Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Nicholas Nickleby

Nicholas Nickleby - Group Read 6

>

Nicholas Nickleby: Chapters 49 - 65

Bridget wrote: He barely mentions Madeline by name and yet the apprehension of her arrival is always in the reader's mind.

Bridget wrote: He barely mentions Madeline by name and yet the apprehension of her arrival is always in the reader's mind.Indeed! Good comments, Bridget. Imagining Madeline arriving here is really dreadful. Barely mentioning her by name shows that Gride considers her as a thing. I think he is one of the worst Dickens protagonists I have met this far.

Marvelous comments Jim and Bridget. I love the description of the clock, which I had marked when I was reading. I also noted that he was thrilled that the pawnbroker had left a shilling in the pocket of the coat he bought. He no doubt needed the shilling less than the pawnbroker did, but his real delight was in the fact that he had deprived someone else of it.

Marvelous comments Jim and Bridget. I love the description of the clock, which I had marked when I was reading. I also noted that he was thrilled that the pawnbroker had left a shilling in the pocket of the coat he bought. He no doubt needed the shilling less than the pawnbroker did, but his real delight was in the fact that he had deprived someone else of it.Bridget As I read them, always lingering in the back of my mind was the idea of Madeline coming to live there. I found myself thinking how she would not only have to contend with the horror of Gride, but she would be bullied and abused by Peg as well and find no rest or solace from either of them.

message 55:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 01, 2024 02:34AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Writing Style

Werner said “I share the feelings of those who have stated that Lord Frederick’s death is tragic, and fundamentally unfair (and, certainly, any reader who didn’t feel the same way would be heartless indeed!) Dickens is very conscious of the fact that we live in a world where life is very often tragic and unfair; and it’s part of his literary artistry that he takes that dimension seriously and reflects it realistically.

Portraits of life that are composed entirely of sweetness and light ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level. Dickens does convince, and that’s part of why his works endure.“

To be fair, I needed to quote the whole post, as I’m going to be tough here (but I know you can take it! 😊) The first part is obviously fine; it’s a personal reaction we all share. But the final two or three sentences are critical comment, and the last have problems 🤔 - which is why I separated them out.

“Portraits of life that are composed entirely of sweetness and light ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level.”

It sounds convincing enough, but an easy way to test this is to look at its opposite. There are two assertions. If we substitute “bitter and evil” for “sweetness and light”, we may also think there is some truth in it, viz. “Portraits of life that are composed entirely of bitter and evil ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level.” If we negate both parts we get “Portraits of life that are composed entirely of bitter and evil ultimately convince at a deeper level” which clearly you are not suggesting! So that original assertion is a bit shaky.

Perhaps what you mean is something more like “Portraits of life that are not very deeply observed from life, ultimately fail to convince”. This is standard critical thinking on Victorian novels - and indeed all good literature - but oddly does not work with Charles Dickens. (Perhaps it is one of the reasons he was not considered "great literature" in his own country in the late 20th century, and was not studied at my school or any I knew. But that's purely conjecture.) I'll try to explain why he's different.

You go on to say “Dickens does convince, and that’s part of why his works endure”

The two sentences together are predicated on your assessment of Charles Dickens as a realistic author.

Well in many ways he is, but not in the way that, for instance George Eliot is, or his contemporary Elizabeth Gaskell. If he was rooted in realism he would not include so many ghosts and spirits, or use metaphors such as the fairy or the goblin - and then base his whole description around the metaphor. So many descriptions are larger than life; extravagant or personified or all three. Charles Dickens indulges in flights of fancy. We saw a perfect example of this with the comic grotesques Arthur Gride and Peg Sliderskew, in the very next chapter.

Let’s take Wackford Squeers as an example of a “portrait of life”. He is certainly a character who has “endured”. In fact I would guess that out of all the characters in Nicholas Nickleby (excluding the eponymous one) it would be Squeers and his “Dotheboys Hall” whom readers remember - whether they have read the book, seen a film, or simply come across him in a comic or popular culture. Like many of Charles Dickens’s creations, such as Scrooge, Uriah Heep, Quilp, the Artful Dodger, Miss Havisham, Mr Pickwick, Little Nell, or Tiny Tim his fame has spread far and wide, and our public perception of each of these means that they have taken on an even more vivid life of their own.

Charles Dickens’s genius here, lies in the fact that he able to give a character or situation enough realism to convince us, but from then on he is free to indulge his fantasy. With Squeers, he has used factual accounts, but what he has created is grossly distorted into a comic grotesque. Squeers describes beatings with relish, his grandiose behaviour is comic, his mistakes with vocabulary and grammar are humorous. Everything about Squeers is over the top, and if if were not, he would not be such an entertaining figure. We would have to steel ourselves to read about him, because the reality of the events described is so awful.

But Charles Dickens makes free - some might say over-indulgent - use of additional tools, such as sarcasm and irony, which again have minimal place in a realistic account. With Charles Dickens we can read and enjoy believing in his world as we read, and also use our “reality filter” to see the facts which lie behind his caricatures and his words. We also see dreamlike elements where his belief in mesmerism informs his writing, so that a character sees something they cannot have, or is in two places, or a journey takes a longer or shorter time (it might even be an instant moment of consciousness) in Charles Dickens's world than it does in real life. We saw all this in Oliver Twist, and there are a few examples in each novel as well as being sprinkled through his other fiction. This is not a feature of a realistic novel.

So although you maintain Werner that it is partly because Charles Dickens writes realistic portraits that his work “endures”, and although this is often true of classic literature, there is evidence that with Charles Dickens it is precisely the opposite! “Endures” suggests what is memorable, and what we remember about his portraits are these grossly exaggerated, larger than life characters. The ones who popped into my mind from a variety of his fiction are not all ogres either; both Little Nell and Tiny Tim (and others) actually are all “sweetness and light”. And they do convince … enough to have me in tears anyway.

Charles Dickens has his own take on realism. He wants his novels to be persuasive - especially when they seek to improve social conditions. And because of this, he is scrupulously fair to his readers. He always provides endings for those we care about, according to their moral behaviour. We know that the villains are going to pay for their deeds, and that the heroes are going to have a good end. We are rarely if ever left wondering, and always satisfied with his justifiable and believable endings.

But along the way there are casualties and these are usually to be expected. They may be the “wise child” Victorian stereotype we are sure will be doomed, because that is their role in the story. They may be waifs and strays we see on the way, who represent victims of the bad social system and whom we never really get to know. They may be adults, ditto. If we learned on the way that Squib (Fanny Squeers’s maid) had died, or Mrs Wititterly, or Mr Folair (in the theatre troupe) or the Infant Phenomenon, or Mr Pyke or Mr Pluck had died, we would doubtless have believed what he described, but not have felt very moved either way. We are not as invested in those characters.

Here’s the crunch (and I’m sorry to took so long to get here, but this has enabled me to highlight an interesting aspect!) Lord Frederick Verisopht is one of these satirical characters, put in for the specific purpose of amusement and social satire, and whom we believe in but do not care much about. No, he is not all “sweetness and light”, but neither is he a fully rounded character. He’s a type, and initially described ironically.

When we first met Lord Frederick Verisopht, he was a youth who spoke in incomplete drawling upper-class tones, whining that his friend was monopolising pretty Miss Nickleby. Charles Dickens wrote him to satirise the upper-class twit; we have quite a few of these wealthy and brainless young men in his novels. Edmund Sparkler in Little Dorrit is another. Charles Dickens may well have intended him to try to woo Kate, as Paul suggested, but ultimately ineffectually, because Kate is nowhere near as ambitious and self-serving as (view spoiler).

However, on the last two occasions we saw him, Lord Frederick had undergone a complete transformation. He was looking after his friend, and warned him (remarkably enough in standard English) that he would not stand for an attack on Nicholas. Hawk and Ralph think he is still “green”, but we are beginning to wonder.

The masterly last chapter of his story show a completely different person. Gone is the drawling, sulky and peevish manner. This Lord Verisopht is noble, principled and courageous. The original illustrator Hablot Knight Browne had terrible difficulty being consistent, and if you look at his first etching and compare it with the brawl in the gaming room, these are of two completely different men; the last by his build and face a good ten years or more older than the first.

Charles Dickens always gave instructions (or at least approved) these illustrations, but he did not complain for the simple reason that he had changed his mind about the character. In this installment we read an articulate but agonised man’s thoughts; his numbness knowing he is likely doomed, and his final vague regrets about his life. It is a magnificent piece of writing, and convinces us completely. We care - and care a lot! This is no longer about a comic, satirical character.

