Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

This topic is about

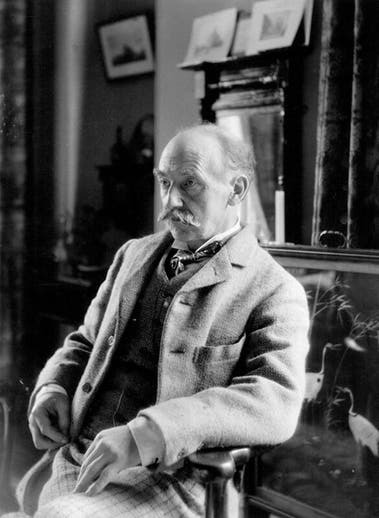

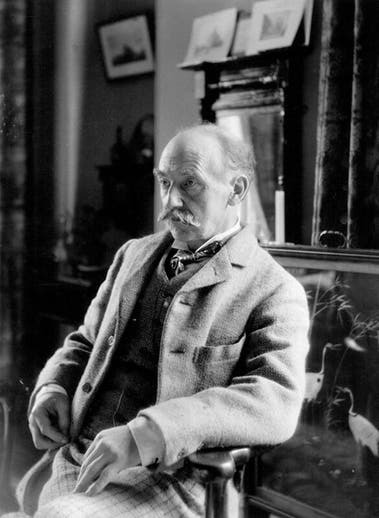

Thomas Hardy

General Interest

>

Thomas Hardy: The Time-Torn Man, by Claire Tomalin

Brian E wrote: "Bridget, but I had been waiting for notification that you had posted something here and I was never notified. The last notification I had was for the post on December 13th. I finally checked just n..."

Hi Brian! Thanks for checking in. I have the same struggles with Goodreads. Either I miss notifications, or I get waaaaay too many. I have also been distracted from reading this biography by my "real life" so you are not alone in that. I'm just starting to read Chapter 12 today. Will post something either later tonight or tomorrow. Please respond whenever you can, and please please do enjoy your family to the fullest! Happy Holidays!!

Hi Brian! Thanks for checking in. I have the same struggles with Goodreads. Either I miss notifications, or I get waaaaay too many. I have also been distracted from reading this biography by my "real life" so you are not alone in that. I'm just starting to read Chapter 12 today. Will post something either later tonight or tomorrow. Please respond whenever you can, and please please do enjoy your family to the fullest! Happy Holidays!!

Chapter 12: Hardy Joins a Club

This chapter spans the years 1877-1881. During this time, Emma and Tom move back to London so he can be closer to publishers and other writers. It makes perfect sense that Tom would need to be closer to London. So, they rent a house in Tooting. The house still stands at 172 Trinity Road. It’s even got a blue plaque commemorating Hardy’s stay there.

Hardy wrote two novels here: The Trumpet-Major and A Laodicean: A Story of Today. I did not encounter any spoilers as Tomalin described these stories.

The “club” in the title of this chapter refers to “social clubs”, or a gentleman’s club, like one sees on period dramas. Essentially, it’s a place where men could go to get away from the women in their lives. They can even stay overnight in the rooms available for members. Tom uses the Savile Club as his address many times. It is a luxury available only to the wealthy. It is the success of Far From the Madding Crowd that give Hardy financial access to these places. Knowing a little of how insecure Hardy was with class differences, and his lack of education, I can imagine he must have been thrilled to belong to these clubs. It probably made him feel – to some extent – like he had been accepted into the society he wanted.

His friendship with Mrs. Anne Procter (who he met through Leslie Stephens) also helped welcome Hardy into the literati circles of London in the 1880s. I liked learning about her and her circle. She strikes me as a the “Gertrude Stein” or 1880. How exciting it must have been for Tom to meet Tennyson in person! It was interesting how Tomalin weaved in speculation of how Emma reacted to Tom’s new fame and connections. Some people – like the Macmillians who were also outsiders being from Scotland – took to Emma right away, others did not.

The notes from, Richard Bowker (American representative of Harpers) were especially illuminating., They say positive things about Emma, but if you read between the lines, you can see she is overly concerned with Tom’s career. More than ever this chapter left me with the thought that if Tom and Emma had only had children, they might have had a happier marriage. First, there is the grief of being unable to conceive; but there is also the hole that was left in Emma’s life. She lacked purpose, and the easiest thing to give her life meaning was Tom’s writing. She thrives when Tom gets sick, and she becomes his secretary/manager and helps bring A Laodicean: A Story of Today to the publishers.

Financially though, things are going well for the Hardy’s now. The seed is planted in this chapter for the home they will eventually build in Dorchester.

This chapter spans the years 1877-1881. During this time, Emma and Tom move back to London so he can be closer to publishers and other writers. It makes perfect sense that Tom would need to be closer to London. So, they rent a house in Tooting. The house still stands at 172 Trinity Road. It’s even got a blue plaque commemorating Hardy’s stay there.

Hardy wrote two novels here: The Trumpet-Major and A Laodicean: A Story of Today. I did not encounter any spoilers as Tomalin described these stories.

The “club” in the title of this chapter refers to “social clubs”, or a gentleman’s club, like one sees on period dramas. Essentially, it’s a place where men could go to get away from the women in their lives. They can even stay overnight in the rooms available for members. Tom uses the Savile Club as his address many times. It is a luxury available only to the wealthy. It is the success of Far From the Madding Crowd that give Hardy financial access to these places. Knowing a little of how insecure Hardy was with class differences, and his lack of education, I can imagine he must have been thrilled to belong to these clubs. It probably made him feel – to some extent – like he had been accepted into the society he wanted.

His friendship with Mrs. Anne Procter (who he met through Leslie Stephens) also helped welcome Hardy into the literati circles of London in the 1880s. I liked learning about her and her circle. She strikes me as a the “Gertrude Stein” or 1880. How exciting it must have been for Tom to meet Tennyson in person! It was interesting how Tomalin weaved in speculation of how Emma reacted to Tom’s new fame and connections. Some people – like the Macmillians who were also outsiders being from Scotland – took to Emma right away, others did not.

The notes from, Richard Bowker (American representative of Harpers) were especially illuminating., They say positive things about Emma, but if you read between the lines, you can see she is overly concerned with Tom’s career. More than ever this chapter left me with the thought that if Tom and Emma had only had children, they might have had a happier marriage. First, there is the grief of being unable to conceive; but there is also the hole that was left in Emma’s life. She lacked purpose, and the easiest thing to give her life meaning was Tom’s writing. She thrives when Tom gets sick, and she becomes his secretary/manager and helps bring A Laodicean: A Story of Today to the publishers.

Financially though, things are going well for the Hardy’s now. The seed is planted in this chapter for the home they will eventually build in Dorchester.

The Hardy's Home in Tooting

If you are interested in more details about the Hardy Tooting home, here is a link to an article published in 2022 when the home went up for sale. In the article in mentions Hardy studying at King's College in 1860s. Technically this is true, but he only took night classes there. He was studying French. He was not matriculated as a proper student, as we know because he had a great deal of insecurity about not being as educated as his peers, like Horace Moule or Leslie Stephens.

https://www.countrylife.co.uk/propert...

If you are interested in more details about the Hardy Tooting home, here is a link to an article published in 2022 when the home went up for sale. In the article in mentions Hardy studying at King's College in 1860s. Technically this is true, but he only took night classes there. He was studying French. He was not matriculated as a proper student, as we know because he had a great deal of insecurity about not being as educated as his peers, like Horace Moule or Leslie Stephens.

https://www.countrylife.co.uk/propert...

Chapter 11: Dreaming the Heath - Comments

Chapter 11: Dreaming the Heath - Comments1. BRIDGET’S COMMENT

The first things that struck me for comment about the Hardy’s first home in Sturminster are things that struck Bridget too. I’ll add my 2 cents in, though:

a. Nature - As Bridget noted, Tomalin wrote descriptively about Sturminster and the surrounding area. If you add in the chapter title reference to the Heath at the center and it seems clear that Tomalin was purposely descriptive to mirror Hardy’s noted natural descriptiveness and character-like setting of Egdon Heath in the book he was writing at this time The Return of the Native

b. Childlessness - I knew Hardy did not have any children but was not aware of his or Emma’s desire to have them. Tomalin portrays their failure fairly poignantly, calling it “the saddest thing about their life together,” and had me feeling bad for them and for the marital troubles to come. I’m pretty sure that our having to be united when parenting together kept my wife and I distracted from giving weight to any petty differences we may have had during that time period.

c. Marriage - the depiction of Tom and Emma walking together did have me thinking that the marriage was in a relatively (for their marriage) good place during this two year period in Sturminster, likely helped by the closeness necessary when trying to have children. It is still too early for the inevitable frustration to become a detriment to the relationship.

