Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Robinson Crusoe

All Around Dickens Year

>

Robinson Crusoe (end) by Daniel Defoe - Group Read (hosted by Erich)

Summary of (Chapter 20)

Summary of (Chapter 20)

Robinson decided to visit the wreck in order to see if there might be something of use to him there and, more importantly, to find out if there might be any survivors. He stocked his canoe with provisions and prayed for success. He paddled along the shore until he came to the point on the northeast side of the island and paused to reconsider whether he would take the enormous risk of venturing out into the ocean, where the dangerous currents and winds flowed and he might be swept out to sea.

The thought occurred to him that, as the currents reversed at the change of tides, if he timed his attempt correctly he could ride the ebb tide away from the island toward the east, explore the wreck, and then ride the flood tide back to the island. With this in mind, he climbed a hill that allowed him to observe that the current during the ebb tide flowed along the south side of the island, while the current during the flood tide flowed along the north side. If he were to keep to the north on his return, he should be able to ride the current as he had hoped.

The next morning, Robinson set out as he had planned, and within two hours he arrived at the wreck. The ship was of Spanish make and was stuck between two rocks on the point. The stern of the ship was heavily damaged, and the masks had broken off due to the extreme violence of the storm.

As he approached the ship, a dog appeared and leaped into the sea to swim to Robinson’s canoe. He fed and gave water to the animal, which was nearly dead with hunger and thirst.

When he boarded the ship and looked into the cookroom, he saw two drowned sailors embracing each other in death. There was no other sign of life, and most of the goods on the ship were either spoiled by the water or completely inaccessible. He managed to retrieve two seamen’s chests, and he deposited them in his canoe without opening them. Other useful items that he discovered and took included a cask of liquor, some gunpowder, a fire shovel and tongs, some small pots, and a gridiron. Robinson believed that the ship was carrying many valuables along a trade route from the Caribbean to Spain, but as the bow was submerged there was no way for him to access it, and it would have been of no use to him unless he were rescued in the future.

When the tide turned, Robinson returned to the island as he had planned, arriving in the evening extremely tired. He slept in his canoe that night, and in the morning he decided to move the goods to his newest cave.

Opening the seamen’s chests, he found several valuable items, including bottles of medicinal waters, candied fruit, several shirts, linen handkerchiefs, and neckcloths. He also discovered silver and gold coins along with small bars of gold, which were as useful to Robinson as “the Dirt under my Feet; and I would have given it all for three or four pair of English Shoes and Stockings.” Indeed, he did take the shoes from the two dead men he had seen, and he also found two more pairs in one of the chests, but they were pumps and so less useful to him than shoes would have been.

He brought the money back to the cave as well and added it to that he already had.

17th-Century Pumps

17th-Century PumpsPumps were welcome to Robinson but were less practical than standard shoes would have been due to the raised heels. Here is an image of a late 17th-century pair of pumps, perhaps similar to those that he found on the Spanish ship:

To me, the most valuable acquisition from the Spanish ship was a new dog companion!

To me, the most valuable acquisition from the Spanish ship was a new dog companion!We'll complete this chapter tomorrow. Over to you in the meantime!

I enjoyed how Robinson was developing his intuition (in Chapter 18), or listening to the guidance from higher forces.

I enjoyed how Robinson was developing his intuition (in Chapter 18), or listening to the guidance from higher forces. Robinson's fears for his safety replacing most other thoughts is very sad and very familiar :( Erich, I also thought of the good old Maslow's pyramid. The king and lord is pitifully reduced.

Re: Samuel Taylor Coleridge's words. I'm not sure I agree. I think Robinson is extremely resourceful and persevering, probably more so than most people.

'[T]he expectation of evil is more bitter than the suffering <...>'. How true! I feel like I could have written parts of this chapter.

Like Sam, I also thought the ship in the storm might belong to the pirates, what then? I'm so glad he saved the dog, though! But frustrated he doesn't mention the dog in the following paragraphs.

Re: 'the savages'. It has actually occurred to me that Robinson could just try to scare them off by producing an explosion, for instance. He seems not to consider this option.

Robinson about money: '<...> which if I had ever escap'd to England, would have lain here safe enough, till I might have come again and fetch'd it'.

W-what?! So if he ever got away from the island, he would consider going back for the money?! Knowing what happened to his ship and to this other ship?! So much for 'dirt under my feet'.

Love the 17th-century pumps! :) Note the little pot for making chocolate. It was all the rage in Spain for several centuries. My favourite part is when the churchmen said it was not OK to drink chocolate in church, whereas the ladies protested that they needed it to keep up their attention during really long sermons :)

Plateresca: "It has actually occurred to me that Robinson could just try to scare them off by producing an explosion, for instance. He seems not to consider this option."

Plateresca: "It has actually occurred to me that Robinson could just try to scare them off by producing an explosion, for instance. He seems not to consider this option."He considered creating an explosion earlier, but he felt that it would waste a lot of powder and that also they would return knowing that he was there.

He could also try to steal one of their canoes if it was better made than his, but if he left the island for the mainland, it is more likely he would find cannibals than Europeans.

Plateresca wrote: "Robinson about money: which if I had ever escap'd to England, would have lain here safe enough, till I might have come again and fetch'd it'....

Plateresca wrote: "Robinson about money: which if I had ever escap'd to England, would have lain here safe enough, till I might have come again and fetch'd it'....W-what?! .....! So much for 'dirt under my feet'."

I agree, Plateresca. That was my thought when I read this.

I suppose he'll need money to establish himself, if he's ever rescued, but one woult think he'd bring it along right away and not return to the island.

I'm glad that Robinson could save that poor dog.

I'm glad that Robinson could save that poor dog. I like those 17th century pumps. They are very ornate for everyday wear. If Robinson's pumps are as ornate, he'll look quite posh roaming his island. LOL.

Petra: "I like those 17th century pumps. They are very ornate for everyday wear. If Robinson's pumps are as ornate, he'll look quite posh roaming his island. LOL."

Petra: "I like those 17th century pumps. They are very ornate for everyday wear. If Robinson's pumps are as ornate, he'll look quite posh roaming his island. LOL."As usual, he doesn't give us many details. I like to imagine that's what he is wearing.

Summary of (Chapter 20 cont.)

Summary of (Chapter 20 cont.)

After moving his new acquisitions to his cave, Robinson paddled his canoe back to the place in which he had kept it before and then returned overland to his enclosure. After his recent adventure, he continued to be wary of cannibals and kept mostly to the east side of the island, where they never ventured.

Following his disappointment at not being able to escape the island on the Spanish ship, he thought more often about somehow getting away. The narrator comments that Robinson stands as “a Memento to those who are touched with the general Plague of Mankind, whence, for ought I know, one half of their Miseries flow; I mean, that of not being satisfy’d with the Station wherein God and Nature have place’d them.” He describes his failure to follow his father’s advice as his “Original Sin,” and he figures that, had he remained in Brazil, he would after all this time have become one of the richest planters there. He laments the youthful impatience that led him to leave to “fetch Negroes” when by waiting and paying a slave trader he could have achieved his end.

One night in the twenty-fourth year of his residence on the island, Robinson lay in bed awake and reflecting on his past. He recalled that his first years on the island were the happiest since he was unaware that he was in danger from cannibals, and he marvelled at the way in which God tends to limit mankind’s “Sight and Knowledge” of the dangers that surround him so that he may be able to live a serene life. At the same time, he was thankful for the unseen protection he had received from “falling into the Hands of Cannibals, and Savages, who would have seiz’d on me with the same View, as I did of a Goat, or a Turtle.”

Robinson pondered why it was that God had allowed “any of his Creatures [...] to devour its own Kind.” He thought about where the cannibals came from and whether he might be able to go there as a means of escaping the island. However, he was so fixated on the idea of escape that he failed to consider what would happen were he to be captured by the cannibals or, if he avoided that, how he could possibly survive without the provisions and shelter that he had developed on the island. He imagined himself somehow meeting up with “some Christian ship” or arriving at an inhabited country where he could find relief.

