More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 4, 2020 - March 1, 2021

It is to acknowledge that we were never meant to survive, and yet we are still here. The entanglement of violence and sexuality, care and exploitation continues to define the meaning of being black and female.

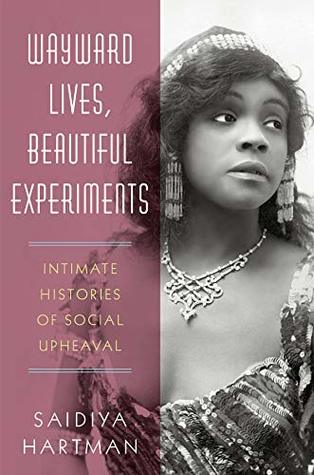

In the pictures anticipated, but not yet located, we are able to glimpse the terrible beauty of wayward lives. In such pictures, it is easy to imagine the potential history of a black girl that might proceed along other tracks. Discern the glimmer of possibility, feel the ache of what might be. It is this picture I have tried to hold on to.

I envisioned her not as tragic or as ruined, but as an ordinary black girl, and as such her life was shaped by sexual violence or the threat of it; the challenge was to figure out how to survive it, how to live in the context of enormous brutality, and thrive in deprivation and poverty.

Beauty is not a luxury; rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.

If it is possible to imagine Mattie and other young black women as innovators and radical thinkers, then the transformations of sexuality, intimacy, affiliation, and kinship taking place in the black quarter of northern cities might be labeled the revolution before Gatsby.

Octavius Catto, a young teacher and civil rights activist, had played a central role in the campaign to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment in Pennsylvania. In the election of 1871, he and other black men exercised this hard-won right in a vote for the Republican Party. After casting his ballot in Philadelphia, he was murdered by an Irish mob deputized by the police.

Ten percent to twenty-five percent of the unions in the slum were common-law marriages, temporary cohabitation, and liaisons that lasted for two to ten years. Such kinship was labeled broken and immoral, and the home environment deemed unhealthy and a danger to society. Women assumed the duties of men, and men were dependent on the wages of their sisters, mothers, and wives to support families. Men searching for work left partners and children behind, started new families elsewhere, and acted as substitutes for other men gone missing. Perhaps an aunt or lover or lodger did the same for him,

...more

Sixty percent of the black population was under thirty years of age. The tendency to marry later, economic distress, the high death rate of black men, and changing sexual mores were revolutionizing black intimate life. Women outnumbered the men.

Three decades after Emancipation, freedom was an open experiment.

In the 835 hours of conversation with five thousand people in the ward, they asked, Why are you studying us? Wouldn’t it be better to study white folks, since they are the ones who need changing? They wondered what Negro was earnest or naive enough to believe that truth alone would change white people? As if they were blind to the world they had created? Or didn’t know no better than to treat Negroes like dogs? We ain’t specimens!

Withholding and stony silence often circumvented the relay of questions. Had the interviews been recorded, we might expect to hear such evasions: “Husband? Which one?” “Why does it matter what the law say, isn’t it how you live that counts?” “He was my husband though we didn’t have any paper. We have morals just like everybody else.” “He took care of me and my children, so I have every right to use his name.” “A widow. I don’t know when, but I’m sure that he’s dead.” “No, I didn’t know my father. It was my mother who put the food in my mouth.”

It hurt him—the sight of all these young people prevented from stepping any higher than their mothers and fathers and forced to earn their bread and butter by menial service. They were bitter, discontented, and refusing to work because barred from their chosen vocations. Who could blame them for rejecting servitude, for their unwillingness to pretend that being conscripted to manual labor was opportunity? Who could blame them for declining to be trained for servility?

Crime, he believed, was the result of misdirected intelligence under severe economic and moral strain, failing to see that crime was the necessary outcome of racial policing and essential to the remaking of a white-over-black social order.

One is not compelled to discuss the Negro question with every Negro one meets or tell him of a father who was connected with the Underground Railroad; one is not compelled to stare at the solitary black face in the audience as though it were not human; it is not necessary to sneer, or be unkind or boorish, if the Negroes in the room or on the street are not all the best behaved or have not the most elegant manners; it is hardly necessary to strike from the dwindling list of one’s boyhood and girlhood acquaintances or school-day friends all those who happen to have Negro blood, simply because

...more

Jane Addams. The “newly awakened senses” of urban youth were attracted to “all that is gaudy and sensual, by flippant street music, the highly colored theater posters, the trashy love stories, the feathered hats, the cheap heroics of the revolvers displayed in the pawn-shop windows.” The untutored longing for beauty was dangerous because it was “without a corresponding stir of the higher imagination.”

I am here. She “demanded attention to the fact of her existence; she was ready to live, to take her place in the world.” Two young colored women longing after a pair of men’s shoes were guilty of the same—the ardent desire to live, the hunger to find a place in the world in which they were not relegated to the bottom.

