Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit: Chapters 1 - 11

message 51:

by

Luffy Sempai

(new)

Sep 14, 2020 11:35AM

I learned a new word; discursive. Very precise definition indeed.

I learned a new word; discursive. Very precise definition indeed.

reply

|

flag

message 52:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 14, 2020 12:59PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

One interesting comment worth mentioning from Charles Dickens's "Preface" to the 1857 edition of Little Dorrit, is:

"In the Preface to Bleak House I remarked that I had never had so many readers. In the Preface to its next successor, Little Dorrit, I have still to repeat the same words."

This is good, isn't it? Makes us feel that his readers of the time really enjoyed it :) There's just one problem:

Little Dorrit isn't the "next successor" to Bleak House. Hard Times comes between them!

Now it's very unlikely that Charles Dickens forgot the order his novels were published in, so what can he have meant? Did he not count Hard Times, because it was a shorter book than either of the others?

It seems very odd!

"In the Preface to Bleak House I remarked that I had never had so many readers. In the Preface to its next successor, Little Dorrit, I have still to repeat the same words."

This is good, isn't it? Makes us feel that his readers of the time really enjoyed it :) There's just one problem:

Little Dorrit isn't the "next successor" to Bleak House. Hard Times comes between them!

Now it's very unlikely that Charles Dickens forgot the order his novels were published in, so what can he have meant? Did he not count Hard Times, because it was a shorter book than either of the others?

It seems very odd!

I hope to join in on this read but I may be a little late as I've got so many books going at the moment! 😄

I hope to join in on this read but I may be a little late as I've got so many books going at the moment! 😄

Bionic Jean wrote: "Ooo I hope those notes are good! But you have to be careful not to read things too soon ... I never read prefaces etc., until the end! Does anyone else feel like that?"

Bionic Jean wrote: "Ooo I hope those notes are good! But you have to be careful not to read things too soon ... I never read prefaces etc., until the end! Does anyone else feel like that?"Jean- I learned the hard way reading introductions. I agree with you- I just start reading from Chapter 1. The good thing about my book, here - it warns me Not to read the Introduction. I like that!

message 56:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 14, 2020 02:13PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Meg - I'm delighted you will join in too, when you are able to :)

Martha - I agree, that is a very good thing! Now if only the same comment could be a prefixed to some blurbs ...

Martha - I agree, that is a very good thing! Now if only the same comment could be a prefixed to some blurbs ...

I don't know why he would omit Hard Times maybe he felt the same way I do about it? Or maybe you are right, Jean, short (for Dickens) as it is he probably thought of it as a novella or maybe even an essay!

I don't know why he would omit Hard Times maybe he felt the same way I do about it? Or maybe you are right, Jean, short (for Dickens) as it is he probably thought of it as a novella or maybe even an essay!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy wrote: "why do many people don't like Dickens? ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Luffy wrote: "why do many people don't like Dickens? ..."I'm tempted to say I have no idea! But I do have a few:

1. They may have been force-fed Charles Dickens, or been badly ta..."

Another thing that I think is difficult is to understand the thinking of people from a different time and what would influence them to act in a certain way. Ideas and customs change so much over time. You touch on this with your comment about Dickens idea of the "ideal woman". Even as late as the 1950s and 1960s that ideal was a lot different than it is today. For a class I took in women's history we read an article from the 1950s about how to be an ideal wife. The article would cause a major uproar if it was written today in the US.

This might be my favorite novel by Dickens next to Bleak House. I'll try to chime in if I can find my copy which I have around this house someplace.

This might be my favorite novel by Dickens next to Bleak House. I'll try to chime in if I can find my copy which I have around this house someplace.

It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that it’s slow and in depth, so not to everyone’s liking. I am also reading War and Peace and while I like it, it’s not the same experience as Dickens. I enjoyed Anna Karenina more, so it’s not just a Tolstoy’s writing, but it does help me see how some people would not find Dickens as smooth and easy to read as I do. It’s just my cup of tea whereas other authors are a little more work to read.

It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that it’s slow and in depth, so not to everyone’s liking. I am also reading War and Peace and while I like it, it’s not the same experience as Dickens. I enjoyed Anna Karenina more, so it’s not just a Tolstoy’s writing, but it does help me see how some people would not find Dickens as smooth and easy to read as I do. It’s just my cup of tea whereas other authors are a little more work to read.

I like the humanitarian values in his books. That was topic of my seminar in post graduation. The first book I read was A Tale of Two Cities and it’s my all time favourite. And his descriptions ... the opening scene of Martin Chuzzwit .... it is something Tolstoy lacks. Tolstoy is great in his own way, but Dickens is Dickens 😀

I like the humanitarian values in his books. That was topic of my seminar in post graduation. The first book I read was A Tale of Two Cities and it’s my all time favourite. And his descriptions ... the opening scene of Martin Chuzzwit .... it is something Tolstoy lacks. Tolstoy is great in his own way, but Dickens is Dickens 😀

Some people who say they don’t like Dickens do read fantasy books where there is lots of description and specialized vocabulary. This is called “world building”. Readers are expected to accept the values of that world, the style of speech, etc. Well, with Dickens, we are entering his world. Our rules of language, causality, and behavior don’t necessarily apply. That’s part of the pleasure of reading, for me.

Some people who say they don’t like Dickens do read fantasy books where there is lots of description and specialized vocabulary. This is called “world building”. Readers are expected to accept the values of that world, the style of speech, etc. Well, with Dickens, we are entering his world. Our rules of language, causality, and behavior don’t necessarily apply. That’s part of the pleasure of reading, for me.