After a couple of hours of these speculations, he fell into a deep sleep and began to dream. In his dream, he saw a “Savage” escape from eleven others who had brought him to the island as a captive and victim. When the man encountered Robinson and begged him for help, he brought him to his hidden enclosure. He imagined that the man could serve as a “Pilot” who could guide him to safety. When he awoke, Robinson was at first filled with joy, but when he realized that it had only been a dream, he was incredibly disappointed.

His dream, though, had convinced Robinson that the best way for him to escape from the island would be for him to “get a Savage into my Possession,” especially one that he had rescued and that would owe him a debt. However, to do so, he would need to kill the captors in order to rescue the victim. Previously, he had argued that he should leave it to God to punish the cannibals if he thought fit; now, he concluded that “shedding so much Blood” would be justified since it would be the means of his escape and, moreover, that “those Men were Enemies to my Life.”

Having overcome his scruples about killing the men in order to rescue a captive, the next question was how to bring it about. Robinson decided to seek out his opportunity, and he began to visit the more frequented parts of the island regularly in hopes of seeing their canoes. His musings became more elaborate, and he “fancied my self able to manage One, nay, Two or Three Savages, if I had them, so as to make them entirely Slaves to me, to do whatever I should direct them, and to prevent their being able at any time to do me any Hurt.”

Illustrations for Chapters 19-20

Illustrations for Chapters 19-20

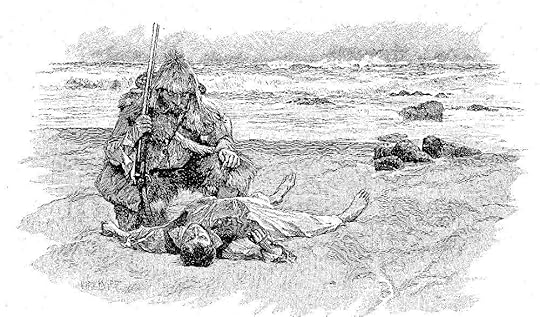

Crusoe finds a drowned boy

Edward Henry Wehnert, 1862

The corpse of a drowned boy

Wal Paget, 1891

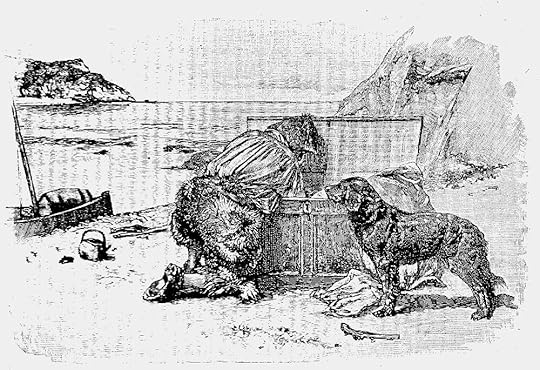

Crusoe Visits the Spanish Ship

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Began to examine the particulars

Wal Paget, 1891

Crusoe sleeping in his Boat

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

We see in this chapter support for Sam's observation about the attributes that Defoe/Crusoe assigns to the natives. It is morally permissible to kill them if it means that he can escape and (he assumes) they would kill him if they had the chance, so they represent an existential threat. Also, it is natural that they would be his slaves, rather than the "relief" that he would expect from fellow Europeans.

We see in this chapter support for Sam's observation about the attributes that Defoe/Crusoe assigns to the natives. It is morally permissible to kill them if it means that he can escape and (he assumes) they would kill him if they had the chance, so they represent an existential threat. Also, it is natural that they would be his slaves, rather than the "relief" that he would expect from fellow Europeans.I'm looking forward to your thoughts!

I understand it was natural for Crusoe to think about enslaving a savage in these terms, but for a modern reader, this is a tough bit to swallow, I'm afraid. So thank you for providing the artwork, Erich :) I especially enjoyed the one with the dog, of course!

I understand it was natural for Crusoe to think about enslaving a savage in these terms, but for a modern reader, this is a tough bit to swallow, I'm afraid. So thank you for providing the artwork, Erich :) I especially enjoyed the one with the dog, of course!

It’s interesting that Defoe includes a dream in the narrative at this point. Is he preparing us for a future event that might have a connection to the dream? It seems like when tv shows use the flashback sequence to inform us of what’s already happened.

It’s interesting that Defoe includes a dream in the narrative at this point. Is he preparing us for a future event that might have a connection to the dream? It seems like when tv shows use the flashback sequence to inform us of what’s already happened. RC was very comfortable on his island prior to finding the footprint and now he mostly thinks about how he can escape. His fear is causing his thought processes to change. His new scheme of taking a savage as a slave to help him is interesting. I’m not sure of the logic just yet. And another thought that I had. RC has not considered being a voice of spreading the knowledge of God to the “savages.” Instead of trying to escape, he could be the one to evangelize these people. I know the fear of cannibalism is a huge deterrent. But still…just a different possibility he hasn’t even thought about. Without the “savages” hearing the morality of the Christian faith, they will never know that there is any other way to live.

Lori: "RC has not considered being a voice of spreading the knowledge of God to the “savages.” Instead of trying to escape, he could be the one to evangelize these people. I know the fear of cannibalism is a huge deterrent. But still…just a different possibility he hasn’t even thought about. Without the “savages” hearing the morality of the Christian faith, they will never know that there is any other way to live."

Lori: "RC has not considered being a voice of spreading the knowledge of God to the “savages.” Instead of trying to escape, he could be the one to evangelize these people. I know the fear of cannibalism is a huge deterrent. But still…just a different possibility he hasn’t even thought about. Without the “savages” hearing the morality of the Christian faith, they will never know that there is any other way to live."To do that, he would first need to make contact, very risky! You're right that it hasn't been part of his thought process so far. He has commented that he can't hold them completely responsible for their cannibalism, but he concludes that, "neither in Principle or in Policy, I ought one way or other to concern my self in this Affair. That my Business was by all possible Means to conceal my self from them."

Calvinist denominations tend to be evangelical, but Defoe has not included evangelical activities at all so far in the text, even among the Europeans. Robinson explains at the beginning of the book that he received a basic education, and in his arguments for the "middle Station" his father reasons based on Christian virtues such as temperance and moderation. Robinson begins to develop his religious sensibilities when he finds Bibles in the shipwreck rather than, say, being converted by a comrade.

Even when he escapes slavery with Xury, Robinson does not try to convert him to Christianity. He forces him to "stroak your Face to be true to me, that is, swear by Mahomet and his Father's Beard."

Defoe has not forgotten the reader with his didactic goals, though!

Summary of (Chapter 21)

Summary of (Chapter 21)

About a year and half after he formed his plot to capture a native, Robinson was surprised one morning to see five canoes beached on his side of the island, but he was unable to see the men themselves. He knew that between four and six men usually rode in a canoe, so he estimated that there were between twenty and thirty cannibals ashore.

He returned to his enclosure, where he waited impatiently, unsure what to do but ready to attack them if he had the opportunity. After some time, he climbed the hill cautiously with his weapons and located the men below. There were indeed about thirty of them, they had lit a fire, and “they had had Meat dress’d.” As Robinson watched, “they were all Dancing in I know not how many barbarous Gestures and Figures, their own Way, round the Fire.”

Robinson saw the cannibals remove two captives from the canoes, and immediately they clubbed and began to cut up one of the prisoners. The other being ignored by the cannibals for the moment, “Nature inspir’d him with Hopes of Life,” and he fled directly toward the part of the island where the enclosure was located.

Robinson remembered the dream he had had, and he imagined that all of the cannibals were in pursuit of the escapee. In fact, though, the man was only being chased by three of the captors, and - being a fast runner - was putting space between himself and them.

When he reached the creek between his pursuers and Robinson’s enclosure, the man swam quickly and skillfully across, followed by two of the three cannibals, who could swim but not as well. It occurred to Robinson that “now was my Time to get me a Servant, and perhaps a Companion, or Assistant; and that I was call’d plainly by Providence to save this poor Creature’s Life.”

