Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Robinson Crusoe

All Around Dickens Year

>

Robinson Crusoe (end) by Daniel Defoe - Group Read (hosted by Erich)

We've discussed how Robinson is not interested in Friday's real name; it seems he's not interested in anybody's name, hence 'the Spaniard' and 'the old savage, the father of Friday'. Sweet.

We've discussed how Robinson is not interested in Friday's real name; it seems he's not interested in anybody's name, hence 'the Spaniard' and 'the old savage, the father of Friday'. Sweet.I agree with what Lori said, too, about the meeting between father and son.

Is Friday's mother alive, does he have any other relatives, might they not be in danger now etc — none of these questions preoccupy our hero.

I hope the other Spaniards are decent people, of course (the one we know of seems to be nice, which is a relief!), but it's a bit dubious to me that 'our' Spaniard first promised those others would behave well, but then said they probably wouldn't if there's not enough food for everybody. If they are to undertake a long voyage, there will surely be challenges along the way.

I've been out of town without access for the past fortnight. There are so many comments to catch up on. I've missed the discussion.

I've been out of town without access for the past fortnight. There are so many comments to catch up on. I've missed the discussion. I also find that as we continue to read, I don't really like Robinson very much. He looks down on people and disregards animals. I realize that his attitudes are from the time he is from but it makes for some uncomfortable reading. I suppose that's a good thing, as it shows that we've moved closer to inclusion and acceptance of all.

It's getting quite exciting on the island now. The added people and events have added some interest to the story. It was getting a bit old to read about only Robinson, his actions and his thoughts for so many years.

Plateresca: "it seems he's not interested in anybody's name, hence 'the Spaniard' and 'the old savage, the father of Friday'."

Plateresca: "it seems he's not interested in anybody's name, hence 'the Spaniard' and 'the old savage, the father of Friday'."He doesn't seem to give any thought to whether the Spaniard or the Caribs would perhaps like to return to their own respective homelands. He has saved all of the others, so he assumes that he is naturally the Father or King or Master and that they naturally would want to serve him for their entire lives.

Populating the island with additional people would enable Robinson to construct and captain a boat that could take them away from the island. There is self-interest both in having those people sworn to follow him and in using their labor to make his escape.

Petra: "I've been out of town without access for the past fortnight. There are so many comments to catch up on. I've missed the discussion.

Petra: "I've been out of town without access for the past fortnight. There are so many comments to catch up on. I've missed the discussion. I also find that as we continue to read, I don't really like Robinson very much. He looks down on people and disregards animals."

Welcome back to the discussion, Petra! I was pondering the question we considered earlier, about why we continue to read Robinson Crusoe. I find the most recent parts that are concerned with fighting off cannibal attacks and saving captives less interesting than the earlier parts about survival on the island, and that is where it is easier for me to imagine myself in those situations. I feel less affinity with Robinson in his relationships with people (and animals) than I do with the more generally human aspects of surviving in difficult conditions and dealing with extreme solitude.

Summary of (Chapter 26)

Summary of (Chapter 26)

The strangers spent so much time in conversation and exploring the area that their boat was stranded on the beach as the tide receded. As some of the men struggled in vain to move the boat, Robinson overheard them using English to one another.

He knew that their boat would be fast aground until the next high tide in several hours, so he decided to observe them more closely once it got dark and he could move more safely. In the meantime, Robinson and Friday armed themselves for battle with as many of their weapons as they could prepare.

Although Robinson had planned to wait until after dark to approach the men, he saw that the three prisoners had gathered at some distance from the others, and he resolved to reveal himself to them. He stealthily marched near to the men and called out to them in Spanish.

The prisoners were shocked at Robinson’s wild appearance and looked as if they might flee, so he addressed them again, this time in English. The men could not believe their eyes and said that Robinson must be “sent directly from Heaven.” Robinson reassured them that he was a man and offered to help them if he could. One of the prisoners, the former Commander, explained that their captors had mutinied against him and planned to maroon him with his mate and a passenger on the island.

The captain went on to tell Robinson that the mutineers were sleeping under some nearby trees. They had two guns with them and one more in the boat. When Robinson asked if he should take the easier course and kill them all or if he should attempt to take them captive, the captain said that two of them were “desperate Villains” who should not be spared but that he believed the others would obey him if their leaders were killed.

Robinson offered to rescue the men, but only on condition that they gave him command of the ship if it was recovered and, if not, swore to “live and dye with me in what Part of the World soever I would send him.” He wanted the captain to promise that “you will not pretend to any Authority here” and that he would bring Robinson to England if they secured the ship.

Having received his promises, Robinson supplied the three men with a musket each with powder and ammunition and asked the captain what he thought should be done. When the captain deferred to Robinson’s judgment, the latter said that the best course would be to surprise the men while they were asleep, killing as many as possible with the first volley - relying wholly “upon God’s Providence to direct the Shot” - and then ordering the surrender of the survivors.

The captain was hesitant to kill any but the ringleaders of the mutiny if avoidable, so he and the other armed prisoners approached the resting mutineers and attacked them before they could react. In the attack, they killed one of the leaders, wounded the other, and demanded the surrender of the remaining men. The captain decided to spare the lives of those who promised to serve him and return the ship to Jamaica, but Robinson insisted that the men be tied up while they were on the island. Three men who had straggled away from the group earlier returned, vowed obedience also, and were bound with the others.

Once the mutineers had been subdued, Robinson told the captain his entire history and how he had survived on the island. Strongly affected, the captain reflected that “I seem’d to have been preserv’d there, on purpose to save his Life.”

Robinson brought his new friends to his fortification and showed them how he had managed to conceal it with the fence of living trees. There, they discussed how they might go about regaining control of the ship. The captain explained that on the ship there were still twenty-six mutineers who were “harden’d in it now by Desperation” and who knew that, were they captured, they would be executed or transported.

Robinson realized that if the men who had come by boat did not return to the ship, the mutineers would eventually send a party to investigate. In the meantime, he ordered that the boat on the beach be emptied and then staved in so that it was unusable.

As predicted, the ship lowered a second boat and Robinson saw through his telescope that it contained ten armed men. The captain was able to distinguish three of the men who were “very honest Fellows” who had only joined the mutiny out of fear, but the others were “as outrageous as any of the Ship’s Crew.”

The captain was full of doubt as to whether they would be able to overcome the number of men with weapons who were coming ashore, but Robinson reassured him that “Men in our Circumstances were past the Operation of Fear.” He calmly proclaimed that, “depend upon it, every Man of them that comes a-shore are our own, and shall die, or live, as they behave to us.”

Before the mutineers arrived, Robinson had the prisoners divided into smaller groups, with three held in the cave and two in the enclosure. Two prisoners who were recommended by the captain were given liberty and arms to fight against the mutineers, raising the number of defenders to seven men.

When the mutineers landed on the beach, they were puzzled and surprised to see the condition of the first boat. They shouted and fired volleys into the air but received no answer. After conferencing, the men retreated to the ship.

After some time, the mutineers returned to the island, and this time they left three of their men in the boat while the other seven searched for the imprisoned men. Finding no sign of them, the searchers sat together beneath a tree to consider what they should do. The captain suggested to Robinson that they wait until the mutineers fired another volley into the air; if they all did so simultaneously, they could be captured easily before they could reload. However, that circumstance did not occur.

Robinson wanted to keep the men from giving up the search and returning to the ship, which they would then sail away. Therefore, when the seven searchers had given up and were walking toward their anchored boat, Friday and the captain’s mate shouted to them from the direction of the creek. The men headed toward the voices but were stopped by the creek. Believing that their fellows had called to them from the other side of the creek, they called to the men on the boat to help them across.

Two men remained with the boat as the rest continued the search. Robinson and the others surprised the two guards before they could resist and took them prisoner, securing the boat. Friday and the mate continued to lead the mutineers on a search all around the island, leaving them lost and exhausted when night fell.