Charles Dickens cheated - and he knew it. He had broken his own rule. The proof lies in the change of his name. It is no longer an apt descriptive name such as “Very - soft” or a “Hawk”, “Pyke”, or “Pluck”, but “Lord Frederick”. As I said earlier, Charles Dickens changed all reference to the name “Verisopht” in his book editions, save the first couple, which he could not alter while remaining consistent with the serial.

We are used to being manipulated by an author, but Lord Frederick Verisopht is not a character whom Charles Dickens has built up and represented realistically. Nobody changes so much in less than a year. But it enabled Charles Dickens to remove the threat of Hawk at a crucial point (as Kelly pointed out). Nicholas's enemy is now concentrated and focussed in Ralph Nickleby, which is much better dramatically.

I'm afraid Lord Frederick Verisopht is not at all a good example of Charles Dickens "literary artistry" - nor is he one who endures (except perhaps for a few of us). Sir Mulberry Hawk, on the other hand, does. He has stayed in character throughout so far. 😡 Few who remember the novel will forget Sir Mulberry Hawk. Plus, as so often with Charles Dickens, Hawk is an extreme, which as we've established by all popular definitions of “good writing”, should not work!

Our personal reactions of grief for Lord Frederick have been contrived at the last minute by Charles Dickens. Lord Frederick Verisopht is not a great tragic figure who embodies the depth of character we expect in a classic novel. Not many of these characters are! We remember them because of their quirks and great entertainment value, by which Charles Dickens cleverly sometimes also enables us to remember the serious themes.

Werner said “I share the feelings of those who have stated that Lord Frederick’s death is tragic, and fundamentally unfair (and, certainly, any reader who didn’t feel the same way would be heartless indeed!) Dickens is very conscious of the fact that we live in a world where life is very often tragic and unfair; and it’s part of his literary artistry that he takes that dimension seriously and reflects it realistically.

Portraits of life that are composed entirely of sweetness and light ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level. Dickens does convince, and that’s part of why his works endure.“

To be fair, I needed to quote the whole post, as I’m going to be tough here (but I know you can take it! 😊) The first part is obviously fine; it’s a personal reaction we all share. But the final two or three sentences are critical comment, and the last have problems 🤔 - which is why I separated them out.

“Portraits of life that are composed entirely of sweetness and light ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level.”

It sounds convincing enough, but an easy way to test this is to look at its opposite. There are two assertions. If we substitute “bitter and evil” for “sweetness and light”, we may also think there is some truth in it, viz. “Portraits of life that are composed entirely of bitter and evil ultimately fail to convince at a deeper level.” If we negate both parts we get “Portraits of life that are composed entirely of bitter and evil ultimately convince at a deeper level” which clearly you are not suggesting! So that original assertion is a bit shaky.

Perhaps what you mean is something more like “Portraits of life that are not very deeply observed from life, ultimately fail to convince”. This is standard critical thinking on Victorian novels - and indeed all good literature - but oddly does not work with Charles Dickens. (Perhaps it is one of the reasons he was not considered "great literature" in his own country in the late 20th century, and was not studied at my school or any I knew. But that's purely conjecture.) I'll try to explain why he's different.

You go on to say “Dickens does convince, and that’s part of why his works endure”

The two sentences together are predicated on your assessment of Charles Dickens as a realistic author.

Well in many ways he is, but not in the way that, for instance George Eliot is, or his contemporary Elizabeth Gaskell. If he was rooted in realism he would not include so many ghosts and spirits, or use metaphors such as the fairy or the goblin - and then base his whole description around the metaphor. So many descriptions are larger than life; extravagant or personified or all three. Charles Dickens indulges in flights of fancy. We saw a perfect example of this with the comic grotesques Arthur Gride and Peg Sliderskew, in the very next chapter.

Let’s take Wackford Squeers as an example of a “portrait of life”. He is certainly a character who has “endured”. In fact I would guess that out of all the characters in Nicholas Nickleby (excluding the eponymous one) it would be Squeers and his “Dotheboys Hall” whom readers remember - whether they have read the book, seen a film, or simply come across him in a comic or popular culture. Like many of Charles Dickens’s creations, such as Scrooge, Uriah Heep, Quilp, the Artful Dodger, Miss Havisham, Mr Pickwick, Little Nell, or Tiny Tim his fame has spread far and wide, and our public perception of each of these means that they have taken on an even more vivid life of their own.

Charles Dickens’s genius here, lies in the fact that he able to give a character or situation enough realism to convince us, but from then on he is free to indulge his fantasy. With Squeers, he has used factual accounts, but what he has created is grossly distorted into a comic grotesque. Squeers describes beatings with relish, his grandiose behaviour is comic, his mistakes with vocabulary and grammar are humorous. Everything about Squeers is over the top, and if if were not, he would not be such an entertaining figure. We would have to steel ourselves to read about him, because the reality of the events described is so awful.

But Charles Dickens makes free - some might say over-indulgent - use of additional tools, such as sarcasm and irony, which again have minimal place in a realistic account. With Charles Dickens we can read and enjoy believing in his world as we read, and also use our “reality filter” to see the facts which lie behind his caricatures and his words. We also see dreamlike elements where his belief in mesmerism informs his writing, so that a character sees something they cannot have, or is in two places, or a journey takes a longer or shorter time (it might even be an instant moment of consciousness) in Charles Dickens's world than it does in real life. We saw all this in Oliver Twist, and there are a few examples in each novel as well as being sprinkled through his other fiction. This is not a feature of a realistic novel.

So although you maintain Werner that it is partly because Charles Dickens writes realistic portraits that his work “endures”, and although this is often true of classic literature, there is evidence that with Charles Dickens it is precisely the opposite! “Endures” suggests what is memorable, and what we remember about his portraits are these grossly exaggerated, larger than life characters. The ones who popped into my mind from a variety of his fiction are not all ogres either; both Little Nell and Tiny Tim (and others) actually are all “sweetness and light”. And they do convince … enough to have me in tears anyway.

Charles Dickens has his own take on realism. He wants his novels to be persuasive - especially when they seek to improve social conditions. And because of this, he is scrupulously fair to his readers. He always provides endings for those we care about, according to their moral behaviour. We know that the villains are going to pay for their deeds, and that the heroes are going to have a good end. We are rarely if ever left wondering, and always satisfied with his justifiable and believable endings.

But along the way there are casualties and these are usually to be expected. They may be the “wise child” Victorian stereotype we are sure will be doomed, because that is their role in the story. They may be waifs and strays we see on the way, who represent victims of the bad social system and whom we never really get to know. They may be adults, ditto. If we learned on the way that Squib (Fanny Squeers’s maid) had died, or Mrs Wititterly, or Mr Folair (in the theatre troupe) or the Infant Phenomenon, or Mr Pyke or Mr Pluck had died, we would doubtless have believed what he described, but not have felt very moved either way. We are not as invested in those characters.

Here’s the crunch (and I’m sorry to took so long to get here, but this has enabled me to highlight an interesting aspect!) Lord Frederick Verisopht is one of these satirical characters, put in for the specific purpose of amusement and social satire, and whom we believe in but do not care much about. No, he is not all “sweetness and light”, but neither is he a fully rounded character. He’s a type, and initially described ironically.

When we first met Lord Frederick Verisopht, he was a youth who spoke in incomplete drawling upper-class tones, whining that his friend was monopolising pretty Miss Nickleby. Charles Dickens wrote him to satirise the upper-class twit; we have quite a few of these wealthy and brainless young men in his novels. Edmund Sparkler in Little Dorrit is another. Charles Dickens may well have intended him to try to woo Kate, as Paul suggested, but ultimately ineffectually, because Kate is nowhere near as ambitious and self-serving as (view spoiler).

However, on the last two occasions we saw him, Lord Frederick had undergone a complete transformation. He was looking after his friend, and warned him (remarkably enough in standard English) that he would not stand for an attack on Nicholas. Hawk and Ralph think he is still “green”, but we are beginning to wonder.

The masterly last chapter of his story show a completely different person. Gone is the drawling, sulky and peevish manner. This Lord Verisopht is noble, principled and courageous. The original illustrator Hablot Knight Browne had terrible difficulty being consistent, and if you look at his first etching and compare it with the brawl in the gaming room, these are of two completely different men; the last by his build and face a good ten years or more older than the first.

Charles Dickens always gave instructions (or at least approved) these illustrations, but he did not complain for the simple reason that he had changed his mind about the character. In this installment we read an articulate but agonised man’s thoughts; his numbness knowing he is likely doomed, and his final vague regrets about his life. It is a magnificent piece of writing, and convinces us completely. We care - and care a lot! This is no longer about a comic, satirical character.

