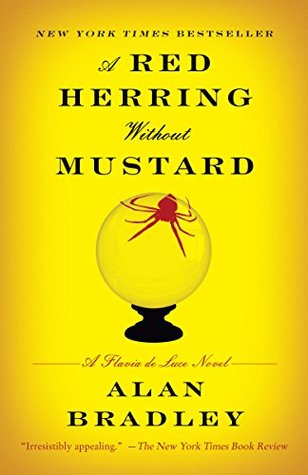

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alan Bradley

Read between

August 19 - August 26, 2020

remittance man,

If I were to be painted in oils, shellacked, and framed, I would be posed in my chemical laboratory and nowhere else. Hemmed in by beakers, bell jars, and Erlenmeyer flasks, I would be glancing up impatiently from my microscope in much the same way as my late great-uncle Tarquin de Luce is doing in his portrait, which still hangs in the picture gallery at Buckshaw. Like Uncle Tar, I would be visibly annoyed.

It was a Romany cob. I recognized it at once from photographs I had seen in Country Life. With its feathered feet and tail, and a long mane that overhung its face (from beneath which it peered coyly out like Veronica Lake), the cob looked like a cross between a Clydesdale and a unicorn.

What I wanted to do, actually, was to leap to my feet, strike a pose, and burst into one of those “Yo-ho for the open road!” songs they always play in the cinema musicals, but I stifled the urge and settled for a ghastly grin and an extra twiddle of the fingers. News of my abduction would soon be flying everywhere, like a bird loose in a cathedral. Villages were like that, and Bishop’s Lacey was no exception.

But when oxidation nibbles more slowly—more delicately, like a tortoise—at the world around us, without a flame, we call it rust and we sometimes scarcely notice as it goes about its business consuming everything from hairpins to whole civilizations. I have sometimes thought that if we could stop oxidation we could stop time,

We were given the distinct impression that she had personally conceived and executed the formation of that great river, with God standing helplessly on the sidelines, little more than a plumber’s assistant.

Mrs. M’s recent chin-wag at the kitchen door with the milk-float man was likely to have resulted in more swapping of intelligence than a chin-wag between Lord Haw-Haw and Mata Hari.

“I’m Flavia’s sister, Ophelia,” she was saying, extending a coral-encrusted wrist and a long white hand that made the Lady of Shalott’s fingers look like meathooks.

“I’ll ring for Mrs. Mullet,” Feely said, reaching for a velvet pull that hung near the mantelpiece, and which probably hadn’t been used since George the Third was foaming at the mouth. Mrs. M would have kidney failure when the bell in the kitchen went off right above her head.

Whenever I’m with other people, part of me shrinks a little. Only when I am alone can I fully enjoy my own company.

Tilda Mountjoy, whom I had met under rather unhappy circumstances a few months earlier. Miss Mountjoy was the retired Librarian-in-Chief of the Bishop’s Lacey Free Library where, it was said, even the books had lived in fear of her. Now, with nothing but time on her hands, she had become a freelance holy terror.

whatever the case, Brookie would be laid out on a wheeled trolley in Hinley by now, and someone—his next of kin—would have been asked to identify the body. As an attendant in a white coat lifted the corner of a sheet to reveal Brookie’s dead face, a woman would step forward. She would gasp, clap a handkerchief to her mouth, and quickly turn her head away. I knew how it was done: I’d seen it in the cinema.

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I was. At last we had something in common, Porcelain and I, even if it was no more than a mother who had died too young and left us to grow up on our own. How I longed to tell her about Harriet—but somehow I could not. The grief in the room belonged to Porcelain, and I realized, almost at once, that it would be selfish to rob her of it in any way.

“There was, of course, the tale in the Bhagavad Ghita of the princess who exuded a fishy odor …”

“There was a time when I loved to gaze down upon that ancient crook in the river as if from the summit of my years.

I dragged the rolling library ladder into position and began my climb: up, up, up—my footing more precarious with every step. Libraries of this design, I thought, ought to be equipped with oxygen bottles above a certain height, in case of altitude sickness.