Eventually, the lost mutineers found their way back to the boat in the creek, but they were dumbfounded to find their boat abandoned and aground. They began to exclaim that the island must be either enchanted or inhabited by murderers, and they wrung their hands in despair.

As the mutineers wandered about near the boat, calling periodically to their missing comrades, Friday and the captain crept as close as they could to the men before opening fire. The boatswain - one of the ringleaders - was killed with a companion instantly, and in the confusion another man escaped.

One of the mutineers who had been captured negotiated a surrender with those who remained, and the captain promised to give quarter to all but Will Atkins, who had “used [the captain] barbarously” during the mutiny. The captain said that Atkins must “lay down his Arms at Discretion, and trust to the Governour’s Mercy, by which he meant me.”

This was an exciting section! Robinson is so dry when he describes the consternation and exhaustion of the mutineers; I had to laugh.

This was an exciting section! Robinson is so dry when he describes the consternation and exhaustion of the mutineers; I had to laugh.Now, Robinson has the power of life and death over Will Atkins. During the battles, RC has favored massacring everyone and letting God sort it out, while the captain has been more cautious and hesitant about taking human life. Would RC be willing to let Atkins live if Atkins simply swore loyalty to him? That hasn't been enough for the more suspect former mutineers, whom Robinson "was not against" sparing their lives but whom he insists must be "bound Hand and Foot while they were upon the island."

It was such an action packed chapter! Someone probably could have made a two-hour movie from that chapter alone. Considering how many men had guns, they were lucky that the body count was not larger.

It was such an action packed chapter! Someone probably could have made a two-hour movie from that chapter alone. Considering how many men had guns, they were lucky that the body count was not larger.

To tell the truth, I also enjoyed the story more when it was more philosophical.

To tell the truth, I also enjoyed the story more when it was more philosophical.Robinson seems to be enjoying himself! Once again, he demonstrates his super-resourcefulness. (Erich, I still disagree he's meant to represent an ordinary man! One of your arguments was, if I understood correctly, that you can imagine yourself in his shoes; well, I think you are by no means ordinary either :) And look, everybody is treating him as their superior. The way other characters treat the main character is always a very telling characterization method).

It is confusing, though, that there is now somebody else also called Robinson. I think writers stopped naming more than one character with the same name at some point.

It is interesting that people swear they will behave well, and the others believe them. Well, I understand it is in everybody's interest to cooperate right now.

It seems a crazy thing for one person to tell the other something along the lines of, 'You were saved so that I might be saved eventually'.

I agree with Connie about the body count; we should thank the Captain that it's as low as it is now!

Plateresca: "And look, everybody is treating him as their superior. The way other characters treat the main character is always a very telling characterization method."

Plateresca: "And look, everybody is treating him as their superior. The way other characters treat the main character is always a very telling characterization method."To the men he has rescued, RC must seem almost godlike. He has shelter, tools, animals, crops, supplies, weapons, and his "Man" Friday. The others treat him as their superior, but the captain does disagree with his idea to kill everyone possible and suggests a more balanced plan.

Until this chapter, RC's strategies for dealing with dangerous people have been: run and hide, observe from cover, or attack and kill. He hasn't tried stealing a canoe or scaring away the cannibals by making strange noises, for example. The fact that, as you and Connie point out, the body count is low is due more to the captain's mercy than to RC's forbearance.

Our book has set me thinking about the basis of authority. When it was just Robinson and his animal friends or Robinson and Friday, it was easy for Robinson to be the "King" of the island and his "family." When the Spaniard and Friday's father join the group, it is no longer a family but a sort of Republic with different ethnic and religious identities. When the captain appears, he defers to RC's judgment and swears his loyalty, but he is another potential authority figure (Friday's father is also a competing authority figure for RC's control over Friday). Now that more men are on the island, RC is very concerned about maintaining control; he requires that they swear complete loyalty before he will set them at liberty. But there is also the mate, who owes his allegiance to the captain as well as to RC. Relationships are becoming more complex...

Will Robinson be able to maintain control without resorting to compulsion and coercive persuasion? As we see from the fact that the captain's crew has mutinied, authority without authoritarianism is a very thin line. Historically, most mutinies are fueled by harsh living conditions, lack of pay, or excessive punishment = poor leadership. We don't know exactly why the captain's crew mutinied, but it suggests that RC's leadership style (swear to follow me if you want freedom and food) is inadequate.

Summary of (Chapter 27)

Summary of (Chapter 27)

As Robinson considered how he and the others might manage to gain control of the ship, the captain lectured the captives about “the Villany of their Practices” and “the farther Wickedness of their Design.” He explained that what the mutineers thought was an uninhabited island was governed by an Englishman who had the power of life and death over them. He lied that Robinson planned to send the followers to England to face justice and that Will Atkins would be hanged in the morning.

All of the captive mutineers begged for their lives, and Robinson saw that the men could be allies to help him take over the ship. To keep the prisoners in awe of him and give the impression that Robinson commanded a formidable army, Robinson never showed himself but only spoke to the captain, while the captain referred to him as “his Excellency” and made a show of being at his beck and call.

Robinson separated Atkins and two other leaders from the other prisoners and had them brought to the cave, while he kept the other seven confined in his “Bower.” The next morning, the captain told the prisoners in the bower that, if they helped regain control of the ship, he would request a pardon for them. They readily agreed to the plan.

To help ensure the loyalty of the mutineers, Robinson selected five of them for the attempt and told them that the other two plus the three in the cave would be held as hostages and executed if the mutineers were to betray him. Robinson and the captain agreed that the captain would take nine men with him to take over the ship while Robinson and Friday stayed behind to guard and care for the prisoners. To preserve the illusion of a powerful “Governor” overseeing the island, they told the men that Robinson was the Governor’s assistant.

After they had repaired the staved in boat, the captain divided his men between the two boats and they rowed out to the ship at midnight. As one of the former mutineers kept the men on deck in conversation, the captain and first mate quietly boarded the ship and secured the men on deck. Then more boarded and took others of the crew prisoner.

The “Rebel Captain” and three followers defended themselves from a rear cabin as the first mate and three others stormed in. Shots from the mutineers injured the mate and two others, but the mate then managed to shoot and kill the leader, ending the battle. The men on the ship fired guns to signal Robinson that the ship was taken, and Robinson, exhausted, fell asleep.

Robinson was awoken the next morning by the captain, who embraced him and exclaimed, “My dear Friend and Deliverer, [...] there’s your Ship, for she is all yours, and so are we and all that belong to her.” Robinson was overcome with joy and thankfulness to “a secret Hand of Providence governing the World, and an Evidence, that the Eyes of an infinite Power could search into the remotest Corner of the World, and send Help to the Miserable whenever he pleased.”

The captain brought ashore a variety of drinks, food, and even a suit of European clothing. To Robinson after so many years, the clothes at first felt “unpleasant, awkward, and uneasy.”

Next, the men discussed their plans for leaving. They agreed to leave the two most “incorrigible and refractory” mutineers behind them on the island rather than attempt to transport them in irons. Robinson spoke to them along with the three others who had been imprisoned in the cave and offered them the choice of either staying on the island or going to England to face justice there. Without thinking twice, the men agreed to be marooned on the island.

The captain went to the ship to prepare for the voyage and had the dead leader of the mutineers hanged at the yard-arm so that the others would see his fate. Robinson then spent his last night on the island instructing the men they were to leave behind about how he had managed to survive for so many years. He gave them guns, powder, ammunition, and supplies along with instructions. He also told them to expect the sixteen Spaniards to arrive soon, and he left a letter waiting for them.

The next day, Robinson boarded the ship, and they prepared to sail. Before they could leave, however, two of the marooned men swam out to the ship and frantically begged to be taken aboard because they feared being murdered by the other three. The captain reluctantly agreed, and after the men were punished soundly they would reform.

Before departing, Robinson visited the remaining men on the beach and promised them that he would send assistance to them if he could. He took with him as mementoes his goatskin cap, umbrella, parrot, and the money he had recovered from the shipwrecks.