Charles Dickens cheated - and he knew it. He had broken his own rule. The proof lies in the change of his name. It is no longer an apt descriptive name such as “Very - soft” or a “Hawk”, “Pyke”, or “Pluck”, but “Lord Frederick”. As I said earlier, Charles Dickens changed all reference to the name “Verisopht” in his book editions, save the first couple, which he could not alter while remaining consistent with the serial.

We are used to being manipulated by an author, but Lord Frederick Verisopht is not a character whom Charles Dickens has built up and represented realistically. Nobody changes so much in less than a year. But it enabled Charles Dickens to remove the threat of Hawk at a crucial point (as Kelly pointed out). Nicholas's enemy is now concentrated and focussed in Ralph Nickleby, which is much better dramatically.

I'm afraid Lord Frederick Verisopht is not at all a good example of Charles Dickens "literary artistry" - nor is he one who endures (except perhaps for a few of us). Sir Mulberry Hawk, on the other hand, does. He has stayed in character throughout so far. 😡 Few who remember the novel will forget Sir Mulberry Hawk. Plus, as so often with Charles Dickens, Hawk is an extreme, which as we've established by all popular definitions of “good writing”, should not work!

Our personal reactions of grief for Lord Frederick have been contrived at the last minute by Charles Dickens. Lord Frederick Verisopht is not a great tragic figure who embodies the depth of character we expect in a classic novel. Not many of these characters are! We remember them because of their quirks and great entertainment value, by which Charles Dickens cleverly sometimes also enables us to remember the serious themes.

It seems to me that in writing this this novel in serial installments that he published as they were written, not knowing completely how the story will turn out, Dickens took a significant risk of writing himself into a dilemma. Despite all of his skill, the transformation of Lord Frederick’s character is still a bit of a stretch. I’m struck by how vastly different his approach was later on, when he wrote Dombey and Son, which he meticulously planned out in advance. Dickens himself seems to have “changed his spots” as a writer over the years.

It seems to me that in writing this this novel in serial installments that he published as they were written, not knowing completely how the story will turn out, Dickens took a significant risk of writing himself into a dilemma. Despite all of his skill, the transformation of Lord Frederick’s character is still a bit of a stretch. I’m struck by how vastly different his approach was later on, when he wrote Dombey and Son, which he meticulously planned out in advance. Dickens himself seems to have “changed his spots” as a writer over the years.

Jean, you've shared, as usual, very substantial, well-articulated and constructive thoughts (and for the most part I don't actually disagree with what you wrote, as such). You've made me realize, though, that I should clarify what I wrote earlier, to avoid misunderstandings.

Jean, you've shared, as usual, very substantial, well-articulated and constructive thoughts (and for the most part I don't actually disagree with what you wrote, as such). You've made me realize, though, that I should clarify what I wrote earlier, to avoid misunderstandings.As you realized, I wasn't suggesting that portraits of life composed just of bitterness and evil are the only truly convincing ones. IMO, the most convincing novels are those which recognize both the good and bad aspects of the world as it is. (In my original comment, I concentrated on the insufficiency of only the former because, at that point, it was Dickens' inclusion of a strong dose of the latter that was causing us all some vicarious sorrow.)

Jean wrote: "Charles Dickens has his own take on realism."

He does indeed; and while I would stand on the contention that his writing is "realistic" in a basic sense, I would never classify him as a Realist. He seems to me to be basically a Romantic writer (though he's not a stereotypically true-to-type representative of that school either --his humor diverges from the dead-serious Romantic model). He's mainly aiming at evocation of emotion from the reader rather than reproducing the world with photographic realism, so if for instance exaggeration and caricature will serve the former end, photographic realism can go bye-bye. Even in exaggeration and caricature, though, he starts with pretty shrewd observation of reality as it is, and roots his characterizations in it. His novels show us our world writ larger than life -but it's still recognizably our world.

I've said elsewhere that the characters here are not dynamic, in a moral sense; but Lord Frederick comes the closest to being a dynamic character. I don't think he changes his theoretical ideals at any point; but he certainly does get his eyes opened to how much Hawk and Co. have been diverging from those ideals, and acts on that new awareness at great cost to himself. Whether we see that kind of change as "realistic" or not depends on how we view human moral possibilities in the real world; and whether we see that sort of dynamism in a character as a serious literary flaw or a mark of authorial genius (or, maybe, as something in between) depends on our views about literature.

The last two posts by Jean and Jim are excellent, worth rereading, and extremely thought-provoking for me because they delve a bit deeper into the art of writing, more specifically, Dickens art of writing. Jean and Jim are more well read and have far more experience in defining Dickens as an author than I. I would suggest their picture of Dickens is much more complete because of that experience.

The last two posts by Jean and Jim are excellent, worth rereading, and extremely thought-provoking for me because they delve a bit deeper into the art of writing, more specifically, Dickens art of writing. Jean and Jim are more well read and have far more experience in defining Dickens as an author than I. I would suggest their picture of Dickens is much more complete because of that experience.In contrast, my picture of Dickens is far from complete. When I look at what the author is doing, I do not see a static formed author behind the work, but rather a collection of possibilities. So for example, as Jim makes his points about Dickens' serial writing at the time of writing Nicholas Nickleby, I have various threads of thought about what goals Dickens may have been pursuing when writing such and such a thing. Two separate threads might be whether Dickens was writing with an eye to the whole of the serial run or with an eye to the episode of the moment. Each thread creates a different picture of the author in my mind. Basing my thoughts on all the serial material I have read of Dickens, plus that of other authors in literature, as well as from what I have looked at in other serialized forms, magazines, television, comics, etc., I think Dickens had both the whole and the part in mind to some degree and this degree seems much varied when comparing episodes. In fact comparing television and comic story serialization shows a lot of similarity where a series may have a rough undefined goal and develop over a series of episode runs, with occasional one offs that are self-contained thrown in the mix. But my overall point is that my picture is far from complete and in following the various threads that are making the composite idea I have of the author, I am constantly challenged by false leads, inaccurate conclusions, unfathomable evidence, and irrelevant rabbit holes that I am prone to follow for too long of a time. Thankfully, there are posts like those I mentioned above to help guide me, but I like to think there is much more to the Dickens picture than has already been established and hope we may make some contribution to that. And based on how my picture is defining since I have been a member of the group, that is the case.

message 59:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 01, 2024 10:15AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What interesting comments we have had between installments! Thanks all. They could run and run, but I’ll just confirm Jim’s thought on the development of writing style between this and Dombey and Son, that the difference was partly due to his planning.

We learned in our group read that Dombey and Son was the first novel where Charles Dickens wrote “mems”, and planned it as meticulously as he ever really did. It was his own “point of peripety” if you like, where he changed direction. Charles Dickens was still to write in installments actually, for every single novel, but having a solid plan made a great deal of difference.

In Nicholas Nickleby, Charles Dickens wanted to write something more ambitious than either The Pickwick Papers or Oliver Twist but even apart from his contract to write something similar to The Pickwick Papers, to keep his audience Charles Dickens had to stay recognisably the same author, with the same concerns and mode of expression.

Nevertheless he allowed himself the freedom in these earlier pieces to respond to all the current events in his life. We can tell from the lack of any theatrical people on the installment wrapper (cover) by Hablot Knight Browne (at the top of this thread), that if Charles Dickens had never gone to the theatre in Portsmouth on that fateful day in early September 1838, to see the Infant Phenomenon Jean Davenport, we would never have been able to read about Vincent Crummles and his delightful theatre troupe.

It’s quite a thought! And is just one of the benefits of these largely unplanned serials, to set against the contrived “transformation of Lord Frederick’s character [which] is .. a bit of a stretch”, as you rightly say, Jim.

We learned in our group read that Dombey and Son was the first novel where Charles Dickens wrote “mems”, and planned it as meticulously as he ever really did. It was his own “point of peripety” if you like, where he changed direction. Charles Dickens was still to write in installments actually, for every single novel, but having a solid plan made a great deal of difference.

In Nicholas Nickleby, Charles Dickens wanted to write something more ambitious than either The Pickwick Papers or Oliver Twist but even apart from his contract to write something similar to The Pickwick Papers, to keep his audience Charles Dickens had to stay recognisably the same author, with the same concerns and mode of expression.

Nevertheless he allowed himself the freedom in these earlier pieces to respond to all the current events in his life. We can tell from the lack of any theatrical people on the installment wrapper (cover) by Hablot Knight Browne (at the top of this thread), that if Charles Dickens had never gone to the theatre in Portsmouth on that fateful day in early September 1838, to see the Infant Phenomenon Jean Davenport, we would never have been able to read about Vincent Crummles and his delightful theatre troupe.

