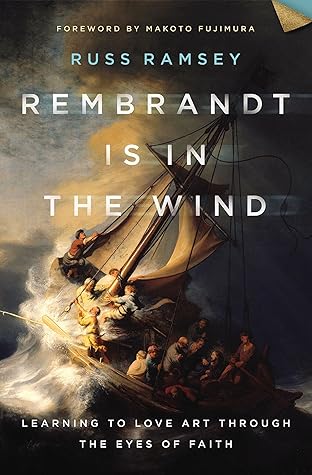

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Russ Ramsey

Read between

April 18 - April 25, 2025

Painting is not just an art, but a science. It is an achievement not only in beauty or emotion or color, but in math and geometry and light.

Vermeer’s potential to render almost anything in the world with a kind of photo-realism unseen by those of his generation seemed limitless. So, what did he choose to paint? What would be the subject matter of his artistic vision? He chose the most dignified thing in the world: people in a room doing ordinary things. And to what effect? Awe.

In a letter to his brother Theo, Vincent van Gogh wrote, “A good deal of light falls on everything.”29 Seeing is as much of an art as it is a physiological ability. There is skill involved.

The concept of learning to see became a guiding principle for both science and art. The idea gained popularity in the 1700s during the scientific revolution, but the concept was certainly not new.

Leonardo da Vinci’s “principles for the development of a complete mind,” written two hundred years earlier, stated, “Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses—especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

Vermeer “disposed these simple elements, in a few pictures, to say what he wanted—however elusively—about the subjects for which he really cared: domestic routine, the love of men for women and fathers for daughters, the consolations of music, the worlds of science and scholarship, his own profession and its ambitions—all captured in his room within a room, his camera in a camera.”

We are created to make things, so we do. But we never truly work alone.

When we stand before a Vermeer, we are seeing not only his work, but also the work of all these others and many more. Everything we make, in some measure, relies on the help of others. All of us rely on borrowed light. Even the blind composer sits at a piano not made in darkness.

There is only one who can make something from nothing: God. The rest of us sub-create. We work with what can be found lying around on the floor of creation and repurposed from the belly of the earth and the salvage

heaps of industry. In this sense, human beings are, as a species, “found object” sculptors. Even the light we work by is borrowed. The q...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By light we do our work. By that same light others behold it. And all of the light is borrowed from God.

His paint palette looked like a work of art itself.

Much of the work involved in being an artist lies in the discipline of practicing the fundamentals of the craft. Artists must master the rules of composition if they want to break them well.

The French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote, “Delacroix was passionately in love with passion, but coldly determined to express passion as clearly as possible.”2 Delacroix rendered this passion not through a pandering sentimentality, but through the discipline of sound technique. He learned to create works that captured onlookers with their sensuality, but also with their precision.

Since the dawn of boyhood, ferocious beasts and beautiful women have been subjects of great fascination, carefully studied, committed to memory, and revisited as often as discretion allows. Bazille had not only seen Delacroix’s lions and women; he had internalized them. He did what we do with art. He stored them away in his memory and carried them in his mind as a part of his own personal collection.

Claude Monet, perhaps best known for his water lilies, worked largely in plein-air landscape painting, favoring natural settings over Renoir’s social situations involving people. He, too, was one of the fathers of Impressionism.

For want of a title in an exhibition catalog, the name “Impressionism” was born. Critics did not intend the name as a compliment. Many of them used the term to describe an emerging line of art that seemed to them undisciplined and unfinished.

As it goes with most new creative expressions, people usually need some time to warm to the idea of things being different from what they’re used to. And that season of warming is often punctuated with reactions of cynicism and snark by those called upon to critique it.

Art held Bazille’s attention, and in 1864, Bazille failed his medical exams and turned to painting full-time.

He knew how to make and sell art to fund his craft, but he also knew, as every working artist must learn, that his was a vocation of feast and famine.