2. THE RETURN OF THE NATIVE (TROTN)

a. Chapter Depiction - I anticipate that much of the chapter would be on the publishing history, writing process and other historical and biographical details surrounding TROTN, but I was a little surprised that so much of this chapter was about the plot and stylistic details of the novel. From how Tomalin describes the novel, it appears that she, like Tom, seems to regard it highly. Not that I disagree. Not in the least.

b. My POV on TROTN

- I first read TROTN back in 1979 to 1980 when I read all of Hardy’s Big 5, Tess, Jude, Mayor, Return & Madding. When I read it back then as a 26 to 27 year old, I wasn’t that impressed by it and preferred Tess, Mayor and especially Jude. When I re-read the Big 5 during the 2010s, I not only had aged 30-40 years but I had read all his other novels and had a better feel for the Hardy style and themes. This time around, TROTN impressed me more than any of the others. I still love Jude, but it does lose a bit on a re-read. I still rate Jude as my favorite Hardy because of how impactful of an experience my first read of it was.

- I appreciated the poetic descriptiveness of TROTN much more as a 60+ year old than as a young man. I especially appreciated his use of Egdon Heath as a character, portraying it similarly to how a castle is used in gothic novels. I think TROTN does have a certain gothic feel to it.

- A great novel, maybe the most representative of Hardy, but probably not the best to assign to high school kids. It was the one often assigned in my 1960s- early 70s high school days and, while I escaped its assignment, I know my older brother and sister who were assigned it were definite backers of its reputation as one of the most boring of the assigned classic books.

Brian E wrote: "I knew Hardy did not have any children but was not aware of his or Emma’s desire to have them. Tomalin portrays their failure fairly poignantly, calling it “the saddest thing about their life together,” and had me feeling bad for them and for the marital troubles to come.."

I'm glad you felt for the Hardys in the same way I did, Brian. I've known many couples who have had infertility issues, and its really a grief they have to process. It's so hard. I've known couples who did not survive the ordeal. It really does explain a lot of the struggles Tom and Emma had.

" I especially appreciated his use of Egdon Heath as a character"

I very much agree with you here. This is the start of Hardy's "Wessex" becoming a place that some people - even to this day - think is real. Hardy is so descriptive, the place becomes a character - as you said.

I'm so glad you got to re-read TROTN later in life. I've done that recently with "A Tale of Two Cities". I was assigned it in high school. But I didn't know enough about the history of the French revolution at the time, and the plight of the peasants in France to really appreciate what Dickens was writing. I read it last year with my son (who also had it assigned) and really loved it. I tried to explain some of the history to him, but I'm not sure what I said sank in. He may have to re-read it forty years later as well.

But right now I'm looking forward to my first read of TROTN. This biography is making me want to read so much more of Hardy.

Thanks for reading the biography along with me Brian!

I'm glad you felt for the Hardys in the same way I did, Brian. I've known many couples who have had infertility issues, and its really a grief they have to process. It's so hard. I've known couples who did not survive the ordeal. It really does explain a lot of the struggles Tom and Emma had.

" I especially appreciated his use of Egdon Heath as a character"

I very much agree with you here. This is the start of Hardy's "Wessex" becoming a place that some people - even to this day - think is real. Hardy is so descriptive, the place becomes a character - as you said.

I'm so glad you got to re-read TROTN later in life. I've done that recently with "A Tale of Two Cities". I was assigned it in high school. But I didn't know enough about the history of the French revolution at the time, and the plight of the peasants in France to really appreciate what Dickens was writing. I read it last year with my son (who also had it assigned) and really loved it. I tried to explain some of the history to him, but I'm not sure what I said sank in. He may have to re-read it forty years later as well.

But right now I'm looking forward to my first read of TROTN. This biography is making me want to read so much more of Hardy.

Thanks for reading the biography along with me Brian!

Bridget wrote: "Thanks for reading the biography along with me Brian!.."

Bridget wrote: "Thanks for reading the biography along with me Brian!.."Back at ya Bridget. This book does make for a good Buddy Read. And the slow pace works with this book because, even if it's a week between chapter readings, there is no loss of any plot thread details as would happen with fiction books or non-fiction works on subjects I'm unacquainted with. It's easy to get back to where you were.

Chapter 12: Hardy Joins a Club Comments

Chapter 12: Hardy Joins a Club Comments1. TOOTING

My flawed knowledge of Hardy’s life continues to bring me surprises. I was unaware that Tom and Emma would spend three years of their late 30s/early 40s life in London. They will stay there through the end of TROTN and 2 more novels before heading to Dorset. So Hardy will have issued 8 of his 14 novels before ending up in Dorset.

2. BRIDGET’S COMMENT

a. Savile Club - As Bridget noted, Hardy’s sensitivity to class must have made him proud to be a Savile Club member. I agree, but the Hardy insecurity still dominates and probably prevents him, as Tomalin notes, ever becoming a “clubbable man.” That’s just as well. It’s more fun getting my insight into that world from another favorite author, P.G. Wodehouse.

b. Anne Procter - It was great to read about Tom’s contact with other writers that his acquaintance with Ms. Proctor provided him. As Bridget noted, she seems like a Gertrude Stein for that time and place. I especially enjoyed that Tom met

- Henry James - a critic of his, and author that, according to Tom’s accurate analysis, was “without poetry, humor or spontaneity.” Yet Tom and Emma still liked to read James’ novels. I too feel that way about James yet still like to read his novels.

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson – reading books such as this and novels of the time remind me of just how popular Tennyson was at the time – he was a rock star/movie star of the time. I have to be reminded as he is not so widely read these days. But then poetry and poets were still preeminent back then with novels gradually obtaining their prominence over poetry in the early 20th Century. It’s too bad that Tom didn’t take Lord T up on his social invitations because, as Tomalin speculates, he was embarrassed by what she might say. Tom’s natural insecurities prevent his socializing with Lord T and being a more active clubbable man.

c. Marriage - the depiction of Tom being embarrassed by Emma saddened me. Tom himself notes that it was in Tooting House that their troubles began. As Emma entered her 40s, it would have been at this time that the permanent nature of the infertility problems would have hit home.

3. TWO MINOR NOVELS

I thought it interesting that after publishing one of his top class serious literary works, TROTN, Hardy went ahead and wrote two novels that Hardy himself characterizes as lesser novels. I found it a bit head scratching at first that Hardy spent his years in the literary center of Britain writing what he himself deems works of lesser literary value, ones that rank on Goodreads as having the 12th and 14th number of ratings out of is 14 novels.

a. The Trumpet Major - Hardy put this novel into the category of “Romances and Fantasies“ novels he considered of less literary caliber than his major literary works. Tomalin notes that he appeared to do so in order to write a book that would be more easily publishable and more befitting the public’s taste. I enjoyed it and only note that it is another Hardy, like UTGT and FFTMC with a heroine with 3 suitors

b. The Laodicean Not much is said about this novel, which is appropriate as it ranks as the Hardy with the least amount of GR ratings. While I enjoyed it, it is one of Hardy’s 3 Novels of Ingenuity, which Hardy himself considers of less literary value and , as they rank 11th 13th and 14th out of 14 in number of GR ratings for Hardy novels, is a sentiment the current reading public shares.

Since I bring it up in the previous post, I thought it best to post this list in case Bridget or anyone else hadn’t seen it before. It is from Wikipedia:

Since I bring it up in the previous post, I thought it best to post this list in case Bridget or anyone else hadn’t seen it before. It is from Wikipedia:In 1912, Hardy divided his novels and collected short stories into three classes:

Novels of Character and Environment

• The Poor Man and the Lady (1867, unpublished and lost)

• Under the Greenwood Tree: A Rural Painting of the Dutch School (1872)

• Far from the Madding Crowd (1874)

• The Return of the Native (1878)

• The Mayor of Casterbridge: The Life and Death of a Man of Character (1886)

• The Woodlanders (1887)

• Wessex Tales (1888, a collection of short stories)

• Tess of the d'Urbervilles: A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented (1891)

• Life's Little Ironies (1894, a collection of short stories)

• Jude the Obscure (1895)

Romances and Fantasies

• A Pair of Blue Eyes: A Novel (1873)

• The Trumpet-Major (1880)

• Two on a Tower: A Romance (1882)

• A Group of Noble Dames (1891, a collection of short stories)

• The Well-Beloved: A Sketch of a Temperament (1897) (first published as a serial in 1892)

Novels of Ingenuity

• Desperate Remedies: A Novel (1871)

• The Hand of Ethelberta: A Comedy in Chapters (1876)

• A Laodicean: A Story of To-day (1881)

Brian E wrote: "Since I bring it up in the previous post, I thought it best to post this list in case Bridget or anyone else hadn’t seen it before. It is from Wikipedia:

In 1912, Hardy divided his novels and collected short stories into three classes:.."