It’s quite a thought! And is just one of the benefits of these largely unplanned serials, to set against the contrived “transformation of Lord Frederick’s character [which] is .. a bit of a stretch”, as you rightly say, Jim.

message 60:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 05, 2024 06:35AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Installment 17:

Chapter 52: Nicholas despairs of rescuing Madeline Bray, but plucks up his Spirits again, and determines to attempt it. Domestic Intelligence of the Kenwigses and Lillyvicks

This chapter follows straight on from Nicholas’s story.

When Nicholas hears Newman Noggs shouting, “Stop, thief!” he stops immediately, fearing that bystanders may be violent when they lay hands on him. He waits for Noggs to breathlessly catch him up.

Nicholas says he is planning to go and see Bray, hoping to awaken any affection the man has for his daughter, to save her. Newman tells him he won’t let him, so Nicholas then decides to go to his uncle, saying that he will drag him out of bed if necessary, but Newman persuades him from doing that as well.

Nicholas is in despair, saying:

“‘There seems no ray of hope’…

‘The greater necessity for coolness, for reason, for consideration, for thought,’ said Newman“

He suggests talking to the Cheeryble brothers, but Nicholas tells him they are out of the country on business. Newman then suggests talking to their nephew or their old clerk but Nicholas dismisses this idea. They would not be able to do any more than he can, and it would mean him breaking the confidence that Charles Cheerybles had placed him in.

Is there no way, Newman asks? But Nicholas says, in utter dejection:

“Not one. The father urges, the daughter consents. These demons have her in their toils; legal right, might, power, money, and every influence are on their side. How can I hope to save her?”

Newman says that when all else fails, one should never give up hope. Do all you can, but never give up hope or is is useless to try anything. Nicholas badly needed this encouragement, and he decides he will visit Madeline herself the next day, to try to reason with her. Newman Noggs thinks this is a very good idea, and Nicholas dashes off, unable to keep still in his agitation.

“He’s a violent youth at times,’ said Newman, looking after him; ‘and yet I like him for it. There’s cause enough now.”

Meanwhile, Miss Morleena Kenwigs has been invited by a neighbour to a demonstration dance held by a dancing master aboard a steamer going from Westminster Bridge to the Eel-pie Island at Twickenham. There will be a band and a buffet, and the dancing master hopes to attract many new pupils.

“Mrs Kenwigs rightly deem[ed] that the honour of the family was involved in Miss Morleena’s making the most splendid appearance possible on so short a notice, and … that other people’s children could learn to be genteel besides theirs”

In her efforts “to sustain the family name or perish in the attempt” she had fainted twice with the effort of getting Morleena ready

but the her mother notices that her hair needs cutting too, and slaps Morleena for being ungrateful.

“‘I can’t help it, ma,’ replied Morleena, also in tears; ‘my hair will grow.’”

Mrs Kenwigs says she can’t even send her daughter to the hairdresser’s on her own, as she would be bound to reveal what she would be wearing, to Laura Chopkins “the daughter of the ambitious neighbour” who had invited her.

Hearing Noggs outside in the hall, Mrs. Kenwigs asks him to take Morleena to the hairdresser.

“It was not exactly a hairdresser’s; that is to say, people of a coarse and vulgar turn of mind might have called it a barber’s; for they not only cut and curled ladies elegantly, and children carefully, but shaved gentlemen easily. Still, it was a highly genteel establishment”

and is so genteel in fact that the hairdresser turns away a paying customer because he is a coal-heaver.

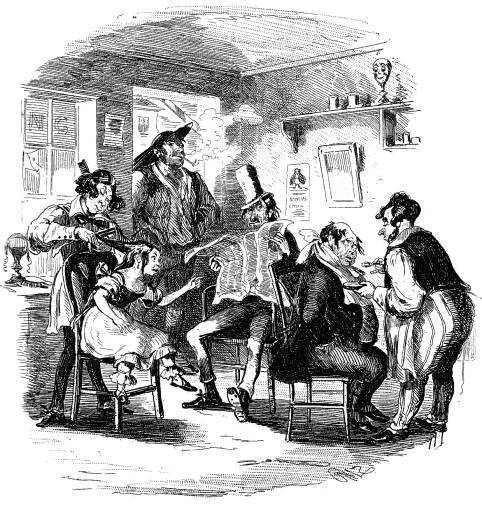

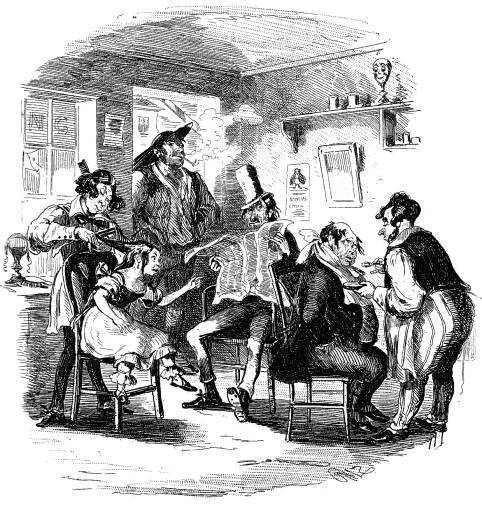

“Great Excitement of Miss Kenwigs at the Hairdresser’s Shop” - Hablot K. Browne (Phiz) - August 1839

Fortunately the coal-heaver is good-natured about it, grins at Newman Noggs, who appears highly entertained, and whistles on his way out of the shop.

“The proprietor, know[s] that Miss Kenwigs had three sisters, each with two flaxen tails, and all good for sixpence apiece, once a month at least”

and cannily leaves the melancholy old gentleman he has just lathered, to be shaved by his temporary staff. But Morleena gives a little scream, as she has recognised her great-uncle:

“The features of Mr. Lillyvick they were, but strangely altered. If ever an old gentleman had made a point of appearing in public, shaved close and clean, that old gentleman was Mr. Lillyvick. [He had] assumed, before all men, a solemn and portentous dignity … And now, there he sat, with the remains of a beard at least a week old encumbering his chin; a soiled and crumpled shirt-frill, … abashed and drooping, despondent, and expressive of such humiliation, grief, and shame.”

Newman Noggs recognises Mr. Lillyvick, and says his name. Mr. Lillyvick is depressed and morose, but asks whether Mrs. Kenwigs has had a son, and whether it is like him, as he would like there to be someone like him before he dies. Morleena has not been able to resist listening to this, even though she is in danger of having her ears snipped off rather than her hair, by turning around in her chair.

Noggs wonders what could have happened to make Mr Lillyvick so altered, but is of such a taciturn nature that he assumes he will find out eventually if he waits.

While they are walking back to the house, Mr Lillyvick asks if the Kenwigs had been upset by his marriage. Morleena says yes, it made her mother cry, and her father was very low for some time, but now they have recovered. My Lillyvick hesitates, and then asks if she would kiss him, if he asked her. Morleena says yes, but that she would never kiss her aunt Lillyvick. She says that she is is no aunt of hers. Mr Lillyvick picks her up and kisses her, walking straight up into the Kenwigs’s sitting-room and putting Morleena down in the middle:

“Mr. and Mrs. Kenwigs were at supper. At sight of their perjured relative, Mrs Kenwigs turned faint and pale, and Mr. Kenwigs rose majestically.”

They are not happy to see Mr Lillyvick, even though he has put out his hand to greet them. But as soon as Mr Lillyvick starts talking about the baby, saying how pleased he is that he is healthy, and wondering what name they will give the baby, and berating himself for turning his back on them, Mr and Mrs Kenwigs are mollified.

When Mrs Kenwigs is able to speak again, after all her tears, she says that she would never have believed he could have turned his back on them, after being so kind and affectionate. They never cared about the money or property; they scorned it. They could never quarrel with Mrs Kenwigs’s uncle, but will never receive his wife.

“And, here, the emotions of Mrs Kenwigs became so violent, that Mr. Kenwigs was fain to administer hartshorn internally, and vinegar externally, and to destroy a staylace, four petticoat strings, and several small buttons.”

“The Upside of a Marital Breakdown” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

“Mrs. Kenwigs threw herself upon the old gentleman’s neck.”

When she is a little more composed, Mr. Lillyvick reveals that his wife has eloped with a half-pay “bottle-nosed captain”.

“’It was in this room,’ said Mr. Lillyvick, looking sternly round, ‘that I first see Henrietta Petowker. It is in this room that I turn her off, for ever.’”