I like historical fiction so A Tale of Two Cities is a favourite. And I hope someday I will love the made up worlds also.

I like historical fiction so A Tale of Two Cities is a favourite. And I hope someday I will love the made up worlds also.

Robin P wrote: "Some people who say they don’t like Dickens do read fantasy books where there is lots of description and specialized vocabulary. This is called “world building”. Readers are expected to accept the ..."

Robin P wrote: "Some people who say they don’t like Dickens do read fantasy books where there is lots of description and specialized vocabulary. This is called “world building”. Readers are expected to accept the ..."Speaking as a Dickens skeptic, I think that what frustrates me as a reader is that he was quite capable of writing in a fast, modern way. But then he invariably goes back to his ponderous style. It's as if the Greeks had discovered the decimal system and then thrown it away for their archaic maths.

message 65:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 03:37AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Thank you all ... Katy, Nidhi, Ashley and Robin, for these insightful comments :)

Franky - we're delighted to have you with us, right at the start of this novel, especially since it's one of your favourites :)

Luffy - I have just realised that your self-chosen place in this group is to be devil's advocate ... I'm not really sure many will agree with you here, but that's fine! Perhaps we'll convert you yet, and you'll be a Dickens enthusiast ;)

So without more ado, we'll now begin our read of Little Dorrit. Interestingly, the original title Charles Dickens selected for this one was "Nobody's Fault", which I actually prefer. It has two meanings, as one of the characters is sometimes referred to as "Nobody".

But let's get on to the text itself.

The first chapter of a novel by Charles Dickens can seem a bit wordy, if you're unused to reading Victorian novels, or if English isn't your first language. This is why I write a full summary of each chapter every day.

Please though, feel free to skip these if the chapter is fresh in your mind. They are neutral, and as objective as possible, with no interpretation (apart from what I have selected as important, of course).

Franky - we're delighted to have you with us, right at the start of this novel, especially since it's one of your favourites :)

Luffy - I have just realised that your self-chosen place in this group is to be devil's advocate ... I'm not really sure many will agree with you here, but that's fine! Perhaps we'll convert you yet, and you'll be a Dickens enthusiast ;)

So without more ado, we'll now begin our read of Little Dorrit. Interestingly, the original title Charles Dickens selected for this one was "Nobody's Fault", which I actually prefer. It has two meanings, as one of the characters is sometimes referred to as "Nobody".

But let's get on to the text itself.

The first chapter of a novel by Charles Dickens can seem a bit wordy, if you're unused to reading Victorian novels, or if English isn't your first language. This is why I write a full summary of each chapter every day.

Please though, feel free to skip these if the chapter is fresh in your mind. They are neutral, and as objective as possible, with no interpretation (apart from what I have selected as important, of course).

message 66:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 03:38AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

LITTLE DORRIT

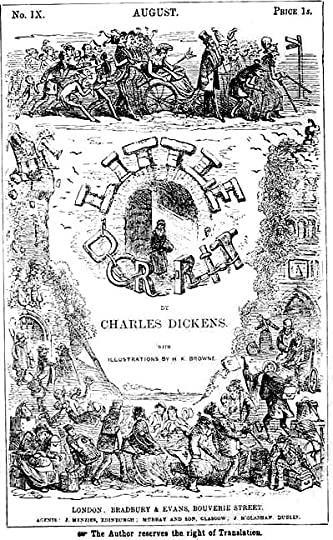

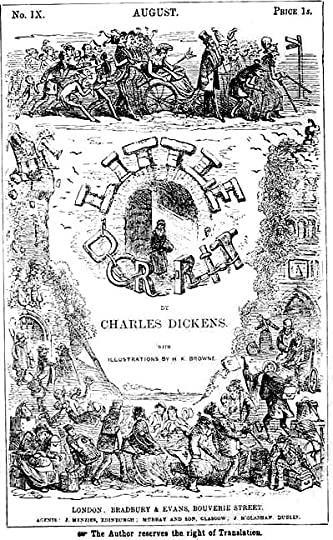

A monthly "wrapper" (cover) by Phiz

BOOK 1 - POVERTY

Chapter 1:

The story begins in Marseilles, a city on the Mediterranean coast of France, where it is blisteringly hot. The sun glares and scorches, and “something quivered in the atmosphere, as if the air itself were panting”:

“Everything in Marseilles, and about Marseilles, had stared at the fervid sky, and been stared at in return, until a staring habit had become universal there. Strangers were stared out of countenance by staring white houses, staring white walls, staring white streets, staring tracts of arid road, staring hills from which verdure was burnt away. The only things to be seen not fixedly staring and glaring were the vines drooping under their load of grapes. These did occasionally wink a little, as the hot air barely moved their faint leaves.”

There is a lengthy description of the white-hot Marseilles, as it “lay broiling in the sun one day”, thirty years earlier. That makes the time when the novel is set, about 1826.

We move in contrast to a “villainous prison”, and a gloomy cell with two inmates.