As the escapee ran past, Robinson gestured to him to come and then advanced on the other men. He knocked one of them down with a blow to the head with his gun stock, and, seeing the other preparing to shoot him with a bow and arrow, killed him with a single shot.

The escaped captive froze with shock at hearing the gunshot, and then he approached Robinson little by little as Robinson signaled to him. The man was trembling with fear, probably believing that he, too, was about to be killed. As he got closer, he kneeled repeatedly to show his gratitude to Robinson for saving his life, and when he reached Robinson he supplicated himself by lying on the ground and placing Robinson’s foot on his head: “this it seems was in token of swearing to be my Slave for ever.”

The man whom Robinson had felled with a blow began to come to his senses. The escapee spoke some words that Robinson could not understand, but they were pleasant nevertheless as they were “the first sound of a Man’s Voice, that I had heard, my own excepted, for above Twenty Five Years.”

The escaped native was afraid when the injured man managed to sit up. Robinson aimed his gun at the man as if to shoot him, but “my Savage, for so I call him now” instead borrowed Robinson’s sword and cut the man’s head off with a single blow. Laughing, he presented Robinson with both the sword and the severed head.

The escaped captive was amazed that Robinson had been able to kill one of his pursuers from so far away, and he investigated the dead man and explored the wound to try to understand it. Robinson gestured to him that more might be coming and that they should leave, but the other man signaled that he should bury the dead men to hide them from the others.

That being done, Robinson took the man to his cave on the far side of the island rather than to his enclosure. There, he gave him food and water, and after he had eaten the man went to sleep. Robinson found as he observed him that the man was “a comely handsome Fellow” of about twenty-six years old. He had a manly face but also “all the Sweetness and Softness of an European in his Countenance too.”

After he had awoken, he once again supplicated himself to Robinson, showing with his gestures “how he would serve me as long as he liv’d.” Robinson told the man that his name was now Friday because that was the day on which he had saved him. Robinson next taught Friday that his name was Master and to say “yes” and “no.”

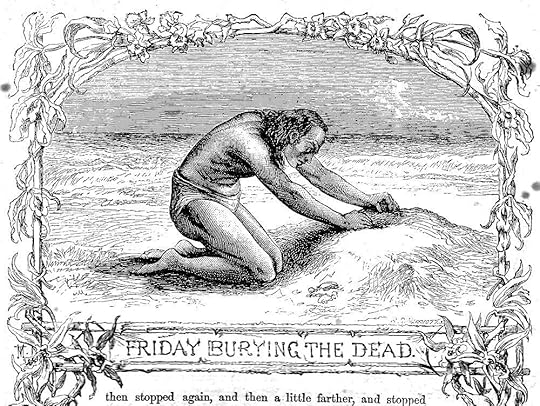

Robinson told Friday that he should have some clothes, “at which he seem’d very glad, for he was stark naked.” On the way to the enclosure, Friday made signs to Robinson that he wanted to dig up the men they had killed in order to eat them. Robinson showed his disgust and forbid it. At the top of the hill, he saw that the other natives had gone and “left their two Comrades behind them, without any search after them.”

Feeling emboldened, Robinson armed Friday and the two of them went to the place on the beach that the cannibals had abandoned. Once again, the “dreadful Sight” of the feast made Robinson’s blood run cold, but it didn’t bother Friday at all. Various body parts and leftovers were scattered about the ground, and Friday signaled that there had originally been four captives, including himself, who had been taken in battle.

Robinson ordered Friday to clean up the site and burn the body parts, but he noticed that Friday “had still a hankering Stomach after some of the Flesh.” Robinson signaled to Friday that it was forbidden and that he would kill Friday unless he left off his cannibalism.

Back at the enclosure, Robinson dressed Friday as well as he could. He next decided that Friday should sleep in a separate tent near the wall of the enclosure. Robinson locked himself in at night so that Friday “could no way come at me” without making noise and alerting him.

The narrator comments that these precautions were not necessary because Friday was a “faithful, loving, sincere Servant” whose “very Affections were ty’d to me, like those of a Child to a Father.” He also marvels at the ways of God, who, even though he places his “Creatures” in such different situations, gives them “the same Reason, the same Affections, the same Sentiments of Kindness and Obligation, the same Passions and Resentments of Wrongs; the same Sense of Gratitude, Sincerity, Fidelity and all the Capacities of doing Good, and receiving Good, that he has given to us.”

Reflecting on these puzzles, Robinson concluded that the ways of God are mysterious, and it is impossible to know why some “have these Powers enlighten’d by the great Lamp of Instruction, the Spirit of God, and by the Knowledge of his Word” and others do not. The only certainty was that God was “infinitely Holy and Just” even though his reasons might be inscrutable to us.

Robinson taught Friday how to do certain tasks to make himself useful, but most of all he tried to teach Friday to understand and communicate with him. He found that Friday was “the aptest Schollar that ever was.”

A couple of days after he had saved Friday, Robinson decided to teach him to appreciate other food than human flesh. When they happened upon a mother goat and her two kids, Robinson shot one of the kids. Hearing the report, Friday thought that he had been shot and began to beg Robinson for his life. Robinson reassured him and indicated that Friday should go and retrieve the dead kid. As Friday was investigating the gunshot wound, Robinson demonstrated how he could kill a bird and make it fall from the sky. Not understanding how the gun functioned, Friday was amazed and assumed that it was a sort of magical death instrument. During the next days, Robinson noticed that Friday sometimes talked to the gun, entreating it not to kill him.

Returning to the enclosure, Robinson dressed the kid and stewed some of the meat to make broth. Although Friday did not like salt on his meat, he enjoyed the meat and broth itself. The next day, Robinson roasted some of the meat, and Friday liked it so much that “at last he told me he would never eat Man’s flesh any more, which I was very glad to hear.”

Illustrations for Chapter 21

Illustrations for Chapter 21Once again, our chapter includes some often-illustrated scenes.

Dancing round the fire

Wal Paget, 1891

Robinson Crusoe first sees and rescues his man Friday

Thomas Stothard, 1782

I was then obliged to shoot

Wal Paget, 1891

Robinson Crusoe rescues Friday

Phiz, 1864

Crusoe and Friday

George Housman Thomas, 1863

At one blow cut off his head

Wal Paget, 1891

Friday burying the Dead

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Crusoe and Friday out Shooting

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Crusoe instructing Friday

Matt Somerville Morgan, 1863

This most recent reading is some of the most exciting and dramatic. It also can seem shocking and distasteful to some of our modern thinking. I find it interesting that a mere fifty years ago, the sense of superiority exercised by Crusoe would not have drawn much attention, and in fact did not become a discussion point in my classes which taught the novel in secondary school or in university.

This most recent reading is some of the most exciting and dramatic. It also can seem shocking and distasteful to some of our modern thinking. I find it interesting that a mere fifty years ago, the sense of superiority exercised by Crusoe would not have drawn much attention, and in fact did not become a discussion point in my classes which taught the novel in secondary school or in university. So I will let the other members comment on this chapter and instead mention thoughts that have been occupying me while reading the novel. When we first started, I was looking to find links between the author and his novels. We can always find similarities between works but Defoe's most popular works, Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and A Journal of the Plague Year do not offer a picture of the author in same way as three works by Dickens, or for that matter, many classic authors. But when I read Defoe, no idea of the author comes to mind, so I was hoping to get a better idea of him, but find I am not getting the answer I sought and am instead coming up with what I think are larger questions.

My biggest question is why are we still reading Crusoe? I don't mean this in a sarcastic or otherwise critical way. I am wondering what is the novel's appeal? It certainly has an appeal. For a piece of literature 300 years old I find this amazing. Beyond Shakespeare, what do we read from the century preceding Crusoe? And his fellow 18th century writers are slipping out of the canon quickly. Fifty years ago, I would have thought Swift would be the dominant author from the period read today, but I hear little of Swift now. Of course not everyone loves Crusoe.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...