Colored girls, too, were hungry for the carnal world, driven by the fierce and insistent presence of their own desire, wild and reckless. Most were determined not to sell anything, but content with giving it away.

She wished the men had been there.

Most would bite their tongues rather than speak out of turn to a white woman. She thought she could trust the men, but not the women.

They were too much together, too much at home, and they loved to talk and gossip. She found knots of women in the yard, and whatever she did was sure to bring about some discussion—alone they were amenable, but en masse far from it.

conquered

Did he not have enough spunk or did he have too much courtesy to fend off the attack?

These calculated acts of kindness were not enough to bridge the gulf between poverty and the minimal requirements necessary to live. None of these stopgap measures afforded a way around the truth: more than sixty percent of the Negroes in the city lived in a state of poverty.

When they withheld their recognition and made plain that they had no clear need of her, when she was unable to find her better self reflected in their eyes, when their hostility was so piercing it threatened to crush and destroy her, then the cluster of women assembled in the yard on a late August afternoon involved in the mundane tasks of hanging clothes, cracking pecans, and tying off buttons collapsed into a faceless them, a threatening crowd, a race without distinct features or characteristics. At such moments, Helen could see only treason en masse, the lines of battle were drawn; she

...more

The first generation after slavery had been so in love with being free that few noticed or minded that they had been released to nothing at all. They didn’t yet know that the price of the war was to be exacted from their flesh. People were too busy dreaming of who they wanted to be and how they wanted to live and the acres they would farm, and searching for the mother they would never find, wondering what happened to their uncle, was their sister dead, and was it true that someone had seen two of their brothers as far north as Philadelphia?

Freedom was the promise of a life that most would never have and that few had ever lived. But who could bear this?

Helen knew everything now, and she would ask them to vacate the apartment, giving them a

week’s notice, as was her usual practice. If he knew the law allowed three months, he might insist on taking it. Helen counted on his not knowing this or surmising the limits of her authority.

The daily racial assaults and clashes in downtown, coupled with the availability of housing in Harlem, spurred this migration within the city. By 1915 at least eighty percent of black New Yorkers lived in Harlem. The numbers steadily increased despite the attempt of “The Save Harlem Committee” organized by Anglo Saxon Realty to stanch the flood of black folks.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Mary White Ovington

For nearly a year she had observed first-hand this anomalous, yet beautiful, world by dwelling within the thick precincts of black life. Idle men and female breadwinners blurred the lines between man and woman, husband and housekeeper, spouse and lover.

to “a mass of humanity approximating that of the slaver’s ship.” The apartments were “human beehives, honeycombed with little rooms thick with human beings.”

In 1910, John Rockefeller Jr. commissioned a door-to-door survey of prostitutes in the worst dens of the city. Irish, French, German, and Italian women selling hand jobs and French style lived in close proximity to black working girls. Had they uttered good day, had they been willing to cross the color line, had they imagined Negroes as neighbors, they might have sounded a whore’s Internationale. This was the very thing that

Rockefeller and other Progressive reformers feared—the promiscuity sociality of the lower ranks, love and friendship across the color line.

Law and order depended on the color line to segregate vice and quarantine it within the black ghetto. The white working class fell...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The beauty of the Black Belt, whether in the Lowndes County, Alabama, or Jamaica or the tenement districts of New York, was unmistakable, and at night, despite the assault of electric lights that dimmed the stars, there was “the laughter of men and women returning from the theatre, or some dance that last[ed] until dawn. Light and intermittent noises, the heat of the long day climbing up from the pavement, this [was] the night at San Juan Hill. The plantation songs sound[ed] in the night, melodious, quavering: ‘All the people talking about heaven ain’t going there.’

“It’s strange but I sometimes think the more trifling the man, the more he is sheltered and cared for, and you will see the same love given to a selfish woman,”

him—as a holdover of the plantation and as a kind of prostitution.

This capacity to share all they had and expect nothing transformed private homes into places of refuge that welcomed all, indifferent to judgments regarding who was worthy and who was no-good.

“to slave for some trifling colored man as though you were back in the cotton field, there is a great deal of this among the women inside these doors.”

Half a woman announced the black female’s failure to realize the aspirations of womanhood or meet the benchmark of humanity.

“The Negro comes north and finds himself half a man. Does the woman, too, come to be but half a woman? What is her status in the city to which she turns for opportunity and larger freedom?”

The black woman was a breadwinner—this was the most glaring problem. In short, she threatened to assume and eclipse the role of the husband. As early as 1643, black women’s labor had been classified as the same as men’s.

The failure to comply with or achieve gender norms would define black life; and this “ungendering” inevitably marked black women (and men) as less than human.

A woman who didn’t need a man or depend on one raised concerns and instigated doubts about her own status—was she a woman at all?

When she described her black female neighbors as immoral, if she felt the pang of hypocrisy or the sting of such judgment as it redounded on her own life, she never let on.