The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men were all deteriorated by confinement. As the captive men were faded and haggard, so the iron was rusty, the stone was slimy, the wood was rotten, the air was faint, the light was dim. Like a well, like a vault, like a tomb, the prison had no knowledge of the brightness outside“

One of the prisoners is leaning against the bars, waiting impatiently for food. The other man is lying on the stone floor. He has no great cloak like the first but is covered with a coarse brown coat. He is a Frenchman called Jean-Baptiste Cavalletto, and his imperious master, to whom he is very submissive, is Monsieur Rigaud, whose:

“eyes, too close together, were not so nobly set in his head as those of the king of beasts are in his, and they were sharp rather than bright … They had no depth or change; they glittered, and they opened and shut … He had a hook nose, handsome after its kind, but too high between the eyes … For the rest, he was large and tall in frame, had thin lips, where his thick moustache showed them at all, and a quantity of dry hair, of no definable colour, in its shaggy state, but shot with red. The hand with which he held the grating (seamed all over the back with ugly scratches newly healed), was unusually small and plump; would have been unusually white but for the prison grime.”

This unprepossessing man also had one unusual distinguishing characteristic:

“When Monsieur Rigaud laughed, a change took place in his face, that was more remarkable than prepossessing. His moustache went up under his nose, and his nose came down over his moustache, in a very sinister and cruel manner.”

In time, the prison-keeper appears carrying his daughter, who is three or four years old, and a basket of food. Oh, but what food it is! Just three hunks of coarse bread and sour drink for Jean-Baptiste, and all manner of delicious delicacies and fine wine for Monsieur Rigaud. The jailer refers to the prisoners as his “little birds” and invited his daughter to feed them, commenting on the difference in their food. The little girl is happy to pass food to Jean-Baptiste. Even though his hands are so rough and scaly, he has:

“a lively look … sunburnt, quick, lithe, little man, though rather thickset. Earrings in his brown ears, white teeth lighting up his grotesque brown face, intensely black hair clustering about his brown throat, a ragged red shirt open at his brown breast. Loose, seaman-like trousers, decent shoes, a long red cap, a red sash round his waist, and a knife in it”

but when the little girl looks at Monsieur Rigaud, her “expression [is] half of fright and half of anger.”

Monsieur Rigaud asks the jailer if there is any news, and is told that he is to be tried by the President that very day, at one o’clock.

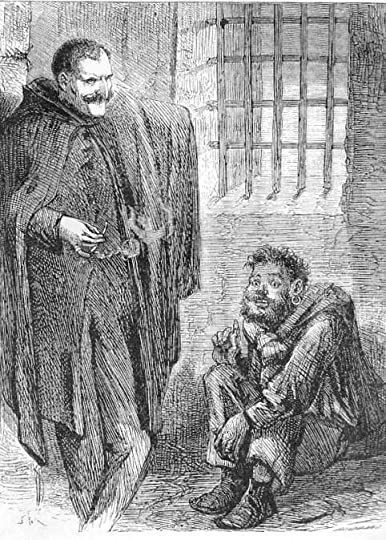

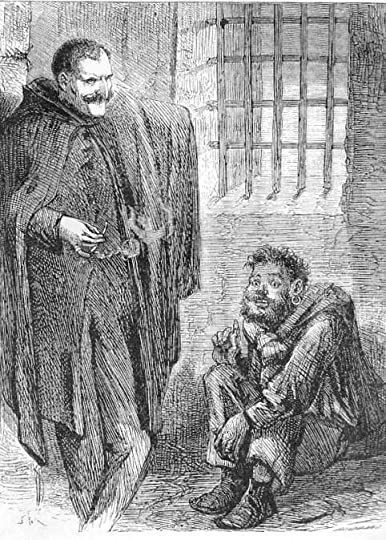

Rigaud and Cavalletto - Sol Etinge Jr. 1871

After the prison-keeper has left, Rigaud goes over what he is going to say in his defence. We learn that Jean-Baptiste has been imprisoned for dealing in contraband goods, and having wrong identification papers, Rigaud’s crime is more serious.

Rigaud is about thirty-five years of age:

“He had a certain air of being a handsome man—which he was not; and a certain air of being a well-bred man—which he was not. It was mere swagger and challenge; but in this particular, as in many others, blustering assertion goes for proof, half over the world.”

He tells how he came to be there, stressing that he is a gentleman, who has never demeaned himself by working:

“I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss—Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world.”

Rigaud had come to Marseilles about two years before, and stayed with a Monsieur Henri Barronneau, who was sixty-five or more, and his wife of just twenty-two. Monsieur Barronneau was in ill health, and died:

“not a rare misfortune, that. It happens without any aid of mine, pretty often”

and Rigaud married the willing young widow, who had been left all her husband’s property. He hoped to be able to govern her finances:

“I am proud … I can’t submit; I must govern”

But his new wife’s relatives objected. Rigaud also began to find his wife “a little vulgar”, and she resisted his efforts to ”improve her manners:

“I may have been seen to slap her face …”

One night Rigaud and his wife were walking “amicably” on a cliff-top, when his wife began to talk about and defend her relations. Rigaud maintained that she attacked him “with screams of passion” and eventually threw herself off the cliffs. He said the truth had been perverted so that he was now accused of assassinating his wife.

The chapter ends with Jean-Baptise left in the cell, as the baying of crowds is heard outside:

“clasping the grate with both hands, an uproar broke upon his hearing; yells, shrieks, oaths, threats, execrations, all comprehended in it, though (as in a storm) nothing but a raging swell of sound distinctly heard

and several guards accompany Rigaud to his hearing in front of the President:

“There is no sort of whiteness in all the hues under the sun at all like the whiteness of Monsieur Rigaud’s face as it was then.”