But I think there is still an appeal. I will not go into all my thoughts of why, but mostly I think it is because we identify with this character and his philosophy. Individualism and Stoicism are the two leading connections I think. Practicality may be a third. So while we discuss Crusoe and Friday, let us not be too overly focused on the colonialist philosophy, painful as it is. I am not one that feels this novel should be dismissed, instead feeling the novel offers much to learn both about the thinking of the period as well as how we still think today.

Sam, I'd like to finish the book before answering the larger question of whether we should 'let fo of this colonial fairytale', as The Guardian suggests (NB: have all of us read 'RC' before? The article reveals some plot points). But I have a very simple answer as to why I am reading 'RC' now: because we're Dickensians! :) And 'RC' was one of Dickens's favourite novels, it's referenced in many of his books ('MC' included! and we're reading 'MC' next, and maybe that's not coincidental), and, even apart from it being an influential novel for English lit in general... Which brings me to this here my observation:

Sam, I'd like to finish the book before answering the larger question of whether we should 'let fo of this colonial fairytale', as The Guardian suggests (NB: have all of us read 'RC' before? The article reveals some plot points). But I have a very simple answer as to why I am reading 'RC' now: because we're Dickensians! :) And 'RC' was one of Dickens's favourite novels, it's referenced in many of his books ('MC' included! and we're reading 'MC' next, and maybe that's not coincidental), and, even apart from it being an influential novel for English lit in general... Which brings me to this here my observation:When reading about the relationship that's forming between Friday and RC, how many of us have thought of Nicholas Nickleby and poor dear Smike?

(view spoiler)

(Also, Erich is very knowledgeable, and I knew this discussion was my chance to get the most out of this novel).

That said, yes, I do understand what The Guardian is talking about, I do not think RC is a nice gentleman, though, at the same time, what Erich said earlier about reading the text historically is also true: if the attitude we would now define as racism was just the normal attitude white people had at the time, this is it, we can't expect RC to be any different.

Does anybody know where exactly Walter de la Mare wrote his opinion on 'RC'?

Erich wrote: "Calvinist denominations tend to be evangelical [in the sense of "evangelistic"] ...."

Erich wrote: "Calvinist denominations tend to be evangelical [in the sense of "evangelistic"] ...."Most present-day Calvinist denominations do engage in missions and evangelistic work. That development had its main impetus in the evangelistic preaching of Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield (both Calvinists) in the mid-18th-century Great Awakening, and in the pioneering mission work of their fellow Calvinist William Carey, which began late in the same century. But all three of these men faced significant opposition from other Calvinists, which continued to be strong all through the 1800s, and still exists today. Today, Calvinists who object to missions and evangelism are called "hyper-Calvinists," but that term didn't even exist in 1719, when Robinson Crusoe was published.

The distinctive theological tenet of Calvinism is that all those who are eventually saved are eternally predestined to be so by the decree of God, which will guarantee its eventual fulfillment. Most early Calvinists felt that He didn't need any special human help in doing that; they were willing enough to proclaim the Calvinist message in their own homelands, where God had put them, but their general feeling was that if God had wanted to save particular people in Africa or Asia, he probably would have had them be born in a "Christian" country to start with. Human efforts to go to far places to preach the gospel were not high on their to-do lists, and the idea was generally viewed with suspicion. That would have been the sort of Calvinism that Defoe was familiar with.

We also have to realize that in 1719 (and for that matter in the two centuries preceding it, going all the way back to the Reformation), whether they were Calvinists or not, most Protestants were members of state churches, identified with a particular nation-state, and closely tied to its sovereignty. They might evangelize in a colonial context, as a way of "planting the flag," but they simply didn't think of carrying their faith into the world universally, outside of their own nation-state perimeter.

Sam: "My biggest question is why are we still reading Crusoe?"

Sam: "My biggest question is why are we still reading Crusoe?"I like the answer that you give in the following paragraphs, as it is true for me as well. I enjoy the adventure and survival aspects of the novel, and I think that as you and Coleridge point out, it is easy to identify with RC and to put ourselves in his place. I enjoy pondering and discussing the "problems" in the novel with our group, but that is not the main reason that I would set out to re-read it (I am interested, though, in reading Michel Tournier's Friday, or, The Other Island).

Plateresca disagrees with Coleridge's estimation of RC's resourcefulness, but I think that STC is spot-on when he explains why the book has more appeal than Swift. Satire is very topical, and to me it can become tiresome. Adventure, however, is timeless and relatable, especially when the main character has flaws and develops over the course of the story.

My approach to the Imperialism aspects of the work is not to apply my modern morality to them but to acknowledge them and to notice how they serve to frame how the characters interact. The same is true for me with the Christian elements: I'm not reading the story as a spiritual biography, but the text would be very different without the allusions and overt references to Christian ideals.

It hasn't really come up for us, but it is also possible to conduct, for example, a Marxist or feminist analysis of the text. Perhaps that is another reason for its endurance: it contains multitudes.

Plateresca: "When reading about the relationship that's forming between Friday and RC, how many of us have thought of Nicholas Nickleby and poor dear Smike?"

Plateresca: "When reading about the relationship that's forming between Friday and RC, how many of us have thought of Nicholas Nickleby and poor dear Smike?"Interesting! A very different character than Friday, but that scene does seem to echo RC and Friday. There was also the earlier scene between RC and Xury when the latter offers to risk getting eaten by wild beasts to serve RC.

if the attitude we would now define as racism was just the normal attitude white people had at the time, this is it, we can't expect RC to be any different.

I am by no means an expert on literary theory, but I agree that we can't divorce the work of a human writing at a particular time with the historical, social, and cultural forces that surround them. Theories like Formalism and New Criticism tend to disregard the historical or literary context of a work to instead focus on the text as self-contained and structural. When I read Gone With the Wind, for example, I noticed that in her depictions of Mammy, Emmie Slattery, and the KKK, Margaret Mitchell had a clear agenda and made choices based on that. Ignoring that, the book is five stars, but for me it lowers to four stars because those elements become flaws when I consider what was known and understood in 1939.

Werner: "The distinctive theological tenet of Calvinism is that all those who are eventually saved are eternally predestined to be so by the decree of God, which will guarantee its eventual fulfillment. Most early Calvinists felt that He didn't need any special human help in doing that; they were willing enough to proclaim the Calvinist message in their own homelands, where God had put them, but their general feeling was that if God had wanted to save particular people in Africa or Asia, he probably would have had them be born in a "Christian" country to start with. Human efforts to go to far places to preach the gospel were not high on their to-do lists, and the idea was generally viewed with suspicion. That would have been the sort of Calvinism that Defoe was familiar with."

Werner: "The distinctive theological tenet of Calvinism is that all those who are eventually saved are eternally predestined to be so by the decree of God, which will guarantee its eventual fulfillment. Most early Calvinists felt that He didn't need any special human help in doing that; they were willing enough to proclaim the Calvinist message in their own homelands, where God had put them, but their general feeling was that if God had wanted to save particular people in Africa or Asia, he probably would have had them be born in a "Christian" country to start with. Human efforts to go to far places to preach the gospel were not high on their to-do lists, and the idea was generally viewed with suspicion. That would have been the sort of Calvinism that Defoe was familiar with."Thank you for this, Werner! That helps us to understand why Defoe wouldn't include proselytizing as a motive for characters in the text.

As we touched on before, there is a tension between the important concept of predestination and human agency that is similar to the one between determinism and free will. Calvinists solved some of the dilemma by arguing that success and good conduct reflect a person's election, but it was impossible to truly know whether they were chosen. RC believes that he is chosen based on surviving the shipwreck and the various gifts of Providence that he receives. However, he must rely on his own industry and creativity to survive on the island (plus he is protected from danger and guided by an internal voice that is God-sourced). And he can't allow himself to take his election for granted or to relax his vigilance.

Interestingly, John Calvin argued that, although predestination applies to damnation as well as to salvation, the damnation of the damned is caused by their sin while the salvation of the saved is only a result of God's grace. This idea could relate to Robinson's sense of "sinfulness" earlier in the text.

