More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

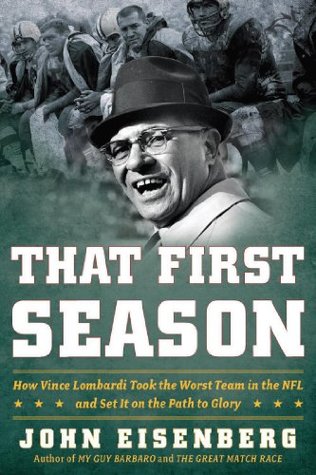

That First Season: How Vince Lombardi Took the Worst Team in the NFL and Set It on the Path to Glory

The game had been sold out for more than a month, with all but a few of the 32,500 tickets in the hands of Packer fans

Even though the Packers had won four exhibition games, Sports Illustrated and Sport magazines had still picked them to finish last in the Western Division—they had so far to climb. Even the ever-optimistic Press-Gazette had predicted they could win “three or four games, maybe more.”

Cruice was a former Northwestern halfback whose job, since the early 1950s, was to study Green Bay’s next opponent and prepare a report.

Starr, despite having been relegated to the bench, had studied film of the Bears—more than McHan—and made several astute suggestions. As always, his intelligence and work ethic impressed Lombardi.

Years of losing hadn’t dulled Green Bay’s love for the Packers, especially early in a season, before the losses started piling up.

The Lumberjack Band, a flannel-clad marching band that had played at Packer home games since the 1920s, played a brief show.

A statistical crew, composed of moonlighting Press-Gazette business and news reporters, got ready to chart the game.

At one time Halas had valued nothing more than a victory over Curly Lambeau, but the heat had gone out of their games since the Packers fell apart, and as much as Halas craved victories, he was a businessman first, and bitter games between the Bears and Packers were good for business. They made news, sold tickets, made seasons more interesting. Halas wanted the fire back in the rivalry. In 1956, when the Packers were campaigning to win funding for their new stadium, he had stumped on their behalf just before the election. More recently, when Packer president Dominic Olejniczak had asked him to

...more

The Packers had worn an assortment of different uniforms in the 1950s, seemingly unable to find a design they liked—navy blue jerseys with faded gold pants; all-white tops and bottoms with a single navy stripe down the side of the pants; and recently, dark bluish-green jerseys with three gold bands on the ends of the sleeves. Lombardi had gone with dark forest green jerseys with gold and white stripes on the ends of the sleeves, white numerals, and gold pants and helmets.

The cheers were so loud the stadium’s concrete underpinnings vibrated.

Partaking in a Packer tradition seldom seen in recent years, the fans counted down the final ten seconds and threw their programs and seat cushions into the air when time expired.

As Lombardi walked away, Lew Carpenter and Emlen Tunnell picked him up and ran toward the locker room with him on their shoulders.

The Packers had played hundreds of games over the years and won a half-dozen championships, but no one could remember their coach being carried off the field.

He had been miserable when Notre Dame went 2–8 in his senior season and the Packers won just four games in his first two years.

The players had the day off, and he and Max McGee headed to Appleton, twenty-five miles south of Green Bay, for an evening of fun. Since Lombardi had declared their favorite Green Bay haunts off-limits, they had to leave town to shake loose in their customary style.

And unlike Scooter McLean, he didn’t walk to the Northland Hotel to absorb a noontime grilling from the executive committee. Those days were over. Although Lombardi had only been in charge for one league game, it was laughable to think of him being second-guessed in such a way. The committee wouldn’t dare.

When the players came to practice on Thursday, they found a paper tacked to the locker room bulletin board. Lombardi had posted their individual grades for the Chicago game.

Players who graded above certain levels or made big plays would get paid, in cash, out of Lombardi’s pocket. Ten dollars for a quarterback sack or a thirty-yard run. Twenty when a guard made his block on 60 percent of the running plays and 85 percent of the passing plays—65 percent and 85 percent for tackles.

Lions were stunned; they had won fifteen of their last eighteen games against the Packers, usually by a wide margin,

The fans again went through their happy ritual of counting down the final seconds and tossing their programs and seat cushions into the air.

Nothing electrified Green Bay like a Packer victory. The town would be hopping.

The few hundred tickets that had not been sold went quickly; a third straight sellout crowd of 32,150 would be on hand.

The assistant coaches left town after practice on Fridays to scout a college game the next day, flying back to Green Bay late Saturday night in time to get up and coach the Packers on Sunday.

Marie felt responsible for the assistants’ wives; her husband had brought their husbands to town. Knowing they would be alone on the Saturday before the San Francisco game, she invited them over for lunch with their young children.

Like a golfer attempting a wedge shot, he dug up a small divot as he brought his leg through, taking up too much grass. The ball sailed into the twenty-mile-per-hour crosswind toward the uprights, but it lacked the necessary thrust. The wind pushed it to the right and it fell short of the end zone.