Mr and Mrs Kenwigs are then overcome with sympathy for Mr Kenwigs’s sufferings:

“Mrs. Kenwigs was horror-stricken to think that she should ever have nourished in her bosom such a snake, adder, viper, serpent, and base crocodile as Henrietta Petowker …

Mr. Kenwigs remembered that he had had his suspicions, but did not wonder why Mrs. Kenwigs had not had hers, as she was all chastity, purity, and truth, and Henrietta all baseness, falsehood, and deceit. “

Mr. Lillyvick then tells them he will once again leave the money he had intended to leave to their children, and that Noggs will witness his will the next morning. He says that he had humoured his wife in everything, but that this all took place 20 miles away. Mr Lillyvick tearfully reveals that his wife had also taken some valuable teaspoons and £24 in sovereigns when she ran away from him.

The Kenwigs family rally round in support, and make him stay for a good supper. Mr Lillyvick, now returned to his family:

“seemed, though still very humble, quite resigned to his fate, and rather relieved than otherwise by the flight of his wife.”

Chapter 52: Nicholas despairs of rescuing Madeline Bray, but plucks up his Spirits again, and determines to attempt it. Domestic Intelligence of the Kenwigses and Lillyvicks

This chapter follows straight on from Nicholas’s story.

When Nicholas hears Newman Noggs shouting, “Stop, thief!” he stops immediately, fearing that bystanders may be violent when they lay hands on him. He waits for Noggs to breathlessly catch him up.

Nicholas says he is planning to go and see Bray, hoping to awaken any affection the man has for his daughter, to save her. Newman tells him he won’t let him, so Nicholas then decides to go to his uncle, saying that he will drag him out of bed if necessary, but Newman persuades him from doing that as well.

Nicholas is in despair, saying:

“‘There seems no ray of hope’…

‘The greater necessity for coolness, for reason, for consideration, for thought,’ said Newman“

He suggests talking to the Cheeryble brothers, but Nicholas tells him they are out of the country on business. Newman then suggests talking to their nephew or their old clerk but Nicholas dismisses this idea. They would not be able to do any more than he can, and it would mean him breaking the confidence that Charles Cheerybles had placed him in.

Is there no way, Newman asks? But Nicholas says, in utter dejection:

“Not one. The father urges, the daughter consents. These demons have her in their toils; legal right, might, power, money, and every influence are on their side. How can I hope to save her?”

Newman says that when all else fails, one should never give up hope. Do all you can, but never give up hope or is is useless to try anything. Nicholas badly needed this encouragement, and he decides he will visit Madeline herself the next day, to try to reason with her. Newman Noggs thinks this is a very good idea, and Nicholas dashes off, unable to keep still in his agitation.

“He’s a violent youth at times,’ said Newman, looking after him; ‘and yet I like him for it. There’s cause enough now.”

Meanwhile, Miss Morleena Kenwigs has been invited by a neighbour to a demonstration dance held by a dancing master aboard a steamer going from Westminster Bridge to the Eel-pie Island at Twickenham. There will be a band and a buffet, and the dancing master hopes to attract many new pupils.

“Mrs Kenwigs rightly deem[ed] that the honour of the family was involved in Miss Morleena’s making the most splendid appearance possible on so short a notice, and … that other people’s children could learn to be genteel besides theirs”

In her efforts “to sustain the family name or perish in the attempt” she had fainted twice with the effort of getting Morleena ready

but the her mother notices that her hair needs cutting too, and slaps Morleena for being ungrateful.

“‘I can’t help it, ma,’ replied Morleena, also in tears; ‘my hair will grow.’”

Mrs Kenwigs says she can’t even send her daughter to the hairdresser’s on her own, as she would be bound to reveal what she would be wearing, to Laura Chopkins “the daughter of the ambitious neighbour” who had invited her.

Hearing Noggs outside in the hall, Mrs. Kenwigs asks him to take Morleena to the hairdresser.

“It was not exactly a hairdresser’s; that is to say, people of a coarse and vulgar turn of mind might have called it a barber’s; for they not only cut and curled ladies elegantly, and children carefully, but shaved gentlemen easily. Still, it was a highly genteel establishment”

and is so genteel in fact that the hairdresser turns away a paying customer because he is a coal-heaver.

“Great Excitement of Miss Kenwigs at the Hairdresser’s Shop” - Hablot K. Browne (Phiz) - August 1839

Fortunately the coal-heaver is good-natured about it, grins at Newman Noggs, who appears highly entertained, and whistles on his way out of the shop.

“The proprietor, know[s] that Miss Kenwigs had three sisters, each with two flaxen tails, and all good for sixpence apiece, once a month at least”

and cannily leaves the melancholy old gentleman he has just lathered, to be shaved by his temporary staff. But Morleena gives a little scream, as she has recognised her great-uncle:

“The features of Mr. Lillyvick they were, but strangely altered. If ever an old gentleman had made a point of appearing in public, shaved close and clean, that old gentleman was Mr. Lillyvick. [He had] assumed, before all men, a solemn and portentous dignity … And now, there he sat, with the remains of a beard at least a week old encumbering his chin; a soiled and crumpled shirt-frill, … abashed and drooping, despondent, and expressive of such humiliation, grief, and shame.”

Newman Noggs recognises Mr. Lillyvick, and says his name. Mr. Lillyvick is depressed and morose, but asks whether Mrs. Kenwigs has had a son, and whether it is like him, as he would like there to be someone like him before he dies. Morleena has not been able to resist listening to this, even though she is in danger of having her ears snipped off rather than her hair, by turning around in her chair.

Noggs wonders what could have happened to make Mr Lillyvick so altered, but is of such a taciturn nature that he assumes he will find out eventually if he waits.

While they are walking back to the house, Mr Lillyvick asks if the Kenwigs had been upset by his marriage. Morleena says yes, it made her mother cry, and her father was very low for some time, but now they have recovered. My Lillyvick hesitates, and then asks if she would kiss him, if he asked her. Morleena says yes, but that she would never kiss her aunt Lillyvick. She says that she is is no aunt of hers. Mr Lillyvick picks her up and kisses her, walking straight up into the Kenwigs’s sitting-room and putting Morleena down in the middle:

“Mr. and Mrs. Kenwigs were at supper. At sight of their perjured relative, Mrs Kenwigs turned faint and pale, and Mr. Kenwigs rose majestically.”

They are not happy to see Mr Lillyvick, even though he has put out his hand to greet them. But as soon as Mr Lillyvick starts talking about the baby, saying how pleased he is that he is healthy, and wondering what name they will give the baby, and berating himself for turning his back on them, Mr and Mrs Kenwigs are mollified.

When Mrs Kenwigs is able to speak again, after all her tears, she says that she would never have believed he could have turned his back on them, after being so kind and affectionate. They never cared about the money or property; they scorned it. They could never quarrel with Mrs Kenwigs’s uncle, but will never receive his wife.

“And, here, the emotions of Mrs Kenwigs became so violent, that Mr. Kenwigs was fain to administer hartshorn internally, and vinegar externally, and to destroy a staylace, four petticoat strings, and several small buttons.”

“The Upside of a Marital Breakdown” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

“Mrs. Kenwigs threw herself upon the old gentleman’s neck.”

When she is a little more composed, Mr. Lillyvick reveals that his wife has eloped with a half-pay “bottle-nosed captain”.

“’It was in this room,’ said Mr. Lillyvick, looking sternly round, ‘that I first see Henrietta Petowker. It is in this room that I turn her off, for ever.’”

Mr and Mrs Kenwigs are then overcome with sympathy for Mr Kenwigs’s sufferings:

“Mrs. Kenwigs was horror-stricken to think that she should ever have nourished in her bosom such a snake, adder, viper, serpent, and base crocodile as Henrietta Petowker …

Mr. Kenwigs remembered that he had had his suspicions, but did not wonder why Mrs. Kenwigs had not had hers, as she was all chastity, purity, and truth, and Henrietta all baseness, falsehood, and deceit. “

Mr. Lillyvick then tells them he will once again leave the money he had intended to leave to their children, and that Noggs will witness his will the next morning. He says that he had humoured his wife in everything, but that this all took place 20 miles away. Mr Lillyvick tearfully reveals that his wife had also taken some valuable teaspoons and £24 in sovereigns when she ran away from him.