Crusoe's Motive for Rescuing Friday

Crusoe's Motive for Rescuing Fridayfrom Patrick J. Keane in Critical Essays on Daniel Defoe:

What is Crusoe's primary motive in rescuing Friday? Letting the rescued, yet also captured, cannibal know "I was very well pleased with him," Crusoe, as a number of readers have pointed out, echoes the voice of God at the baptism of Jesus. This baptismal symbolism, though critical to the salvation theme of the novel, only partially justifies Paula Backscheider's conclusion that, when Crusoe names Friday, "he is not committing an imperialist act but 'christening' a man given not only his mortal life but hope for eternal life." Crusoe had, to be sure, added to his thoughts about acquiring a "servant" or "perhaps a companion or assistant" the conviction that "I was called plainly by Providence to save this poor creature's life." He soon turns him - an example of Crusoe's prudishness rather than any Defoe parody of the Augustan tradition of rigging out black servants in outlandish costumes - into a decently clothed "Protestant," and, upon reflection, remarks that his own grief was lightened to have been made "an instrument under Providence to save the life, and, for ought I knew, the soul of a poor savage, and bring him to the true knowledge of religion." Reflecting on this, he feels a "secret joy run through every part of my soul, and I frequently rejoyced that ever I was brought to this place, which I had so often thought the most dreadful of all afflictions that could possibly have befallen me."

[...]

In fact, Crusoe's initial motive in rescuing Friday was less religious than political, and more utilitarian than either. In the dream preceding the rescue, Crusoe told himself that any cannibal he might save could serve as a "pilot" to help him escape from the island over which he no longer feels himself to be absolute sovereign. There is, of course, no question as to relative sovereignty. When he awakens, dejected, to find his dream is only that, Crusoe resolves, since this is the "only way" escape seems possible, "to get a savage into my possession." Later, as a "first" step in communication, having let the rescued man "know his name should be Friday, ...I likewise taught him to say Master, and then let him know, that was to be my name."

They are, then, to be master and slave, with Friday treated as Kantian or Coleridgean "means" rather than "end;" continuing to dream of escape, Crusoe thinks, "this poor savage might be a means to help me." They work together, but the most menial tasks fall to the servant; indeed, as "Friday," the new man may be said to initiate Crusoe's sabbath, the biblical day of rest. No amount of subsequent affection, even "love," changes this fundamental relationship, Friday having sworn by abject gesture, as Crusoe twice tells us, "to be my slave for ever." More than one Defoe critic, noting parallels between Robinson Crusoe and The Tempest, has suggested that in their overcoming of adversities on the island, Crusoe and Friday resemble Shakespeare's Prospero and Ariel. True enough, though in terms of cultural and racial resonances, we seem closer to the truth in associating Master Crusoe and Man Friday with Prospero and Caliban - the latter sharing with Friday a principal role in English literature as symbol of the colonized races, and, in a number of cultural reclamations by Caribbean writers, as an "inaugural figure." As a native of the island most intimately affected by British colonial expansion, an expansion foreshadowed for many by the hardy deeds of "staunch Crusoe," James Joyce cast a cold eye on Defoe's hero: "The true symbol of the British conquest is Robinson Crusoe ... He is the true prototype of the British colonist, as Friday (the trusty savage who arrives on an unlucky day) is the symbol of the subject races." Note: on an "unlucky" - not a providential - day. For Crusoe's "new companion," however well treated, remains, unlike Ariel, a permanent slave or servant, a "creature" taught "every thing that was proper to make him useful, handy, and helpful."

We are going to have two break days before we move on to the next section on Saturday. There is plenty of time for catching up and comments!

We are going to have two break days before we move on to the next section on Saturday. There is plenty of time for catching up and comments!

This chapter was full of excitement and kept me grimacing a lot with the introduction of cannibalism. Obviously RC decided that he would kill two savages in order to save one. The rescued savage does not seem to be abhorrent and does let RC know he is grateful to him for his life. Again, they don’t understand one another but the savage seems astute enough to learn RC’s language and acceptance of clothes and of eating meat other than human. He doesn’t present himself as scary yet RC is still suspicious thinking he might kill him in his sleep. I can only imagine how starved for companionship he is after 25 years with no human interaction.

This chapter was full of excitement and kept me grimacing a lot with the introduction of cannibalism. Obviously RC decided that he would kill two savages in order to save one. The rescued savage does not seem to be abhorrent and does let RC know he is grateful to him for his life. Again, they don’t understand one another but the savage seems astute enough to learn RC’s language and acceptance of clothes and of eating meat other than human. He doesn’t present himself as scary yet RC is still suspicious thinking he might kill him in his sleep. I can only imagine how starved for companionship he is after 25 years with no human interaction. There was a bit of humor when the savage would talk to RC’s gun in an attempt to ensure that it would not kill him. And another interesting detail included is that he didn’t like salt.

And thank you to Werner for the further clarification on the evangelistic nature of this time.

Lori: "they don’t understand one another but the savage seems astute enough to learn RC’s language and acceptance of clothes and of eating meat other than human."

Lori: "they don’t understand one another but the savage seems astute enough to learn RC’s language and acceptance of clothes and of eating meat other than human."I wonder if RC will attempt to learn any of Friday's language. He named him without asking him if he had a name already. It's likely that he did.

I was struck by the fact that the novel seems to assume that since a cannibal eats human flesh, that is all they eat. Most cannibalism historically is related to famine or ritual rather than being a regular part of the diet, so I would expect that Friday and the other natives would be very familiar with roasted goat flesh.

Summary of (Chapter 22)

Summary of (Chapter 22)

Robinson put Friday to work doing menial tasks such as sifting grain. In addition, he taught Friday how to complete processes such as making bread. Because there were now two of them to support, Robinson and Friday also enlarged the fields.

What followed was “the pleasantest Year of all the Life I led in this Place” because Robinson was finally able to communicate with another person after such a long time alone. Friday learned to speak English readily and showed himself to be honest and affectionate.

When Friday had learned enough English to communicate clearly, Robinson asked him about his home nation, how he had come to be captured, and how his people ate their captives. Friday revealed that he had visited the island in the past to join one of the feasts, and he explained how the natives used the currents created by what Robinson later learned was the Oroonooko River to travel back and forth from the mainland. During their conversation, Friday indicated that there were Europeans, likely Spanish, in a country to the west. When Robinson asked if it would be possible for him to leave the island and go there, Friday said that it was but that it required a larger boat.

Along with teaching Friday tasks and language, Robinson endeavored to “lay a Foundation of Religious Knowledge in his Mind.” When he asked Friday about his beliefs, Friday explained that the world had been created by “one old Benamuckee, that liv’d beyond all.” Benamuckee was older than the world, all worshipped him, and people who died went to join him.

By drawing analogies from Friday’s native beliefs, Robinson “began to instruct him in the Knowledge of the true God.” Gradually, Friday accepted the omnipotence of Robinson’s God and the ability of followers of Jesus Christ to pray directly to God. The power of the Christian God to hear prayers from so far away convinced Friday that he was much more powerful than Benamuckee, who could only receive the people’s prayers through the intercession of a priest. The narrator comments that “there is Priestcraft, even amongst the most blinded ignorant Pagans in the World, and the Policy of making a secret Religion, in order to preserve the Veneration of the People to the Clergy, is not only to be found in the Roman, but perhaps among all Religions in the World, even among the most brutish and barbarous Savages.”

Robinson told Friday that priests being able to speak to Benamuckee was “a Cheat” and that it was more likely that they communicated with the Devil. He explained how the Devil constantly attempts to “delude Mankind to his Ruine” and tempt him to destruction. Friday was puzzled by the question of why, if God was omnipotent, he did not simply “kill the Devil, so make him no more do wicked?” When Robinson replied that God’s plan was to kill the Devil on the Day of Judgment, Friday was not satisfied and still insisted that God should kill him now. And if God did not kill him now, did that mean that it was possible for the Devil to repent and be forgiven, just as man could be?