Brian, I read through your post about Chapter 12 and this list a couple days ago, and I meant to reply right away, but then I got distracted by my family :-). So, sorry this is late.

I love this list you posted! I didn't know Hardy made such a classification - what a wonderful tool Wikipedia can be. Placing this list at our finger tips! I'm so glad you copied it out in full instead of providing a link. It will be nice to refer back to as time goes on. Plus I love that it has all the publishing dates. I have a hard time remembering when each book was written.

Thank you!!

I have not read the "Novels of Ingenuity". What do you think he means with that word? Perhaps they were just hard to categorize any other way. Have you read any of them?

In 1912, Hardy divided his novels and collected short stories into three classes:.."

Brian, I read through your post about Chapter 12 and this list a couple days ago, and I meant to reply right away, but then I got distracted by my family :-). So, sorry this is late.

I love this list you posted! I didn't know Hardy made such a classification - what a wonderful tool Wikipedia can be. Placing this list at our finger tips! I'm so glad you copied it out in full instead of providing a link. It will be nice to refer back to as time goes on. Plus I love that it has all the publishing dates. I have a hard time remembering when each book was written.

Thank you!!

I have not read the "Novels of Ingenuity". What do you think he means with that word? Perhaps they were just hard to categorize any other way. Have you read any of them?

Brian E wrote: " So Hardy will have issued 8 of his 14 novels before ending up in Dorset.

..."

I had not done the math for this, but you are right! That's more than half the novels he will ever create. And as you point out, he's writing "unserious" novels while in the middle of literary London. Of course he was doing that to make money. Ironic that the lesser novels make more money for Hardy than the ones we think of as his master works.

"That’s just as well. It’s more fun getting my insight into that world from another favorite author, P.G. Wodehouse"

This is a great comment! I agree, there is no one as good as Wodehouse for giving us a glimpse of the club life!

"the depiction of Tom being embarrassed by Emma saddened me."

Yes, I agree! The Hardy marriage so often makes me sad. I know that it is going to lead to some amazing poetry, but it's still sad.

..."

I had not done the math for this, but you are right! That's more than half the novels he will ever create. And as you point out, he's writing "unserious" novels while in the middle of literary London. Of course he was doing that to make money. Ironic that the lesser novels make more money for Hardy than the ones we think of as his master works.

"That’s just as well. It’s more fun getting my insight into that world from another favorite author, P.G. Wodehouse"

This is a great comment! I agree, there is no one as good as Wodehouse for giving us a glimpse of the club life!

"the depiction of Tom being embarrassed by Emma saddened me."

Yes, I agree! The Hardy marriage so often makes me sad. I know that it is going to lead to some amazing poetry, but it's still sad.

Bridget wrote: " I read through your post about Chapter 12 and this list a couple days ago, and I meant to reply right away, but then I got distracted by my family :-). So, sorry this is late.

Bridget wrote: " I read through your post about Chapter 12 and this list a couple days ago, and I meant to reply right away, but then I got distracted by my family :-). So, sorry this is late. We've established that we are doing a leisurely Buddy Read which means never having to say you're sorry about being leisurely.

Bridget wrote: "I have not read the "Novels of Ingenuity". What do you think he means with that word? Perhaps they were just hard to categorize any other way. Have you read any of them?.."

I have read all Hardy's novels so I have read his 3 Novels of Ingenuity. While I hadn't thought too much about what he meant by that word, your question spurred me to think about it. Here's my thoughts:

1) Hardy wrote: Desperate Remedies to bein the style of the sensation novels so popular in mid-19th century Britain. In fact it's #13 on the Goodreads list of Sensation Novels: https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/1....

2) With The Hand of Ethelberta Hardy was trying to write a novel that was a romantic comedy, presumably using the term comedy in a broader sense.

3) I consider A Laodicean to also be like a sensation novel. It involves a woman inheriting a medieval castle and uses plot devices such as falsified telegrams and faked photographs that are atypical for Hardy but typical for sensation fiction

CONCLUSION: I think using the term "Ingenuity" is Hardy using a term that puts a positive spin on these works. I think a similar but more accurate term would be to call them Novels of Contrivances as contrivances abound in the Sensation novels and romantic comedies of the time period.

Chapter 13: The Tower

This chapter picks up where the last left off, with Tom and Emma still in Tooting but now Tom is healthy once again. Its April 1881 – and as a refresher (because I’m beginning to forget the timeline a bit), Tom and Emma have know each other for eleven years as they met in March 1870. They’ve been married for 7 years and lived in 7 different places. They blame Tom’s bad health on the London air and decide to leave the city once again for Dorset, this time in Wimborne, near the Hampshire border.

In June of 1881, a large comet is visible in England, and this seems to spur Hardy’s imagination towards astronomy. It fuels his next novel, Two on a Tower. As Tomalin writes about Hardy’s intrigue with the science of astronomy, I couldn’t help thinking about how often science finds its way into Hardy’s writing. I know we rightly associate Hardy with the natural world, with country fairs, and farm laborers; but there is also an undercurrent of burgeoning science and industrialization in his writing, so it was interesting to read about his astronomy curiosity. Actually, I think that interest predates Two on a Tower because he writes beautifully about the constellations in FFMC.

Tomalin describes much of the plot of Two on a Tower, and all should know it contains spoilers. But again, for me personally, the spoilers don’t seem to stick in my head. What I do remember is Two on a Tower contains another strong female lead character – a pattern that repeats and repeats in Hardy’s work. So many heroines. And once again Hardy is examining class with a rich Lady and a poor boy romance. I find it interesting that Tomalin says the “tower” itself is a center piece of the book

”a solid structure, a poetic dream place where things are possible that are not allowed in the real world”.

This strikes me as similar to what Brian describes in TROTN, where Egdon Heath itself is almost a character in the story. This is a hallmark of Hardy’s work, I think. The ability to make places come alive. Some people even today think Wessex is a real place, and not Hardy's fictional version of Dorchester. That's how powerful the sense of place is in his works.

The Hardy marriage seems content/stable in these years. Emma’s relationship with her sister seems strained by jealousy on Helen’s part. Too bad because Helen and her husband, Rev Holder, were part of Emma and Tom meeting at St. Juliot rectory. The Holders were always supportive of their relationship, but that connection seems to be gone in 1882 with the death of Rev Holder. And there isn’t any other family support for the couple now.

Most interesting was the chapter ending with Hardy publishing an essay about rural laborers. How their lives and education have improved, but how the fabric of the community is eroding. These are burgeoning thoughts Hardy will explore masterfully in the novels to come.

This chapter picks up where the last left off, with Tom and Emma still in Tooting but now Tom is healthy once again. Its April 1881 – and as a refresher (because I’m beginning to forget the timeline a bit), Tom and Emma have know each other for eleven years as they met in March 1870. They’ve been married for 7 years and lived in 7 different places. They blame Tom’s bad health on the London air and decide to leave the city once again for Dorset, this time in Wimborne, near the Hampshire border.

In June of 1881, a large comet is visible in England, and this seems to spur Hardy’s imagination towards astronomy. It fuels his next novel, Two on a Tower. As Tomalin writes about Hardy’s intrigue with the science of astronomy, I couldn’t help thinking about how often science finds its way into Hardy’s writing. I know we rightly associate Hardy with the natural world, with country fairs, and farm laborers; but there is also an undercurrent of burgeoning science and industrialization in his writing, so it was interesting to read about his astronomy curiosity. Actually, I think that interest predates Two on a Tower because he writes beautifully about the constellations in FFMC.