The Kenwigs family rally round in support, and make him stay for a good supper. Mr Lillyvick, now returned to his family:

“seemed, though still very humble, quite resigned to his fate, and rather relieved than otherwise by the flight of his wife.”

message 61:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 02, 2024 05:00AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Class and Money

The Kenwigs family have been good fare for Charles Dickens’s class satire. Mrs Kenwigs married beneath her, and their aspirations to gentility all now hinge on her uncle Lillyick, the water rates collector. But they do not seem quite as obsessed with their social position as the Wititterlys, who were willing for Kate to undergo any indignities and ignore the vulgarism of Sir Mulberry Hawk, because he was an aristocrat. Both Mrs Wititterly and the pretentious Miss Knag used Kate as a foil for their own vanity.

Mrs Wititterly especially aimed at social pretensions which are also moral failings. Mrs Nickleby also did this initially, although the aspirations were partly for her children. The Kenwigs too are aspirational for their children, and although we might consider the example they set not a very good one (I am remembering Morleena “fainting” into a chair!) the children are well cared for and appear to be loved. How much of the welcome back to the bosom of the family for Mr Lillyick is sincere and how much motivated by avarice is debatable.

Mr Lillyvick himself as an example of lower gentility, has been portrayed up to now as self-important, selfish, pompous and grandiose. He has been much like Wackford Squeers (although without the cruelty), with his imperious manner and unconcern for others - although he might be slightly less ignorant. We see another side to him in this chapter though; a more chastened Mr Lillivick, who intends to do the best for his great-nieces, although it is interesting that he still sees this only in monetary terms.

Money and avarice is the downfall of many a Charles Dickens character. Ralph Nickleby was the son of a gentleman, but has sacrificed all family feeling to his obsession with business; a common theme in several later novels by Charles Dickens. We cannot know what Arthur Gride’s origins were, but since he was Ralph’s mentor and has always been a money-lender, we have to assume that his hideous appearance and demeanour, foul living conditions and manners are due to this obsession with money. How things will pan out for these two we do not yet know.

Sir Mulberry Hawk and Lord Frederick Verisopht both reveal what Charles Dickens thoughts of as the failings of the aristocracy: Hawk wholly cruel and corrupt, and Lord Frederick fatally thoughtless. Walter Bray is another example of a gentleman whose dissolute habits and moral failings have led to a miserable poverty-stricken life. He is both pitiable and ruthless, helpless but frighteningly possessive (of his daughter). We wonder what his inability to resist temptation can eventually lead to. Will he go through with sacrificing his daughter to gain a better life for himself? It’s a bit tortuous, all his self-doubt and self-persuasion, but it does anticipate other characters in later Charles Dickens novels who are willing to sacrifice family members for greed or status.

Newman Noggs also used to be a gentleman (Ralph told the hot muffin and crumpet baking “entrepreneur” very early on, that Noggs used to keep horses) but because of his drinking habit has now sunk so low that he lives in a mean garret in the house managed by the Kenwigs.

His moral code is one of the few good examples though, and he has been an unfailing good source of help to Nicholas; his only true friend apart from Smike, so we hope for a good end for Newman Noggs.

All these satirical portraits are examples both of Charles Dickens’s strong moral code, and his persuasive writing.

The Kenwigs family have been good fare for Charles Dickens’s class satire. Mrs Kenwigs married beneath her, and their aspirations to gentility all now hinge on her uncle Lillyick, the water rates collector. But they do not seem quite as obsessed with their social position as the Wititterlys, who were willing for Kate to undergo any indignities and ignore the vulgarism of Sir Mulberry Hawk, because he was an aristocrat. Both Mrs Wititterly and the pretentious Miss Knag used Kate as a foil for their own vanity.

Mrs Wititterly especially aimed at social pretensions which are also moral failings. Mrs Nickleby also did this initially, although the aspirations were partly for her children. The Kenwigs too are aspirational for their children, and although we might consider the example they set not a very good one (I am remembering Morleena “fainting” into a chair!) the children are well cared for and appear to be loved. How much of the welcome back to the bosom of the family for Mr Lillyick is sincere and how much motivated by avarice is debatable.

Mr Lillyvick himself as an example of lower gentility, has been portrayed up to now as self-important, selfish, pompous and grandiose. He has been much like Wackford Squeers (although without the cruelty), with his imperious manner and unconcern for others - although he might be slightly less ignorant. We see another side to him in this chapter though; a more chastened Mr Lillivick, who intends to do the best for his great-nieces, although it is interesting that he still sees this only in monetary terms.

Money and avarice is the downfall of many a Charles Dickens character. Ralph Nickleby was the son of a gentleman, but has sacrificed all family feeling to his obsession with business; a common theme in several later novels by Charles Dickens. We cannot know what Arthur Gride’s origins were, but since he was Ralph’s mentor and has always been a money-lender, we have to assume that his hideous appearance and demeanour, foul living conditions and manners are due to this obsession with money. How things will pan out for these two we do not yet know.

Sir Mulberry Hawk and Lord Frederick Verisopht both reveal what Charles Dickens thoughts of as the failings of the aristocracy: Hawk wholly cruel and corrupt, and Lord Frederick fatally thoughtless. Walter Bray is another example of a gentleman whose dissolute habits and moral failings have led to a miserable poverty-stricken life. He is both pitiable and ruthless, helpless but frighteningly possessive (of his daughter). We wonder what his inability to resist temptation can eventually lead to. Will he go through with sacrificing his daughter to gain a better life for himself? It’s a bit tortuous, all his self-doubt and self-persuasion, but it does anticipate other characters in later Charles Dickens novels who are willing to sacrifice family members for greed or status.

Newman Noggs also used to be a gentleman (Ralph told the hot muffin and crumpet baking “entrepreneur” very early on, that Noggs used to keep horses) but because of his drinking habit has now sunk so low that he lives in a mean garret in the house managed by the Kenwigs.

His moral code is one of the few good examples though, and he has been an unfailing good source of help to Nicholas; his only true friend apart from Smike, so we hope for a good end for Newman Noggs.

All these satirical portraits are examples both of Charles Dickens’s strong moral code, and his persuasive writing.

message 62:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 01, 2024 10:20AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I’ll choose a more serious one as my favourite quotation today, although I was tempted by Mrs Kenewig’s ridiculous affectations. They seem to be so much a part of her that perhaps she can no longer help them. But here is Noggs in contemplative mood:

“’He’s a violent youth at times,’ said Newman, looking after him; ‘and yet I like him for it. There’s cause enough now.’”

Noggs has such a good heart, chasing after Nicholas in case he does irreparable harm, with his passions so inflamed. But it’s slightly ironic since Noggs was the one who went chasing down the street crying “Stop thief!” to get attention.

“’He’s a violent youth at times,’ said Newman, looking after him; ‘and yet I like him for it. There’s cause enough now.’”

Noggs has such a good heart, chasing after Nicholas in case he does irreparable harm, with his passions so inflamed. But it’s slightly ironic since Noggs was the one who went chasing down the street crying “Stop thief!” to get attention.

message 63:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 01, 2024 10:21AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

So the Kenwigs and Mr Lillyvick are reunited. We had learned from Mr Crummles, just before he left for America that his new wife (Henrietta Petowker, as we knew her) was leading him a life of misery, so her eloping now probably is now the end of her story arc too. Four adults and six children all dealt with in one chapter; that must have pleased Charles Dickens!

Over to you 😊

Over to you 😊

Well leave it to Dickens to place an over the top satirical chapter after the gloomy creepiness of the previous chapter with Gride and the description of his house (which I thought was just another way for Dickens to describe Gride's personality.) The more Dickens features Noggs, the more there is to admire.

Well leave it to Dickens to place an over the top satirical chapter after the gloomy creepiness of the previous chapter with Gride and the description of his house (which I thought was just another way for Dickens to describe Gride's personality.) The more Dickens features Noggs, the more there is to admire.Thanks Jean for your discussion on class and money.

Another chapter to round up another family. Sorry that Henrietta turned out to be not a great choice for Mr. Lilyvick. Now he will be reunited with the Kenwigs who will get what they wanted! Is it a happy ending or not? And for whom? I’d say Mr. Lillyvick sadly went through some ups and downs with his errant marriage. But how could Henrietta just leave? She took his spoons and lots of money. Oh dear.

Another chapter to round up another family. Sorry that Henrietta turned out to be not a great choice for Mr. Lilyvick. Now he will be reunited with the Kenwigs who will get what they wanted! Is it a happy ending or not? And for whom? I’d say Mr. Lillyvick sadly went through some ups and downs with his errant marriage. But how could Henrietta just leave? She took his spoons and lots of money. Oh dear.Newman Noggs is right up there with Miss Betsey for me. What a guy despite his own fallibilities. I do love his message of HOPE which reminded me of Miss Betsey’s speech to young David Copperfield. I do hope for a good future for Noggs!

