More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

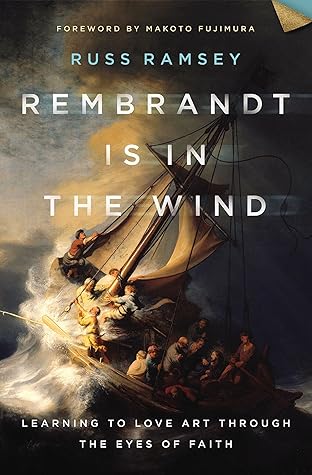

Russ Ramsey

Read between

April 18 - April 25, 2025

“Why art?” In answer to my cry, my professor wrote back in typical eloquence, “Mako, that is one of the most important questions to ask. And I would like to push you to ask a deeper question through your art and writing: ‘Why live?’ ”

By learning to truly see, we discover, one painting at a time, that the darkness within us is no longer hidden but is revealed in the light of painted countenance, guided by a shepherd meandering into museums.

“There’s nothing more genuinely artistic than to love people,” said Vincent van Gogh.

There’s so much beauty around us for just two eyes to see. But everywhere I go, I’m looking. Rich Mullins

Rather than run or hide from this humiliating series of events, he captured the moment of his greatest shame.

It is hard to render an honest self-portrait if we want to conceal what is unattractive and hide what’s broken. We want to appear beautiful. But when we do this, we hide what needs redemption—what we trust Christ to redeem. And everything redeemed by Christ becomes beautiful.

This is how we should see others and how we should be willing to be seen by others: broken and of incalculable worth.

What makes humanity so distinct from all other forms of life? Three properties of being that transcend the capacities of all other creatures, known as transcendentals, have risen to the surface: the human desire for goodness, for truth, and for beauty.

Goodness, truth, and beauty were established for us by the God who is defined by all three.

The pursuit of goodness, the pursuit of truth, and the pursuit of beauty are, in fact, foundational to the health of any community.

We are the only creatures who are consciously concerned with goodness and truth.

Creativity is a path to beauty. The creative work of naming is the work of ascribing dignity and speaking truth.

In my experience, many Christians in the West tend to pursue truth and goodness with the strongest intentionality, while beauty remains a distant third. Yet when we neglect beauty, we neglect one of the primary qualities of God. Why do we do that?

Beauty is what we make of goodness and truth. Beauty takes the pursuit of goodness past mere personal ethical conduct to the work of intentionally doing good to and for others. Beauty takes the pursuit of truth past the accumulation of knowledge to the proclamation and application of truth in the name of caring for others. Beauty draws us deeper into community.

We have a theological responsibility to deliberately and regularly engage with beauty for three reasons. First, God is inherently beautiful.

Second, God’s creation is inherently beautiful. There is beauty all around us, and it points to the glory of God.

Third, God’s people shall be adorned in beauty for all eternity.

We should engage with beauty deliberately and regularly because these are the clothes we will walk around in for all eternity.

Though we miss the point if our goal is to distill beauty down to a list of functionalities, there are real benefits to be gained from deliberately and regularly engaging with beauty.

Beauty corrects wrong general impressions by contrasting them with specific truths. The more we engage with beauty, the more we train our hearts to anticipate finding beauty, until eventually, everywhere we go, we’re looking for it.

When we engage with art, we learn about the principles of composition, design, color, and perspective. We hone our creative instinct. We get better. When we create, we reflect the image of the Creator. There is a cycle of creation here: Beauty inspires creativity, and creativity is a path to more beauty.

In Confessions, Augustine wrote, “I have learnt to love you late, Beauty at once so ancient and so new! I have learnt to love you late! You were within me, and I was in the world outside myself.”

Cultivate the habit of pursuing beauty, because, as Annie Dillard wrote, “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

Michelangelo never made any mystery of the fact that his entire life, from youth to old age, was consumed by passion.”12 Specifically, his was a passion for beauty. He was captured by it. And as it is with a great many passions, his hunger for beauty would become for him a source of torment—an appetite he could never fully satisfy, though his attempts to do so would have a corrupting effect on his soul.

As a young man, Michelangelo could not seem to shake either his faith or his carnal pursuits. This was his torment, which bore itself out in his work.

David is perhaps the most famous character in the Old Testament. Everyone knows at least part of his story. So it’s not unusual that David would be one of the early statues commissioned for the Duomo’s set of twelve. It is also not hard to imagine that Michelangelo would be drawn to the shepherd-king. David’s story and the complexity of his character as both an adulterer and a man after God’s own heart aligned, at least in some ways, with Michelangelo’s struggle between sensuality and devotion to the Lord.

Women desired him, and men wanted to be him—a poet, a theologian, a musician, a lyricist, a warrior, a lover, an architect, and a tactician. And along with all this innate ability and physical beauty, Scripture says David was also a man after God’s own heart.20 It’s hard not to envy the guy.

In a similar form of exaggeration, David stands naked and defenseless—a detail not in Scripture but included to heighten the viewer’s grasp of just how vulnerable he was against his unseen foe. The boy is naked, but he is anything but weak. The determination on his face and the weapon in his hands convey not only strength but confidence that the victory will be his. This was not a battle against flesh and blood.