Tomalin describes much of the plot of Two on a Tower, and all should know it contains spoilers. But again, for me personally, the spoilers don’t seem to stick in my head. What I do remember is Two on a Tower contains another strong female lead character – a pattern that repeats and repeats in Hardy’s work. So many heroines. And once again Hardy is examining class with a rich Lady and a poor boy romance. I find it interesting that Tomalin says the “tower” itself is a center piece of the book

”a solid structure, a poetic dream place where things are possible that are not allowed in the real world”.

This strikes me as similar to what Brian describes in TROTN, where Egdon Heath itself is almost a character in the story. This is a hallmark of Hardy’s work, I think. The ability to make places come alive. Some people even today think Wessex is a real place, and not Hardy's fictional version of Dorchester. That's how powerful the sense of place is in his works.

The Hardy marriage seems content/stable in these years. Emma’s relationship with her sister seems strained by jealousy on Helen’s part. Too bad because Helen and her husband, Rev Holder, were part of Emma and Tom meeting at St. Juliot rectory. The Holders were always supportive of their relationship, but that connection seems to be gone in 1882 with the death of Rev Holder. And there isn’t any other family support for the couple now.

Most interesting was the chapter ending with Hardy publishing an essay about rural laborers. How their lives and education have improved, but how the fabric of the community is eroding. These are burgeoning thoughts Hardy will explore masterfully in the novels to come.

Chapter 13: The Tower - Comments

Chapter 13: The Tower - Comments1. TOM & EMMA MARRIAGE

As I don’t expect much marital bliss from Tom and Emma the fact that they seem to have no difficulties, strife or avoidance issues during this period is a positive. My conjecture is that the stress of returning to southwest England where their less-than-supportive families reside influenced them to give each other a break. An example is Emma’s difficulties with her sister that Bridget mentions.

I was very pleased that the couple returned to the locale of their honeymoon, Paris, and seemed to rekindle things a bit. Tomalin describes a fairly engaging month of leisurely pleasure for the couple, noting that for Emma ”it was the sort of jaunt she loved.” As to Tom, Tomalin does mention that “he was happy with Emma in Paris.”

The dedicated Tom chose to go on the Paris trip instead of making revisions to his novel Two on a Tower. It appears Tom thought the two of them needed some fun together time so I bet Tom entered the trip with an attitude to make it a success.

2. THE LAODICEAN

The chapter discusses two Hardy novels. Before he was writing Two on a Tower he was finishing The Laodicean. This is not a novel that Hardy seemed to enjoy writing or respect. Tomalin notes that for the ending installments, Tom was sick and just wanted to get it done. So, of course, the “result was poor and scrambled together.” For good reason, this novel ranks last of Hardy’s 14 novels in GR ratings.

3. TWO ON A TOWER

In contrast, Tom seemed to enjoy the process of both developing and writing his next novel, Two in a Tower. That made me feel a bit startled that Tom didn’t choose to do some final editing on this book. I think this was more because he was just satisfied with his effort on the book and not because he didn’t care about the novel. Perhaps Tom’s intent to write a more popular than literary work may have influenced his less perfectionist attitude toward the book.

Unlike with the Laodicean where Tom was dissatisfied and wanted to get the writing over with, Tom seemed to feel energized by writing this book. It was sparked by his own interest in astronomy and the upcoming real life Transit of Venus in the sky. Tom even sought out a real life tower he could use to visualize the tower observatory at the center of this novel. As Tomalin notes, Tom had “no trouble meeting deadlines” for the Atlantic Monthly serialization which indicates Tom’s ease with this writing effort.

When I read it, this novel felt a bit different from other Hardy novels to me and I enjoyed it more than I had anticipated. I often wondered why he didn’t categorize it with his Novels of Ingenuity because, as Tomalin notes, it has “the heavy paraphernalia of the Victorian thriller” where “coincidences pile up one after another.” Sounds just like the elements Hardy utilized in his other three Novels of Ingenuity. My conclusion is that Hardy categorized it with his “Romances and Fantasies” instead because, to Hardy, the book’s sensation elements were secondary in importance to the age and class differential romance he placed at the story’s center.

Chapter 14: The Conformers

2003 Film with Ciaran Hinds as Henchard

The year is 1883. Tom and Emma are renting a house in Dorchester. The land (an acre and a half) for Max Gate has been purchased. House plans are being drawn up, and the Hardy family will build it. Tom and Emma become fixtures in their little corner of Dorchester. Tom is a Justice of the Peace, and a sought after celebrity. Emma’s life is more solitary, I would even say uninteresting. She goes to church, she corresponds with friends, but there is no nest of family to which she belongs. She has no work to do. They aren’t travelling anymore. Therein come the “conformers” of the title. I think of it more like complacency. It reminds me of our feeling today that the suburbs are boring, that nothing happens there.

I thought this chapter would mostly be about the building of Max Gate, really this chapter is about the writing of The Mayor of Casterbridge. I had not realized there was a three-year gap between the writing of Two on a Tower and TMOC. I also had not realized that Hardy felt “a fit of depression” when TMOC was finished. Though that does not surprise me. Not just Hardy, but for any author, creating a novel must be an all consuming feat, and I can easily imagine a big hole of depression left when the writing is done.

Here are some of my favorite moments in this chapter.

First, I loved Virginia Woolf’s description of Max Gate in 1923, when she visited:

”with rolling massive downs, crowned with little tree coronets before and behind”

I’ve not been to Max Gate, but I can imagine how the roads and concrete must have built up around it, so that today it no longer looks like open land with wide views. You can tell just by looking at a map, the freeways lead almost to the front door. https://www.bing.com/maps?q=max+gate&...

I also loved reading about Tom planting “an infant forest”, on the land. How sad that Florence cut the trees down after he died. I wonder why? Were the trees infested, or blighted? Or was growth and progress responsible? I feel sad that they are no longer there to visit.

And how about all the Roman ruins he found on his property. I think that experience shows up in his poetry later on. I’m thinking about “The Roman Road” poem. One of the things I love about Hardy is how he seems to have this vision of the past and present existing simultaneously. That comes out especially in his poetry. I wonder if moments like this (where he discovers centuries old graves as he is about to build his permanent home) are when he starts thinking about this theme.

And then there is the fact that he doesn’t tell Emma about the skeletons. He doesn’t want her to have negative (or more negative??) associations with their new home. It occurs to him they might be a “evil omen”. There I think we see some of the superstitions that Hardy will attribute to the laborers and country people of his novels. I think of the dairy maids’ superstitions in Tess of the D’Urbervilles. I think these beliefs are part of what makes Hardy a complex man. A “time torn” man. He’s got one foot in the old beliefs and one foot heading into the 20th century.

I was surprised to learn that in 1883 Tom and Emma made their first venture into “The Season” in London and would continue that for 25 years! I would have thought Hardy would prefer the beauty of summer in the countryside. But then, all the attention from the aristocracy fits with Hardy's personality as well. How interesting that he became good friends with Mrs. Jeune and especially her daughters. That must have eased the pain of being childless for him. But once again, how sad it was for Emma that she was not liked by this family.

2003 Film with Ciaran Hinds as Henchard

The year is 1883. Tom and Emma are renting a house in Dorchester. The land (an acre and a half) for Max Gate has been purchased. House plans are being drawn up, and the Hardy family will build it. Tom and Emma become fixtures in their little corner of Dorchester. Tom is a Justice of the Peace, and a sought after celebrity. Emma’s life is more solitary, I would even say uninteresting. She goes to church, she corresponds with friends, but there is no nest of family to which she belongs. She has no work to do. They aren’t travelling anymore. Therein come the “conformers” of the title. I think of it more like complacency. It reminds me of our feeling today that the suburbs are boring, that nothing happens there.

I thought this chapter would mostly be about the building of Max Gate, really this chapter is about the writing of The Mayor of Casterbridge. I had not realized there was a three-year gap between the writing of Two on a Tower and TMOC. I also had not realized that Hardy felt “a fit of depression” when TMOC was finished. Though that does not surprise me. Not just Hardy, but for any author, creating a novel must be an all consuming feat, and I can easily imagine a big hole of depression left when the writing is done.

Here are some of my favorite moments in this chapter.

First, I loved Virginia Woolf’s description of Max Gate in 1923, when she visited:

”with rolling massive downs, crowned with little tree coronets before and behind”

I’ve not been to Max Gate, but I can imagine how the roads and concrete must have built up around it, so that today it no longer looks like open land with wide views. You can tell just by looking at a map, the freeways lead almost to the front door. https://www.bing.com/maps?q=max+gate&...