A monthly "wrapper" (cover) by Phiz

BOOK 1 - POVERTY

Chapter 1:

The story begins in Marseilles, a city on the Mediterranean coast of France, where it is blisteringly hot. The sun glares and scorches, and “something quivered in the atmosphere, as if the air itself were panting”:

“Everything in Marseilles, and about Marseilles, had stared at the fervid sky, and been stared at in return, until a staring habit had become universal there. Strangers were stared out of countenance by staring white houses, staring white walls, staring white streets, staring tracts of arid road, staring hills from which verdure was burnt away. The only things to be seen not fixedly staring and glaring were the vines drooping under their load of grapes. These did occasionally wink a little, as the hot air barely moved their faint leaves.”

There is a lengthy description of the white-hot Marseilles, as it “lay broiling in the sun one day”, thirty years earlier. That makes the time when the novel is set, about 1826.

We move in contrast to a “villainous prison”, and a gloomy cell with two inmates.

The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men were all deteriorated by confinement. As the captive men were faded and haggard, so the iron was rusty, the stone was slimy, the wood was rotten, the air was faint, the light was dim. Like a well, like a vault, like a tomb, the prison had no knowledge of the brightness outside“

One of the prisoners is leaning against the bars, waiting impatiently for food. The other man is lying on the stone floor. He has no great cloak like the first but is covered with a coarse brown coat. He is a Frenchman called Jean-Baptiste Cavalletto, and his imperious master, to whom he is very submissive, is Monsieur Rigaud, whose:

“eyes, too close together, were not so nobly set in his head as those of the king of beasts are in his, and they were sharp rather than bright … They had no depth or change; they glittered, and they opened and shut … He had a hook nose, handsome after its kind, but too high between the eyes … For the rest, he was large and tall in frame, had thin lips, where his thick moustache showed them at all, and a quantity of dry hair, of no definable colour, in its shaggy state, but shot with red. The hand with which he held the grating (seamed all over the back with ugly scratches newly healed), was unusually small and plump; would have been unusually white but for the prison grime.”

This unprepossessing man also had one unusual distinguishing characteristic:

“When Monsieur Rigaud laughed, a change took place in his face, that was more remarkable than prepossessing. His moustache went up under his nose, and his nose came down over his moustache, in a very sinister and cruel manner.”

In time, the prison-keeper appears carrying his daughter, who is three or four years old, and a basket of food. Oh, but what food it is! Just three hunks of coarse bread and sour drink for Jean-Baptiste, and all manner of delicious delicacies and fine wine for Monsieur Rigaud. The jailer refers to the prisoners as his “little birds” and invited his daughter to feed them, commenting on the difference in their food. The little girl is happy to pass food to Jean-Baptiste. Even though his hands are so rough and scaly, he has:

“a lively look … sunburnt, quick, lithe, little man, though rather thickset. Earrings in his brown ears, white teeth lighting up his grotesque brown face, intensely black hair clustering about his brown throat, a ragged red shirt open at his brown breast. Loose, seaman-like trousers, decent shoes, a long red cap, a red sash round his waist, and a knife in it”

but when the little girl looks at Monsieur Rigaud, her “expression [is] half of fright and half of anger.”

Monsieur Rigaud asks the jailer if there is any news, and is told that he is to be tried by the President that very day, at one o’clock.

Rigaud and Cavalletto - Sol Etinge Jr. 1871

After the prison-keeper has left, Rigaud goes over what he is going to say in his defence. We learn that Jean-Baptiste has been imprisoned for dealing in contraband goods, and having wrong identification papers, Rigaud’s crime is more serious.

Rigaud is about thirty-five years of age:

“He had a certain air of being a handsome man—which he was not; and a certain air of being a well-bred man—which he was not. It was mere swagger and challenge; but in this particular, as in many others, blustering assertion goes for proof, half over the world.”

He tells how he came to be there, stressing that he is a gentleman, who has never demeaned himself by working:

“I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss—Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world.”

Rigaud had come to Marseilles about two years before, and stayed with a Monsieur Henri Barronneau, who was sixty-five or more, and his wife of just twenty-two. Monsieur Barronneau was in ill health, and died:

“not a rare misfortune, that. It happens without any aid of mine, pretty often”

and Rigaud married the willing young widow, who had been left all her husband’s property. He hoped to be able to govern her finances:

“I am proud … I can’t submit; I must govern”

But his new wife’s relatives objected. Rigaud also began to find his wife “a little vulgar”, and she resisted his efforts to ”improve her manners:

“I may have been seen to slap her face …”

One night Rigaud and his wife were walking “amicably” on a cliff-top, when his wife began to talk about and defend her relations. Rigaud maintained that she attacked him “with screams of passion” and eventually threw herself off the cliffs. He said the truth had been perverted so that he was now accused of assassinating his wife.

The chapter ends with Jean-Baptise left in the cell, as the baying of crowds is heard outside:

“clasping the grate with both hands, an uproar broke upon his hearing; yells, shrieks, oaths, threats, execrations, all comprehended in it, though (as in a storm) nothing but a raging swell of sound distinctly heard

and several guards accompany Rigaud to his hearing in front of the President:

“There is no sort of whiteness in all the hues under the sun at all like the whiteness of Monsieur Rigaud’s face as it was then.”

message 67:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 08:04AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

This is a long, powerful chapter to begin with, and if we know what is to come, we might think Marseilles is a strange place to start.