Stop for a moment to consider what was happening in this little studio. No less than seven of the world’s most celebrated painters gathered to work on their craft, but even more, to be part of this community of artists. They shared a common perspective on where they believed art was going, which Bazille summarized by saying, “The big classical compositions are finished; an ordinary view of daily life would be much more interesting.”8 These artists were testing new waters, trying new techniques, hoping to introduce something new into an area of culture known for resisting and even scoffing at

...more

It was imperative for these artists to work in community, not in isolation. They needed one another. They needed to be around each other. They needed to be able to share a common space—a place where they could gather and speak freely. A place where they could show what they were working on to get feedback, encouragement, and pushback. They needed voices that understood what they were trying to do. They needed assurance that they were not fools. And if they were in fact fools, they needed to be a tribe of fools together. They needed a place, and that’s exactly what Bazille gave them.

In Bazille’s Studio; 9 rue de la Condamine, there is no apparent hierarchy, no apparent leader. Just people who labored together in the pursuit of using their gifts to accomplish something meaningful.

I wonder about uninterrupted potential. We live in a world of limits. The full range of “all that could be” is not offered to any of us in this life. Michelangelo had to work from a precut stone; Caravaggio could not balance his artistic talent with his carnal appetites; Vermeer was constrained by financial limitations and an early death; and Bazille fell in battle when he was still young.

Every one of us faces limitations of many kinds. This should not surprise us.17 Every one of us must make certain choices in life that take other options off the table. Of course, this isn’t always a negative—we choose one spouse at the exclusion of all others.

We take a job east of the Mississippi, making it impractical to stay connected to what’s happening on the West Coast. Work and parenthood begin to chip away at the time we were once able to devote to some creative or athletic passions, and we lay those inte...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

We live in communities that need goodness, truth, and beauty. And we play a role in advancing those transcendentals that make us human. We are to curate them for others. We play a role in blowing on the embers of “whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable.”19 Whatever is excellent or praiseworthy, think about such things—and be a part of them.

Who knows what could happen?

Imagine Vincent van Gogh in the last year of his life. See him buying his art supplies, mixing his colors, preening his brushes, stretching and preparing his canvases. Imagine his sketches, like recipes, lying faceup on the table next to the easel. Imagine the eternal bits of color under his fingernails, on his beard, and deep in the seams of his clothes, his person an accidental painting in the same spectrum as the canvas of the day. The pace and nature of his craft immerse him in a sensual world of color, shape, texture, scent, and composition. It is hard to tell where the man stops and his

...more

Many who see The Red Vineyard at the Pushkin Museum and neglect to read the plaque on the wall beside it might never realize they are looking at the only one of his paintings anyone ever purchased while van Gogh was alive.

Coming from Holland, Vincent was fascinated by the vendage. There was something settling about the rhythm of the ingathering—humanity and land in harmony. People worked and enjoyed a return on their labor.

Seurat believed knowledge of how the eye and the brain communicated with each other could be used to create a new language of art based on the arrangement of hues, color intensity, and shapes—that there was a scientific reason that art seemed to speak to the soul.

Ordinary scenes of everyday objects moved Vincent. He wrote, “Even though I’m often in a mess, inside me there’s still a calm, pure harmony and music. In the poorest little house, in the filthiest corner, I see paintings or drawings. And my mind turns in that direction as if with an irresistible urge.”

Vincent believed that although his use of vibrant color made his paintings appear less realistic, it helped the paintings come alive. And the many people who have viewed his paintings since would agree. Somehow, color, composition, and subject matter combine to connect with people in ways that defy explanation. This is the mysterious, transcendent quality of art—something in the liniment oil and pigment breaks through the plain of the canvas and penetrates the human soul in a way that suddenly and inexplicably matters.