I also loved reading about Tom planting “an infant forest”, on the land. How sad that Florence cut the trees down after he died. I wonder why? Were the trees infested, or blighted? Or was growth and progress responsible? I feel sad that they are no longer there to visit.

And how about all the Roman ruins he found on his property. I think that experience shows up in his poetry later on. I’m thinking about “The Roman Road” poem. One of the things I love about Hardy is how he seems to have this vision of the past and present existing simultaneously. That comes out especially in his poetry. I wonder if moments like this (where he discovers centuries old graves as he is about to build his permanent home) are when he starts thinking about this theme.

And then there is the fact that he doesn’t tell Emma about the skeletons. He doesn’t want her to have negative (or more negative??) associations with their new home. It occurs to him they might be a “evil omen”. There I think we see some of the superstitions that Hardy will attribute to the laborers and country people of his novels. I think of the dairy maids’ superstitions in Tess of the D’Urbervilles. I think these beliefs are part of what makes Hardy a complex man. A “time torn” man. He’s got one foot in the old beliefs and one foot heading into the 20th century.

I was surprised to learn that in 1883 Tom and Emma made their first venture into “The Season” in London and would continue that for 25 years! I would have thought Hardy would prefer the beauty of summer in the countryside. But then, all the attention from the aristocracy fits with Hardy's personality as well. How interesting that he became good friends with Mrs. Jeune and especially her daughters. That must have eased the pain of being childless for him. But once again, how sad it was for Emma that she was not liked by this family.

Brian E wrote: " I consider A Laodicean to also be like a sensation novel. It involves a woman inheriting a medieval castle and uses plot devices such as falsified telegrams and faked photographs that are atypical for Hardy but typical for sensation fiction..."

I've never read A Laodician: A Story of Today ... I think the title probably scared me off! But now you describe it, Brian I really want to read it LOL!

I've never read A Laodician: A Story of Today ... I think the title probably scared me off! But now you describe it, Brian I really want to read it LOL!

Bridget - You've created a fantastic thread here, with so many tempting extras to read. I haven't a hope of "catching up", so am glad you say to join in any time. Perhaps I can have my own leisurely read to overlap and enjoy the comments here, starting next month 😊

Bionic Jean wrote: "Bridget - You've created a fantastic thread here, with so many tempting extras to read. I haven't a hope of "catching up", so am glad you say to join in any time. Perhaps I can have my own leisurel..."

Hi Jean! So nice to see your name pop up on this thread :-) Join us whenever you can. You already know so much about Hardy's biography you can easily come in and comment as you like.

Same for everyone really. You don't have to be reading along. If you find a moment of Hardy's life compelling, please feel free to add your thoughts. I didn't know that much about Tom and Emma Hardy. I'm learning so much, and its enriching my thoughts about his poetry and prose.

Hi Jean! So nice to see your name pop up on this thread :-) Join us whenever you can. You already know so much about Hardy's biography you can easily come in and comment as you like.

Same for everyone really. You don't have to be reading along. If you find a moment of Hardy's life compelling, please feel free to add your thoughts. I didn't know that much about Tom and Emma Hardy. I'm learning so much, and its enriching my thoughts about his poetry and prose.

Chapter 15: The Blighted Star

Ah, finally we arrive at the writing of Tess of the D’Urbervilles – which is my favorite Hardy novel, and actually one of my favorite novels ever. I’ve read it twice. I will likely read it again. I find more things to love about it with every read. Admittedly, I always find myself frustrated with the preposterous amount of bad luck that befalls Tess. Of course, this fits with Hardy’s suggestion at the end of the novel that The President of the Immortals was sporting with her all along (and by inference with all of us).

So, I love this line by Tomalin ”there are other examples in his fiction of people suffering from exceptionally bad luck . . . it looks as though it has been willed, by the gods, or fate, or possibly by the author”. . I share that same sentiment!

But, this chapter doesn’t start with Tess. My exuberance over Tess has caused me to jump ahead. The chapter starts in 1885. Tom and Emma are now living in Max Gate, though this chapter doesn’t talk much about the house itself. Instead, this chapter is more about Hardy’s internal thoughts and personal philosophy and how that affects his writing of The Woodlanders (1885), and Tess (1889-91).

Interestingly, Hardy says that The Woodlanders is the favorite of his novels, simply because he likes the story. I kind of love that. I haven’t read TW yet, but now I’m looking forward to it.

Tomalin then dives into more potential causes for the darkness in Hardy’s novels. She tells us he read philosophers like Schopenhauer. More importantly, she talks about his break with his Christian faith. We’ve already glimpsed some of this in Hardy’s younger days as his imagination and intellect tried to make sense of the sermons he heard from the pulpit; and left him with more questions than answers.

Yet, Hardy never completely broke with this Christian faith. He retained some of the Christian ideals of “do unto others” and “helping your neighbor”. We see some of that in his writing - where the farm laborers and country people help each other.

But he lost the key part of faith, which is the belief in a benevolent God who looks out for humankind. Instead, he seems to cling to the idea of an omniscient someone (or something) who doesn’t look out for anyone. That’s a bleak place to be. It doesn’t leave room for a humanist philosophy, where people look out for each other, because there is still the “immortal” playing sport with us all.

I found the details about the publishing of Tess fascinating. Unlike other novels, where Hardy had deadline pressure, he now has enough money to write at his own pace. How clever of him to publish Tess in magazines first, taking out the controversial parts (like the baby christening). And then to put them all back in and publish the book as he wanted. It makes me wonder if some of his other novels (Two on a Tower for example) might have been masterpieces if he had only spent more time revising them.

Ah, finally we arrive at the writing of Tess of the D’Urbervilles – which is my favorite Hardy novel, and actually one of my favorite novels ever. I’ve read it twice. I will likely read it again. I find more things to love about it with every read. Admittedly, I always find myself frustrated with the preposterous amount of bad luck that befalls Tess. Of course, this fits with Hardy’s suggestion at the end of the novel that The President of the Immortals was sporting with her all along (and by inference with all of us).

So, I love this line by Tomalin ”there are other examples in his fiction of people suffering from exceptionally bad luck . . . it looks as though it has been willed, by the gods, or fate, or possibly by the author”. . I share that same sentiment!

But, this chapter doesn’t start with Tess. My exuberance over Tess has caused me to jump ahead. The chapter starts in 1885. Tom and Emma are now living in Max Gate, though this chapter doesn’t talk much about the house itself. Instead, this chapter is more about Hardy’s internal thoughts and personal philosophy and how that affects his writing of The Woodlanders (1885), and Tess (1889-91).

Interestingly, Hardy says that The Woodlanders is the favorite of his novels, simply because he likes the story. I kind of love that. I haven’t read TW yet, but now I’m looking forward to it.

Tomalin then dives into more potential causes for the darkness in Hardy’s novels. She tells us he read philosophers like Schopenhauer. More importantly, she talks about his break with his Christian faith. We’ve already glimpsed some of this in Hardy’s younger days as his imagination and intellect tried to make sense of the sermons he heard from the pulpit; and left him with more questions than answers.

Yet, Hardy never completely broke with this Christian faith. He retained some of the Christian ideals of “do unto others” and “helping your neighbor”. We see some of that in his writing - where the farm laborers and country people help each other.

But he lost the key part of faith, which is the belief in a benevolent God who looks out for humankind. Instead, he seems to cling to the idea of an omniscient someone (or something) who doesn’t look out for anyone. That’s a bleak place to be. It doesn’t leave room for a humanist philosophy, where people look out for each other, because there is still the “immortal” playing sport with us all.

I found the details about the publishing of Tess fascinating. Unlike other novels, where Hardy had deadline pressure, he now has enough money to write at his own pace. How clever of him to publish Tess in magazines first, taking out the controversial parts (like the baby christening). And then to put them all back in and publish the book as he wanted. It makes me wonder if some of his other novels (Two on a Tower for example) might have been masterpieces if he had only spent more time revising them.

That's an interesting thought Bridget! (Tess is a favourite of mine too, as you'll have gathered. I first read it at 17.)