Robinson at last returned to England after twenty-eight years on the island and a total of thirty-five years away from home.

Illustrations for Chapters 25-27

Illustrations for Chapters 25-27All images and commentary sourced from the Victorian Web

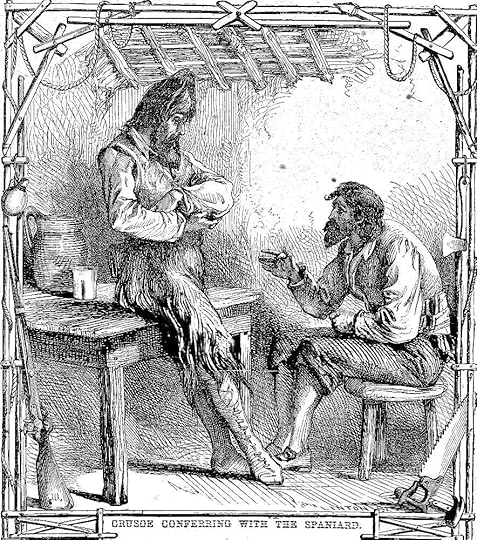

Crusoe conferring with the Spaniard

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: The reunion of Friday and his father would have been a far more animated and heart-warming illustration, but Crusoe's conversation with the Spaniard compels the reader to attend to the plot, whose trajectory must now include returning Crusoe to Europe. Despite his ordeal, the former prisoner is well dressed, with a linen shirt, silk waistcoat, untattered breeches, hose, and pumps, all contrasting Crusoe's island dress of goatskin breeches and animal-hide buskins. The conference apparently occurs in Crusoe's cave, with the now-familiar table and chair and a rustic shelf just above Crusoe's head.

Crusoe sees an English ship

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

My eye plainly discovered a ship lying at an anchor

Wal Paget, 1891

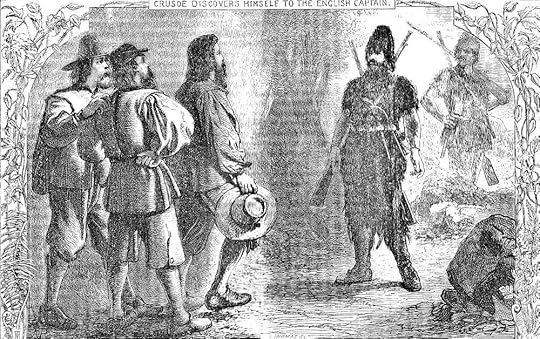

Crusoe discovers himself to the English captain

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: The Cassell image smacks of theatricality, not only in its curtainlike side borders, but in the disposition and poses of the characters. The slight backdrop conveys little sense of depth or perspective, drawing the eye forward to the well-armed, goatskin-clad Crusoe and the captain, who has just doffed his hat out of respect for this strange apparition. Although Friday looks on curiously from the rear, the artist draws the viewer's attention to the more sharply defined figures of the sailors, individualized by their postures and attitudes. The man on the left grips his companion's shoulder, anxious to hear what the stranger has to say and learn whether he brings relief or further danger. The other sailor keeps his hands on his hips in a more defiant attitude, but he too stares pointedly at Crusoe.

The Mutineers

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: Since the illustrator depicts the prisoners in clothing worn by members of the upper classes and the mutineers in ordinary seamen's uniforms, he seems to imply that the mutiny runs along class lines. The border contributes to the reader's sense of suspense because it contains weapons and contrasting flags. A British naval ensign (upper left) appears opposite the skull-and-cross-bones pirate flag (upper right), reinforcing the reader's impression that both sides are about to engage in combat with weapons ranging from swords, cutlasses, and axes (left border) to a variety of firearms (right border).

"What are ye, gentlemen?"

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget minimizes the jungle setting, placing tropical plants around Crusoe only, left of center. The artist has captured the moment before the Captain bursts into tears of gratitude, so that the illustration is largely devoid of emotion except for the curiosity of the English sea-captain and his men.

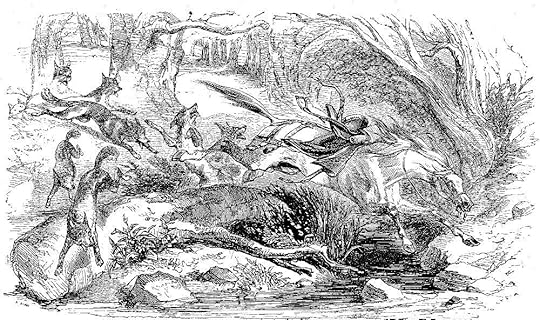

The Mutineers Overpowered

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: The realistic treatment of the mutineers juxtaposes the humbled and utterly terrified ordinary seamen groveling on the ground and the aggressive Captain and his mates, threatening instant death from their firearms. The artist provides only a generalized island setting as a flat theatrical backdrop in order to focus the reader's attention on the captain and the leader of the mutineers.

They begged for mercy

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: In the illustration, neither Crusoe nor Friday appears within the frame; rather, the three armed men in the rear of the picture are the captain and his two loyal subordinates — Crusoe has apparently been watching the action from a distance, and only arrives after the captain's men have shot two of the mutineers: "By this time I was come" (184). However, only once Crusoe has arrived, presumably with Friday, do the three remaining mutineers capitulate and beg for mercy. Consequently, the picture is a distortion of the scene as Defoe presents it in that Crusoe should be among the figures at the back of the illustration since he sees the scene from the perspective of the captain and his supporters rather than, as in Paget's illustration, from behind the mutineers.

He made Robinson hail them

Wal Paget, 1891

Death of the Rebel Captain

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: The realistic treatment of the conclusion of the mutiny in the image implies that the forces loyal to the captain have employed explosives to blow down the stout door of the round-house and in the process have eliminated the threat which the leaders of the mutiny pose. In fact, as the text makes plain, an exchange of gunfire precedes the moment depicted. The mate, though, leading the loyalist forces, does not even appear to have been wounded in the fray.

Shot the new captain through the head

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget has selected one of the book's most violent episodes, the shooting of the leader of the mutiny. The artist sensationalizes the scene below decks in which the first mate puts a bullet through the head of the ringleader, firing at nearly point-blank range, whereas the earlier Cassell's treatment shows the head mutineer already dead as the loyal sailors break into the round-house.

The Captain hung at the Yard-arm

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: In this tranquil scene, the substantial corpse of the rebel leader in "Death of the Rebel Captain" becomes a diminutive scarecrow whom five sailors in the longboats matter-of-factly observe as (presumably) they load supplies for the transatlantic crossing.

I showed them the new captain hanging from the yard-arm of the ship

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: As the island plenipotentiary Crusoe has exerted his authority as "governor" of the island, lending rather than giving the captain and his subordinates firearms and insisting that his authority be superior on the island. Paget disrupts the visual continuity by dressing Crusoe in the European fashion of the late seventeenth-century, signifying Crusoe's social reintegration. In this illustration he is, in fact, an entirely different Crusoe, re-made in the fashion of the late seventeenth century, in a long leather surcoat, feathered hat, stockings, and buckled shoes. Friday does not appear in "island garb" again, having disappeared in the mutiny sequence,

This is the point at which most recent editions end the story. However, since we are following the original edition, we will have a few more days of before we complete our group read.

This is the point at which most recent editions end the story. However, since we are following the original edition, we will have a few more days of before we complete our group read.Looking forward to your comments!

Friday has participated in the action in the recent chapters: freeing the captain and attacking his captors, leading the men from the second boat on a wild goose chase all over the island, guarding men at the cave. Meanwhile, the Spaniard and Friday's father have been on a mission to the other Spanish castaways.

Friday has participated in the action in the recent chapters: freeing the captain and attacking his captors, leading the men from the second boat on a wild goose chase all over the island, guarding men at the cave. Meanwhile, the Spaniard and Friday's father have been on a mission to the other Spanish castaways.Has Friday left the island with RC without consulting his father or even saying goodbye? It surely could have been possible to wait for a few more days before leaving in the ship?