Robinson was at a loss how to satisfy Friday’s curiosity about these types of questions. He realized that, although it was easy for an intelligent creature to understand and appreciate a supreme creator of the universe, “nothing but divine Revelation can form the Knowledge of Jesus Christ.” Robinson prayed to God that Friday’s “Conscience might be convinc’d, his Eyes open’d, and his Soul sav’d.”

Explaining Christianity to Friday, even though not completely successful, helped Robinson to better understand his own beliefs. Not only that, but sharing the joy of Christianity improved his life in other ways: “My Grief set lighter upon me, my Habitation grew comfortable to me beyond measure” because he was “made an Instrument under Providence to save the Life, and for ought I knew, the Soul of a poor Savage.”

Over the next three years, the two men continued to live together and study the Bible. The narrator comments that “The Savage was now a good Christian.” When Robinson read the Bible, Friday asked many questions that helped both men understand the meaning of the scriptures. They never engaged in arguments such as those concerning “Niceties in Doctrines, or Schemes of Church Government” that plagued organized religion because they relied directly on the word of God for instruction.

Friday is a very intelligent man who is asking theological questions that have plagued people for years. If God is omnipotent, why does God not intervene in all sorts of evil and tragedies that fall on mankind?

Friday is a very intelligent man who is asking theological questions that have plagued people for years. If God is omnipotent, why does God not intervene in all sorts of evil and tragedies that fall on mankind?It's interesting that RC assumes that Benamuckee was the Devil or an evil idol, and not a benevolent god. All cultures are trying to explain creation, and good and evil in their own way. But Westerners tend to look for the differences, instead of the similarities, in religious beliefs of people around the world. People everywhere are trying to get answers to the same questions.

I find that Defoe's choice to bring Friday into the novel the way he did in an action scene, following a long period of little action or interaction with other characters, a masterstroke of an authorial decision especially in timing. Even in the period the novel was written, the reader would tend to become bored over repetition and the sense that the novel has few surprises left. Defoe's choice move to the sensational, writing that we feel rather than intellectualize is quite a jolt even to readers now. I feel like I just got woke from a pleasant drowse and am now fully engaged once more. I'm curious Erich if you have any information on how Defoe composed the novel, whether he planned this sudden change to a more visceral writing from the start or made the decision as he went along. It makes little difference. I'm sure most of the readers are pumped up again. And note from all the works we read or entertainments we view, just how difficult it is to get action just right. I commend Defoe on this.

I find that Defoe's choice to bring Friday into the novel the way he did in an action scene, following a long period of little action or interaction with other characters, a masterstroke of an authorial decision especially in timing. Even in the period the novel was written, the reader would tend to become bored over repetition and the sense that the novel has few surprises left. Defoe's choice move to the sensational, writing that we feel rather than intellectualize is quite a jolt even to readers now. I feel like I just got woke from a pleasant drowse and am now fully engaged once more. I'm curious Erich if you have any information on how Defoe composed the novel, whether he planned this sudden change to a more visceral writing from the start or made the decision as he went along. It makes little difference. I'm sure most of the readers are pumped up again. And note from all the works we read or entertainments we view, just how difficult it is to get action just right. I commend Defoe on this.But moving to this next bit of reading, Defoe brings us back to a more rationalizing response. We get anthropology, and history, language and philosophy, so Defoe does not lose his goal of making this novel practical and useful and run off on a thirty page action packed romp. He brings everything back into control, having introduced just enough action to wake us up.

I found the bit of practical philosophy about the knowledge of Jesus Christ needing a divine revelation and though Crusoe cannot give this to Friday, his discourse with Friday reinforces his own beliefs, that Crusoe realizes how the act of teaching accomplishes this. Some of the most interesting material to ponder for us as modern readers is how well Defoe has grasped and explained much of what I call the practical philosophy of the common man.

Connie: "Friday is a very intelligent man who is asking theological questions that have plagued people for years. If God is omnipotent, why does God not intervene in all sorts of evil and tragedies that fall on mankind?

Connie: "Friday is a very intelligent man who is asking theological questions that have plagued people for years. If God is omnipotent, why does God not intervene in all sorts of evil and tragedies that fall on mankind?At first, Robinson pretended not to hear him! That is not an easy question to answer.

It's interesting that RC assumes that Benamuckee was the Devil or an evil idol, and not a benevolent god."

There was also a strong focus on the fact that Friday's people communicated with Benamuckee through the priests rather than directly. RC automatically believes that Friday's religious system has no validity, so there is no question for him that either the priests are lying about communicating with Benamuckee or they are in fact speaking with "a evil Spirit."

Sam: "Even in the period the novel was written, the reader would tend to become bored over repetition and the sense that the novel has few surprises left. Defoe's choice move to the sensational, writing that we feel rather than intellectualize is quite a jolt even to readers now. I feel like I just got woke from a pleasant drowse and am now fully engaged once more."

Sam: "Even in the period the novel was written, the reader would tend to become bored over repetition and the sense that the novel has few surprises left. Defoe's choice move to the sensational, writing that we feel rather than intellectualize is quite a jolt even to readers now. I feel like I just got woke from a pleasant drowse and am now fully engaged once more."Yes, we had the long sections and jumps of several years that Robinson spent for the most part in fear, trying either to avoid or to encounter some of the cannibals. From seeing the first footprint to witnessing periodic visits to rescuing Friday, Robinson has passed around half a dozen years, I believe. As he points out himself, RC made very few innovations since he was so concerned with his safety.

I'm curious Erich if you have any information on how Defoe composed the novel, whether he planned this sudden change to a more visceral writing from the start or made the decision as he went along.

I have not found any information about Defoe's working methods. It seems that little is known; I never see mention in critical writing about his correspondence, for example, or other sources that would help us understand why he made his authorial choices.

I found the bit of practical philosophy about the knowledge of Jesus Christ needing a divine revelation and though Crusoe cannot give this to Friday, his discourse with Friday reinforces his own beliefs, that Crusoe realizes how the act of teaching accomplishes this.

I'm curious as to how RC was able to communicate these kinds of ideas to Friday even if he was making great progress in English; it's a very abstract idea to try to explain to someone in a new language.

Summary of (Chapter 23)

Summary of (Chapter 23)

Once Friday had learned to understand English quite well, Robinson was able to tell him the story of his life, including his shipwreck and how long he had been on the island. He also taught Friday to shoot a gun and provided him with other weapons.

Robinson explained about his homeland and details of his shipwreck. He also showed him the remains of the escape boat that he had been unable to move. After musing for some time, Friday said that a similar boat had come ashore in his country.

When Robinson questioned him more, he explained that he and others had saved seventeen Europeans who had been driven near the shore; those men still lived there. They had made a “Truce” with the local people and, rather than being in danger, the Europeans were supported by the tribe. Friday also said that his people only ate the flesh of enemies taken in battle.

One day, Friday was excited to be able to see his country from the top of the hill. Robinson suspected that, if Friday could return to his country, he would “not only forget all his Religion, but all his Obligation to me” and would return with great numbers of his people to “make a Feast upon me.”

Looking back, the narrator realizes that it was only his “Jealousy” that made him doubt Friday. In fact, Friday was both “a religious Christian” and “a grateful Friend.” Were he to return to his homeland, he would “tell them to live Good, tell them to pray God, tell them to eat Corn bread, Cattle-flesh, Milk, no eat Man again.” When Robinson asked Friday if he would go if he made a canoe for him, Friday said that he would only go if Robinson came with him.

After thinking over what Friday had said, Robinson decided that he had a better chance going to the mainland and attempting to make contact with someone there than staying on the island. Accordingly, he showed Friday his boat where he had hidden it. The two men went for a ride, and Robinson found that Friday was an excellent oarsman. However, the boat was not large enough to attempt a journey to the mainland.

Robinson brought Friday to the large dugout canoe that he had built but been unable to launch, but it was too damaged by time to be of use. Suddenly, Friday began to question Robinson as to why he was trying to convince him to leave the island when he only wanted to be with him. He even offered Robinson a hatchet and asked Robinson to kill him rather than send him away.