It's interesting how Claire Tomalin chronicles Thomas Hardy's religious doubts, nailing them to a particular period. Thank you for highlighting that it was nor so much a loss of Faith, as an adjustment in his beliefs. I think people can tend to oversimplify it, but you have expressed it so well 😊

It's interesting how Claire Tomalin chronicles Thomas Hardy's religious doubts, nailing them to a particular period. Thank you for highlighting that it was nor so much a loss of Faith, as an adjustment in his beliefs. I think people can tend to oversimplify it, but you have expressed it so well 😊

So sorry I'm behind. I'll catch up later in the week. I'm still busy on a work project, and don't pick this up often. I'm reading each chapter much more thoroughly that I normally do, which also slows me down. I'm taking notes and checking things out while I read.

So sorry I'm behind. I'll catch up later in the week. I'm still busy on a work project, and don't pick this up often. I'm reading each chapter much more thoroughly that I normally do, which also slows me down. I'm taking notes and checking things out while I read.But It also is making this 'slow read' a very enriching and rewarding reading experience. I'll post my Chapter 14 review shortly.

Chapter 14: Conformist Comments

Chapter 14: Conformist Comments1. THE SUCCCESFUL LIFE

The overriding atmosphere in this chapter is about Tom living as a relatively successful author. Tomalin starts off the chapter describing Tom’s return to Dorchester as taking responsibilities ‘as a prosperous citizen’ and even assuming his duties as a Justice of the Peace. Here are some aspects of his successful life I thought interesting:

a. Max Gate

I probably most enjoyed getting the information about Max Gate, especially that

- ‘Architect’ Tom designed it and had his father and brother as builders;

- It was more solidly functional with no running water but a flush toilet and ‘not beautiful’ with an ‘ungainly exterior.’

- The name comes from a nearby abandoned toll gate called Mack’s Gate. I disagree that the name has ‘nothing of the primitive rustic life’ in it. Max Gate had a hard sound to my ears that could evoke either primitive rustic or harshly urban settings.

- He created his own forest, planted the trees and loved it. It saddens me, no angers me that Florence removed the forest after Tom died. Once again, what a b|+#% !!!

b. The ‘Season’ in London

Interesting that for 25 years Tom and Emma lived in London for June and July and that:

- He liked to hob-nob with the upper crust and enjoyed a patron-like friendship with a wealthy socialite named Mrs. Jeune that Edith Wharton would have except that, unlike Tom, Wharton was also independently wealthy.

- They stayed in a nice hotel, the Saville, and had a nice discussion with William Dean Howells, the dean of American realist movement, at a party at the Saville;

2. TOM & EMMA MARRIAGE

Despite the successful atmosphere, this was sadly still a period without much marital bliss from Tom and Emma, even without much in difficulties, strife or avoidance issues. There are two Tomalin quotes that struck me:

- “To find that Emma’s zest for life, so much prized by him during their wooing, was not so attractive to others, that her charm fell flat was upsetting,” as Tomalin points out because Emma’s charms fell flat as her looks faded, she got heavier and her ‘once delightful’ talk that ‘strayed from the point’ was now ‘disconcerting.’

- That Mrs. Jeune’s two daughters who became lifelong family-like friends with their “Uncle’ Tom, disliked Emma.

3. THE CONFORMERS

- I enjoyed Tomalin’s ending that brought everything full circle, summing up the chapter’s theme as reflected in the title, with a depiction of Tom spending time in his Justice of Peace duties and even occasionally accompanying his ‘regular churchgoer’ wife at church as they become a ‘worthy pair of conformers.

Bionic Jean wrote: "That's an interesting thought Bridget! (Tess is a favourite of mine too, as you'll have gathered. I first read it at 17.)

It's interesting how Claire Tomalin chronicles [author:Tho..."

Hi Jean! So glad you commented, always nice to see your name pop up. Indeed, I remember Tess is a favorite of yours as well. How could it not be a favorite? Well, at least that's our opinion on the matter. ;-)

Thank you for liking my comments about Hardy's religious views. This book is truly deepening my thoughts about Hardy, particularly his religious/philosophical views. I'm so happy to be reading it.

It's interesting how Claire Tomalin chronicles [author:Tho..."

Hi Jean! So glad you commented, always nice to see your name pop up. Indeed, I remember Tess is a favorite of yours as well. How could it not be a favorite? Well, at least that's our opinion on the matter. ;-)

Thank you for liking my comments about Hardy's religious views. This book is truly deepening my thoughts about Hardy, particularly his religious/philosophical views. I'm so happy to be reading it.

Brian E wrote: "Chapter 14: Conformist Comments

1. THE SUCCCESFUL LIFE

The overriding atmosphere in this chapter is about Tom living as a relatively successful author. Tomalin starts off the chapter describing ..."

Oh the trees!! I know that was heart-breaking for me. I don't know anything about Florence (yet) - other than she cut down these trees, so my opinion of her is starting out quite low!

Also, I completely agree with you about the name "Max Gate". I think it has a lovely rustic sound to it. Sharp, crisp, to the point, not fancy at all. I think that suits the Hardys. I'm so glad you wrote the story of how it got named in your comments. So later on, when I only vaguely remember that story, I can find it again in this thread!

1. THE SUCCCESFUL LIFE

The overriding atmosphere in this chapter is about Tom living as a relatively successful author. Tomalin starts off the chapter describing ..."

Oh the trees!! I know that was heart-breaking for me. I don't know anything about Florence (yet) - other than she cut down these trees, so my opinion of her is starting out quite low!

Also, I completely agree with you about the name "Max Gate". I think it has a lovely rustic sound to it. Sharp, crisp, to the point, not fancy at all. I think that suits the Hardys. I'm so glad you wrote the story of how it got named in your comments. So later on, when I only vaguely remember that story, I can find it again in this thread!

Chapter 16: Tom and Em

This chapter, as the title, is all about the Hardy marriage. As we’ve seen before, the Hardys are settled into the community at Max Gate. Tom is a Justice of the Peace. Emma is an active member of the church. (Which could itself be a dividing issue for the couple. We’ve already seen Tom’s relationship to the church is complicated). By the time we reach the 1890s, Tom is still affectionate to Emma, at least in his letters to her, but he is more openly flirting with younger women.

But we haven’t yet reached the great rupture in their relationship where Emma basically locks herself in the attic. In this chapter, we see Tom and Emma using some of their newfound wealth from “Tess” to go to Italy. It’s an ambitious trip. They visit Rome, Florence, Venice and Milan. Emma writes wonderful descriptions in her diary. Tom writes wonderful poetry. I loved that they followed in the footsteps of Shelly and Keats. And that Henry James was making the same tour of Italy, at the same time, but in the opposite direction. It shows how important Hardy has become in the literary world, since he carries letters of introduction (from Robert Browning) to the same people H. James was meeting.

Back at home in Dorset, the problems of marriage loom larger. I find that in my own life. Holidays are lovely, but then you go home and face reality once again. Being left out of any mention of her contributions to Hardy’s writing is a deep wound for Emma. That wound becomes bigger when Hardy starts showing interest in other female writers.

Not that I think Emma is responsible for a major part of Tom’s novels. Yet, I’m certain she helped him – not just as a wife – but almost as a sort of secretary. Especially early on in his writing career – with "Far From the Madding Crowd". She copied pages for him. She talked with him, and he used her ideas. I loved Tomalin’s observation that it would have cost Tom very little to dedicate a book to Emma, and it would have made her so happy. But I understand given Tom’s own insecurity in his educational background, his lack of self-esteem, his class struggles – why he needed to take all the credit for himself. There was no ability on his part to share. Other than buying her houses and taking her on trips. And occasionally acknowledging a contribution she made.

And how about Robert Louis Stevenson’s wife Fanny, who had this to say after meeting Tom and Em. Tom was a ”quite pathetic figure, a pale, gentle, frightened little man, that one felt an instinctive tenderness for, with a wife . . . ugly is no word for it”!! I don’t know anything about Fanny Stevenson, but that is a pretty damning description of both Tom and Emma.

And then there is Rosamund Tomson, who Tom met at Lady Jeune’s house. She was a writer as well, and Hardy openly flirted with her in the summer of 1889. That can’t have been an easy thing to watch for Emma. It’s around this time that Emma starts writing in her diary about the disappointments and resentments in her marriage. Yet even until 1895, Tom was still writing to her calling her “my dearest” and saying he missed her when he was away. Marriage is a complicated thing, and one can never really know what goes on between spouses. But Tomalin is doing a decent job of painting a picture of what happened to Tom and Em.