Charles Dickens seems to make a point of starting most of his novels with an unpleasant description—whether a “London particular”, a grimy city rooftop landscape or—as now—an unpleasant description of summer in the South of France, when the sun glares like a lidless, inhuman eye. Dickens is enjoying revelling in his prose again :)

“with people lounging and lying wherever shade was, with but little hum of tongues or barking of dogs, with occasional jangling of discordant church bells and rattling of vicious drums, Marseilles, a fact to be strongly smelt and tasted, lay broiling in the sun one day.”

And now we have a complete contrast! We feel the gloom and claustrophobia of what follows all the more for it. There is a little cell, inside “a villainous prison” which contains two prisoners. Cleverly, Dickens does not name these two until later.

I have the feeling that with this introductory chapter Dickens is setting the stage. And what a lot of foreshadowing there is to be sure!

The title “Sun and Shadow” is very clever. I love the description of the baking hot Marseilles, and the cold, dark, damp prison setting inside, which seems so much more gloomy after having been in the glaringly hot sun.

Also, I believe the description of Rigaud suggests that the shadow is not just literal. He seems such a villain. So I’m wondering which of these is going to be a metaphor for the novel: optimism and sunlight? Or gloom and shadow? Maybe both.

Even by his own account, I think we can still read into it that Rigaud may have poisoned Monsieur Barronneau, by his slip of the tongue whilst boasting. And as for his wife throwing herself off the cliff … How very convenient that they were walking “like lovers” (after all their arguments) in such treacherous terrain.

So we now have a good idea of Rigaud—and his moustache even makes him look like a pantomime villain :) I chose this illustration our of about a dozen I found, because this is exactly how I see him. One memorable point about him is that whenever he laughs, his moustache goes upwards and his nose moves down, which gives him a very cruel look. It also means that Dickens can cleverly give the reader clues as to when this sinister character appears in the novel—unbeknown to the other characters—and without spelling out his name. Dickens is great at giving us these memorable points to enjoy.

Rigaud, the “devilish” character, also is a good counterbalance to the character “Jean Baptiste”: John the Baptist. He loves these contrasting pairings—perhaps it is to make it more memorable, since people needed to keep these characters in their minds for a lot longer than we do!

Even the tiny tot recognises evil when she sees it: she’s not not afraid of the “caged bird” with a knife, but she is very wary of the one without one. And yet the 1987 adaptation of Little Dorrit I watched, missed out Rigaud completely—such a shame! The most recent one reinstated him, brilliantly played by Andy Serkis (Gollum).

Charles Dickens seems to make a point of starting most of his novels with an unpleasant description—whether a “London particular”, a grimy city rooftop landscape or—as now—an unpleasant description of summer in the South of France, when the sun glares like a lidless, inhuman eye. Dickens is enjoying revelling in his prose again :)

“with people lounging and lying wherever shade was, with but little hum of tongues or barking of dogs, with occasional jangling of discordant church bells and rattling of vicious drums, Marseilles, a fact to be strongly smelt and tasted, lay broiling in the sun one day.”

And now we have a complete contrast! We feel the gloom and claustrophobia of what follows all the more for it. There is a little cell, inside “a villainous prison” which contains two prisoners. Cleverly, Dickens does not name these two until later.

I have the feeling that with this introductory chapter Dickens is setting the stage. And what a lot of foreshadowing there is to be sure!

The title “Sun and Shadow” is very clever. I love the description of the baking hot Marseilles, and the cold, dark, damp prison setting inside, which seems so much more gloomy after having been in the glaringly hot sun.

Also, I believe the description of Rigaud suggests that the shadow is not just literal. He seems such a villain. So I’m wondering which of these is going to be a metaphor for the novel: optimism and sunlight? Or gloom and shadow? Maybe both.

Even by his own account, I think we can still read into it that Rigaud may have poisoned Monsieur Barronneau, by his slip of the tongue whilst boasting. And as for his wife throwing herself off the cliff … How very convenient that they were walking “like lovers” (after all their arguments) in such treacherous terrain.

So we now have a good idea of Rigaud—and his moustache even makes him look like a pantomime villain :) I chose this illustration our of about a dozen I found, because this is exactly how I see him. One memorable point about him is that whenever he laughs, his moustache goes upwards and his nose moves down, which gives him a very cruel look. It also means that Dickens can cleverly give the reader clues as to when this sinister character appears in the novel—unbeknown to the other characters—and without spelling out his name. Dickens is great at giving us these memorable points to enjoy.

Rigaud, the “devilish” character, also is a good counterbalance to the character “Jean Baptiste”: John the Baptist. He loves these contrasting pairings—perhaps it is to make it more memorable, since people needed to keep these characters in their minds for a lot longer than we do!

Even the tiny tot recognises evil when she sees it: she’s not not afraid of the “caged bird” with a knife, but she is very wary of the one without one. And yet the 1987 adaptation of Little Dorrit I watched, missed out Rigaud completely—such a shame! The most recent one reinstated him, brilliantly played by Andy Serkis (Gollum).

message 68:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 02:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

A little more …

I was also struck by how remembering this novel was to be partly about (and any blurb will tell you this, but I’ll put it under a spoiler anyway :)) (view spoiler) I will write more about this place when we come to it in the novel :)

Dickens’s father had been (view spoiler) in 1824, which is around the time this novel begins (since at the beginning, the narrator says it was “thirty years ago”. Dickens himself had been 12 at that time. It evidently made a deep impression on his mind to see his father incarcerated inside such a place. In fact in The Pickwick Papers, when Dickens describes Mr. Pickwick being there, the text takes on a completely different mood.

I was also struck by how remembering this novel was to be partly about (and any blurb will tell you this, but I’ll put it under a spoiler anyway :)) (view spoiler) I will write more about this place when we come to it in the novel :)

Dickens’s father had been (view spoiler) in 1824, which is around the time this novel begins (since at the beginning, the narrator says it was “thirty years ago”. Dickens himself had been 12 at that time. It evidently made a deep impression on his mind to see his father incarcerated inside such a place. In fact in The Pickwick Papers, when Dickens describes Mr. Pickwick being there, the text takes on a completely different mood.

The role of a devil's advocate is one that I never play outside of literature. I really will enjoy reading the bold text that's been posted. Now excuse me while I retire to read Chapter 1...

The role of a devil's advocate is one that I never play outside of literature. I really will enjoy reading the bold text that's been posted. Now excuse me while I retire to read Chapter 1...

Chapter 1 was quite nice. I loved ' the ships blistering in their moorings' most, before we are introduced to the characters. I didn't understand Even the said great personages dying in bed, making exemplary ends and sounding speeches; and polite history, more servile than their instruments, embalming them!

Chapter 1 was quite nice. I loved ' the ships blistering in their moorings' most, before we are introduced to the characters. I didn't understand Even the said great personages dying in bed, making exemplary ends and sounding speeches; and polite history, more servile than their instruments, embalming them!i give this chapter 8/10

Ashley wrote: "It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that it’s slow and ..."

Ashley wrote: "It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that it’s slow and ..."You said my sentiments exactly about Dickens’ writing. It is a cozy, at home, by-the-fire feel. I also read War and Peace - and you are right it is not the same kind of writing; but for me- I loved it. It is at the top of my favorites list as is David Copperfield and Don Quixote! My top three favs!

I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. The illustration you chose aligns with my mental image of Rigaud, as well, Jean. I love the more dangerous character is the one who does not carry a weapon you can see, and we all know you can trust animals and children to sense the evil in a person.

I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. The illustration you chose aligns with my mental image of Rigaud, as well, Jean. I love the more dangerous character is the one who does not carry a weapon you can see, and we all know you can trust animals and children to sense the evil in a person.A very satisfactory start to the novel. If you are a serial reader of the time, you have to be piqued to want to know more about these two.

Like a well, like a vault, like a tomb, the prison had no knowledge of the brightness outside...

I just loved that imagery and the way it introduced impending death an evil into the cell with these men.

Just a possibly unimportant note. I believe Jean Baptist is Italian. "I have brought you bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian)... I remembered being struck that both of the prisoners were foreign and not French.

Sara wrote: "I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. ...I believe Jean Baptist is Italian."

Sara wrote: "I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. ...I believe Jean Baptist is Italian."He definitely has an Italian sounding surname, but maybe later in the book he'll prove to be part French.

Martha wrote: "Ashley wrote: "It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that..."

Martha wrote: "Ashley wrote: "It makes me sad some don’t like Dickens. I just settle in and feel at home when I open his books. The writing is so smooth and beautiful that it’s easy to get lost in! But I get that..."Not really the place to harp on, but you must try cozies to read at the fireplace. The clue is in their name. :)

Sara wrote: "I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. The illustration you chose aligns with my mental image of Rigaud, as well, Jean. I love the mo..."

Sara wrote: "I wonder how many later cartoon and melodrama villains were based on descriptions in Dickens' writing. The illustration you chose aligns with my mental image of Rigaud, as well, Jean. I love the mo..."Sara, it's interesting that Jean Baptist strikes you as Italian. The name sounds French to me. More Interesting though, his name immediately brought to my mind John the Baptist from the Bible. I know that names mean a lot for Dickens so I'm curious to see how this plays out, if at all.

Bionic Jean wrote: "This is a long, powerful chapter to begin with, and if we know what is to come, we might think Marseilles is a strange place to start.

Bionic Jean wrote: "This is a long, powerful chapter to begin with, and if we know what is to come, we might think Marseilles is a strange place to start.Charles Dickens seems to make a point of starting most of his..."

Thank you Jean for breaking it all down! I noticed (and wrote down notes as I read) the heat vs. cold - light vs. darkness. It is nice to “hear” from a Dickens expert your interpretations. This was a great chapter to get into the mood of the story for sure. I love the picture you picked - Much better than the one in my book. It fits Dickens’ descriptions perfectly!

I wasn't really guessing at his being Italian, I was going by the quote that says,

I wasn't really guessing at his being Italian, I was going by the quote that says,"I have brought you bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian)

I am reading this as "the little man" being John Baptist, since the two others present are Rigaud (not little) and the jailer (obviously a Frenchman).

Sara wrote: "I wasn't really guessing at his being Italian, I was going by the quote that says,

Sara wrote: "I wasn't really guessing at his being Italian, I was going by the quote that says,"I have brought you bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Ita..."

Sara, when you wrote, " I believe Jean Baptist is Italian," I thought it was up for question. I didn't recall the text.

I loved the language that Dickens used in describing Marseilles burning in the sun. Everything is so hot and vivid--the white of the houses and streets under the staring eye in the sky. Then, the darkness of the prison where there is little light and no view of the sky.

I loved the language that Dickens used in describing Marseilles burning in the sun. Everything is so hot and vivid--the white of the houses and streets under the staring eye in the sky. Then, the darkness of the prison where there is little light and no view of the sky.Since John Baptist knew the Mediterranean ports, I got the impression that he was an Italian man transporting black market goods by boat.