RC has left a note for the Spaniard, who may arrive with sixteen more people to support. Now, the island is in the hands of the three most bloodthirsty and desperate mutineers. They have weapons, ammunition, and plenty of powder. Will they welcome Friday's father and seventeen Spaniards warmly, or will they murder or enslave them?

What is RC's responsibility to the island and the people there? He has said that he will send assistance if possible, but what would that assistance be except delivering the criminals to justice in England, which he could have done himself? He likes the idea of leaving them there rather than having to keep them in fetters for the voyage to England, but whom is he helping?

Wouldn't it make more sense for RC to take all of the prisoners and leave Friday there to welcome his father and the Spaniards? He could teach the Spaniards how to survive and then return with his father to his own people. Or does the fact that Friday is RC's "Man" mean that it goes without saying that he should accompany RC?

We will take a two-day break from reading before we begin the last sections on Tuesday. There is plenty of time for discussion!

We will take a two-day break from reading before we begin the last sections on Tuesday. There is plenty of time for discussion!

I've also wondered about the mutiny on the Captain's ship. The captain explains it by the wickedness of some of the people there. It is said that if the mutineers' crime gets known in England, they will be hanged, so they must have had their reasons for deciding to what, become pirates from now on? Since they can't go back to England... I don't know how easy it would be for them to get employment in some other country; wouldn't captains everywhere be wary of mutineers//pirates on board?

I've also wondered about the mutiny on the Captain's ship. The captain explains it by the wickedness of some of the people there. It is said that if the mutineers' crime gets known in England, they will be hanged, so they must have had their reasons for deciding to what, become pirates from now on? Since they can't go back to England... I don't know how easy it would be for them to get employment in some other country; wouldn't captains everywhere be wary of mutineers//pirates on board?I can't believe Robinson has left all that he has constructed with such care to the worst offenders! I can't believe he decided to just ignore the Spaniards that he had invited! And what about Friday?!

As always, very interesting illustrations and commentary, thank you for choosing and including them, Erich!

But I'm really shocked by this chapter. After all the minute descriptions of how Robinson built this or that, of how they were chasing the mutineers, etc, Defoe has just wrapped up this bit in a couple of words, one moment Robinson is showing the mutineers how to grow crops (it's that easy, right?), and the other he's in England!

Robinson left guns and powder with the mutineers. I would worry about the Spanish castaways and Friday's father when they return. Will they be made servants/slaves of the mutineers who hold the guns, the food, and the shelters? Like Erich and Plateresca, I wonder what came over Robinson to make such a quick decision and put so many people in danger.

Robinson left guns and powder with the mutineers. I would worry about the Spanish castaways and Friday's father when they return. Will they be made servants/slaves of the mutineers who hold the guns, the food, and the shelters? Like Erich and Plateresca, I wonder what came over Robinson to make such a quick decision and put so many people in danger.

I have to agree with both Plataresca and Connie. And I also can’t imagine that this would have been a sufficient ending with no indication of what happens next. It is rather abrupt. RC had to be attached to all that he made so I’d think he might have a last moment to put it all behind him. A reflective prayer or something.

I have to agree with both Plataresca and Connie. And I also can’t imagine that this would have been a sufficient ending with no indication of what happens next. It is rather abrupt. RC had to be attached to all that he made so I’d think he might have a last moment to put it all behind him. A reflective prayer or something.

I'm not happy with this chapter either. It doesn't lift Robinson in my estimation. I am trying to keep a neutral stance but I don't really like him. He's got a disregard for others and his surroundings that I find hard to disregard. It's all about him and his needs & wants. Sometimes in this novel that attitude is justified. As in changing the island to help him live and survive. But sometimes it just shows his sense of superiority and disregard for others and his surroundings.

I'm not happy with this chapter either. It doesn't lift Robinson in my estimation. I am trying to keep a neutral stance but I don't really like him. He's got a disregard for others and his surroundings that I find hard to disregard. It's all about him and his needs & wants. Sometimes in this novel that attitude is justified. As in changing the island to help him live and survive. But sometimes it just shows his sense of superiority and disregard for others and his surroundings. In this chapter he's shown no concern for the Spaniards or Friday's father. Or Friday...who isn't mentioned. What's to become of him?

He's left the island to mutineers, who may not treat the others well when they arrive.

I'm not sure it such an abrupt decision. From time to time over the decades he has thought of how to get off the island. And his whole idea for sending Friday's father and others was to scope out how the Spaniards were doing on Friday's island and if he would be safe there among others like himself. I was more wondering about his being torn between leaving to find community with the Spaniard's and now his increasing population on his own island where he thinks of himself as king. But now that he has exacted promises from the Captain about his demands and authority, it makes the decision of how to move forward easier to him.

I'm not sure it such an abrupt decision. From time to time over the decades he has thought of how to get off the island. And his whole idea for sending Friday's father and others was to scope out how the Spaniards were doing on Friday's island and if he would be safe there among others like himself. I was more wondering about his being torn between leaving to find community with the Spaniard's and now his increasing population on his own island where he thinks of himself as king. But now that he has exacted promises from the Captain about his demands and authority, it makes the decision of how to move forward easier to him.I was happy to see that he was concerned about how those left behind would live, teaching them about the crops and how to milk the goats along with leaving weapons for defense. It speaks to how his character has evolved over his 28 years on the island.

I do wonder that RC didn't seem to consult Friday about this plan, since his father would be returning (hopefully) back to the island with other castaways. Is Friday really more bonded to RC now than to his own Father and people? Is he afraid he wouldn't be safe if he returned to his own nation? Does he trust RC so much that he is willing to go to an unknown country and life ahead?

Erich: the illustrations and commentary were much appreciated. Also why do the newer editions end on this note?

Chris wrote: "Also why do the newer editions end on this note?"

Chris wrote: "Also why do the newer editions end on this note?"Erich, that's a question in my mind, too; until you shared the fact, I had no idea that some of the versions in print are actually mutilated editions missing the last part. (I'm glad that when I read it, I was able to get the whole book, the way that Defoe actually wrote it!)

Lori wrote: "I misunderstood the ending so thanks for that question Chris."

Lori wrote: "I misunderstood the ending so thanks for that question Chris."It makes more sense that Defoe did not end it here. The right question is why modern versions delete what comes after?

Lori: "It makes more sense that Defoe did not end it here. The right question is why modern versions delete what comes after?"

Lori: "It makes more sense that Defoe did not end it here. The right question is why modern versions delete what comes after?"That is something that we can think about as we read the last sections: what would we do as editors? Also, I've surveyed several modern editions and see that most DO include the last sections. One edition I have seems targeted for children, so that was probably a factor.

Defoe also followed this book with The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, so it may be that he had that in mind and the ending reflects that. We'll see!

Plateresca: "I can't believe Robinson has left all that he has constructed with such care to the worst offenders! I can't believe he decided to just ignore the Spaniards that he had invited! And what about Friday?!"

Plateresca: "I can't believe Robinson has left all that he has constructed with such care to the worst offenders! I can't believe he decided to just ignore the Spaniards that he had invited! And what about Friday?!"Connie: "Like Erich and Plateresca, I wonder what came over Robinson to make such a quick decision and put so many people in danger."

I was surprised at that also, although I appreciate Chris's point that at the time Robinson sent the Spaniard and Friday's father to meet the other Spaniards, there was no English ship near the island. Had the English ship not come, there would have been a different plan. RC's original plan was to take advantage of the additional labor from the new arrivals to build and manage a ship that would be large enough for a long voyage back to civilization.

But as Petra points out: "It's all about him and his needs & wants. Sometimes in this novel that attitude is justified. As in changing the island to help him live and survive. But sometimes it just shows his sense of superiority and disregard for others and his surroundings."