The story is perfect—a perfect enemy, a perfect youth, a perfect cast of a lethal stone, a perfect ending. Michelangelo fit it all into a perfect statue of a perfect hero.

No one is perfect—not in this life. We live in a world of limits. We all run up against them, and we all have them. If you’re like me, you wish this weren’t the case and find the whole business hard to accept. But limits are a fact of life—and part of God’s design.

One of the beauties I see in this part of God’s design is that our limits and our need for others end up producing results—beautiful, helpful, unexpected results—that none of us on our own would know how to create, or even think to create.

We work with what we’re given. None of us build on an untouched foundation. Many people and their many decisions—for better or worse—have played a role in determining where our feet are planted. And the chances are good that we are each shaping some aspect of a foundation on which someone else will one day stand.

Living with limits is one of the ways we enter into beauty we would not have otherwise seen, good work we would not have chosen, and relationships we would not have treasured. For the Christian, accepting our limits is one of the ways we are shaped to fit together as living stones into the body of Christ. As much as our strengths are a gift to the church, so are our limitations.

We are drawn to beauty, and we instinctively know that somewhere, somehow, such a thing as perfection exists. We seek both beauty and perfection, at great expense of money and time. Beauty we can find. It’s all around us, in a million different forms. Perfection, on the other hand, eludes us.

It is as though, to borrow an expression attributed to Meister Eckhart, perfection inhabits our true home, but we are walking in a distant country. We are like revenants. On the other side of the veil is the tangible glory of unfailing perfection, but it is just out of our reach.

It is important to remember this if we want to understand the way Jesus loved sinful people. He loved them knowing their lives were riddled with problems. And the way he welcomed them did not always immediately deliver those people he loved from the complications of their choices.

This is why so much of the art from Europe in the Middle Ages, before photography or widespread travel, depicted biblical narratives in a European context. Much of the architecture, clothing, technology, and even skin tones of biblical characters—Jesus included—looked European to emphasize that the story of Scripture applied to people in their context. Depicting Jesus as he actually was—a Middle Eastern, dark-skinned Jew—wasn’t a value at that time because the goal of art wasn’t historical accuracy; it was accessibility. This is why so many European paintings of biblical stories from that time

...more

Caravaggio tells the sacred story by way of emphasizing the profane, stunning viewers with his intensity and directness. He didn’t want to make art that was only meant to be glanced at. He wanted to create a visceral experience for his viewers—something that would stop them, trouble them, or arouse whatever might be sleeping in their souls.

He wanted to leave room for ambiguity, doubt, and sorrow. He wanted the simple difficulty of living in this world to be written on his subjects’ faces.

The Calling of St. Matthew was one of Caravaggio’s most important paintings because it established him as a master. Matthew was a paradox—a sinner who made his living taking from others and also a man who left everything to follow Jesus. Caravaggio was drawn to these life-changing moments in Scripture,

When he was in the throes of despair, desperate, and afraid for his life, he created these two works that tell the story of the birth of the tender Savior who grew into a man who wept over suffering, sickness, and loss while demonstrating his power over death itself. This is the paradox of Caravaggio—he brought so much suffering on himself, with such bravado and acrimony, yet when he picked up his brush, the Christ he rendered was the Redeemer of the vulnerable.

Caravaggio knew what it meant to be pursued—to live so violent an existence that this world would come to give no quarter to one like him. He knew what it was to have the ability to render beauty that could bring a person to tears and yet remain unable to live free from his own destructive behavior.

Caravaggio’s art reveals a man who seemed to listen to Jesus in some way.

We know that while he was yet sinning, he was producing some of the most profoundly merciful and eloquent commentaries on Scripture ever painted.

Caravaggio’s life reminds us that we who embody the sacred and the profane have an enormous capacity to hurt each other. Caravaggio lived a destructive life. But his art shouts into that chaos that just as Christ could call the tax collector to follow him or draw from the recesses of the hardest heart the beauty and wonder that poured out of Caravaggio between his seasons of Carnival, our Lord’s capacity to extend grace is greater still. And grace transforms even the hardest hearts.

We don’t think much about our mortality, but the question is never far away. It comes in an instant and often brings with it an inherent sense of reverence. Life is a fragile, sacred thing.

“Do not weep,” he said. His words were tender, but words alone would not stop these tears. They both knew this. Still, Jesus interrupted her mourning long enough for her to look up and see his compassion for her.

The peace he has brought by his resurrection is neither myth nor fantasy. It is an inheritance that will never perish, kept for those who believe, world without end.29 His is a kingdom that will live. But it is the only one of its kind.

Though we’re told that God made the world, we’re not really told how. He spoke, and things came into being. Surely that sentence spreads out like an umbrella over an unfathomable amount of specificity.

Rembrandt produced what he did because he studied Caravaggio. Van Gogh studied Rembrandt. And nearly every artist of note in the last hundred years has studied all three.