This transcendence is what compels a tourist in a museum to circle back to a particular painting she encountered that day for one last look before she leaves. She may not be able to say why, but she feels she must return. So she does. And feeling as though she is forcing a sort of disconnection when she at last pulls herself away, she vows to remember the piece—to carry it with her in the recesses of her heart. And she does. The work never again appears to her as an ordinary piece of art, but as part of

her own collection. When she saw the work the first time, it belonged to the world. But by the time she leaves that i...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Some people carry with them entire collections of Renaissance-era masterworks by Rembrandt and Vermeer. Others can close their eyes and revisit the Impressionists of Paris: Monet, Manet, and Bazille. For others still, line after line of Scripture or Shakespeare effortlessly unfold from the recesses of memories dating back to when th...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This is the intangibility of genius—to create work that transfers from the canvas, the page, or the instrument into the heart of another person, arousing a longing for beauty and an end to sadness. This was what Vincent wanted to create—art that would transfer from his eas...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Vincent’s motives were not solely devoted to the work he produced. He craved recognition deeply. He wrote, “I can do nothing about it if my paintings don’t sell. The day will come, though, when people will see that they’re worth more than the cost of the paint and my subsistence, very meagre in fact, that we put into them.”13 His lack of commercial success discouraged him, as it would anyone who worked at something for the better part of a decade, believing it was their life’s calling without ever making a dime.

Though Vincent longed to be recognized for his genius, he was a paradox when it came to receiving it. The adulation of the public proved to be more than he could bear. When Vincent read Isaacson’s complimentary article, he was embarrassed by the attention and asked Isaacson never to write about him again.

Vincent’s growing acclaim was not happening in a vacuum. He was part of a movement. Still, he stood out. One reason he became the face of Postimpressionism was because his work most acutely displayed the characteristics of that era—thick paint application, vibrant colors, geometric compositions, and distorted details. He employed them all. And as it happens with any artist on the leading edge of a new era, many embraced his work as exciting and refreshing, but others rejected it as being inferior work born of youthful swagger with no respect for the discipline of the craft.

Vincent had no idea any of this happened because he was not there. He did not know these artists he admired had risen to defend his honor and validate his brilliance.

But Maus and his group were interested in art that would inspire new conversations, not just satisfy commercial appetites. And Vincent’s work did just that. His paintings went on to be among the most discussed at the Expo.

Rembrandt produced roughly six hundred oil paintings during his career, which spanned more than forty years. Claude Monet, van Gogh’s contemporary, painted around 2,500 paintings over the course of sixty years. Paul Cézanne painted nine hundred canvases over forty years. On average Rembrandt completed fifteen canvases per year; Monet, forty-two; and Cézanne, twenty-three.

Over the first half of his painting life, from 1881 to 1884, Van Gogh averaged twenty-one paintings per year. But between 1885 and 1889, the second half of his career, that number jumps up to 130 canvases per year. That works out to one complete painting every three days for five years straight.

VAN GOGH’S OUTPUT BY YEAR OVER THE COURSE OF HIS PAINTING CAREER The monthly breakdown of his output in 1890 is even more startling. Between January and April, he painted just eighteen paintings total, which means he could not have done much the following three months besides eat, sleep, and paint.

Imagine Vincent in those last months of his life. See him mixing his colors, stretching his canvases, and preening his brushes. See the eternal bits of color under his fingernails, on his beard, and in his clothes in the same spectrum as the fury of those three months, during which he completed an average of one canvas every single day. Now add in the 2,140 other watercolors, sketches, prints, and letters he composed during those nine years, and we’re left with a heartbreaking picture: Somewhere in that flurry of motion between painter and canvas was a man held captive by an insatiable

...more

Perhaps Vincent summarized his struggle best when he said, “If we’re tired isn’t it because we’ve already gone a long way, and if it’s true that man’s life on earth is a struggle, isn’t feeling tired and having a burning head a sign that we have struggled?”

What are we to make of Vincent’s story? What of the futility that seems to belong to any creative endeavor? Vincent said, “Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke.”

C. S. Lewis wrote, “The sense that in this universe we are treated as strangers, the longing to be acknowledged, to meet with some response, to bridge some chasm that yawns between us and reality, is part of our inconsolable secret.”