I've felt this way about RC several times, although I can understand that after all this time he wants to save himself more than to take care of others. As Chris notes, he took the time to instruct the castaways about how to survive, so he is not completely inconsiderate. But he also doesn't think about the fact that these desperate criminals will almost certainly harm the others when they arrive. I wonder if he would have made different choices if he were expecting the arrival of eighteen Englishmen instead of seventeen Spaniards and a Carib?

He explains that his decision to leave the men (comparatively) free is based on the fact "That when they were taken, the Captain promis'd them their Lives." However, this is when he is toying with them, leading them to believe that he is considering executing them himself. He and the Captain are playacting during this entire scene, with the Captain pretending to demand that the prisoners be returned to England to face execution and RC playing the lenient GoodCop. Part of the reason for this is to "scare them straight" (which we see does not work), but it actually pleases RC to have this kind of power over people.

Chris: "I was more wondering about his being torn between leaving to find community with the Spaniard's and now his increasing population on his own island where he thinks of himself as king."

Chris: "I was more wondering about his being torn between leaving to find community with the Spaniard's and now his increasing population on his own island where he thinks of himself as king."This would be a very attractive option to RC based on what we know of his character. As I mentioned in an earlier post, though, the power relationships would start to get complicated very quickly, and it would be extremely challenging to maintain his authority over the others once they were established and he was not the sole source of resources.

I thought about a similar but slightly different question, though. Does he feel a pull to remain on the island, is he "institutionalized" in the way that a long-term prisoner or "naturalized" like a long-term immigrant might be? Is he tempted to let the ship return without him so that he can continue his life of solitude and reflection?

The narrator has told us many times that the grass is not always greener on the other side and that things are never as bad as they could be. And yet when given the chance he leaves immediately, without a second thought.

Summary of (Chapter 28)

Summary of (Chapter 28)

When Robinson arrived in England, he located the English captain’s widow with whom he had left his money back in his trading days. She had remarried and was now a widow again; she was in debt and so could not return Robinson’s money. In gratitude for her earlier kindness to him, he both absorbed his own loss and paid what he could of her debts.

He then returned to his former home in Yorkshire, but he found that his father, mother, and all but two sisters and two of his brother’s children remained alive. After so many years, they had given up Robinson for dead, and so there was nothing left of what would have been his inheritance.

Although his investments and inheritance were lost, Robinson was rewarded nearly two hundred pounds for his role in rescuing the ship and cargo from the mutineers. This, though, would not go far “towards settling me in the World,” so Robinson decided to go to Portugal to inquire about the plantation he owned in Brazil and whether his partner was still alive.

In Lisbon, Robinson met up with his former friend, the captain of the ship which had rescued Robinson in Africa after his escape from slavery. The captain informed Robinson that his partner had been alive the last time he had been in Brazil, nine years before. The trustees, however, had died, and Robinson’s share of profits from the plantation had been appropriated by the government beginning after twelve years; one-third of the proceeds were earmarked for the King, while two-thirds were donated to a monastery “to be expended for the Benefit of the Poor, and for the Conversion of the Indians to the Catholick Faith.” Because Robinson had returned alive, he had claim to some of the money.

The captain also told Robinson that he believed that the plantation was successful and that his partner had become rich. He assured Robinson that his legal claims to the plantation were strong and that the relatives of the dead trustees were honest and wealthy people who give Robinson a clear account of his profits over the years.

Robinson was troubled by the fact that part of his fortune had been left with the relatives of the trustees rather than being given to the captain as Robinson had specified in his will. The captain explained that there was no proof of Robinson’s death, and so it complicated the captain's claim to the inheritance. Moreover, improvements to the plantation such as building a sugar house and buying slaves had eaten into the proceeds during the first several years. Not only that, but the captain had been shipwrecked himself eleven years before and had had to use Robinson’s money to cover his losses. He gave Robinson what money he could along with his share of ownership in his son’s ship and a promise that Robinson would receive what he was due when his son returned.

Robinson was so moved by the captain’s honesty and kindness that he refused the old man’s gifts and instead wrote him a receipt for some of the money the captain had given him and took it as a loan.

Although Robinson had planned to go from there to Brazil to see to the plantation in person, the captain assisted with the legal process to declare himself living and to make a claim on the plantation without having to leave Portugal. About seven months after sending the documents to Brazil, Robinson received an account of the proceeds of the plantation that were owed him from the first ten years as well as a refund of some of the money that had been donated to the monastery. The King of Portugal, however, returned none of Robinson’s money.

Along with the financial documents, Robinson received a warm letter from his partner that described how the plantation had been improved during Robinson’s absence. He urged Robinson to come to Brazil himself and also included gifts of leopard skins, preserved fruit, and some gold coins. In the same ship, his received large quantities of sugar, tobacco, and money that was owed him by his trustees.

The narrator compares the course of Robinson’s fortunes to that of Job and comments that “the latter End of Job was better than the Beginning.” He found himself so astonished by his new wealth that he actually became ill and needed to be bled.

After he recovered, he continued to marvel at his riches, and he told the captain that, “next to the Providence of Heaven,” Robinson’s success was all because of him. He discharged any debts that the captain owed him and also created a pension fund for him and for his son after him.

Robinson’s life was now more complicated than his life had been on the island, where he “wanted nothing but what I had, and had nothing but what I wanted.” He needed to decide what course to take next to keep his fortune secure. He thought first of sending it to the widow, but since she was quite old and might be in debt, he considered bringing it to England himself. He was at a loss, though, to think of a trustworthy person with whom to leave his effects once he arrived there. In the meantime, Robinson sent money both to the widow and to his two living sisters.

Another choice was whether, after he did manage to deposit his fortune safely in England, Robinson should settle in Brazil permanently. The narrator explains that Robinson “was, as it were, naturaliz’d to the Place; but I had some little Scruple in my Mind about Religion.” While in Brazil originally, Robinson had not hesitated to proclaim himself a “Papist,” but now he regretted it and thought “it might not be the best Religion to die with.”

Job 42

Job 42

Robinson compares himself to Job when he writes that "the latter End of Job was better than the Beginning." This is a reference to Job 42 : 12. In previous chapters, God is describing his omniscience and omnipotence, and Job 42, the very last chapter of the book, begins with Job's reply.

Verses 7-9 are related to Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, three friends of Job who attempted to comfort him during his ordeal. Eliphaz has "not spoken the truth about" God in that he told Job that his misfortunes must have been the result of sin and that he should confess his secret sins to be relieved.

God is all-powerful and all-knowing, and his ways are unknowable, as Job has just expressed. His actions can't be explained in such a simplistic way, and Eliphaz and his friends should have the humility that Job has achieved through his ordeal.

42 Then Job replied to the Lord:

2 “I know that you can do all things;

no purpose of yours can be thwarted.

3 You asked, ‘Who is this that obscures my plans without knowledge?’

Surely I spoke of things I did not understand,

things too wonderful for me to know.

4 “You said, ‘Listen now, and I will speak;

I will question you,

and you shall answer me.’

5 My ears had heard of you

but now my eyes have seen you.

6 Therefore I despise myself

and repent in dust and ashes.”

Epilogue

7 After the Lord had said these things to Job, he said to Eliphaz the Temanite, “I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken the truth about me, as my servant Job has. 8 So now take seven bulls and seven rams and go to my servant Job and sacrifice a burnt offering for yourselves. My servant Job will pray for you, and I will accept his prayer and not deal with you according to your folly. You have not spoken the truth about me, as my servant Job has.” 9 So Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite did what the Lord told them; and the Lord accepted Job’s prayer.

10 After Job had prayed for his friends, the Lord restored his fortunes and gave him twice as much as he had before. 11 All his brothers and sisters and everyone who had known him before came and ate with him in his house. They comforted and consoled him over all the trouble the Lord had brought on him, and each one gave him a piece of silver and a gold ring.