After Friday had been reassured that he would never be forced to leave, he and Robinson set to work on a new dugout canoe, one that would be large enough but also that would be close enough to the water for the two men to be able to launch. Working together with Robinson’s tools, they finished in about a month. It took an additional two weeks to inch the enormous boat to the water.

Robinson followed construction of the canoe by fashioning a mast and sail for the ship with sailcloth he had recovered from the wreck. He also made an anchor and cable as well as a steering rudder. These final parts of the project took an additional two months to complete.

With practice, Friday learned to sail and use the rudder competently. He could not master a compass, but he really had no need of it since he was so familiar with the configurations of the stars.

The anniversary of Robinson’s twenty-seventh year on the island arrived, and he observed it as before, with thankfulness to God and the “Care of Providence.” The narrator comments that the three years during which Friday had been Robinson’s companion “ought rather to be left out of the Account” since his life was so much improved.

In addition, the canoe was now ready for an attempt for the mainland, and Robinson was convinced that “I should not be another Year in this Place.” Robinson decided to make a voyage during the last months of the year, when the weather was settled. As the time approached, they began to provision the canoe. One day, Friday was in search of a tortoise when he was terrified to see three canoes arriving at the island, paddled by men who would capture and eat him.

Robinson comforted Friday and encouraged him to be ready to fight, and they armed themselves to prepare for an attack. Once this was done, Robinson went to the top of the hill to assess the situation. He saw that there were twenty-one cannibals with three prisoners whom they intended to eat. Robinson was incensed to see that the cannibals had pulled up on the beach near the creek to have their feast, and he resolved to attack them and kill them all.

With his compass to guide him, Robinson led Friday into the woods to be able to approach their enemies without being detected. As they marched, he reflected once again on his rationale for committing murder against people who had done him no direct wrong. He was not required to act as judge and executioner against these people who had been abandoned by God, and he did not have a valid justification to consider them his enemies. He resolved that he “would not meddle with them.”

When they had approached nearer to the cannibals, Robinson ordered Friday to climb a tree and report what he saw. He said that the cannibals had killed and were eating the first of their victims, while the second was bound and waiting for his execution.

Robinson was shocked to learn that the second victim was to be one of the “bearded Men” who had come to the country. He saw through his telescope that, indeed, the bound man on the beach was unmistakably a European.

Controlling his passion and rage, Robinson maneuvered to within an eighty-yard shot of the cannibals.

Erich, I absolutely agree with all your comments on the relationship between Friday and Robinson.

Erich, I absolutely agree with all your comments on the relationship between Friday and Robinson.I am very uncomfortable reading about Robinson exploiting Friday, in a way.

Building a functioning rudder in these circumstances sounds impressive! I wonder if it's realistic :)

Robinson always thinks the savages would be glad to eat him :)

Things are speeding up, as Sam has noted. And we're pausing on a cliff-hanger! :)

Plateresca: "I am very uncomfortable reading about Robinson exploiting Friday, in a way."

Plateresca: "I am very uncomfortable reading about Robinson exploiting Friday, in a way."Robinson always thinks the savages would be glad to eat him :)

RC also assumes that Friday would immediately kill and eat him if given the chance, even after many months of living together. He seems almost offended that Friday might want to return to live with his own people rather than serving his "Master."

Today is our break day, so there is more time for comments. We will continue with the next section on Tuesday.

Today is our break day, so there is more time for comments. We will continue with the next section on Tuesday.

RC’s trust seems lacking after 3 years of Friday living there. I see that Friday has changed his beliefs and ways bc of RC but RC doesn’t seem to believe Friday’s earnest behavior. I agree that it is hard to see RC treat Friday poorly. I wonder where the other Europeans are from that Friday’s people befriended? Spain, possibly. It’s possible that Friday can speak Spanish and that may be a good reason for why he learned English so easily and well.

RC’s trust seems lacking after 3 years of Friday living there. I see that Friday has changed his beliefs and ways bc of RC but RC doesn’t seem to believe Friday’s earnest behavior. I agree that it is hard to see RC treat Friday poorly. I wonder where the other Europeans are from that Friday’s people befriended? Spain, possibly. It’s possible that Friday can speak Spanish and that may be a good reason for why he learned English so easily and well.

Summary of (Chapter 24)

Summary of (Chapter 24)

As Robinson approached the cannibals, he saw that two of them were preparing to butcher the European captive as the others waited. Robinson instructed Friday to do exactly as he did, and then he set an extra musket nearby, aimed, and fired. Between the two of them, they killed three and wounded five with the first volley. They followed it with swan shot from the second of their muskets, and these shots killed two more and wounded several others. The cannibals were in a panic, and Robinson charged out of his cover towards the captive and frightened the guards away. He called for Friday to come forward and shoot as well, and Friday killed or injured several more with his shot as they paddled away in their canoe.

Robinson quickly untied the captive and gave him water and food to revive him. The man said that he was Spanish, and Robinson supplied him with weapons. The man fell upon some of his captors - who were astonished and frozen from the noise of the guns - and cut them into pieces.

As Robinson reloaded his gun, he saw the Spaniard in close combat with one of the cannibals. As they fell to the ground and the cannibal struggled to wrest away the Spaniard’s sword, the Spaniard pulled out a pistol and shot the man through the body. Friday, who had used all his ammunition, chased down and dispatched several more men with his hatchet. Between Robinson, Friday, and the Spaniard, eighteen cannibals had been killed and only three had escaped in a canoe.

Robinson and Friday were anxious to pursue the three cannibals before they could raise the alarm to their people and return en masse. However, as they stepped into one of the other canoes they found a man there bound and awaiting his turn to be executed. Robinson freed the man and asked Friday to translate for him, but when Friday saw the man he was overjoyed to discover that it was his father.

Friday embraced his father repeatedly and rubbed his arms and legs to help him recover. Robinson was touched by the “Extasy and filial Affection” that Friday demonstrated for the rescued man.

As a result of discovering Friday’s father, they gave up pursuit of the escaped cannibals. However, there was a heavy storm that evening that Robinson believed must have swallowed the three men in their canoe. Friday continued to minister to all of his father’s needs, and they did not neglect to care for the Spaniard as well.

When the men had recovered sufficiently to be moved, Friday paddled them in one of the canoes to the creek near the enclosure. He then retrieved the other abandoned canoe and brought it to the creek as well. Friday and Robinson managed to carry the exhausted men to the enclosure, but they were unable to lift them over the wall. Therefore, Robinson and Friday built a temporary tent for Friday’s father and the Spaniard outside the enclosure. Robinson furnished it with straw beds and blankets.

Illustrations for Chapters 23 and 24

Illustrations for Chapters 23 and 24All images and commentary sourced from the Victorian Web

Upon seeing this boat, Friday stood musing a great while

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Friday clarifies the problems that Crusoe has encountered in boat-construction, including the species of tree he has selected. In his initial attempts, also, Crusoe had built far too big a canoe too far away from where he would have to launch it, so that he wasted months of labor. He is finally successful because he addresses the problem of location and, with Friday's advice, chooses a more suitable species of tree.

Crusoe and Friday felling wood

Matt Somerville, 1863

Commentary: After laboring for himself for twenty-eight years, Crusoe now becomes a colonial foreman or administrator directing the manual labor of his indigenous servant. Crusoe remains ignorant even after all this time of information that is basic for Friday, such as tree species, but on the other hand Friday is able to adapt quite quickly to Crusoe's culture, such as wearing western clothing and using metal tools.

Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a boat

Thomas Stothard, 1782

Inch by inch upon great rollers

Wal Paget, 1891

In this posture we marched out

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget focuses exclusively on the heavily armed Crusoe and Friday as they prepare to intervene in the activities of the cannibals. Both of them are dressed similarly as if to represent the forces of civilization which oppose the barbarous practices of the natives.

