’s career had a significant impact on baseball. Enshrined in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, Rickey’s contributions are a legacy to the game that endures to this day.

[image error]

Brief remarks about Majtyka, 1962

March 31, 2017

Pic of the Week: Celebrating Cherry Blossoms

A cherry tree in full bloom this week on the grounds of the Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, looking toward the Adams Building. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C., reached peak bloom this week, just in time for the National Cherry Blossom Festival. This year’s festival commemorates the 105th anniversary of the gift of some 3,000 cherry trees to Washington, D.C., from the city of Tokyo in 1912. The trees were given as a symbol of friendship between the United States and Japan. Only nine trees from the original gift remain, two of them located on the grounds of the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress.

A webcast illuminating the history of Washington’s cherry trees, the significance of cherry blossoms in Japan, and their continuing resonance in American culture is available here.

Women’s History Month: First Woman Sworn into Congress 100 Years Ago

Jeannette Rankin, 1917

One hundred years ago this Sunday—on April 2, 1917—Jeannette Rankin was sworn into the 65th Congress as the first woman elected to serve. She took her seat more than two years before Congress passed the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, giving women nationwide the right to vote. That alone is remarkable, but Rankin also made history in another way: she voted against U.S. involvement in both 20th-century world wars—and paid a price for doing so.

To commemorate Rankin’s life and career, the Library of Congress is co-presenting a world premiere song cycle on April 7 with Opera America. “Fierce Grace—Jeannette Rankin,” a collaborative work by multiple women composers, will be performed in the Coolidge Auditorium, followed by a panel discussion.

Rankin campaigned in 1916 as a suffragist, pacifist and social reformer, prevailing against seven men in the Republican primary in her home state of Montana, where women had gained the right to vote in 1914. She became a national celebrity when she won a seat in the general election to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Rankin arrived in Washington, D.C., to festivities in her honor. Suffrage leaders, including Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul, hosted a breakfast for her, and a procession of suffragists accompanied her to the Capitol. Fellow House members greeted her with applause.

[image error]

Jeannette Rankin, right, in a carriage with Carrie Chapman Catt, center, upon Rankin’s arrival in Washington, D.C.

But things turned somber quickly. On the evening of April 2, President Woodrow Wilson called on Congress to authorize U.S. entry into World War I. On April 6, after days of debate, Rankin joined 55 congressional colleagues in voting against the war resolution. She did so in opposition to many suffragists, who feared a no vote would hurt the suffrage cause. “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war,” Rankin is widely quoted as stating.

For the remainder of her term, Rankin advocated for the rights of women and children, worker safety, and equal pay for women, and she played a major role in bringing a suffrage amendment to the House floor, where it passed before the Senate voted it down.

Rankin ran for a Senate seat in 1918, but she failed to win her primary. She returned to private life, moving to Georgia, where she lectured and supported causes dear to her, including women’s rights and peace.

She ran for Congress again in 1939, following the start of World War II in Europe. She felt that she could have the most effect as a member of Congress in keeping the United States out of the war. She returned to Montana to run as a peace candidate, winning handily.

But her time in Congress was once again short lived. She was the only member to vote against U.S. entry into the war on December 8, 1941. “As a woman I cannot go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else,” she reportedly said. An angry mob nearly attacked her when she left the chamber, and she sought safety in a telephone booth, where police rescued her.

At the end of her term, Rankin opted out of national politics for good, although she continued her involvement in peace efforts, speaking out against the Korean and Vietnam Wars. On January 15, 1968, at age 87, she led nearly 5,000 women in a march on Washington, D.C., against the Vietnam War. The marchers called themselves the Jeannette Rankin Brigade. Rankin died in May 1973 at age 93.

In an article published in McCalls’s magazine in 1958, John F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator, cited Rankin as one of three truly courageous women in U.S. history. “Few members of Congress since its founding in 1789 have ever stood more alone, more completely in defiance of popular conviction,” Kennedy wrote. We may disagree with her stand, he added, but it is impossible not to admire her courage.

Information about Library of Congress concerts and ticketing is available here.

March 30, 2017

Women’s History Month: Those Magnificent Women in Their Flying Machines

This is a guest post by Henry Carter, digital conversion specialist in the Serial and Government Publications Division.

In the first decades of the 20th century, aircraft were new, and flying was exciting. Newspapers, the most powerful media outlet of the time, reported broadly on this new technology and its celebrities as well as the many social changes of the early 1900s—including the advent of women pilots, described in one 1910 headline as “heroines of the air.”

[image error]Sissieretta Jones. Read more about it!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers