Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

About a quarter of the way through I thought Dickens had settled on Fagin as an out-an-out devil. There are many satanic allusions, but in this passage he seems barely human.

About a quarter of the way through I thought Dickens had settled on Fagin as an out-an-out devil. There are many satanic allusions, but in this passage he seems barely human. "As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved: crawling forth by night, in search of some rich offal for a meal."

Yes, it's overcoloured and melodramatic. The hyperbole gets a bit much sometimes, and the sentimental speeches such as this one from Dick,""I heard them tell the doctor I was dying, "replied the child with a faint smile. "I am very glad to see you, dear; but don't stop!...I know the doctor must be right, Oliver, because I dream so much of Heaven, and Angels and kind faces that I never see when I am awake. "Kiss me!...Goodb'ye dear! God bless you"

Now even allowing for the time when it was written, this is not how a child would speak! No, it is entirely written for effect, to pull at our heart-strings, and very much the sort of thing Dickens would imagine performed on stage.

It has the faults of a young man's novel. He has not yet learnt how to tailor his passions to the purpose, and his characters are so often mouthpieces. Oliver himself, for instance doesn't always seem like a real person in his own right. He's so reactive and seems more of a character around which to rouse public anger against the treatment of poor children - a sort of Everyman.

But if you view it as Dickens's first proper novel, I think it's an amazing accomplishment! Those characters are still in our culture today. And he only got better!

(view spoiler) is a character who iss neither all good nor all bad, and continually troubled by her conflicting loyalties.

I tend to rate Dickens so highly, that when I come to read a piece by him I try to be as critical as possible. That's why I criticised the character of Oliver, as I don't feel he is entirely consistent.

I tend to rate Dickens so highly, that when I come to read a piece by him I try to be as critical as possible. That's why I criticised the character of Oliver, as I don't feel he is entirely consistent. I do actually think he got a lot better at it, so that the characters are much more consistent from the start, and not just vessels to demonstrate social injustice. I'm afraid I do think that Dickens would have liked to rewrite some of those early passages. Remember he was writing monthly parts of The Pickwick Papers , he'd had a lot of upheaval in his personal life , yet we still expect him to produce perfection straight off with no chance to edit? In his first novel? At 25? Yes he was a genius but not superhuman!

Fagin changes too, in my opinion, but he develops more - at first he's merely crafty and seems quite kind. Mind you, Dickens almost certainly had that idea all along and was duping the readers.

The hothead Grimwig I think is put in partly for light relief, but also as a device for Mr Brownlow to respond to. And to allow the story to increase in tension

"although Mr Grimwig was not by any means a bad-hearted man, and though he would have been unfeignedly sorry to see his respected friend duped and deceived, he really did most earnestly and strongly hope at that moment, that (view spoiler)

So at that point the reader is sitting waiting with the two of them as the hours pass.

The best characters are the minor ones, I think. And there are some wonderful cameos, as we might expect from the author who wrote Pickwick.

Don't you just love the dog, Bullseye?

"Mr Sikes's dog, having faults of temper in common with his owner, and labouring, perhaps at this moment, under a powerful sense of injury...fixed his teeth in one of the halfboots."

and after the part about the devil with his greatcoat on,

"Apparently the dog had been somewhat deceived by Mr Fagin's outer garment; for as the Jew unbuttoned it, and threw it over the back of a chair, he retired to the corner from which he had risen: wagging his tail as he went, to show that he was as well satisfied as it was in his nature to be."

There's a lot of real life in that dog!

Today I started to watch the TV mini-series from 1999 which I mentioned. Half an hour's drama so far and we have not yet reached the start of the novel! It's very good though :)

Today I started to watch the TV mini-series from 1999 which I mentioned. Half an hour's drama so far and we have not yet reached the start of the novel! It's very good though :)

The original illustrations for Oliver Twist are by George Cruikshank, and are very different from those in The Pickwick Papers , but after Oliver Twist , Cruikshank never illustrated another Dickens work. They both remained friends through the 1840s until Cruikshank, who had been a heavy drinker, swung completely the other way. Dickens preferred a more moderate attitude, taking exception to what he saw as Cruikshank's fanatical ravings on temperance and the friendship collapsed.

The original illustrations for Oliver Twist are by George Cruikshank, and are very different from those in The Pickwick Papers , but after Oliver Twist , Cruikshank never illustrated another Dickens work. They both remained friends through the 1840s until Cruikshank, who had been a heavy drinker, swung completely the other way. Dickens preferred a more moderate attitude, taking exception to what he saw as Cruikshank's fanatical ravings on temperance and the friendship collapsed.In 1872, two years after Dickens's death, Cruikshank claimed that the plot and many of the characters from Oliver Twist had been his idea, a claim which Dickens's friend and biographer, John Forster, vehemently denied. And how strange to think that this claim had been made before, all those years earlier, by Seymour's widow about his illustrations for Pickwick.

The Poor Law

The Poor LawOliver Twist was originally published in monthly parts between Feb 1837 - Apr 1839, and this follows hot on the heels of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. It seemed a good idea to read a bit about this.

Previously it had been the duty of the parishes to care for the poor through alms and taxes. They could either go to the parish workhouse or apply for "outdoor relief", which enabled them to live at home and work at outside jobs. But the new Poor Law of 1834 grouped parishes together into unions. Each union had a workhouse, and the only help available to poor people from then on was to become inmates in the workhouse.

As Dickens tells us with bitter sarcasm in chapter 2, the workhouse was little more than a prison for the poor. Civil liberties were denied, families were separated, and human dignity was destroyed. The inadequate diet instituted in the workhouse prompted his ironic comment that,

"all poor people should have the alternative... of being starved by a gradual process in the house, or by a quick one out of it."

The Workhouse

The WorkhouseIt has been suggested that Dickens might have exaggerated the conditions in the workhouses as part of his "persuasive literature" for effect.

I've been trying to find out if that's at all likely, and also if there's any actual workhouse which inspired the one in Oliver Twist. This book by Ruth Richardson, Dickens and the Workhouse: Oliver Twist and the London Poor might be worth a read. She wrote it after discovering that as a boy Dickens had lived within a mile of the "Cleveland Street Workhouse", which was very nearly demolished last year!

Part of the workhouse building continues to be maintained by the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and part of the site is also now occupied by Kier, the construction company responsible for demolishing the adjacent building. Some damage or loss of historical information may already have occurred while this was being sorted out, but it looks as if preservation of the original building is now settled.

Dickens lived in Cleveland Street from when he was nearly 3 to nearly 5 years old. But as we all know, Dickens's father was then arrested for debt and the family was forced to live inside the Marshalsea Debtors' Prison in Southwark.

The family returned to the same house in Norfolk/Cleveland Street several years later, when Dickens was nearly seventeen, and stayed until he was almost twenty. During that time, he was out at work as a young legal clerk, and training himself to become a shorthand court reporter.

Although it may have provided the idea, the Cleveland Street Workhouse was not the only model for the one in Oliver Twist though. Apparently he also based it on the Kettering Workhouse, in Northamptonshire, which he said had been his inspiration. The Kettering Workhouse's bad reputation for ill-treatment was apparently widely known.

Pictures of both the Cleveland Street workhouse, Dickens's childhood home, and some interesting articles (including a feature about a Dickens enthusiast from Toronto, Dan Calinescu stepping in to finance a blue plaque for the house) can be read by clicking here

Antisemitism and Fagin

Antisemitism and FaginThe character of Fagin is introduced in the first chapters. One of the main criticisms of Oliver Twist has always been the antisemitism shown in the author's portrayal of Fagin as a "dirty Jew".

Sadly, it is in keeping with the time. Shakespeare had famously done this much earlier with Shylock in The Merchant of Venice in 1596, setting the play in 16th Century Venice, and it's disheartening to realise that even over 200 years later, that particular prejudice was still rife and actually ingrained into English society. With all great authors we hope that they will somehow manage to step outside the mores of their time, but maybe we expect too much.

Up to a point, Dickens did manage to do that - but only later. Apparently he expressed surprise, when the Jewish community complained about the stereotypical depiction of Fagin at the time Oliver Twist was written (1837). Dickens had befriended James Davis, a Jewish man, and when he eventually came to sell his London residence, he sold the lease of Tavistock House to the Davis family, as an attempt to make restitution. "Letters of Charles Dickens 1833-1870" include this sentence in the narrative to 1860.

"This winter was the last spent at Tavistock House...He made arrangements for the sale of Tavistock House to Mr Davis, a Jewish gentleman, and he gave up possession of it in September."

There is other additional evidence of a rethink, and we have to remember that Dickens was a very young man - still only 25 - when he wrote "Oliver Twist". When editing Oliver Twist for the "Charles Dickens edition" of his works, he eliminated most references to Fagin as "the Jew."

And in his last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend , (1864) Dickens created Riah, a positive Jewish character.

The character of Fagin was modelled on an actual person, a notorious Jewish fence by the name of Ikey Solomon. Dickens also sited him in a real location. Fagin's headquarters in Field-lane had been the location of the hide-out of the notorious eighteenth-century thief Jonathan Wild. Its shops were well known for selling silk handkerchiefs bought from pickpockets. Dickens' letters allude to some of his work being pilfered,

"when my handkerchief is gone, that I may see it flaunting with renovated beauty in Field-lane."

When referring to Fagin Dickens often uses symbols that are normally reserved for the Devil. When we first meet him, we find him roasting some sausages on an open fire, "with a toasting fork in his hand", which seems to be so important to Dickens that it is mentioned two more times in the course of the text. In the next chapter we find Fagin equipped with a fire-shovel. Also the term the merry old gentleman seems to be a euphemistic term for the Devil - in line with Old Harry, Old Nick, Old Scratch etc.

Fagin as a personnification of Evil

Fagin as a personnification of Evil Here are two quotations about Fagin - one to show his intentions and one as a rather highly-coloured (let's fact it, the whole novel is highly coloured and populist!) description of him.

"In short, the wily old Jew had the boy in his toils. Having prepared his mind, by solitude and gloom, to prefer any society to the companionship of his own sad thoughts in such a dreary place, he was now slowly instilling into his soul the poison which he hoped would blacken it, and change its hue forever."

"It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved: crawling forth, by night, in search of some rich offal for a meal."

Dickens also provides us with a further interpretation, which I mentioned before. Victorian society placed a lot of value and emphasis on industry, capitalism and individualism. And who embodies this most successfully? Fagin - who operates in the illicit businesses of theft and prostitution! His "philosphy" is that the group’s interests are best maintained if every individual looks out for himself, saying,

"a regard for number one holds us all together, and must do so, unless we would all go to pieces in company."

This is indeed heavy irony on Dickens's part, and adds to Fagan's multi-layered personality. As I remember, there are clues in the novel that he has his origins in circus folk from Eastern Europe. Apart from the long cloak and flamboyant charades though, I haven't picked up any info as to that yet.

Sometimes Dickens seems to be saying that a good person will behave nobly and decently in whatever situation and circumstances. There are countless examples of "the noble poor". Nancy, however seems to indicate Dickens making a case for the opposite idea, that good people can be warped by bad experiences and fall into vice.

This is good psychology. It would be so easy for an author to take a stereotypical view of children having early influences which then inform their later behaviour and ethics to such a ridiculous extent that they all behave the same way. Dickens can be guilty of "persuasive literary techniques" yes; he likes to tell us what to think. But he is too great an author to put his characters into straitjackets for this purpose. Diversity of characterisation is one of his great strengths. He first showed this with his plethora of characters in The Pickwick Papers.

Is Fagin a comedic over the top character? It fits Charley Bates, Mr Bumble, and a whole lot of other characters. In a way every character is a gross exaggeration of a general type, stock figures, and sometimes over-simplistic - either all good or all bad.

Is Fagin a comedic over the top character? It fits Charley Bates, Mr Bumble, and a whole lot of other characters. In a way every character is a gross exaggeration of a general type, stock figures, and sometimes over-simplistic - either all good or all bad.The more I look into Dickens's life, the more evidence I find for a true basis of his fictitious characters. You can see that the real-life counterparts actually performed similar atrocious acts to those of their fictional counterparts. As well as Ikey Solomon and Jonathan Wild (my comment 236) there's also the ruthless magistrate, Mr. Fang. It turns out that he is entirely based on a real person who could well have been even more severe in reality than Dickens's Mr Fang (although don't you just love that name? LOL) In a letter dated June 3, 1837, Dickens wrote to his friend Thomas Haines,

"In my next number of Oliver Twist, I must have a magistrate...whose harshness and insolence would render him a fit subject to be "shewn up"...I have...stumbled upon Mr. Laing of Hatton Garden celebrity."

Allan Stewart Laing served as a police magistrate from 1820-1838, before being dismissed by the Home Secretary for what sounds like abuse of his power. Dickens even went so far as to ask Haines, an influential police reporter to smuggle him into the Hatton Garden office so he could get an accurate physical description of him! Dickens used to be a reporter before giving it up to write Oliver Twist as well as finishing off The Pickwick Papers , so perhaps he had the connections to make it quite an easy task for him.

So I'm wondering if many more of these comic or drastically exaggerated characters, such as Mr Bumble, Mrs Corney, Mrs. Sowerberry, etc. have their counterparts in reality and may not be exaggerations after all. Dickens had previously studied and sketched the office of beadle in "Sketches by Boz", so the character of Mr Bumble with his hypocritical, harsh behaviour could well have started with that.

I think we remember some of these characters for a long time after we have read the book. They are so vivid and powerful that they seem to adopted a life of their own, beyond the confines of the stories. And so, Fagin, Mr. Pickwick, Little Nell, Mr. Micawber and many others have actually become some sort of myth. They appeal to us and stimulate our imaginations. But also it might explain why when some people come to read Dickens they find him over-long.

Miss Havisham too - she is such an amazingly vivid character - far more so than "Little Nell"!

It's still less than 2 weeks since I started Oliver Twist, and I don't think I'd want to read it any faster to be honest. I've just read the most dramatic bit in the whole story now - wow!! I'm not surprised the females fainted in the aisles when Dickens did his readings of that!!

Some more thoughts about the events very near the end of the book, so I'll use spoilers.

Some more thoughts about the events very near the end of the book, so I'll use spoilers. Fagin's guilt

(view spoiler)

Bullseye

At the beginning we were told that Bullseye had "faults of temper in common with his owner". By this amusing quip Dickens makes the dog a symbolic emblem of his owner's character. He is vicious, just as Sikes has an animal-like brutality.

(view spoiler)

Readership

"Masses of the illiterate poor chipped in ha'pennies to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers."

from Hauser, Arnold [1951]. The Social History of Art: Naturalism, Impressionism, the film age. The Social History of Art 4. (1999)

I've found a "historically accurate" novel by him, The Final Recollections of Charles Dickens: A Novel sounds a good read!

Dickens's own readings/performances must partly have been so popular because they could appeal even to those who were illiterate. Simon Callow has done brilliant reconstructions of these.

Thoughts on Nancy and Bullseye ... (view spoiler)

Prostitutes

I suppose I have assumed prostitutes were illiterate at that time. I doubt very much whether they would have had the ready cash - or the inclination - to buy "Bentley's Miscellany" would they? There was a public outcry against the subject material, yes. It was thought to be highly immoral.

Edit: from David Perdue,

Dickens was severely criticized for introducing criminals and prostitutes in Oliver Twist, to which Dickens replied, in the preface to the Library Edition of Oliver Twist in 1858,

"I saw no reason, when I wrote this book, why the very dregs of life, so long as their speech did not offend the ear, should not serve the purpose of a moral, at least as well as its froth and cream."

Go Dickens! The inimitable and the innovator!

Go Dickens! The inimitable and the innovator!Blathers and Duff

Yet another example of Dickens's light relief is in his inclusion of these two detectives. I had previously thought that Inspector Bucket in Bleak House in 1852 was the earliest example Dickens wrote of a police detective.

But this creation of the duo dates, from 1837! And that means it is even earlier than The Murders in the Rue Morgue which was written by Edgar Allan Poe in 1841! That is usually credited as the first example of a fictional detective, and in England The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins which was later in 1868. The first mention of Sherlock Holmes by Conan Doyle, Sir Arthur which is often cited was actually considerably later in 1887.

I'm sticking to Dickens unless anyone ever finds an earlier example :)

I finished reading Oliver Twist yesterday (Mar 15 2014). Today I'm writing my review, which will hopefully be ready to post soon :)

I have now finished and posted my analytical review of the book here . I hope anyone else who's been reading it will also enjoy my review :)

I have now finished and posted my analytical review of the book here . I hope anyone else who's been reading it will also enjoy my review :) The idea that Dickens's routine was to write his difficult "Oliver Twist" passages first, comes from a biography of him Charles Dickens by Jane Smiley. Generally I like Peter Ackroyd on Dickens, but she also has some interesting facts.

The idea about the consequent lightening of mood in Oliver Twist after the serialisation of The Pickwick Papers had finished was my own theoretical deduction, though.

I personally think Dickens's historical novels are his weakest.

And I'll happily chat about Oliver Twist with anyone, any time :)

According to the original publication dates (comment 25) September 1838's issue seems to be missing! This intrigued me, as I know he never missed any literary deadlines, except for when Mary Hogarth died.

According to the original publication dates (comment 25) September 1838's issue seems to be missing! This intrigued me, as I know he never missed any literary deadlines, except for when Mary Hogarth died.His journal for 1838 says that in September he asked Richard Bentley (the owner of the magazine "Bentley's Miscellany", of which Dickens was the editor, and in which Oliver Twist was serialised as above) if he might miss a month's installment of Oliver Twist. He then went to the Isle of Wight for about nine days.

On the 22nd Dickens signed an agreement with Bentley concerning the Miscellany and the publication of Barnaby Rudge.

The two didn't seem to get on, however. They fell out over editorial control, and Dickens called Bentley a "Burlington Street Brigand". He quit as editor in 1839.

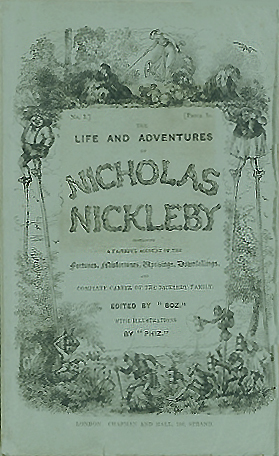

Sometimes I get confused, and think what it must be like for Dickens! He was writing two separate serialised novels, researching another, agreeing a contract for a fourth, and editing two magazines, all at the same time! For Nicholas Nickleby he visited Yorkshire, in January 1838 with Hablot Browne to look at Poor schools as research.

Sometimes I get confused, and think what it must be like for Dickens! He was writing two separate serialised novels, researching another, agreeing a contract for a fourth, and editing two magazines, all at the same time! For Nicholas Nickleby he visited Yorkshire, in January 1838 with Hablot Browne to look at Poor schools as research.I like this:

Just a few thoughts, moving from Oliver Twist to Nicholas Nickleby.

Just a few thoughts, moving from Oliver Twist to Nicholas Nickleby.Moving on from Oliver Twist:

Dickens had been criticised for writing his novel about thieves, prostitutes and murderers; one critic writing,

"It is a hazardous experiment to exhibit to the young these enormities".

We know that he wanted to broaden the scope of fiction, without displaying the false attitudes which had gone before. The critic Humphry House said that this novel, "permanently affected the range, status and potentialities of fiction." When talking of Dickens's use of thieves and prostitutes as his characters, he commented, "In his knowledge of such things, Dickens was by no means unique; but using it in a novel, with all the heightened interest of a vivid story, he brought it home to the drawing rooms... where ignorance... might be touched. In The Newcomes, William Makepeace Thackeray made Lady Walham take "Oliver Twist" secretively to her bedroom."

Oliver Twist was a very topical novel, and Dickens was keen to describe the atrocities resulting from the amendment of the Poor Law, (as I've remarked before.) In the third year of the new law there was a severe winter, in the fourth a depression, which resulted in food becoming both scarce and highly priced in the fifth. The Poor Law became more and more unpopular, as Dickens's novel increased in popularity and began to seem almost prophetic.

Dickens's volatile passion, indignation and sarcasm in this novel - particularly in the first chapters - is due both to his youth and inexperience as a writer of novels. As we saw, this is a young man's novel, about the iniquitous social conditions of the time, but using the popular literary conventions, and liking for melodrama.

Coincidences abound, but Oliver collapsing on the steps of the house where Rose Maylie (view spoiler) lives, is after all mirrored 10 years later by Charlotte Bronte, when Jane Eyre collapses on the doorstep of her unknown cousins! In our modern cynicism, we criticise such obvious convenient plot devices, but the Victorian loved them! It was very much part of their idiom of story-telling.

Yet in my opinion he improved as a writer. Humphry House, again,

"It was Dickens's first attempt at a novel proper. The sequence of the external events which befall Oliver and form the framework of the book, though improbable, is at least straightforward, organised, and fairly well proportioned; but all the subordinate matter designed to explain and account for these events is at once complicated and careless... Many conundrums are solved "off", and are then expounded to the audience in hurried, uneasy dialogue."

I suppose he does have a point. I often wonder if Dickens were still alive, would he want to rewrite some of his earlier works? But then I think, no, of course, he would want to be writing something new!

Moving towards Nicholas Nickleby:

Moving towards Nicholas Nickleby:So what are we to expect from the next? We know that prior to Nicholas Nickleby Dickens had seen advertisements in the London papers for cheap boarding schools in Yorkshire. It was stressed that there were "no holidays" from these schools. They were a convenient place to dispose of unwanted or illegitimate children. We saw that during the writing of Oliver Twist Dickens and his friend, Hablot Browne (who was to illustrate the book) travelled in secret to Yorkshire to investigate these schools in January 1838. There they met William Shaw, the headmaster of Bowes Academy. The neglect and maltreatment at this notorious school was responsible for several boys' blindness, and some died as a consequence.

I have no doubt that we will encounter Dickens's take on William Shaw, just as in Oliver Twist he based several of his characters on real people, such as Ikey Solomon (Fagin). But I'm not going to "spoil" anything! I also suspect that Dickens will find it difficult to keep his indignation and social conscience about these dreadful institutions in check.

He was writing at breakneck speed again. Oliver Twist had overlapped The Pickwick Papers by 10 months, and when he started Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist was still a long way from being completed. So the writing in the early part of this novel is perhaps going to feel very familiar, having been written on the same days as the latter half of Oliver Twist. He was also, of course, doing his editing work too. When under pressure, he seemed to just take on more projects and speed them all up!

Here's the schedule for publication of Nicholas Nickleby. He was 26 to 27 during the writing of this novel. In June 1839 Dickens sat for the "Nickleby Portrait"; an engraving of this is used as the frontispiece. It is by the artist Daniel Maclise, and was commissioned by Dickens's publishers, Chapman and Hall. The last part, again, is a double issue.

Here's the schedule for publication of Nicholas Nickleby. He was 26 to 27 during the writing of this novel. In June 1839 Dickens sat for the "Nickleby Portrait"; an engraving of this is used as the frontispiece. It is by the artist Daniel Maclise, and was commissioned by Dickens's publishers, Chapman and Hall. The last part, again, is a double issue.I – March 1838 (chapters 1–4);

II – April 1838 (chapters 5–7);

III – May 1838 (chapters 8–10);

IV – June 1838 (chapters 11–14);

V – July 1838 (chapters 15–17);

VI – August 1838 (chapters 18–20);

VII – September 1838 (chapters 21–23);

VIII – October 1838 (chapters 24–26);

IX – November 1838 (chapters 27–29);

X – December 1838 (chapters 30–33);

XI – January 1839 (chapters 34–36);

XII – February 1839 (chapters 37–39);

XIII – March 1839 (chapters 40–42);

XIV – April 1839 (chapters 43–45);

XV – May 1839 (chapters 46–48);

XVI – June 1839 (chapters 49–51);

XVII – July 1839 (chapters 52–54);

XVIII – August 1839 (chapters 55–58);

XIX–XX – September 1839 (chapters 59–65).

There's a film from 2002-3 directed by Douglas McGrath, with Jamie Bell as Smike, which was a good one.

There's a film from 2002-3 directed by Douglas McGrath, with Jamie Bell as Smike, which was a good one. Here's the cast list for the 1947 film of Nicholas Nickleby. I particularly remember James Hayter playing the Cheeryble brothers. This was the first "sound" version after the two previous silents from, 1912 or - incredibly - 1903! Black and white. I'll paste the cast here:

Sir Cedric Hardwicke ..... Ralph Nickleby

Stanley Holloway ..... Vincent Crummles

Derek Bond ..... Nicholas Nickleby

Mary Merrall ..... Mrs. Nickleby

Sally Ann Howes ..... Kate Nickleby

Aubrey Woods ..... Smike

Jill Balcon ..... Madeline Bray

Bernard Miles ..... Newman Noggs

Alfred Drayton ..... Wackford Squeers

Sybil Thorndyke ..... Mrs. Squeers

Vera Pearce ..... Mrs. Crummles

James Hayter ..... Ned and Charles Cheeryble

Emrys Jones ..... Frank Cheeryble

Cecil Ramage ..... Sir Mulberry Hawk

Timothy Bateson ..... Lord Verisopht

George Relph ..... Mr. Bray

Frederick Burtwell .... Sheriff Murray

But I prefer the version with Charles Dance, as Ralph Nickleby. He is superb. It was very well acted throughout, and for such a long novel, a TV series contains more of the "meat." This was a 3 hour TV adaptation from 2002. I don't think the earlier one from 1977 with Nigel Havers is as good.

What I would really LOVE to see, and don't have a hope of, is the eight and a half hour version! It dates from 1982 and was a joint production between the Royal Shakespeare Company and Channel 4 - being their first broadcast drama over two evenings. Trevor Nunn directed, and there are a few DVDs around, but they are very rare :(

I find with abridged audio books that the story of a long classic novel can be completely different in each version! That's why I don't like them. But with a TV or film, there is the added joy of the sets, period feel, atmosphere etc which can really bring them to life and make up for it a bit.

Started Nicholas Nickleby today :) (12.15)

Started Nicholas Nickleby today :) (12.15)It seemed a bit slow to start I thought, with all the rather heavyhanded humour relating to the "United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company".

But as soon as Ralph Nickleby came on the scene it started to pick up, "there was something in his very wrinkles, and in his cold restless eye, which seemed to tell of cunning that would announce itself in spite of him." What a cold fish! He took against Nicholas right from the start - and the only reason seems to have been that Nicholas was young, bright and open! Miserable old skinflint! :(

I've only read the first 3 chapters and felt there was enough to take in in one sitting there! Usually one issue was 3 chapters. I'll probably read 2 or 3 chapters per day.

I've only read the first 3 chapters and felt there was enough to take in in one sitting there! Usually one issue was 3 chapters. I'll probably read 2 or 3 chapters per day.I have yet to read Claire Tomalin's biography (have read Ackroyd's and another) and also her novel Invisible Woman. I'm afraid it's clear that Dickens tended to say one thing and do another. I think his heart was in the right place; he just couldn't see the inconsistency. But it's a bit hard to understand and reconcile with his pioneering views :( One writer has said he was "among the best of writers and among the worst of men" (an article printed in The Atlantic (theatlantic.com) on 13 April 2010, by Christopher Hitchens).

I also like Miriam Margolyes' show "Dickens' Women" and have a recording, although only audio, sadly. I particularly laugh when she coincidentally finds all the perfect heroines to be just....seventeen! When you read the books, they are indeed! (I think this was the age at which Mary Hogarth, his sister-in-law) died.

I've encountered the wonderful Wackford Squeers though, with his

I've encountered the wonderful Wackford Squeers though, with his "one eye where the popular prejudice is in favour of two"

LOL! (From memory - hope it is correct.)

I've been dipping into a book by a Charles Dickens scholar Humphry House, and this is what he said about "The United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company",

I've been dipping into a book by a Charles Dickens scholar Humphry House, and this is what he said about "The United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company","Companies are shady, promoted by a few unscrupulous people as an extension of already shady traffic. The United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company might well belong to the speculative rage which preceded the great crash of 1825-6, when steam-ovens, steam-laundries, and milk-and-egg companies competed with canals and railways for the public's money. The Muffin Company's benevolent propaganda about benefits to the human race, which made the men cheer, and the women weep, is admirably true to the spirit of those progressive years. But with Ralph Nickleby on the Board, neither its moral nor its financial status was much above..." and then he quotes a fraudulent company from a future novel.

It's interesting to see how Dickens's novels are so very specific and topical. We've already seen an example of that with the Poor Law amendments in Oliver Twist. Now in Nicholas Nickleby, not only do we have the very topical subject of the notorious Yorkshire Poor Schools, but also the financial shenanigans of the time, with con-artists able to make a fortune by hoodwinking the general public.

Chapter 6 - found those stories rather twee. Some of the stories Dickens inserts are brilliant - he often uses ghost stories for example - but not here.

Chapter 6 - found those stories rather twee. Some of the stories Dickens inserts are brilliant - he often uses ghost stories for example - but not here. At first the melancholy traveller is reluctant to tell a story. Then the story he tells, "The Five Sisters of York", is itself a gloomy tale full of sorrow. Afterwards the happier traveller tells a funny story to counter-balance the effect.

It's been suggested that Dickens might be letting us know the tone the whole novel was going to take. "Nicholas Nickleby" is going to have sufferings and dark deeds, as did "Oliver Twist", but its spirit will be more light-hearted, like "The Pickwick Papers". Life for the "Five Sisters of York" was sad, but they did not allow such sorrow to prevent them from retaining a more serene outlook on life. And then "The Baron of Grogzwig" was a light-hearted tale in itself, to follow.

A plausible explanation, perhaps? A way of excusing what were really tiresome stories which merely delayed the action? Ah... but then this is over-analysing, because in fact that's just what they were - a delaying tactic. No hidden meaning or significance. It's so easy to look for deep meaning in things - and to come up with all sort of contorted constructs. But I tend to think that Dickens always said what he meant - or used so much hyperbole that the meaning was crystal clear ...

A little delving reveals that in fact all Dickens was doing was filling out the second installment, for April 1838 (chapters 5–7)! In a letter to Forster probably written on 15 April 1838, the day he was supposed to deliver his copy to his publishers, he wrote,

"I couldn't write a line till three o'clock and have yet 5 slips to finish, and don't know what to put in them for I have reached the point I meant to leave off with". So he did just stick in a couple of stories he had lying around, handy! LOL

We have to consider the colossal amount of work he had taken on, with Oliver Twist overlapping The Pickwick Papers by 10 months, and then when he started Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist was still a long way from being completed. He was also, of course, doing his editing work too. Perhaps we really need to cut him a bit of slack on this :)

I love the bits about the Squeers family, ch 8 and 9 :) I'm up to chapter 13 now.

Mrs Nickleby is just a bit dim, I think. Dickens say that Ralph Nickleby easily makes her view her husband in a negative light, until,

Mrs Nickleby is just a bit dim, I think. Dickens say that Ralph Nickleby easily makes her view her husband in a negative light, until,"she had come to persuade herself that of all her husband's late creditors she was the worst used and the most to be pitied."

I'm beginning to wonder if one of the reasons she's deliberately made to appear slow, is to contrast with the devious manipulations of her brother-in-law, Ralph.

Oh wow - this is about William Shaw and Bowes Academy:

Oh wow - this is about William Shaw and Bowes Academy:http://www.researchers.plus.com/shaw.htm

There's no doubt that Dickens intended the headmaster Wackford Squeers to be a portrayal of William Shaw, and that Dotheboys Hall was Bowes Academy. Incredible testimonies from the two young boys. How Dickens managed to write about this so entertainingly - and influenced social reform by doing so - just amazes me. The man was a genius.

A few more chapters and I am relishing this story now we're really into it. I gave a little cheer when Nicholas (view spoiler) I was reading in my garden in the sunshine, and had already been chortling quite a bit at what had gone before...

A few more chapters and I am relishing this story now we're really into it. I gave a little cheer when Nicholas (view spoiler) I was reading in my garden in the sunshine, and had already been chortling quite a bit at what had gone before...I must admit I had forgotten the tone of this novel. Many of the speeches seem to cry out for an actor's ringing declamation on stage. You can see Dickens's love of the theatre!

But I particularly enjoy the contrasts. The tragic scenes are so much more powerful, because of the contrasting comic scenes. And who, out of the general reading population, would really have stayed with a piece of tragic literature about their contemporaries - including the poorest of them all - had it not been made so hugely entertaining?

It's a real rarity for the time, for an author to focus on the lives of such poor people. Noggs and Smike are fully developed characters, but I cannot see Dickens's contemporary, Thackeray, bothering with them. And it's even less likely that his most popular predecessor, Jane Austen would.

Here's some of the testimony of the children. It sounded as if the conditions were incredibly neglectful, even allowing for the time. This is copied verbatim from William's evidence to the court in 1823. He was 11 years old.

Here's some of the testimony of the children. It sounded as if the conditions were incredibly neglectful, even allowing for the time. This is copied verbatim from William's evidence to the court in 1823. He was 11 years old."When any of them got a hole in the jacket or trousers, they went without till they were mended. The boys washed in a long trough, like what horses drink out of: the biggest boys used to take advantage of the little boys, and get the dry part of the towel. There were two towels a day for the whole school. We had no supper; nothing after tea. We had dry bread, brown, and a drop of water and a drop of milk warmed. The flock of the bed was straw; one sheet and one quilt; four or five boys slept in a bed not very large.

My brother and three more slept in my bed; about thirty beds in the room, and a great tub in the middle, full of ----. There were not five boys in every bed. The tub used to be flowing all over the room. Every other morning we used to flea the beds. The usher used to cut the quills, and give us them to catch the fleas; and if you did not fill the quill, you caught a good beating. The pot-skimmings were called broth, and we used to have it for tea on Sunday; one of the ushers offered a penny a piece for every maggot, and there was a pot-full gathered: he never gave it them. No soap, except on Saturday, and then the wenches used to wash us.

I was there nine months, and there was nothing the matter with me. One morning I could not write my copy, from the weakness of my eyes: I felt nothing the night before. Mr. Shaw said he would beat me if I did not write my copy. Next morning he sent me into the wash-house. There were other boys there; some quite blind. Mr. Shaw would not have us in his room. I was there a month. There were 18 boys at one time affected; some who were totally blind were sent into a room; I think two besides myself. In about a month I was removed to a private room, where there were nine totally blind. A doctor was sent for. Mr. Benning is his name. I was in the room two months; the doctor discharged me, saying, I had lost one eye, and should preserve the other. I had lost one eye, but I could not see with the other. I was taken back to the washhouse, and never had the doctor again; I was taken home in the month of March.

I was only to learn to read and write. there were boys learning Latin, and two or three French. There were seven ushers. One of the name of Evans was there, for the purpose of instruction. When any of the boys had any thing amiss, Evans assisted them. He had bad eyes. His father used to send him down bottles of stuff from London. Evans used to blow dust in the eyes of the boys who were ill. Mr Benning lives in Barnard Castle. He used to look over the boys' eyes, and turn them away again. He never did any thing else. The boys had no physic nor eye-water. He just came to look at them."

That sounds pretty much like Dotheboys Hall to me :(

So far I find them comic characters - grotesques to add light relief to something we would otherwise find too distressing to read.

So far I find them comic characters - grotesques to add light relief to something we would otherwise find too distressing to read.I just love the names! Dotheboys Hall the vile school where the boys were well and truly "done to" - it became so infamous that "Bowes Academy", which we've been talking about was eventually (by 1903) known as "Dotheboys Hall"!

And Wackford Squeers, the headmaster, overkeen on whacking his pupils. Miss Knag - the spiteful forewoman. No need to wonder what her manner was like!

Then just today I read about Lord Frederick Verisoft - soft of brain - "weak and silly", his friend the Honourable Mr Snobb, and Sir Mulberry Hawk - "the most knowing card in the pack" - who treats everyone, including his "friends", as his prey.

So many fantastically memorable names!

I've just discovered another character who was based on a real person. Miss La Creevy was based on Rosa Emma Drummond, who painted a miniature engraved portrait of Dickens on ivory. He had commissioned this so that he could give it to his fiancee, Catherine Hogarth as an engagement present. Like Miss Drummond, Miss La Creevy, was a good-natured, middle-aged miniature painter, described by Dickens as a "mincing young lady of fifty".

I've just discovered another character who was based on a real person. Miss La Creevy was based on Rosa Emma Drummond, who painted a miniature engraved portrait of Dickens on ivory. He had commissioned this so that he could give it to his fiancee, Catherine Hogarth as an engagement present. Like Miss Drummond, Miss La Creevy, was a good-natured, middle-aged miniature painter, described by Dickens as a "mincing young lady of fifty".I'm also enjoying all the minor characters such as Mr Crowl, who "utters a low querulous growl", Mrs Wititterly who seems to witter a lot and has "an air of sweet insipidity" and the best of the lot, Sir Tumley Snuffim, who is perhaps not such a good doctor if his patients "snuff it"!

It's such a shame that I know I'm going to forget this wealth of cameos as soon as I finish the book.

I'm up to chapter 26 now :)

I'm up to chapter 26 now :) Re. the theatre chapters. Even though it's a long novel, a lot of these groups of characters such as the acting troupe, and also the Kenwigses, the beneficent employers, the non-Squeers characters in Yorkshire, etc - aren't very developed, and we want to read more about them. Perhaps it's just the result of the serial method of production, and Dickens' fertile mind - his mind just must have been running on ahead of him all the time I guess. So many characters...

It seems the Infant Phenomenon (or "Infernal Phenomenon" as the leading man Mr Folair termed her LOL!) was also based on a real person! Is there anyone in this novel who wasn't...

"Dickens modelled Vincent Crummles and his daughter Miss Ninetta Crummles on the actor-manager T.D. Davenport and his daughter Jean. "Infant phenomena" were a regular feature of many theatrical shows during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Davenport and his daughter appeared on the Portsmouth stage in March 1837, and playbills announced that the nine-year-old prodigy would play a variety of parts, including Shylock, Little Pickle and Hector Earsplitter, sing songs ranging from "Since Now I'm Doom'd" to "I'm a Brisk and Sprightly Lad Just Come Home from Sea" and dance both sailor's hornpipes and Highland flings."

I'm wondering why she was voiceless- is this just to help or heighten the illusion of her youth? I assume that Dickens must be making a particular point, as she does not say one word in the text, whereas all the rest of the company seem to be chatterboxes. But perhaps after all it's not symbolic, and merely part of her persona.

I have just noticed that the introduction to one of my copies of Nicholas Nickleby is by Dame Sybil Thorndike! Now that I must read :)

Mrs Nickleby - is rather self centred, as well as stupid. She's certainly not very loyal to her own family, despite their devotion to her. She reminds me of Mrs Bennett in "Pride and Prejudice" - silly and confused - a comic character. She changes her opinion all the time, and keeps saying the opposite of what happened. But the fact that she takes no responsibility for the misfortune of her husband, even though she encouraged him to speculate, does make me wonder if it's malicious.

Mrs Nickleby - is rather self centred, as well as stupid. She's certainly not very loyal to her own family, despite their devotion to her. She reminds me of Mrs Bennett in "Pride and Prejudice" - silly and confused - a comic character. She changes her opinion all the time, and keeps saying the opposite of what happened. But the fact that she takes no responsibility for the misfortune of her husband, even though she encouraged him to speculate, does make me wonder if it's malicious.Dickens's own mother, Elizabeth Dickens, was the model for Mrs. Nickleby. Luckily for Charles she didn't recognise herself in the character. In fact she asked someone if they "really believed there ever was such a woman"!

There's a preoccupation - a recurring theme - of the parent-child relationship which is very interesting in this novel. Perhaps Dickens himself was slightly more conscious that he should give time and attention to this (as he never seemed to with his marriage) or maybe it's a consequence of his own troubled youth.

Other books which could relate to this one:

Other books which could relate to this one:Peter Ackroyd's is the definitive biography of Dickens in my view. It was ground-breaking at the time, because until then nobody had written a biography of a person which was also a detailed study of the culture

Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World by Simon Callow

Edit - I read this following on from Nicholas Nickleby, and enjoyed it enormously. Because Simon Callow has a unique perspective (an actor and closet writer, writing about a writer and not-so-closet actor/manager!) he has some great insights. The book goes more into the theatrical world than any other bio of Charles Dickens that I've read, and derives interesting psychological conclusions - such as evidence of multiphrenia, which seems very likely to me. As I said, Dickens would often leap up to check his own expression in the mirror...

Here's my review

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Pictures Printed From the Original Wood Blocks

Claire Tomalin's biography is on my shelf to read. And her novel about Nelly is on my Kindle. I can't quite remember what Peter Ackroyd said, but Tomalin is apparently very damning. We now know of Dickens's disgraceful treatment of his wife, and it appears that Dickens bemoaned the appearance of each child after the first few. I've been told he blamed his wife for them, as if they were nothing to do with him. He seemed to want girls and for them never to grow up into independent women. (You can kind of tell this by his novels.) especially hated the coming of more boys, and tried to dictate the lives of his sons, "denying one his wish to become a soldier, then decrying his lack of success in the career he pushed him into. Others he was glad to get rid of anywhere abroad." Someone else said the generaling feeling you get of Dickens from the Tomalin biography is that he devoted a lot of time to people in poverty and forgot his own family.

I'm wondering if Tomalin might have exaggerated for effect. Maybe for a clear picture one needs to also read the accounts by his children. But clearly he didn't seem to know himself very well (that's the kindest way I can think of putting it!) and seems such a hypocrite sometimes. But it could maybe just be the truth - Tomalin always backs her opinions up by use of written evidence much of which was hidden or ignored until recently. Apparently one of the quotes by Dickens himself, suggests he knew his bad side, and represented it in some of his bad characters. Tomalin is one of our best literary biographers thouigh - they are so well researched but readable. Her book Thomas Hardy was a real eye-opener too!

I suppose I wonder about selectively choosing her evidence, or heightening some of it, because of her also writing a novel Invisible Woman about Nelly. But presumably she is concerned about her academic integrity, so probably has been quite scrupulous.

As well as wondering about Dickens's children's accounts, I'm wondering about reading his letters. I've found parts of those have cast a light on certain events. But perhaps they're not to be trusted where his children are concerned. Perhaps he's an "unreliable narrator" there! LOL

It's interesting to speculate on whether Davenport falsified the age of his daughter, by 6 years, as Crummles does. It must have been a great temptation in that business, I would think. Like child actors playing younger and younger parts as they got older and (the girls) being "strapped into" their costumes.

The Cheeryble brothers were based on real life characters too!

The Cheeryble brothers were based on real life characters too! They are based on two benefactors who were brothers, Daniel and William Grant. They came from Scotland, but settled in Ramsbottom in Greater Manchester (although during Dickens's time, this will have been thought of as part of the county of Lancashire.) Some of the fine houses they built are still there. For instance, St Andrew's Church from 1832 is also known as Grant's Church. It was originally consecrated as a Scottish Presbyterian Chapel, with a donation of £5,000 by William Grant. They regularly gave money to promising new enterprises and for education, supporting schools, libraries and the charitable institutions, and when homes and farmlands on Speyside were swept away by floods in 1829, gave £100 to swell "The Flood Fund".

Dickens was keen to make sure everyone knew of these remarkable pair. This is from his preface,

"It may be right to say that there are 2 characters in this book which are drawn from life. Those who take an interest in this tale will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble do live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, noble nature and unbounded benevolence are no creatures of the author’s brain, but are prompting every day some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour." May, 1848.

I finished reading Nicholas Nickleby a few days ago. Here's my review , which can be quite safely read even if you haven't finished (or even started!) it yet. There are no spoilers.

I finished reading Nicholas Nickleby a few days ago. Here's my review , which can be quite safely read even if you haven't finished (or even started!) it yet. There are no spoilers.Elements of the book are farcical and very "broad". Since he dedicated it to his friend, the distinguished actor and theatre director William Macready, I wonder whether this was deliberately hyped up and exaggerated, or whether the dedication came as a result. Sort of chicken and egg situation.

Dickens is always great for a reread, as I remember some of the main characters so well, but other minor ones come up as "new" every time I read it. A perfect example in this one isthe Cheerbyle brothers. I had remembered the characters very well, but not the book in which they occurred! Weird.

It's nice to wonder how Dickens would reconstruct his novels, if they no longer had to be written in serial form. I suppose with each new "adaptation" for cinema or TV, the writer is trying to wrestle with a new construct. Bleak House is one where different screenplay writers start at different points,and what they choose to miss out or focus one makes it like a completely different story each time.

I've been asked about DICKENS'S TREATMENT OF WOMEN

I've been asked about DICKENS'S TREATMENT OF WOMENThere's "Urania Cottage" the home he established (with Angela Burdett-Coutts) for former prostitutes and "fallen women".

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014...

I think one of the most sympathetic, morally aware and troubled female characters he ever wrote is actually a prostitute, Nancy, in Oliver Twist.

I think Great Expectations has some quite good examples of women who are not the passive heroines we might expect. Miss Havisham is very manipulative in her lust for vengeance, even to the point of destroying the life of a little girl, Estella to fulfil her plans. Although she has been utterly hurt as a bride, and everybody feels pity for her in that respect, it seems her pride rather than her feelings have been hurt, because she has set out on a quest of revenge against all men in general. And of course Estella in turn manipulates Pip.

I remember suggesting you reading Little Dorrit, so presumably you have her example as an "ideal" Dickensian female. But thinking of other female characters in this book, how about the unpleasant and malevolent mother of Arthur, Mrs. Clennam? And also Tattycoram - Pet Meagles's adopted maid. She was perhaps more bratty, but had evil inclinations as well. Miggs is downright spiteful and conniving.

David Copperfield has a wealth of varied female characters, ranging from his aunt Betsy who is good, right through to Jane Murdstone who is evil. Rosa Dartle is also somewhat vicious - "about thirty years of age, and... wished to be married. She was a little dilapidated - like a house - with having been so long to let; yet had, as I have said, an appearance of good looks. Her thinness seemed to be the effect of some wasting fire within her, which found a vent in her gaunt eyes." Love it! And of course there's David's silly, emptyheaded first wife, Dora.

In Martin Chuzzlewit I'm never sure whether the Pecksniff sisters Cherry and Merry are also just cute and silly - perhaps misguided - or more designing.

At the moment I'm reading Nicholas Nickleby, and Mrs Squeers, the headmaster's wife, is an extremely nasty piece of work, as is her daughter, Fanny. She is spiteful, vain and snobbish, even looking down on her only friend Miss Price, because she is only a miller's daughter. This is how bright she is, "My pa requests me to write to you. The doctors considering it doubtful whether he will ever recuvver the use of his legs which prevents his holding a pen." LOL! Kate, Nicholas's sister is on the contrary very astute (much more so than Nicholas) - possibly one of the most independent and high-spirited female characters in Dickens.

Other positive strong females in Barnaby Rudge are Dolly Varden (a coquette, but very perceptive) and Emma Haredale (far more refined, but also intelligent and openly defiant when she feels she is being manipulated.)

Then there's Madame de Farge in A Tale of Two Cities, who is possibly the most evil character of them all.

These are a few strong female characters I can think of off the top of my head - there are lots more!!! But I think there are examples of different ways of being "strong". Perhaps as Victorian society limited women's range of actions in all sorts of ways, it also limited their freedom to commit gigantic acts of evil - a freedom that man could enjoy better at that time. Something to think about perhaps, although Madame de Farge was pretty much responsible for the entire uprising in the novel, which tends to work against that theory...

I've also been asked about DICKENS'S CHILDREN

I've also been asked about DICKENS'S CHILDREN Well there's Mamie - she springs to mind first! She was his second child, and called after his beloved Mary Hogarth. She never married and stayed with her father until his death. She helped to edit Dickens's letters and published two books about him, Charles Dickens, By His Eldest Daughter (1885) and My Father as I Recall Him (1896).

Then there's Charley - Dickens's first child, who was the only child who lived with his mother after Dickens's separation with Catherine in 1858. He married the daughter of Dickens' former publisher, one of the many people with whom Dickens had a falling out. Then after a failed business venture, Dickens hired Charley as sub-editor of "All the Year Round", so maybe there was a reconciliation.

The others were a bit vague in my mind - he had 8 surviving children, and they mostly lived with him after he threw Catherine out, except for Charley. So I've found a bit more out :) Here - very briefly - they are, in order of birth,

Katie - sided with her mother, and married the brother of Dickens's friend, Wilkie Collins. Dickens always felt she married to get out of the home after the separation.

Walter - became a lieutenant in the 42nd Highlanders in India, where he got into debt. He died and his debts were sent home to his father.

Francis - A month after Walter died, Francis discovered the fact as he had joined the Bengal Mounted Police. He returned to England in 1871, the year after Dickens's death. But he squandered his inheritance and emigrated to Canada.

Alfred - also emigrated - to Australia, where he remained for 45 years. Later he lectured on his father's life and works in England and America, dying in New York on a lecture tour. Apparently he had no money worries!

Sydney - joined the Navy, which pleased his father very much. But *sigh*... he got into debt, asking his father for financial aid which Dickens refused. Sydney died at sea.

Henry - was called after Henry Fielding. (All Dickens's children are called after writers or actors in part of their names, such as "Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens".) Henry was apparently the most successful of Dickens children. He became a lawyer and judge, and was eventually knighted in 1922. He also performed readings of Dickens's works and published books on his father's life.

Edward - nicknamed "Plorn" was named after the novelist Edward Bulwer Lytton. He was Charles Dickens's youngest son, and a favourite. With his father's (strong!) encouragement, Edward emigrated to Australia at the age of 16, and eventually entered politics, serving as a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly from 1889 to 1894. He died in poverty at the age of 49.

Dora - was his 9th child, who did not survive. She was born during the writing of David Copperfield and called after the main character's first wife. But the baby died at eight months old.

There are definitely recurring themes here, aren't there? And what amazes me also is how many of his children did in fact survive, in an age when infant mortality was so high.

THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOP

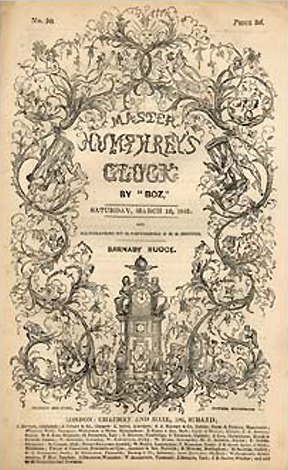

THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOPThe Old Curiosity Shop was published in 88 weekly parts between April 1840 and February 1841, in his weekly serial in his weekly serial "Master Humphrey's Clock".

I'm not actually setting out the parts and their equivalents this time, although the previous novels have their original publications dates in this thread. I usually just read however many chapters I want, though, so it's not particularly useful to break it down into the original chunks.

The serial was part of "Master Humphrey's Clock" - his own magazine which he also wrote features for, edited, and suggested and selected contributions from others writers such as Wilkie Collins and Elizabeth Gaskell. Dickens was never one to delegate! He was between 28 and 29 years old at this time.

Another thing happening in his life was that he was visiting his parents in Devon. He had bought them a house there, but they missed the London Life and wanted to be "allowed" back. His father (famously the inspiration for "Mr. Micawber" in David Copperfield) had persisted in borrowing money often using his son's famous name, and this became unbearably embarrassing for him. This was his solution.

Before the end of the serialisation, he had an eye to the next. So at the time he was in agonies over writing the scenes about Little Nell at the end, and claiming "Nobody shall miss her like I shall", he was also writing the beginning scenes of the very different, historical novel Barnaby Rudge.

Oh, and Walter, one of his sons was born in February!

How he juggled all this I have no idea...

The Old Curiosity Shop:

The Old Curiosity Shop:I started this yesterday and found it intriguing from the start. Instead of giving a lot of (it has to be said) rather dreary family history, as in the previous Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens is straight in there. In fact he has written himself into the book from the start with his unusual first sentence,

"Night is generally my time for walking"

Anyone who know Charles Dickens's life, will recognise the author from this. He used to walk for miles, and for hours on end, all over London - and often at night.

What an atmosphere Dickens has created straightaway, with his two abominable grotesques, his old musty house full of "curiosities", and the tiny "fairylike" child. And what a mystery! We are hooked right from the start by the questions the author/narrator also feels. Where does the old man go every night and why? And is he really rich?

It's very mysterious at the start, is there a benign guardian angel, establishing from the start the feeling of Little Nell as a symbol of inviolable purity?

(I've only read 3 chapters so far out of 73, so there are no spoilers here! And don't worry - I'll use tabs if I ever mention any significant plot developments.)

The Old Curiosity Shop was originally intended as a sketch for the magazine "Master Humphrey's Clock," but after he had written - and published - the first three chapters, Dickens decided to turn it into a novel.

When the reader starts the novel, the voice of the narrator, feels particularly personal. We can easily recognise him as the author himself. Then he tells us at the end of the third chapter that he is going to disappear, and from then on (presumably) we will have an omniscient narrator. The upshot of this is that for the reader, who is already feeling an unworldly sense with this novel, is put on edge even more, and feels a little disturbed... disjointed... dislocated.

OK, I'm hooked.

I've been looking into the "switch", where he tells us at the end of chapter 3 that now he's introduced the characters he will,

I've been looking into the "switch", where he tells us at the end of chapter 3 that now he's introduced the characters he will,"detach myself from its further course, and leave those who have prominent and necessary parts in it to speak and act for themselves."

The change of plan, when The Old Curiosity Shop became so popular, was to lengthen it into a novel which would then continue to be published in serial form in Master Humphrey's Clock. Later on, when published as a book, he decided not to alter anything. So we keep the different "feel" (sort of mysterious and spooky - no humour as we have in later chapters) of the first 3 chapter, with the rather unwholesome narrator, who had accompanied Little Nell home,

"It would be a curious speculation" said I after some restless turns across and across the room, "to imagine her in her future life holding her solitary way among a crowd of wild grotesque companions, the only pure, fresh, youthful object among the throng. It would be curious to find - "

I checked myself here, for the theme was carrying me along with it at a great pace, and I already saw before me a region on which I was little disposed to enter. I agreed with myself that this was idle musing, and resolved to go to bed, and court forgetfulness."

which is a very unsettling passage narrated by a sinister sort of character, who for some reason had delayed taking Nell home by the straight route. I personally wonder if Dickens might have been going to make this into a kind of ghost story, as it is so unsettling.

There is a noticeable difference and lightness of touch, starting with chapter 4. Have a look!

Dickens refers to the fact that he did not change anything it in one of his prefaces,

"Master Humphrey (before his devotion to the bread and butter business) was originally supposed to be the narrator of the story. As it was constructed from the beginning, however, with a view to separate publication when completed, his demise has not involved the necessity of any alteration."

So already we have so far, Grandfather, Nell, Kit - Fred, Dick - and the nasty Quilp. All very much like a fairy tale, complete with a troll or ogre :D

I'm planning on 4 chapters a day - but that's an aim really. I missed out yesterday as the rotten hospital took all my stuff off me and put it in a locker, leaving me to twiddle my thumbs for ages :( And I'd thought that was a prime time for reading too... LOL!

I'm planning on 4 chapters a day - but that's an aim really. I missed out yesterday as the rotten hospital took all my stuff off me and put it in a locker, leaving me to twiddle my thumbs for ages :( And I'd thought that was a prime time for reading too... LOL!I'm examining the illustrations closely, mainly because one of the versions I have seems to have an additional illustration as the frontispiece, and I cannot find mention of it online anywhere. It's signed "HKB", so is clearly "Phiz"'s". And that book is an 1892 copy of the first edition - Green's illustrations must have been a later edition I think. I'm still looking - it almost tells the whole story, and has an eggtimer prominently interwoven in the design. I'll copy it here later if I can't link it.

The first edition was illustrated by George Cattermole and Hablot Browne, with just one single illustration each from Samuel Williams and Daniel Maclise.

Because of the illustrations - the first one of Little Nell, and these words,

"I had her image, without any effort of imagination, surrounded and beset by everything that was so foreign to its nature...she seemed to exist in a kind of allegory, and having these shapes about her, ...to imagine her in her future life holding her solitary way among a crowd of wild grotesque companions, the only pure, fresh, youthful object among the throng."

I'm fairly sure in my own mind that at this stage Dickens had a sort of ghost story planned, with the narrator being somehow "psychic". That particular engraving (view spoiler). So I think it is probably meant as a portent.

I am wondering if Daniel Quilp is the nastiest piece of work Dickens ever invented! I can't think of a worse one... He's a bit like a goblin. Quilp's not even just supremely malicious, he's sort of sub-human, threatening to "bite"people all the time! Here's a description of him in his sleep,

I am wondering if Daniel Quilp is the nastiest piece of work Dickens ever invented! I can't think of a worse one... He's a bit like a goblin. Quilp's not even just supremely malicious, he's sort of sub-human, threatening to "bite"people all the time! Here's a description of him in his sleep,"hanging so far out of his bed that he almost seemed to be standing on his head, and whom, either from the uneasiness of this posture or in one of his agreeable habits, was gasping and growling with his mouth wide open, and the whites (or rather the dirty yellows) of his eyes distinctly visible."

I shall be interested to see if he has just one redeemable feature!

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

I love its passion - a diatribe against social conditions and various institutions. Yet it is still full of humour! The great thing I'm finding about reading them in order is that the stages Dickens went through become so apparent. The Pickwick Papers was just so full of fun and "larks" - the humour came through all the boisterous characters and the ridiculous situations. At times it seemed very farcical, until the time when his beloved sister-in-law (in real life) died and then the book becomes more sober, with passages set in the Fleet prison.

Oliver Twist is different right from the start. Yes, Dickens's humour is there, but it is a very black biting humour. Sarcasm and irony are on every page; it's a far cry from Pickwick! Such a contrast :)