12 The Lord blessed the latter part of Job’s life more than the former part. He had fourteen thousand sheep, six thousand camels, a thousand yoke of oxen and a thousand donkeys. 13 And he also had seven sons and three daughters. 14 The first daughter he named Jemimah, the second Keziah and the third Keren-Happuch. 15 Nowhere in all the land were there found women as beautiful as Job’s daughters, and their father granted them an inheritance along with their brothers.

16 After this, Job lived a hundred and forty years; he saw his children and their children to the fourth generation. 17 And so Job died, an old man and full of years.

Summary of (Chapter 29)

Summary of (Chapter 29)

Before leaving Portugal, Robinson answered the correspondence he had received from Brazil. He refused the offer from the monastery to return funds to him but instead donated them to the monastery and the poor. He sent a letter of thanks to the trustees and also contacted his partner to give him directions for managing Robinson’s share of the plantation. He sent gifts as well and informed his partner that he eventually planned to return to Brazil and settle there.

Once his affairs were in order, Robinson was perplexed about how he should travel from Portugal to England. For unknown reasons, he “had a strange Aversion to going to England by Sea at that time,” to the extent that he actually booked passage twice without boarding the ship in the end. Since it happened that one of those ships was captured by pirates and the other sank, the narrator credits his survival with heeding the “strong Impulses of his own Thoughts.”

In the end, Robinson decided to travel overland as far as Calais, from where he could cross the English Channel to Dover. With the help of the Captain, a traveling party was organized that included Robinson, Friday, three English merchants, and two Portuguese gentlemen.

On their approach to the Pyrenees Mountains, the uncertain weather and particularly the cold affected Robinson and Friday strongly. Snowstorms had halted them for nearly three weeks in Pamplona when they met a group of men who had used a guide to travel over the mountains from the French side. They reported that the snow conditions were amenable for travel, so Robinson engaged the same guide to lead his group over the mountains.

The guide led the men on a meandering course that avoided most of the snowy parts of the mountains. One afternoon, the guide was ahead of the main group when he and his horse were attacked by a pair of wolves and a bear. Friday, seeing the danger, rode to his assistance and shot one of the wolves in the head as the other fled from its attack on the horse. The Guide was not killed but was seriously injured, having received one bite on the arm and one on the upper leg.

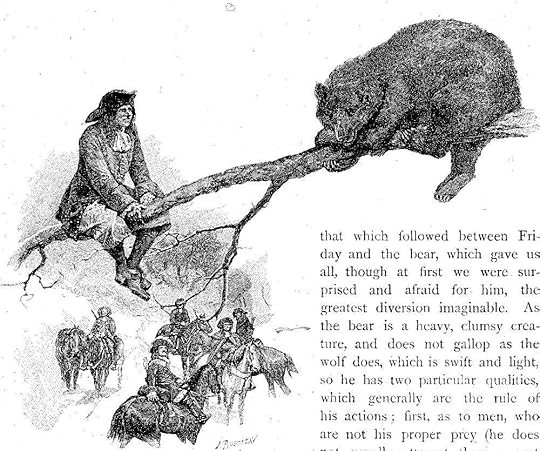

Next, Friday took on the bear. The narrator explains that a bear, although it does not generally target humans, is insulted easily and will never stop until it has gotten revenge. When Friday saw the bear, it was difficult for him to contain his excitement as he exclaimed that “Me shakee te Hand with him” and “Me eatee him up.” Friday threw a stone to attract the bear, and when the bear began to pursue him Friday led it back to where the men were.

There, Friday quickly climbed a tree and got as far out on a limb as possible. Each time the bear tried to walk out on the limb, Friday shook the limb and the bear retreated. The men laughed heartily at the site. Then Friday moved to the end of the limb so that it bent to the ground, where he jumped off and retrieved his gun.

The bear, realizing the Friday was on the ground, lowered himself little by little down the trunk of the tree. Before he reached the ground, Friday shot him dead. Friday explained to the amused men that his people hunted bears in this way with bows and arrows in his country.

However, the injured guide and the howls of more wolves in the area convinced the men to leave off Friday’s entertainment and continue on to their destination without bothering to skin the bear.

There are not bears in the Caribbean so how could Friday and his people have hunted bears with bows and arrows? The author seems to be using this incident with the wolves and the bear to make the story more exciting, and portray Friday as a hero.

There are not bears in the Caribbean so how could Friday and his people have hunted bears with bows and arrows? The author seems to be using this incident with the wolves and the bear to make the story more exciting, and portray Friday as a hero.

I agree with Connie. This section didn't ring true and seemed to be added for a taste of adventure and excitement.

I agree with Connie. This section didn't ring true and seemed to be added for a taste of adventure and excitement. Robinson seems to be a kind and generous man. He's given a lot of money away so as not to put others in distress.

I wondered at Robinson's sudden aversion to sea travel, especially when both times the ship's journeys ended in disaster. This aversion didn't happen in Robinson's earlier days. It seems that his experienced, or conversion, gave him some intuitive insight.

Chapter 28 has such a quantity of very precise and rather boring financial details, that again I wonder at how little was said about the probable future of the Spaniards and Friday's father.

Chapter 28 has such a quantity of very precise and rather boring financial details, that again I wonder at how little was said about the probable future of the Spaniards and Friday's father.Chapter 29, for me, is mostly about disgusting cruelty to animals. When Sam wondered at the editors' leaving these chapters out, I suspected something of the kind.

I laughed at the description of Madrid, though, along the lines of: we really wanted to see Madrid! But it was the end of summer, so we had to get away fast. This is summer in the Spanish city, baby %)

Connie: "There are not bears in the Caribbean so how could Friday and his people have hunted bears with bows and arrows? The author seems to be using this incident with the wolves and the bear to make the story more exciting, and portray Friday as a hero."

Connie: "There are not bears in the Caribbean so how could Friday and his people have hunted bears with bows and arrows? The author seems to be using this incident with the wolves and the bear to make the story more exciting, and portray Friday as a hero."Yes, things suddenly fall apart here. There is also the fact that three wolves and a bear attack as if they have arranged an ambush.

There are parallels between this episode and the scene in which RC kills a leopard after escaping from slavery. Here, though, Friday seems to me less a hero than a buffoon. Thinking back, this is the first time that we have actually heard him speak, and his broken pidgin English along with his antics make him seem like a (low) comic rather than heroic character.

Petra: "It seems that his experienced, or conversion, gave him some intuitive insight."

Petra: "It seems that his experienced, or conversion, gave him some intuitive insight."RC discusses the importance of listening to the inner voice of Providence earlier. He also pays attention to that when, after noticing the British ship off the coast of his island, he does not hail it immediately. Instead, he observes from a hiding place and sees that some of the men in the boats that have come ashore are prisoners.

He also seems to have good fortune regarding the people who befriend him. He is able to entrust his money to the English captain's widow, the Portuguese captain who rescues him from Africa gives him advice and looks after his affairs, and he has an honest partner in Brazil. He's never really been steered wrong except by the other planters in Brazil who encouraged him to voyage for slaves.

I agree with these comments about the scene with the bear and wolves. Pretty far-fetched.

I agree with these comments about the scene with the bear and wolves. Pretty far-fetched.I was impressed with the RC's generosity and actions to give what he deemed people were due or needed, instead of keeping all of his wealth for himself.

He seems to have adjusted to life back in civilization pretty easily. There is no mention of any changes in England that may have occurred in those 35 years since he left. I think most people require more time to adjust to a life so different form the one he had been living for the past 28 years on the island, most in isolation from other people.

Plateresca: "Chapter 28 has such a quantity of very precise and rather boring financial details, that again I wonder at how little was said about the probable future of the Spaniards and Friday's father."

Plateresca: "Chapter 28 has such a quantity of very precise and rather boring financial details, that again I wonder at how little was said about the probable future of the Spaniards and Friday's father."It seems like RC has moved on entirely. And since the rescue, we have heard very little of Friday himself until he showed himself to be a daredevil.