This chapter, as the title, is all about the Hardy marriage. As we’ve seen before, the Hardys are settled into the community at Max Gate. Tom is a Justice of the Peace. Emma is an active member of the church. (Which could itself be a dividing issue for the couple. We’ve already seen Tom’s relationship to the church is complicated). By the time we reach the 1890s, Tom is still affectionate to Emma, at least in his letters to her, but he is more openly flirting with younger women.

But we haven’t yet reached the great rupture in their relationship where Emma basically locks herself in the attic. In this chapter, we see Tom and Emma using some of their newfound wealth from “Tess” to go to Italy. It’s an ambitious trip. They visit Rome, Florence, Venice and Milan. Emma writes wonderful descriptions in her diary. Tom writes wonderful poetry. I loved that they followed in the footsteps of Shelly and Keats. And that Henry James was making the same tour of Italy, at the same time, but in the opposite direction. It shows how important Hardy has become in the literary world, since he carries letters of introduction (from Robert Browning) to the same people H. James was meeting.

Back at home in Dorset, the problems of marriage loom larger. I find that in my own life. Holidays are lovely, but then you go home and face reality once again. Being left out of any mention of her contributions to Hardy’s writing is a deep wound for Emma. That wound becomes bigger when Hardy starts showing interest in other female writers.

Not that I think Emma is responsible for a major part of Tom’s novels. Yet, I’m certain she helped him – not just as a wife – but almost as a sort of secretary. Especially early on in his writing career – with "Far From the Madding Crowd". She copied pages for him. She talked with him, and he used her ideas. I loved Tomalin’s observation that it would have cost Tom very little to dedicate a book to Emma, and it would have made her so happy. But I understand given Tom’s own insecurity in his educational background, his lack of self-esteem, his class struggles – why he needed to take all the credit for himself. There was no ability on his part to share. Other than buying her houses and taking her on trips. And occasionally acknowledging a contribution she made.

And how about Robert Louis Stevenson’s wife Fanny, who had this to say after meeting Tom and Em. Tom was a ”quite pathetic figure, a pale, gentle, frightened little man, that one felt an instinctive tenderness for, with a wife . . . ugly is no word for it”!! I don’t know anything about Fanny Stevenson, but that is a pretty damning description of both Tom and Emma.

And then there is Rosamund Tomson, who Tom met at Lady Jeune’s house. She was a writer as well, and Hardy openly flirted with her in the summer of 1889. That can’t have been an easy thing to watch for Emma. It’s around this time that Emma starts writing in her diary about the disappointments and resentments in her marriage. Yet even until 1895, Tom was still writing to her calling her “my dearest” and saying he missed her when he was away. Marriage is a complicated thing, and one can never really know what goes on between spouses. But Tomalin is doing a decent job of painting a picture of what happened to Tom and Em.

You're doing a marvellous job bringing this all back to me Bridget!

I'm enjoying your insights as to their relationship. I remember thinking how sad it was that Emma felt obliged to stop her own creative endeavours. If she had not married, or had married differently, perhaps we would have seen more of her work. As you said "I understand given Tom’s own insecurity in his educational background, his lack of self-esteem, his class struggles – why he needed to take all the credit for himself" but it is still a minor tragedy. (I'd be anticipating if I said anything further, about his attitude, but the poems we've read about her reveal it.)

I'm enjoying your insights as to their relationship. I remember thinking how sad it was that Emma felt obliged to stop her own creative endeavours. If she had not married, or had married differently, perhaps we would have seen more of her work. As you said "I understand given Tom’s own insecurity in his educational background, his lack of self-esteem, his class struggles – why he needed to take all the credit for himself" but it is still a minor tragedy. (I'd be anticipating if I said anything further, about his attitude, but the poems we've read about her reveal it.)

Bionic Jean wrote: "You're doing a marvellous job bringing this all back to me Bridget!

I'm enjoying your insights as to their relationship. I remember thinking how sad it was that Emma felt obliged to stop her own ..."

Thank you Jean. I'm having a great time reading this book, and learning so much more about Hardy.

You are so right in saying "its a minor tragedy". It does feel that way as I'm reading about Tom and Emma's relationship.

I'm enjoying your insights as to their relationship. I remember thinking how sad it was that Emma felt obliged to stop her own ..."

Thank you Jean. I'm having a great time reading this book, and learning so much more about Hardy.

You are so right in saying "its a minor tragedy". It does feel that way as I'm reading about Tom and Emma's relationship.

Chapter 17: The Terra-Cotta Dress

A Thunderstorm In Town

She wore a 'terra-cotta' dress,

And we stayed, because of the pelting storm,

Within the hansom's dry recess,

Though the horse had stopped; yea, motionless

We sat on, snug and warm.

We have now arrived at the moment when Tom meets the lovely Florence Henniker. She is the woman in the “terra-cotta” dress in the the poem above. Tom and Emma travel to Dublin in 1893, where they stay with Lord Houghton and his sister, Florence Henniker. Florence, is an upper class woman. She is also a writer. It’s sort of the perfect storm to drive a wedge between Tom and Emma. Not only is Tom flirting with Mrs. Henniker, but he is also engaging with her as one writer to another, and for Emma that is perhaps the bigger betrayal.

Florence Henniker

But Mrs. Henniker does not return Tom’s advances. She is happy to remain friends with him, but nothing further happens. She did not want to cross the line established by the proprieties of church for a married woman. This roadblock presented by the church turns Tom farther away from religion.

I have to wonder, as well, if she just didn’t share the attraction to Tom that he felt for her. Though she was happy his attention boosted her writing career. Tom seems to revel in the attention, and though Tomalin doesn’t say this, it seems to me that Tom’s success has gone to his head. That he thinks very highly of himself, and in that way is pulling away from his life with Emma.

Around this time, Hardy starts writing Jude the Obscure. Its very telling that he hires Ms. Tigan as a typist rather than using Emma as he always had. He also collaborates with Mrs. Henniker, asking her opinion about female characters, instead of Emma. In fact, he doesn't show Emma a copy of "Jude" until it is published. There is clearly something wrong in the Hardy house.

The second half of this chapter is completely about the writing of “Jude” – and if you have not read it you might want to skip pages 254-256, as Tomalin spares no words in describing the horror the readers of “Jude” encounter.

Tomalin asserts that Hardy uses his own life for much of the characters and themes of “Jude”. On the one hand, it’s easy to see the parallels between Florence Henniker and Sue Bridehead, in that Florence was sexually unavailable to Hardy as was Sue to Jude. Even when Tomalin says Hardy is “reinventing his childhood only making it worse”, I can still believe her. But then she says

“this prompts the question as to whether he [Hardy] had only lately learnt the facts of his own conception and birth and become aware that he had been unwanted”

at that point Tomalin lost me. I’m certain all authors use events from their lives while writing, but I think they also invent characteristics and plot points for no other reason than their imaginations create them, and they make the stories better.

Of course I’ve not read Jude. So perhaps I’m way off here and Tomalin is correct. When I do eventually read Jude, I will make sure to come back to this chapter and re-read it to see if my opinions change. What is certain, is that after writing “Jude”, Hardy now had enough money to completely give up writing fiction to earn a living. And so, as we know, he devoted himself to poetry.

A Thunderstorm In Town

She wore a 'terra-cotta' dress,

And we stayed, because of the pelting storm,

Within the hansom's dry recess,

Though the horse had stopped; yea, motionless

We sat on, snug and warm.

We have now arrived at the moment when Tom meets the lovely Florence Henniker. She is the woman in the “terra-cotta” dress in the the poem above. Tom and Emma travel to Dublin in 1893, where they stay with Lord Houghton and his sister, Florence Henniker. Florence, is an upper class woman. She is also a writer. It’s sort of the perfect storm to drive a wedge between Tom and Emma. Not only is Tom flirting with Mrs. Henniker, but he is also engaging with her as one writer to another, and for Emma that is perhaps the bigger betrayal.

Florence Henniker

But Mrs. Henniker does not return Tom’s advances. She is happy to remain friends with him, but nothing further happens. She did not want to cross the line established by the proprieties of church for a married woman. This roadblock presented by the church turns Tom farther away from religion.

I have to wonder, as well, if she just didn’t share the attraction to Tom that he felt for her. Though she was happy his attention boosted her writing career. Tom seems to revel in the attention, and though Tomalin doesn’t say this, it seems to me that Tom’s success has gone to his head. That he thinks very highly of himself, and in that way is pulling away from his life with Emma.