I thoroughly enjoyed the breakdown by character regarding money and class, Jean. Thank you so much for that.

I thoroughly enjoyed the breakdown by character regarding money and class, Jean. Thank you so much for that. Newman's statement about hope was definitely my favorite passage of the chapter. For those that may not celebrate Advent leading up to Christmas, the first week of Advent focuses on hope! What perfect timing. (The remaining three weeks' themes are peace, joy, and love. There are variations on this around the world, of course.)

I found myself feeling sympathetic to Mr Lillyvick in this chapter, but suspicious of the Kenwigs. You didn't care about the money? Interesting...

Kelly wrote: "I thoroughly enjoyed the breakdown by character regarding money and class, Jean. Thank you so much for that. "

Kelly wrote: "I thoroughly enjoyed the breakdown by character regarding money and class, Jean. Thank you so much for that. "Yes! Thank you, Jean. While I was reading your Class and Money post, I flashed back on watching Masterpiece Theatre when I was young, and at the end of the show, Alistair Cooke would come on and explain the history, dramatic elements, and/or character details, which left me feeling I understood it so much better. This seems the perfect time in this novel to provide these explanatory touches, and I appreciate it so much!

I’ve been traveling for the last two plus weeks and have not had internet access. I’ve kept up with the NN readings and discover that I’m somehow a few chapters ahead, as I’ve read 54. So, for the next few days I’ll be reading the 180 messages about NN that I’ve missed! I don’t want to miss a comment from anyone.

I’ve been traveling for the last two plus weeks and have not had internet access. I’ve kept up with the NN readings and discover that I’m somehow a few chapters ahead, as I’ve read 54. So, for the next few days I’ll be reading the 180 messages about NN that I’ve missed! I don’t want to miss a comment from anyone.My favorite chapters are those which move the plot forward, which I think of being the “serious” ones.

message 69:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 02, 2024 09:48AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Great to see you back Kathleen!

And don't worry, you won't have miscounted - we added a couple of extra free days. 🙄 So yes, please do read everyone's comments, and if anyone missed my long one on Charles Dickens's writing style LINK HERE - which was triggered by a comment of Werner's - you might find that interesting (as well as the follow-ups by Jim, Werner and Sam).

It's really more the sort of discussion we might have at the end. Thinking back over all the variety of works we have read by him, Charles Dickens is pretty near impossible to slot into any of the convenient literary genres, and whenever we try to, there he will be in our minds saying "Well what about my "x" (work)?"

It's interesting that you prefer the chapters "which move the plot forward" Kathleen, as the story element is still so important in modern fiction, isn't it? As we near the end, there are more chapters of this sort, but there will still be bizarre, grotesque, spiritual, out-of-body or mesmeric parts - and a bit of soliloquising too!

Thanks all, for your incisive thoughts, and lovely appreciation of my "extras" - and see what you think to today's eventful chapter 😊 (Kathleen, you must be happy at the titles of the 3 chapters in this installment😆)

And don't worry, you won't have miscounted - we added a couple of extra free days. 🙄 So yes, please do read everyone's comments, and if anyone missed my long one on Charles Dickens's writing style LINK HERE - which was triggered by a comment of Werner's - you might find that interesting (as well as the follow-ups by Jim, Werner and Sam).

It's really more the sort of discussion we might have at the end. Thinking back over all the variety of works we have read by him, Charles Dickens is pretty near impossible to slot into any of the convenient literary genres, and whenever we try to, there he will be in our minds saying "Well what about my "x" (work)?"

It's interesting that you prefer the chapters "which move the plot forward" Kathleen, as the story element is still so important in modern fiction, isn't it? As we near the end, there are more chapters of this sort, but there will still be bizarre, grotesque, spiritual, out-of-body or mesmeric parts - and a bit of soliloquising too!

Thanks all, for your incisive thoughts, and lovely appreciation of my "extras" - and see what you think to today's eventful chapter 😊 (Kathleen, you must be happy at the titles of the 3 chapters in this installment😆)

message 70:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 02, 2024 09:46AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 53: Containing the further Progress of the Plot contrived by Mr. Ralph Nickleby and Mr. Arthur Gride

Nicholas has not slept all night, and although he is impulsive and excitable by nature, he is resolved to make an appeal to Madeline, as his last hope to save her. Morning brings him fresh energy, but also fresh doubts and misgivings, as his hope wanes.

However he is impatient to lose no time, and so Nicholas leaves early in the morning, even though it will be several hours before he can call on Madeline. The night before, he had been more confident in being able to persuade her. In the morning light, he feels less certain as he reflects on how unfair the world is. In this world, the virtuous often suffer and die while the evil-minded prosper:

“how youth and beauty died, and ugly griping age lived tottering on; how crafty avarice grew rich, and manly honest hearts were poor and sad”

When he arrives where she lives, the front door has been left ajar, so he walks upstairs and knocks gently at the door of the room where he has been admitted before. Madeline and her father are sitting alone in the room. It is just less than 3 weeks since he has seen Madeline, but he notices a great change in her appearance. She is ghastly white, and her expression seems fixed, as if she is struggling to maintain a mask that hides her emotions. Mr Bray seems anxious. Although he makes an appearance of being happy, he cannot look directly at his daughter. Madeline has not filled the vases with flowers or removed the cover from the bird cage, as is her habit. Nor is she engaged in her usual occupations. All this Nicholas takes in at a glance.

Mr. Bray demands that Nicholas state his business and leave. Madeline moves forward towards him with her arm outstretched, as if expecting a letter or order. Nicholas explains that his employers are abroad, so he has no letter at the moment. Mr. Bray sneers at Nicholas, looking down on him as a mere agent, whereas he is a gentleman. He challenges him, saying he supposes that he believes that he and Madeline will starve without the commissions for her work. Nicholas replies that he has not thought about it.

Irritated, Mr Bray tells Nicholas that his daughter is no longer to complete any orders, putting an emphasis on the word as being most ungenteel.

“‘And this is the independence of a man who sells his daughter as he has sold that weeping girl!’ thought Nicholas.”

But aloud, Nicholas retorts that Mr. Bray is doing his daughter a worse disservice by forcing her into a marriage than forcing her to support him. Madeline interrupts, begging Nicholas to remember that her father is ill. Her father is furious, and has a paroxysm. Nicholas leaves the room, signalling to Madeline to meet him outside on the stairs. He can hear her father recovering, and having no memory of what has transpired.

Madeline asks Nicholas to come in a couple of days, but Nicholas says that will be too late. She will be gone by then, and must hear him out. Her maid, her eyes red with weeping shows them into a side room. There Nicholas tells Madeline that he knows - probably better than she does - what kind of man she is marrying:

“I know what web is wound about you. I know what men they are from whom these schemes have come. You are betrayed and sold for money; for gold, whose every coin is rusted with tears, if not red with the blood of ruined men, who have fallen desperately by their own mad hands.”

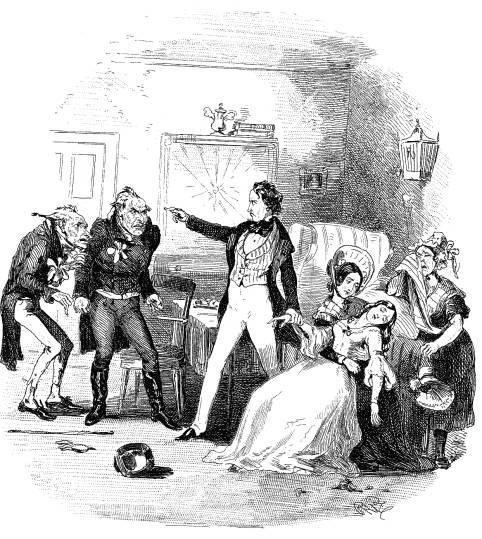

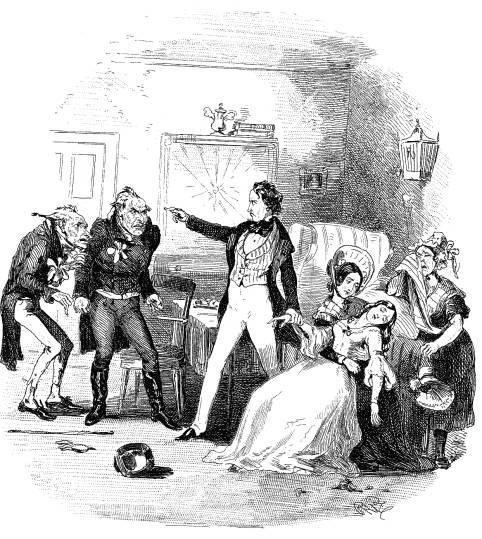

“I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful curse to which you have been impelled.” - Fred Barnard - 1875

But Madeline tells Nicholas that she has a duty to fulfil. She is not being forced but chooses to do it. Nicholas begs her to merely put the marriage off for one week. She is going to marry a villain, and even the worst poverty is better than that.

