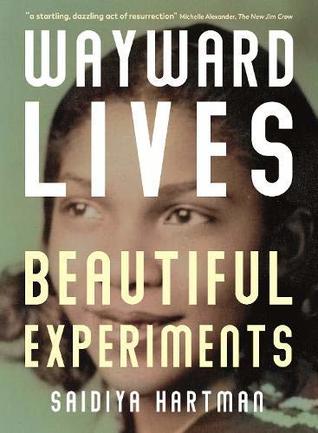

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 25 - August 27, 2020

Few, then or now, recognized young black women as sexual modernists, free lovers, radicals, and anarchists, or realized that the flapper was a pale imitation of the ghetto girl. They have been credited with nothing: they remain surplus women of no significance, girls deemed unfit for history and destined to be minor figures. This book is informed by a different set of values and recognizes the revolutionary ideals that animated ordinary lives. It explores the utopian longings and the promise of a future world that resided in waywardness and the refusal to be governed.

The wild idea that animates this book is that young black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.

starvation wages.

companionate marriage

gender-queer stroller,

In the slum, everything is in short supply except sensation.

Is cotton so different than silk and not as pretty draped like a banner across the streets?

A whole world is jammed into one short block crowded with black folks shut out from almost every opportunity the city affords, but still intoxicated with freedom.

Each new deprivation raises doubts about when freedom is going to come; if the question pounding inside her head—Can I live?—is one to which she could ever give a certain answer, or only repeat in anticipation of something better than this, bear the pain of it and the hope of it, the beauty and the promise.

The photographs coerced the black poor into visibility as a condition of policing and charity, making those bound to appear suffer the burden of representation.

In the hallway, you wonder will the world always be as narrow as this, two walls threatening to squeeze and crush you into nothingness.

know firsthand that how we live and where we stay is not a social problem. It is our relation to the white world that is the problem.

Is it apparent that her life is disposable?

Her body is exposed, but she withholds everything. “The body shows itself,” complying with the demand, yet “it does not give itself, there is no generosity in it.” Is it possible to give what has already been taken?

By age ten, had she learned everything about sex she would ever need to know? By twelve, had she no interest in it?

forensic picture of an act of sexual violence not deemed a crime at all.

Beauty is not a luxury; rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.

Mattie’s restiveness and longing and the free love practiced in a private bedroom rented by the week were part of a larger ensemble of intimate acts that were transforming social life and inaugurating the modern, which was characterized by the entrenchment and transformation of racism, emergent forms of dispossession, and the design of new enclosures, and by a fierce and expanded sense of what might be possible.

Mattie has been credited with nothing, deemed unfit for every role except servility, condemned in advance of wrongdoing, and destined to be a minor figure even in her own verified history.

There was a thin line between loss and expenditure, between yielding and breakdown.

Some men hurt a woman by the cruel things they do or say; Earl hurt Caroline by all things he withheld.

He did not yet know whether he was a good man or a bad one because he hadn’t been tested.

Mattie had little regard for private property. Mine, I own it, belongs to me—were terms that didn’t carry much weight with her.

She treated possession as if it were conditional, rather than absolute, as if beautiful objects were intended to be shared, as if the loveliest things were rightly a communal luxury.

To be handled by men, to be manhandled, to be seized by men, to be used by men, to be used up by men.

the submission enjoyed by the one who chose it, a reckless act of self-expenditure.

Over the next two decades, the Negro quarter would become the ghetto—a racial enclosure, an open-air prison.

“He took care of me and my children, so I have every right to use his name.”

Crime, he believed, was the result of misdirected intelligence under severe economic and moral strain, failing to see that crime was the necessary outcome of racial policing and essential to the remaking of a white-over-black social order.

On a night like this, all conspired to escape the suffocation of tenement flats, airless back bedrooms and sweltering buildings, to flee the assault of rank bodies, crying babies, embattled couples, and to shake off the general misery.

Just get a law passed that everyone must go nude. Then you’d get not equality but Negro superiority.”

their reproductive capacity and maternity was also targeted and deemed the property of slave-owners; the womb was made into a factory and children transformed into commodities for the market.

placed black females on the threshold between the dangerous and the unknown.

Were they unnecessary, expendable, or without value? When weighing the danger they presented against the value of their lives, was it a matter of who they loved multiplied by how many times they had loved divided by the losses of death and separation?

lovely actuality of blackness.

Waywardness is an ongoing exploration of what might be; it is an improvisation with the terms of social existence, when the terms have already been dictated, when there is little room to breathe, when you have been sentenced to a life of servitude, when the house of bondage looms in whatever direction you move.

It is the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.

With human nature caged in a narrow space, whipped daily into submission, how can we speak of potentialities

Mere survival was an achievement in a context so brutal.

It was difficult to elude the state when servility and confinement was the script into which you had been cast.