Around this time, Hardy starts writing Jude the Obscure. Its very telling that he hires Ms. Tigan as a typist rather than using Emma as he always had. He also collaborates with Mrs. Henniker, asking her opinion about female characters, instead of Emma. In fact, he doesn't show Emma a copy of "Jude" until it is published. There is clearly something wrong in the Hardy house.

The second half of this chapter is completely about the writing of “Jude” – and if you have not read it you might want to skip pages 254-256, as Tomalin spares no words in describing the horror the readers of “Jude” encounter.

Tomalin asserts that Hardy uses his own life for much of the characters and themes of “Jude”. On the one hand, it’s easy to see the parallels between Florence Henniker and Sue Bridehead, in that Florence was sexually unavailable to Hardy as was Sue to Jude. Even when Tomalin says Hardy is “reinventing his childhood only making it worse”, I can still believe her. But then she says

“this prompts the question as to whether he [Hardy] had only lately learnt the facts of his own conception and birth and become aware that he had been unwanted”

at that point Tomalin lost me. I’m certain all authors use events from their lives while writing, but I think they also invent characteristics and plot points for no other reason than their imaginations create them, and they make the stories better.

Of course I’ve not read Jude. So perhaps I’m way off here and Tomalin is correct. When I do eventually read Jude, I will make sure to come back to this chapter and re-read it to see if my opinions change. What is certain, is that after writing “Jude”, Hardy now had enough money to completely give up writing fiction to earn a living. And so, as we know, he devoted himself to poetry.

Bridget wrote: "Chapter 17: The Terra-Cotta Dress

Bridget wrote: "Chapter 17: The Terra-Cotta DressBut then she says

“this prompts the question as to whether he [Hardy] had only lately learnt the facts of his own conception and birth and become aware that he had been unwanted”

at that point Tomalin lost me...."

Bridget, Hardy's mother was pregnant with Tom so his parents married. His mother had planned to move to a city and work in a restaurant/pub before she became pregnant. So she missed that opportunity and had to stay in the country. It does sound harsh for Tomalin to say that "he had been unwanted" since he seems to have been close to his parents and loved. "Unplanned" might have been a better word.

Chapter 15: The Blighted Star Comments

Chapter 15: The Blighted Star Comments1. TOM’s PERSONALITY

Tomalin had two insightful passages or anecdotes that I found interesting as indicating some aspects of Tom’s personality that we have come to understand:

a. In discussing how no one has yet adequately explained where Tom’s black view of life came from, Tomalin proffered this answer: “something in his constitution made him extraordinarily sensitive to humiliations, griefs and disappointments, and that the wounds they inflicted never healed but went on hurting him throughout his life.” This seems to be right to me, though I’m getting my info from the theory’s proponent.

b. After first expressing sympathy to his friend, fellow author Henry Rider Haggard, after the death of his 10-year old son, Hardy then wrote ”to be candid, I think the death of a child is never really to be regretted, when one reflects on what he has escaped.” I agree with Tomalin’s assessment of this as insensitive. You can say ‘he’s in a better place’ to get that idea of comfort, as that just promotes the joy of an afterlife, but you don’t trash the life the parents were able to provide the son here on earth and, most importantly, you don’t trash the parents grief by saying they shouldn’t regret their son’s death. While Hardy may have had his reasons for saying this, to me it is an indication of another trait Hardy seems to exhibit to me; a relative lack of social skills that makes his interpersonal relationships more difficult. If he intended to just give the Riders a life lecture, he’s tactless, clueless and /or heartless. If he honestly meant to say these words in comfort and, surprisingly in a gifted writer, fumbled the ball, then he is fairly inept at being a friend. I never imagined Haggard and Hardy as friends as they seem such different writers.

2. TWO NOVELS

Much of the section is about Tom’s writing two novels during this period from 1885 to 1891 and starting a third.

a. The Woodlanders

As I plan to re-read tis sometime in the future, I skimmed much of the details so not to get any reminders. I also have seen the movie version with Rufus Sewell and own the DVD. I remember liking it very much. The discussion of it did remind me that

- Two of my four favorite Hardy novels, The Woodlanders and The Return of the Native are the best representative of hardy setting novels in a single rustic area: Little Hincock woods of The Woodlanders and Egdon Heath of TROTN.

- In contrast, the other two of my four favorites, Tess and Jude have more varietal settings.

b. Tess

Not much to add to Bridget’s commentary, just two Tomalin quotes that struck me;

- On Hardy’s fondness for Tess, “he had lost his heart to Tess as he wrote about her.” I understand. I did too, reading about her.

- On how Hardy put Tess in various settings:

“so that she appeared at times an emblematic figure as she moves through the season of the year with their appropriate countryside activities, like a figure in a series of paintings.”

I agree with Connie, that "unplanned" is better than "unwanted". I think Claire Tomalin might have been allowing herself a little over-fanciful interpretation there.

Connie (on semi-hiatus) wrote: "Bridget wrote: "Chapter 17: The Terra-Cotta Dress

But then she says

“this prompts the question as to whether he [Hardy] had only lately learnt the facts of his own conception and birth and become a..."

Connie, it so good to see you here! Thank you for commenting. I agree "unplanned" is much better than "unwanted". That's a much more succinct way to say what I was getting at. Tom's parents appear to love him very much, he was never "unwanted". It's true his mother wasn't fond of marriage in general. I'm sure she had regrets, but not about having Tom, or his siblings.

Anyway, like Jean said, Tomalin is just a bit over-fanciful in this section. I think Tom used his life experiences in his work, but he also just made stuff up out of his imagination. Like any author I suppose.

But then she says

“this prompts the question as to whether he [Hardy] had only lately learnt the facts of his own conception and birth and become a..."

Connie, it so good to see you here! Thank you for commenting. I agree "unplanned" is much better than "unwanted". That's a much more succinct way to say what I was getting at. Tom's parents appear to love him very much, he was never "unwanted". It's true his mother wasn't fond of marriage in general. I'm sure she had regrets, but not about having Tom, or his siblings.

Anyway, like Jean said, Tomalin is just a bit over-fanciful in this section. I think Tom used his life experiences in his work, but he also just made stuff up out of his imagination. Like any author I suppose.

Brian E wrote: "Chapter 15: The Blighted Star Comments

1. TOM’s PERSONALITY

Tomalin had two insightful passages or anecdotes that I found interesting as indicating some aspects of Tom’s personality that we have..."

Wonderful comments Brian! Thank you. I particularly like the quote you picked where Tomalin discusses reasons for Tom's dark side. I liked that quote as well and agree with you that it rings very true. Like you said, we are getting that info from the proponent of the theory (Tomalin) and as we've discussed above she is not always correct in her postulations. So, it's good to remain skeptical, but she is on the whole, more right than wrong. At least in my opinion. It's a tricky business looking through someone's life and trying to draw conclusions.

1. TOM’s PERSONALITY

Tomalin had two insightful passages or anecdotes that I found interesting as indicating some aspects of Tom’s personality that we have..."

Wonderful comments Brian! Thank you. I particularly like the quote you picked where Tomalin discusses reasons for Tom's dark side. I liked that quote as well and agree with you that it rings very true. Like you said, we are getting that info from the proponent of the theory (Tomalin) and as we've discussed above she is not always correct in her postulations. So, it's good to remain skeptical, but she is on the whole, more right than wrong. At least in my opinion. It's a tricky business looking through someone's life and trying to draw conclusions.

Chapter 16: Tom and Em Comments

Chapter 16: Tom and Em CommentsThis Chapter covers more or less the same time frame as the prior chapter but focusing on the Tom and Emma relationship

1. ITALY TOUR

Tomalin gave a good overview of the six week tour they had in 1885. A few items that struck me:

a. It pleases me that they are able to enjoy themselves when on holiday – that they travel well together. It means they get some happiness out of the relationship. Perhaps they get along best when Tom doesn’t worry about what others are thinking about Emma and Emma has sightseeing to keep her interested.

b. Tomalin does bring up Henry James fairly often, two fairly non-comparable authors in characters, subjects and style. To me Hardy is warm and James is cool.

c. It was interesting that Hardy was such a Shelley fan. I know more about those poets Byron, Shelley & Keats than about their poetry. I’ll have to check him out sometime.

d. I liked Tomalin’s observation that in Genoa Hardy noticed the “marble palaces and the washing lines” while Emma noticed the colors “...yellow, salmon.” Different interests that at least they were both able to pursue

2. MISCELLANEOUS

a. Tess