“Shrink from the loathsome companionship of this wretch as you would from corruption and disease. Suffer toil and labour if you will, but shun him, shun him, and be happy.”

Overcome with tears, Madeline admits that she does not love Arthur Gride, but believes that by marrying him she can restore her father to a comfortable life that might improve his health, and also:

“relieve a generous man [Charles Cheeryble] from the burden of assisting one, by whom, I grieve to say, his noble heart is little understood.”

Arthur Gride knows that she does not love him, and yet he still wants her to marry him. Madeline says that she can do her duty as a wife, and is grateful to Nicholas for trying to help her:

“But I do not repent, nor am I unhappy. I am happy in the prospect of all I can achieve so easily. I shall be more so when I look back upon it, and all is done, I know.”

Madeline says that her father looks happier than she has seen him in years, and she will not postpone the marriage. Nicholas tells her that her father’s behaviour is a trick to persuade her to go through with the marriage, and in an agony of supplication blocks her way when she tries to leave, imploring her to think again. He points out that she cannot withdraw from this commitment once she has taken her vows, and she will be forced into a bitter life of regret. But Madeline can hear her father calling and is resolved to go through with the marriage. Nicholas desperately tries one last thing:

“If this were a plot … not yet laid bare by me, but which, with time, I might unravel; if you were (not knowing it) entitled to fortune of your own, which, being recovered, would do all that this marriage can accomplish, would you not retract?”

but Madeline shrugs this off, thinking it is just a story. She urges Nicholas to tell the Cheeryble brothers that she is calm and happy, and to communicate her thanks and her blessings.

“She was gone. Nicholas, staggering from the house, thought of the hurried scene which had just closed upon him, as if it were the phantom of some wild, unquiet dream. The day wore on; at night, having been enabled in some measure to collect his thoughts, he issued forth again.”

That evening, Arthur Gride is in high spirits. His best bottle-green suit is ready, he has paid his housekeeper and thus everything is ready for the wedding. He is able to enjoy himself looking over his greasy and dirty old vellum-book with rusty clasps: his account book which he keeps at the bottom of a large chest, screwed to the floor. Gleefully he considers the record, which only he has ever seen, and which he knows to be true.

He begins to regret not having negotiated the marriage himself after seeing how much he must pay Ralph Nickleby. Altogether it will be £1,475 4s 3d by midday the next day. However, he realises that he would have had to pay Bray’s debt anyway, even if he hadn’t used Ralph, and begins to gloat again.

Peg Sliderskew interrupts him to show him the bird for the wedding breakfast, which the narrator comments is “a little, a very little one. Quite a phenomenon of a fowl. So very small and skinny.”

“The Wedding Feast” - Harry Furniss - 1910

“Arthur Gride chattered and mowed over his ledger until Peg Sliderskew interrupted him. ‘It’s the fowl’, said Peg, holding up a plate containing a phenomenally small and skinny one. ‘A beautiful bird!’ said Arthur.”

The price matches the size of the bird, but even so Peg warns him not to complain about the expense later, and Gride says they must live expensively for the first week and make up for the expense of it the following week. He jokes with Peg about how much she loves her old master, but she affects not to hear properly. He suspects her bad hearing to be selective, so that she doesn’t hear what she doesn’t want to hear. Nor does she seem to hear the doorbell, but he sends her off and resumes poring over his ledger with the lamp close to him.

“The room had no other light than that which it derived from a dim and dirt-clogged lamp, whose lazy wick, being still further obscured by a dark shade, cast its feeble rays over a very little space, and left all beyond in heavy shadow.”

Absorbed in his thoughts, Gride suddenly becomes aware of a stranger hovering over him.

“‘Thieves! thieves!’ shrieked the usurer, starting up and folding his book to his breast. ‘Robbers! Murder!’” - Fred Barnard - 1875

But the stranger tells him he is not there to attack him. There is no need for Gride to know his name, but he has been waiting to get his attention.

Arthur Gride perceives that the stranger is a young man, of good manner and bearing, and is reassured. The stranger tells Gride that the lady he wants to marry loathes him:

“Her blood runs cold at the mention of your name; the vulture and the lamb, the rat and the dove, could not be worse matched than you and she. You see I know her.”

He knows that Arthur Gride and Ralph Nickleby have hatched a plot, and that:

“You pay him for his share in bringing about this sale of Madeline Bray”

The stranger (whom the narrator now tells us is Nicholas) further knows that they are planning to defraud her. He tells Gride that people are on his trail:

“If the energy of man can compass the discovery of your fraud and treachery before your death; if wealth, revenge, and just hatred, can hunt and track you through your windings; you will yet be called to a dear account for this. We are on the scent already; judge you, who know what we do not, when we shall have you down!”

and they mean to have him convicted. Since he can’t appeal to Arthur Gride’s humanity, he asks how much money will it take to buy him off. Nicholas guesses that Arthur Gride is skeptical about being paid, but says that Madeline’s friends will pay—he must just postpone the marriage a few days.

At first, Arthur things that Ralph has betrayed him, and wonders about both Bray and Madeline. However, he begins to believe his visitor has made a lucky guess, but doesn’t really know enough about his schemes to be a threat. He does not believe this stranger’s promise of payment by friends, and thinks that it is merely a tactic to delay the nuptials. Arthur Gride:

“trembled with passion at his boldness and audacity, ‘I’d have that dainty chick for my wife, and cheat you of her, young smooth-face!’”

He has gained a knack of summing people up, after many years, and calculating the odds in his favour. Gride opens the windows wide and starts to shout that he is being robbed and murdered, grinning at Nicholas. Gride is jubilant when he realised that this stranger is in love with her. He taunts Nicholas that he has taken Madeline from him, even though he is old and ugly.

“But you shan’t have her, nor she you. She’s my wife, my doting little wife. Do you think she’ll miss you? Do you think she’ll weep? I shall like to see her weep, I shan’t mind it. She looks prettier in tears.”

Nicholas is enraged, but protests that he is not Madeline’s lover. She does not even know his name. Seeing Nicholas’ expression, which promises violence, he shouts out of the window again. Nicholas stalks out.

Arthur reflects how triumphant his wedding day will be tomorrow. He is glad he did not shout too loud, so that nobody came. Maybe this young man will commit suicide in despair. He locks all the doors and goes to bed, momentarily considering kissing Peg Sliderskew’s shrivelled lips first in his jubilation, but deciding against it.

Nicholas has not slept all night, and although he is impulsive and excitable by nature, he is resolved to make an appeal to Madeline, as his last hope to save her. Morning brings him fresh energy, but also fresh doubts and misgivings, as his hope wanes.

However he is impatient to lose no time, and so Nicholas leaves early in the morning, even though it will be several hours before he can call on Madeline. The night before, he had been more confident in being able to persuade her. In the morning light, he feels less certain as he reflects on how unfair the world is. In this world, the virtuous often suffer and die while the evil-minded prosper:

“how youth and beauty died, and ugly griping age lived tottering on; how crafty avarice grew rich, and manly honest hearts were poor and sad”

When he arrives where she lives, the front door has been left ajar, so he walks upstairs and knocks gently at the door of the room where he has been admitted before. Madeline and her father are sitting alone in the room. It is just less than 3 weeks since he has seen Madeline, but he notices a great change in her appearance. She is ghastly white, and her expression seems fixed, as if she is struggling to maintain a mask that hides her emotions. Mr Bray seems anxious. Although he makes an appearance of being happy, he cannot look directly at his daughter. Madeline has not filled the vases with flowers or removed the cover from the bird cage, as is her habit. Nor is she engaged in her usual occupations. All this Nicholas takes in at a glance.

Mr. Bray demands that Nicholas state his business and leave. Madeline moves forward towards him with her arm outstretched, as if expecting a letter or order. Nicholas explains that his employers are abroad, so he has no letter at the moment. Mr. Bray sneers at Nicholas, looking down on him as a mere agent, whereas he is a gentleman. He challenges him, saying he supposes that he believes that he and Madeline will starve without the commissions for her work. Nicholas replies that he has not thought about it.

Irritated, Mr Bray tells Nicholas that his daughter is no longer to complete any orders, putting an emphasis on the word as being most ungenteel.

“‘And this is the independence of a man who sells his daughter as he has sold that weeping girl!’ thought Nicholas.”