Connie wrote: "I loved the language that Dickens used in describing Marseilles burning in the sun. Everything is so hot and vivid--the white of the houses and streets under the staring eye in the sky. Then, the d..."

Connie wrote: "I loved the language that Dickens used in describing Marseilles burning in the sun. Everything is so hot and vivid--the white of the houses and streets under the staring eye in the sky. Then, the d..."Good call. I read the first chapter with assiduity. When I realized what Dickens was getting at, it was rewarding.

Connie wrote: "Since John Baptist knew the Mediterranean ports, I got the impression that he was an Italian man transporting black market goods by boat..."

Connie wrote: "Since John Baptist knew the Mediterranean ports, I got the impression that he was an Italian man transporting black market goods by boat..."Yes he was a smuggler, I love the way Dickens reveals this to us - first the list of ports along the coastline, and then making it more explicit with Rigaud’s words “Here I am! See me! Shaken out of destiny’s dice-box into the company of a mere smuggler....”

I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is instantly evocative, and he rounds the chapter off by writing how the stare ‘stared itself out’. It’s much more interesting than just saying ‘night fell’.

I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is instantly evocative, and he rounds the chapter off by writing how the stare ‘stared itself out’. It’s much more interesting than just saying ‘night fell’. The scene with the prisoners was memorable too, as Jean says Rigaud is a kind of melodramatic villain with his moustache and his swirling cloak. Yet he is sinister too, both the child and John Baptist are wary of him, and his crimes are pretty dark.

Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is insta..."

Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is insta..."Brilliant analysis! Looking forward to chapter 2 as well.

Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is insta..."

Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, but it is insta..."Dickens is so good at beating an atmosphere into you. You could not miss the glaring heat or the dark, dingy cell. He does the same thing with his characters...you will not mistake Rigaud for anything but a sinister soul.

Sara wrote: "Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, ..."

Sara wrote: "Pamela wrote: "I love the way Dickens plunges the reader into the story, planting us in Marseilles and the describing the blinding light of the hot day. ‘Staring’ is such an unusual way to put it, ..."Rigaud rhymes with 'nigaud'. I think he might prove to be a bit idiotic despite his sinister introduction.

There you go, your knowledge of French just added to my understanding of the novel. Everything in Dickens is so important and nuanced.

There you go, your knowledge of French just added to my understanding of the novel. Everything in Dickens is so important and nuanced.

Such a dark and contrasting start to this novel. Also, a very unexpected start. I was surprised at finding myself in Marseilles and not in England. LOL!

Such a dark and contrasting start to this novel. Also, a very unexpected start. I was surprised at finding myself in Marseilles and not in England. LOL!I like how Dickens cleverly showed the darkness of the prison. The bright, blistering sun never reaches it or it's inhabitants. They are outside of the warm, sunny World and in a dark world of their own making (or entrapment? or misunderstanding? or circumstances?). Whatever their stories, John Baptiste and Rigaud are not part of the sunny world.

John Baptiste strikes me as a "go with the flow", mild-mannered type. He takes everything in stride. He eats his coarse bread, smokes when cigarettes come his way, gets along with all types....and doesn't regret or covet if these things don't come his way. I suppose a smuggle needs a disposition like this. They have to be able to blend in and "go with the flow".

Good start to the story. Very dark.

Anne wrote: "I know that names mean a lot for Dickens so I'm curious to see how this plays out, if at all."

Anne wrote: "I know that names mean a lot for Dickens so I'm curious to see how this plays out, if at all."Maybe I can say something about John Baptist. Dickens had spent several months in Genoa when he came to Italy. He might have chosen that name because, as he writes in Pictures from Italy, John Baptist was a frequent name in Genoa.

Dickens writes that Saint John the Baptist’s bones were brought to Genoa, and “In consequence of this connection of Saint John with the city, great numbers of the common people are christened Giovanni Baptista.” As a matter of fact, Saint John the Baptist is the Patron Saint of Genoa. Nowadays the name might not be so frequent anymore, though. In my whole life I’ve met only one Giovanni Battista.

I had forgotten this dramatic start to the novel. The hot white city would be something unknown to most English readers, used to cooler, rainier weather.

I had forgotten this dramatic start to the novel. The hot white city would be something unknown to most English readers, used to cooler, rainier weather.Dickens usually gives his characters faces and bodies that match their inner selves. If we had any doubt from the description, Rigaud’s speech gives away his nature.

Sara wrote: "There you go, your knowledge of French just added to my understanding of the novel. Everything in Dickens is so important and nuanced."

Sara wrote: "There you go, your knowledge of French just added to my understanding of the novel. Everything in Dickens is so important and nuanced.":)

My notes start with the first page of Chapter 1. This hit me as very symbolic:

My notes start with the first page of Chapter 1. This hit me as very symbolic:“There was no wind to make a ripple on the foul water within the harbor, or on the beautiful sea without. The line of demarcation between the two colors, black and blue, showed the point which the pure sea would not pass; but it lay as quiet as the abominable pool, with which it never mixed.”

Black vs. Blue

Harbor vs. Sea

Abominable vs. Pure

Foul Water vs. Beautiful Sea

Milena wrote: "Anne wrote: "I know that names mean a lot for Dickens so I'm curious to see how this plays out, if at all."