Crusoe rescues the Spaniard

Unknown artist, printed in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: Crusoe eschews cultural non-intervention in favor of rescuing a fellow European and Christian. So quickly has Friday picked up the essentials of handling European weaponry and tactics that Crusoe can devote himself to tending the prisoner while his servant puts half a dozen cannibals to flight. Although Friday's calves are bare, the rest of his attire resembles Crusoe's right up to the goatskin cap, so that, as far as the cannibals are concerned, the being discharging his strange and powerful weapon is another god-like outlander rather than the member of a rival tribe. The illustration, then, marks the success of Crusoe's educating Friday to become a thoroughly dependable, Europeanized servant.

Robinson Crusoe rescues the Spaniard

Phiz, 1864

Crusoe rescuing the Spaniard

Sir John Gilbert, 1867

I made directly towards the poor victim

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget emphasizes through Crusoe's tentative approach his fear that the European - the first civilized being with whom he has had contact in twenty-eight years - may be dying. Although the chapter includes the rescue of two prisoners, the European and Carib, nineteenth-century British illustrations tend to focus on Crusoe's aiding the Spanish prisoner. In the background, Friday fires on the cannibals as they flee in their canoe.

Wringing my sword out of his hand

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: The Spaniard, whom Crusoe has discovered to be alive, is about to lose control of his weapon to one of his captors. Crusoe is well in the background to suggest that he may not reach the Spaniard in time to rescue him. As the native wrests the cutlass away from the European, the former captive is just pulling out his pistol.

Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a tent to lodge Friday's father and the Spaniard

Thomas Stothard, 1782

Commentary: Crusoe now has a de facto family, with the muscular Friday working patiently in the foreground while Crusoe holds a torch aloft. In the background is the outward fence of Crusoe's castle, apparently constructed of basket-work. Crusoe has quickly built relationships with these strangers as they work together to tame the wilderness and build a home. In the image, representatives of competing world powers work together for the common good, with Friday - who exemplifies physical perfection - in the center of the action.

What an action-packed chapter!

What an action-packed chapter! I wonder if the savages really would want to return en masse, or, on the contrary, be scared away from the island.

Thank you for the illustrations, Erich! I like Wal Paget's Friday best, he's so full of character; and I also enjoyed how this illustrator reflected Robinson's ageing in this artwork.

The quote below is very telling, I think in terms of what makes this book so popular even to this day and almost sums what Defoe has been offering his readers throughout, which is a depiction of the dream of success as achievable through will, hard work, and trust that a higher power will reward one who follows these precepts. it is important to consider the quote in relation to our own goals. So whether read by a mercantile novice, a Puritan dreamer, or anyone with their own dreams, following in the years to come, the idea if betterment and success is reinforced.

The quote below is very telling, I think in terms of what makes this book so popular even to this day and almost sums what Defoe has been offering his readers throughout, which is a depiction of the dream of success as achievable through will, hard work, and trust that a higher power will reward one who follows these precepts. it is important to consider the quote in relation to our own goals. So whether read by a mercantile novice, a Puritan dreamer, or anyone with their own dreams, following in the years to come, the idea if betterment and success is reinforced. My island was now peopled, and I thought my self very rich in Subjects; and it was a merry Reflection which I frequently made, How like a King I look’d. First of all, the whole Country was my own meer Property; so that I had an undoubted Right of Dominion. Idly, My People were perfectly subjected: I was absolute Lord and Lawgiver; they all owed their Lives to me, and were ready to lay down their Lives, if there had been Occasion of it, for me. It was remarkable too, we had but three Subjects, and they were of three different Religions. My Man Friday was a Protestant, his Father was a Pagan and a Cannibal, and the Spaniard was a Papist: However, I allow’d Liberty of Conscience throughout my Dominions: But this is by the Way.

These last two links are two recent Guardian reviews that while having nothing to do with our book, offer some thoughts, which I consider worth considering in contrast with Crusoe's. I don't suggest an agreement with either author's views anymore than I agree with Crusoe's; I just think they are interesting in comparison

https://www.theguardian.com/environme...

https://www.theguardian.com/books/202...

Plateresca: "What an action-packed chapter!

Plateresca: "What an action-packed chapter! I wonder if the savages really would want to return en masse, or, on the contrary, be scared away from the island."

That is a good question. Robinson seems to ponder this from time to time, but it would be a good topic to bring up with Friday. Friday probably knows many things that could help Robinson escape the island or make his stay there more comfortable. We have seen Robinson introduce Friday to European foods, objects, and concepts, but so far he has only learned how to make a proper dugout canoe from him.

Sam: "... a depiction of the dream of success as achievable through will, hard work, and trust that a higher power will reward one who follows these precepts."

Sam: "... a depiction of the dream of success as achievable through will, hard work, and trust that a higher power will reward one who follows these precepts."Necessary to this structure is the idea of class mobility that accompanied the rise of capitalism (and the novel). It is important that Robinson Crusoe appeared when it did, as it was becoming more possible to imagine having the types of adventures he does.

RC has mused about his "kingdom" earlier with his animal subjects, and now he does the same thing with the people he has collected around him. His tone is somewhat lighthearted and whimsical, but underneath it is apparent that he finds it quite natural to think of himself as a "master" or a "king."

Summary of (Chapter 25)

Summary of (Chapter 25)

It amused Robinson to think of himself as a “King” with a “Right of Dominion” over the island who allowed “My People” “Liberty of Conscience.” The two men he and Friday had rescued gradually gained strength, and Robinson butchered a goat and stewed meat for them with some of his grain. Friday interpreted for his father and also for the Spaniard, who spoke Friday’s native language fairly well.

Robinson ordered Friday to return to the site of the battle to retrieve their weapons, bury the dead and “the horrid Remains of their barbarous Feast,” and remove all other traces of the struggle. That accomplished, Friday translated for Robinson as he interviewed his father.

Friday’s father did not believe that the escaped cannibals had survived the storm on the night of his rescue. He was sure that they had either been lost at sea or driven to the south where they were “as sure to be devoured as they were to be drowned if they were cast away.” If they did manage to get home, they would tell their people that the others had been killed by thunder and lightning and that there had been two spirits from heaven come to destroy them.

Robinson was not completely reassured by the native man’s words and remained vigilant. Little by little, his fears relaxed and he returned his attention to the possibility of a voyage to the mainland. Friday’s father said that Robinson would “depend upon good Usage from their Nation on his Account, if I would go.” However, the Spaniard explained that, although he and the other European castaways lived at peace with the natives, they struggled mightily for their subsistence.

The Spaniard went on to tell Robinson about how he came to be shipwrecked in that part of the world on a voyage to Havana. The survivors had almost no supplies and no way of escaping their situation. Robinson considered whether he could help the men were they to come to his island, but he worried about being betrayed and imprisoned in “New Spain.” He told the man that “I had rather be deliver’d up to the Savages, and be devour’d alive, than fall into the merciless Claws of the Priests, and be carry’d into the Inquisition.” He was certain that with so many men to help they could build a serviceable boat, but only if he were not deceived.

The Spaniard reassured Robinson that the castaways were so weak and desperate that they would never think of betrayal. He was certain that they would be willing to swear total obedience to Robinson, and he offered to parley with them and bring Robinson a written contract to guarantee their allegiance. He also swore himself to follow Robinson’s orders and “take my Side to the last Drop of his Blood, if there should happen the least Breach of Faith among his Country-men.”

However, the Spaniard advised that Robinson should build up his stocks of grain over the next six months before inviting the other fourteen survivors to join him. If the men were brought to the island with insufficient food, “Want might be a Temptation to them to disagree, or not to think themselves delivered, otherwise than out of one Difficulty into another.” Therefore, the four of them set to work clearing additional farmland and planting almost all of the grain that Robinson had available.

With greater numbers and mutual protection, Robinson and the other men roamed the island more freely than Robinson had been wont to do. With the picture of a boat constantly in mind, Robinson set the others to work felling trees and creating planks. He also turned his mind to increasing his flock of goats, and he and Friday took turns hunting mother goats with young kids so that they could add the kids to the flock. On top of that, Robinson dried huge amounts of raisins in anticipation of the coming men.

The grain crop was a success, and they managed to increase their stocks of grain ten-fold. To store the additional grain, they wove more wicker baskets.