Three weeks into the season, the Packers were the NFL’s last-remaining unbeaten team.

In the locker room he was told that NFL commissioner Bert Bell had suffered a heart attack and died while watching the Eagles in Philadelphia.

Miller hosted popular television and radio shows about the Packers during the week.

Red Hickey, still frustrated about the 49ers’ loss that Sunday, told reporters he expected the Rams to beat Green Bay, as they had in twenty of the past twenty-six games between the teams. And oddsmakers in Las Vegas favored the Rams by four points even though the Packers were undefeated and playing at home. Clearly the Packers had doubters.

They had played eighteen games at County Stadium since it opened in 1953, with the average attendance a disappointing 23,038. Sports fans in Milwaukee were more excited about their own winning baseball team than Green Bay’s losing football team. But the 1959 baseball season was over, the Braves having failed to win a third-straight National League pennant—they had finished second, two games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers—and the Packers hoped their surprising start would bring out more spectators. Tickets sold briskly during the week, the total surpassing 23,000 on Wednesday, 28,000 on Friday,

...more

Lombardi and Gillman were both Earl Blaik disciples (Lombardi had taken Gillman’s spot on Blaik’s staff when Gillman left Army to become the head coach at the University of Cincinnati in 1947) and had many mutual friends.

The fans headed for the exits. The stands were nearly empty by the final minutes.

SINCE THE MERGER between the NFL and All-America Football Conference in 1950, the Packers’ league-season schedule had followed the same pattern every year. They played most of their home games early, before the weather in Wisconsin turned nasty, and spent most of the rest of the season on the road, ending with a game at Detroit on Thanksgiving and a December trip to California to play the 49ers and Rams.

In other words, it wasn’t unusual for them to begin a season respectably but then fall apart.

The players walked out of the film room shaking their heads. This guy was unpredictable, to say the least. Sometimes you just wanted to slug him, but other times he inspired you to dig down and play harder.

You could tell which players had spent Monday night in Appleton’s bars and clubs. They were throwing up.

It was too bad Starr was so quiet, polite, and mistake prone, Lombardi thought. He could really think his way through a game.

Unitas never blamed Symank, but local fans believed the Green Bay player had delivered a cheap shot, and now held up signs reading, “We Want Packer Blood.”

He remembered the Packers and Giants playing NFL championship games in the late 1930s and early 1940s, when he was coaching at St. Cecelia’s. The rivalry had diminished with the teams now in different divisions, but it was still a couple of old lions.

A loyal team guy and military officer’s son, Starr believed in the chain of command; you didn’t second-guess your coach, especially one as shrewd as Lombardi.

A winter-like storm blew through Green Bay, leaving eight inches of snow on the ground on November 3. Lombardi arranged for the team to practice indoors, at the Brown County Veterans Arena, where the floor was being cooled for an ice show later in the week. The players pushed banks of portable bleachers out of the way to clear the floor, and then ran through plays wearing tennis shoes.

Around town, as the fans dug out from the snowstorm, they discussed the Packers, their secular church.

The Packers hadn’t beaten the Bears in Chicago since 1952, and hadn’t swept the teams’ yearly home-and-home series since Don Hutson’s rookie season in 1935.

When their bus pulled up to Soldier Field, they were greeted by the Lumberjack Band, the flannel-clad City Stadium music group, which always attended the Bears game in Chicago.

After Starr completed a short pass to Taylor, the Bears’ Bill George slammed the quarterback to the turf, bloodying Starr’s lip. That should take care of you, Bart Starr, you little pussy. Jerry Kramer couldn’t believe what he heard next. Fuck you, Bill George, we’re coming after you. Kramer had never heard Starr curse. (And never did again.) They had been teammates for a year and a half, but Kramer thought of Starr as methane gas—odorless, colorless, tasteless, having little impact on his surroundings.

For the first time in Packer history, the team was flying from Chicago back to Green Bay instead of taking a train.

Asked by reporters about the decision to start Starr, the coach shrugged and said, “There’s not much to choose between him and Francis. Perhaps Francis has a little better potential. Starr is smarter.”

Starr could grasp complex material, play well at times, and was the nicest young man, but he walked around under a dark cloud. Receivers dropped his best passes. The ball mysteriously slipped out of his hand at the worst time. Something always went wrong.

the Packers again moved their practices indoors, this time running through plays in a large hall instead of the main arena, where the ice floor was laid down.

The losing streak had dulled the public’s enthusiasm for the Packers in Milwaukee. A month earlier, they had brought a 3–0 record into a game against the Rams and drawn more than thirty-six thousand fans. Now, just twenty-five thousand came to County Stadium to watch them play the reigning NFL champions in wintry weather more suited to mid-January than the game’s actual date, November 15.