Milena wrote: "Anne wrote: "I know that names mean a lot for Dickens so I'm curious to see how this plays out, if at all."Maybe I can say something about John Baptist. Dickens had spent several months in Genoa ..."

Thank you, Milena. That's very interesting.

Martha wrote: "My notes start with the first page of Chapter 1. This hit me as very symbolic:

Martha wrote: "My notes start with the first page of Chapter 1. This hit me as very symbolic:“There was no wind to make a ripple on the foul water within the harbor, or on the beautiful sea without. The line of..."

What Dickens wanted to say v/s not? Your interpretation is grounded in metaphors, but IMHO it's a bit of out there.

Martha wrote: "Black vs. Blue

Martha wrote: "Black vs. BlueHarbor vs. Sea

Abominable vs. Pure

Foul Water vs. Beautiful Sea."

I like the contrasts you highlighted Martha. I would add to your list:

- Prisoners who have worn their noble hearts [in the shadow] vs. great kings, and governors, who had made them captive, careering in the sunlight jauntily.

- polite history vs. dark reality

In a word: hypocrisy

- Prisoners who have worn their noble hearts [in the shadow] vs. great kings, and governors, who had made them captive, careering in the sunlight jauntily.

- Prisoners who have worn their noble hearts [in the shadow] vs. great kings, and governors, who had made them captive, careering in the sunlight jauntily.Nice catch, Milena. Hypocrisy. Unfortunately so relevant today.

Listening to my audiobook it is easy to miss so much.

message 96:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 11:12AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I love all these comments - so many thoughts and insights already and we have at least 37 readers on the first day :)

So just to pick up a few threads. I quoted the part about Rigaud's nationality in the summary, and unless we think he's dissembling here for some reason, it will be the truth. My interpretation is that at this point he is a reliable narrator, and that he's boasting to Cavalletto, for all of this chapter. He discloses far more than is "safe" about the criminal activities leading up to his imprisonment, for instance. Here it is again:

“I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss—Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world.”

So just to pick up a few threads. I quoted the part about Rigaud's nationality in the summary, and unless we think he's dissembling here for some reason, it will be the truth. My interpretation is that at this point he is a reliable narrator, and that he's boasting to Cavalletto, for all of this chapter. He discloses far more than is "safe" about the criminal activities leading up to his imprisonment, for instance. Here it is again:

“I am a cosmopolitan gentleman. I own no particular country. My father was Swiss—Canton de Vaud. My mother was French by blood, English by birth. I myself was born in Belgium. I am a citizen of the world.”

message 97:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 11:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I love the contrasts too, plus the extra quotations you picked up Luffy and Sara, and the derivations of the name "Jean-Baptiste", Mila. I hadn't got any further than John the Baptist, to contrast with the devilish Rigaud.

And I agree with Connie, Pamela and Petra, it's a great description of Marseilles, which sounds intolerable to English readers, as Robin picked up. Has anyone been there? Is the heat this intense? And followed in contrast by the stultifying little cell.

And I agree with Connie, Pamela and Petra, it's a great description of Marseilles, which sounds intolerable to English readers, as Robin picked up. Has anyone been there? Is the heat this intense? And followed in contrast by the stultifying little cell.

message 98:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 15, 2020 11:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Thank you for your kind cmment, Martha :) I really enjoyed that quotation and think you are spot on! Mila too.

For these (or any) two prisoners, the sea would represent an impossible, much longed-for freedom. And as you probably know, in Charles Dickens, any mention of flowing water - especially the sea or rivers - is always significant and a strong metaphor. "Abominable pool" - love it! It encompasses the prison, and so much more :)

For these (or any) two prisoners, the sea would represent an impossible, much longed-for freedom. And as you probably know, in Charles Dickens, any mention of flowing water - especially the sea or rivers - is always significant and a strong metaphor. "Abominable pool" - love it! It encompasses the prison, and so much more :)

Sara - re. your comment 77, if you extend the quotation a bit, you can see the context:

"He looked sharply at the birds himself, as he held the child up at the grate, especially at the little bird, whose activity he seemed to mistrust. ‘I have brought your bread, Signor John Baptist,’ said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian); ‘and if I might recommend you not to game—’"

Couldn't the "little man" refer to the prison keeper? It seems more likely to me, given the syntax of the sentence, and since he is the one speaking.

"He looked sharply at the birds himself, as he held the child up at the grate, especially at the little bird, whose activity he seemed to mistrust. ‘I have brought your bread, Signor John Baptist,’ said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian); ‘and if I might recommend you not to game—’"

Couldn't the "little man" refer to the prison keeper? It seems more likely to me, given the syntax of the sentence, and since he is the one speaking.

All the whiteness and heat of Marseilles was giving me a headache and it was a bit of a relief to enter the prison. I enjoyed the the two very different characters there. Also loved that the child (unnamed at this point) picked out the evil one.

All the whiteness and heat of Marseilles was giving me a headache and it was a bit of a relief to enter the prison. I enjoyed the the two very different characters there. Also loved that the child (unnamed at this point) picked out the evil one. It was interesting (after reading David Copperfield) (view spoiler)

Sara (message 72). The cartoon character Snidely Whiplash from Dudley Do-right comes to mind but I do not have any idea if he is based on Dicken's writing.

Milena (message 88). Thanks for the information on John the Baptist. I wondered about the name.

Jean, I love the summaries.

Books mentioned in this topic

My Father As I Recall Him (other topics)Bleak House (other topics)

The Battle of Life (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

Dombey and Son (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...