"I laughed at the description of Madrid, though, along the lines of: we really wanted to see Madrid! But it was the end of summer, so we had to get away fast. This is summer in the Spanish city, baby %)"

That struck me too! I first read it as wanting to leave because it was hot in Madrid, but that didn't really make sense because it was the end of summer and so should be cooling. But now when I read, I think what RC means (but doesn't explain clearly) is that they needed to hurry because they didn't want the roads from Pamplona over the Pyrenees to be impassable. The distance from Madrid to Pamplona is 250-300 miles (400-480 km), and they might do between 20 and 30 miles a day. They left Madrid in mid-October and then finally left Pamplona in mid-November.

It must have been culture shock for Friday to live in western Europe after living on an island, and Robinson (or Defoe) does not mention anything about his reaction. It makes RC seem very self-centered after all the help he received from Friday. The omission explains why there are so many authors that are writing sequels from Friday's point of view.

It must have been culture shock for Friday to live in western Europe after living on an island, and Robinson (or Defoe) does not mention anything about his reaction. It makes RC seem very self-centered after all the help he received from Friday. The omission explains why there are so many authors that are writing sequels from Friday's point of view.The howling wolves are bringing back memories of reading "Dracula" with the howling wolves in the Carpathian Mountains in Transylvania. "Robinson Crusoe" was published in 1719, but "Dracula" was published much later in 1897>

Summary of (Chapter 30)

Summary of (Chapter 30)

The party continued on over snowy ground toward a village, on a route that led through an open area surrounded by woods infested with wolves where their guide feared an attack. First, they saw several wolves run past without taking notice of the men, and further on they came upon around a dozen wolves feeding on the remains of a horse they had killed. Robinson forbade Friday to attack the wolves since he anticipated even more trouble ahead. Sure enough, as the group moved forward, the woods on their left echoed with howls and the men saw “about a hundred coming on directly towards us, all in a Body, and most of them in a Line, as regularly as an Army drawn up by experienc’d Officers.”

The men formed a line as if for battle, and Robinson instructed half of the men to send a first volley of fire that would be followed by a second volley from the other men. After the first volley, the advancing wolves stopped, terrified by the noise. Four of the leading wolves lay dead and several were injured.

The wolves withdrew but did not leave. Remembering that “the fiercest Creatures were terrify’d at the Voice of a Man,” Robinson and the other men shouted and screamed. When the wolves turned to retreat, the men fired their second volley, and the wolves disappeared into the woods.

As the daylight began to fade and the men continued forward across the open area, they found themselves surrounded by two or three packs of wolves. The men advanced toward a gap in the woods, which they soon perceived was blocked by another huge group of wolves.

From another gap in the woods, the men heard the sound of a gun and then saw a horse emerge from the woods at a gallop, pursued by more than a dozen wolves. When they approached the entrance, the men saw that the wolves had killed the man who had fired the gun along with another man and his horse.

What might have been three hundred wolves approached the men from the other side of the open area. Before the animals could attack, the men positioned themselves behind some downed trees, with their horses protected behind them, and prepared to fire. The wolves rushed the men’s position, and even though several were killed by the first volley from the men’ guns, the wolves continued to push forward. With each charge of the wolves, the men fired a volley from one of their firearms until they had discharged nearly all of them.

Thinking fast, Robinson ordered one of his servants to pour a line of gunpowder along the top of their defenses. This done, Robinson lit the powder as the wolves passed the barrier and set several of the wolves on fire. The others, wary of the fire, pulled back.

With a volley from the remaining charged firearms and a shout, the men drove the remaining wolves away. Many wolves lay injured at the scene of the battle, and the men “sally’d immediately upon near twenty lame Ones, who we found struggling on the Ground, and fell a cutting them with our Swords, which answer’d our Expectation; for the Crying and Howling they made, was better understood by their Fellows so that they all fled and left us.” Altogether, the men killed about sixty wolves.

When the men finally arrived at their destination, the people in the village shared the harrowing story of constant attacks by wolves and bears who wanted to kill both cattle and people. There, the guide took a turn for the worse, so the group left him there and moved on with a different guide to Toulouse, in southern France.

In Toulouse, the people were shocked to hear that the guide had brought them through an area where they would be sure to be attacked by wild creatures. They also blamed the men for dismounting and protecting their horses behind them since in that way they had put themselves between the wolves and their prey. They could have instead remained mounted since the wolves would not have recognized the horses; alternatively, they could have abandoned their horses to the wolves and escaped while the wolves were distracted.

The narrator comments that “I shall never care to cross those Mountains again; I think I would much rather go a thousand Leagues by Sea, though I were sure to meet with a Storm once a Week.”

Finally, after traveling through France via Paris to Calais, Robinson took passage across the English Channel and arrived at last in England, two months after leaving Pamplona.

After arranging his affairs with the English captain’s widow, Robinson turned his attention to his next steps. He planned to return to Lisbon and go from there to Brazil, but then he considered his “Doubts about the Roman Religion” and the fact that, to live in Brazil he must either “embrace the Roman Catholick Religion” or “be a Martyr for Religion, and die in the Inquisition.” Faced with these choices, Robinson decided to sell his share of the plantation and remain in England.

The Lisbon captain arranged for Robinson to sell his estate to the two men who had been acting as his trustees. As part of the financial arrangements, Robinson funded the pension program for his friend and his son.

Even though Robinson might be expected to retire quietly after all of his adventures, he found that he “was inur’d to a wandering life” and felt drawn both to Brazil and to “my Island.” In particular, Robinson was curious to know whether the Spaniards had arrived and whether the mutineers had treated them well.

The widow dissuaded Robinson from leaving for the next seven years, and during that time he supported his two nephews, raising one to be a gentleman and the other to be a ship’s captain. He also married and had two sons and a daughter of his own.

After he was widowed and his nephew had become a successful captain, Robinson left again for more adventures as a trader to the East Indies. On the trip “I visited my new Collony in the Island” and learned that, while at first the three mutineers had dominated the Spaniards, they were eventually overthrown. There had been several “Battles with the Carribeans,” and the new colonists had improved the island in several ways. They had also managed to free eleven men and five women from captivity, and among them all there were now twenty children.

Robinson gave the colonists additional supplies and, while maintaining ownership of the island itself, divided it between the colonists for their use. From Brazil, Robinson sent seven women who would be wives for some of the Spaniards, and he promised the English colonists to send some women from England as well if they agreed to contribute to the colony. He also sent livestock to the settlers.

The narrator hints that he will follow his account with additional adventures involving attacks by Caribs and “some very surprising Incidents in some new Adventures of my own” that occurred over the next ten years.

And that brings us to the end of the text! I will have illustrations to share once I have them formatted.

And that brings us to the end of the text! I will have illustrations to share once I have them formatted.I'm looking forward to your comments about this last section as well as final comments for the book as a whole!

We've had several interesting topics in our discussions that I am pondering. What do I like about the book and what do I dislike? What exactly is the author's purpose, and how is that reflected in the text? How much should historical/cultural/religious context inform my response to a work like this?

I had to finish the novel a little early because of an expiring loan so I have waited on further comments for the end. I agree that Defoe had some issues figuring out how to end the novel, but they are in accord with issues Defoe has had from the beginning. There is also a difficulty of judging the novel that stems from choosing what perspective from which are we are to judge. If we are to look at the novel as a reader of the period might, I feel it is very effective though I think we should consider the aspects of the novel that are meant to influence, teach and persuade with caution, since they to me sound like U.S. Navy enlistment commercials--"Join the Navy and See the World!" where a few details of the reality are left out. The reader of today will find more to fault but I don't support ignoring the novel because of its faults.

I had to finish the novel a little early because of an expiring loan so I have waited on further comments for the end. I agree that Defoe had some issues figuring out how to end the novel, but they are in accord with issues Defoe has had from the beginning. There is also a difficulty of judging the novel that stems from choosing what perspective from which are we are to judge. If we are to look at the novel as a reader of the period might, I feel it is very effective though I think we should consider the aspects of the novel that are meant to influence, teach and persuade with caution, since they to me sound like U.S. Navy enlistment commercials--"Join the Navy and See the World!" where a few details of the reality are left out. The reader of today will find more to fault but I don't support ignoring the novel because of its faults. It is my opinion we learn from reading such. I was surprised at how much we got caught up in the verisimilitude of the novel, discussing whether certain things were possible as if this were real. Defoe does the illusion of reality well, but along with his reality, Defoe is offering a life philosophy and blueprint for success. Crusoe is individualistic but to the point where he is extremely exaggerated with self. He seeks to control everything. He does not integrate; he dominates. This psychology while understandable for the period, is not so appealing today with environmental and sixth extinction concerns. History shows the potential dangers of a competitive rather than cooperative mindset. The drawbacks of a self-centered perspective seem undeniable. Yet I think this is where we connect to the novel. The novel feeds the fantasy of "a king and his castle," or "the world is your oyster." Perhaps when reading the novel we should be aware of that and indulge in some humility and empathy in contrast. The novel reminds me of The Autobiography of Ben Franklin. It is another book with which readers identify and it emphasizes a success with hard work story. I don't know if it is easier to root out the truth from fantasy in the latter but I feel the value in both books lies in our ability to do so.

Erich, first of all, thank you for the enormous work you've done on this book. Whatever I think about it, I would certainly have enjoyed and understood it less without your valuable insights.

Erich, first of all, thank you for the enormous work you've done on this book. Whatever I think about it, I would certainly have enjoyed and understood it less without your valuable insights.I am very interested in how all of you here feel about the book now!

I need some time to process my impressions, but right now... I think that Robinson as a character is often selfish and brutal (despite all his generosity in the end). I think people tend to preserve a huge amount of tenderness for characters they loved as children, so it's possible that something similar happened to Charles Dickens with Robinson, but Dickens being so sensitive to other people's suffering, I wonder if maybe he did, after all, understand this aspect of Robinson.

The part where Robinson was inventing ways to make things work for him on the island was hands-down my favourite one.

And, as it often happens in 'Dickensians!', though I defnitely did not enjoy each and every chapter, I enjoyed the discussion :)

Erich, first of all, I want to echo Plateresca's thanks for the great job you've done in leading this discussion and providing valuable background information for it. We appreciate you!

Erich, first of all, I want to echo Plateresca's thanks for the great job you've done in leading this discussion and providing valuable background information for it. We appreciate you!Usually, when I join in discussions of books I've already read and reviewed, I link to my own review once the other readers are finished with, or starting to finish, the read. But my review of this book was a retrospective one; I'd nominally read it twice in my pre-Goodreads days, once as a child and again in the 90s. By 2019, when I wrote the review, my memories weren't sharp; and moreover, today's discussion has revealed to me that I didn't read the same book. It turns out that what I read (at least, the second time, in the 90s) was a combination of this book and its sequel; but I didn't know that at the time. Most importantly, others' comments in the discussion have changed my perspective on some aspects of the book. So my review is too obsolete to share at this point. As soon as I can (hopefully sometime next year), I plan to reread the actual novel, and then rewrite the review to incorporate my current thoughts.

However, one thought I can share is that Defoe apparently was, like most city-dwellers then and now, fairly ignorant about both wolves and bears (neither of which are native to the Carribean islands). He did get one thing right, or close to right, in suggesting that the wolves were more interested in attacking the horses, which they thought of as prey, than the humans (who incurred the wolves' wrath by interposing, rather than being attacked as prey themselves). But wolves don't typically hunt in packs of hundreds, and bears and wolves don't hunt in close proximity to each other.

Thank you, Erich, for this wondeful discussion. I very much enjoyed your leading of this read and all the information you added. The pictures are wonderful, too. Thank you for all the effort you put gave to this read.

Thank you, Erich, for this wondeful discussion. I very much enjoyed your leading of this read and all the information you added. The pictures are wonderful, too. Thank you for all the effort you put gave to this read. I'm glad I read the book. It was different than I recalled from the story I read as a child.

As Plateresca mentioned, I also wondered why this would be one of Dickens' favorite reads. The character of Robinson seems unsympathetic to his characters. Robinson seems selfish and self-centered compared to Dickens' (at least the "good guys").

I enjoyed the parts at the beginning, where Robinson was a cocky young man, ready to face the World on his own terms. I continued to enjoy the unfolding of the story, until the rescue of Friday's father and the Spaniard. I found the story a bit less interesting after that.

The escape across the mountains was my least favorite part. It was too unbelievable and the scene with the bear was unnecessary. I suppose this section was added for adventure and excitement. Perhaps it worked in the time of Defoe.

Upon his return to Europe, he becomes kinder and generous to those of his past. It shows that Robinson does, at times, consider others, but that he has a dividing ling between those of his equal and those below him (in his eyes).

However, the return to Europe seemed flat because it's all about his movements. There's no thought or feeling about the hardships (or not) of returning to civilization, the changes that occurred in his absence, his relationship with his wife & children, etc. There's a lack of feeling and insight.

All in all, I'm glad I read this book and I loved this discussion. It gave me a broader, more interesting, insight into this book and, I'm sure, raised my enjoyment of reading it.

Illustrations for Chapters 28-30

Illustrations for Chapters 28-30Images and commentary via Victorian Web

Crusoe arrives at Lisbon

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: Having returned to England, Crusoe immediately sets out for Lisbon to visit the Portuguese sea-captain who picked him up three decades earlier off the African coast. Defoe's putting his protagonist onto the Continent and into a series of adventures at this late point in the narrative may strike modern novel-readers as somewhat anticlimactic. However, Defoe was essentially making up the conventions of the new prose narrative form on the fly, and was perhaps already thinking of a sequel.

Upon this he pulls out an old pouch

Wal Paget, 1891

Crusoe's Troop on the March

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: The image makes Crusoe look like one of the protagonists of Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers, and his cavalcade appear to be a formidable armed column descending from the heights of a town in the Pyrenees. The heavy cloaks which lend the riders a military air complement the late fall setting and the altitude, preparing us for the adventures of Crusoe and Friday in Langedoc and Gascony.

Two of the wolves flew upon the guide

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget has a strong sense of dramatic action and realism in his depiction of the animals; in particular, Paget's predators have luxuriant fur and well-muscled, lithe bodies that suggest he studied his subject. The wolves have attacked with such celerity that they have caught the guide unawares. Not having had time to draw the long-muzzled pistol in his holster, the rider withdraws his hand from the wolf's reach, even as he kicks him. The second wolf prepares to attack the mount. But Friday, pistol already drawn, is riding to the rescue from the snow-covered slope above, the few fir trees establishing the alpine setting. The third wolf which the narrator mentions is not in evidence, and the guide has yet to be bitten. The illustration prepares the reader both for further wolf attacks and for Friday's timely intervention.

Friday and the Bear out on a limb

George Cruikshank, 1831

Friday and the Bear

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863

Commentary: At this point, the bear is standing and attempting to maintain his balance but clearly poses Friday no real danger. The jaunty feather which Friday alone of all Crusoe’s party wears in his hat matches the litheness of his figure and the blitheness of his spirit.

Friday and the Bear out on a Limb

Phiz, 1864

"What, you come no farther?"

Wal Paget, 1891

Commentary: Paget’s Friday is more soberly dressed and, although smiling, is not the reckless practical joker that he was in the earlier illustrations. The five horsemen with Crusoe in their lead are enjoying a light-hearted moment rather than expressing apprehension.

Crusoe and his Comrades repelling a massive Wolf attack

George Cruikshank, 1831

Commentary: Cruikshank employs the clouds of gunpowder to compensate for a lack of background detail and suggest the sheer size of the volley that the travellers have unleashed upon the attacking wolves, who look rather much like Dobermans.

The Wolves driven off

Unknown artist, published in Cassell, 1863