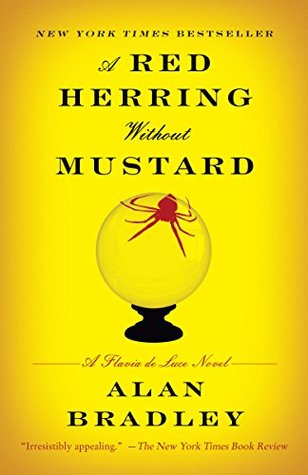

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alan Bradley

Read between

November 27 - November 29, 2019

I have sometimes thought that if we could stop oxidation we could stop time, and perhaps be able to—

I had already learned that sisterhood, like Loch Ness, has things that lurk unseen beneath the surface, but I think it was only now that I realized that of all the invisible strings that tied the three of us together, the dark ones were the strongest.

For weeks afterwards it was “Carl-this” and “Carl-that” with Feely prattling endlessly on about the muddy Mississippi, its length, its twists and bends, and how to spell it properly without making a fool of oneself. We were given the distinct impression that she had personally conceived and executed the formation of that great river, with God standing helplessly on the sidelines, little more than a plumber’s assistant.

Harriet’s ancient Rolls-Royce—a Phantom II—was kept in the coach house as a sort of private chapel, a place that both Father and I went—though never at the same time, of course—whenever we wanted to escape what Father called “the vicissitudes of daily life.” What he meant, of course, was Daffy and Feely—and sometimes me.

ALONE AT LAST! Whenever I’m with other people, part of me shrinks a little. Only when I am alone can I fully enjoy my own company.

The very best people are like that. They don’t entangle you like flypaper.

But wasn’t Father going to remark upon my cuts and abrasions? Apparently not. And it was at that moment, I think, it began to dawn upon me—truly dawn upon me—that there were things that were never mentioned in polite company no matter what; that blue blood was heavier than red; that manners and appearances and the stiff upper lip were all of them more important, even, than life itself.

How I longed to tell her about Harriet—but somehow I could not. The grief in the room belonged to Porcelain, and I realized, almost at once, that it would be selfish to rob her of it in any way.

I had long ago discovered that when a word or formula refused to come to mind, the best thing for it was to think of something else: tigers, for instance, or oatmeal. Then, when the fugitive word was least expecting it, I would suddenly turn the full blaze of my attention back onto it, catching the culprit in the beam of my mental torch before it could sneak off again into the darkness. “Thought-stalking,” I called the technique, and I was proud of myself for having invented it.

How I adored this man! Here we were, the two of us, engaged in a mental game of chess in which both of us knew that one of us was cheating.

It always surprises me after a family row to find that the world outdoors has remained the same. While the passions and feelings that accumulate like noxious gases inside a house seem to condense and cling to the walls and ceilings like old smoke, the out-of-doors is different. The landscape seems incapable of accumulating human radiation. Perhaps the wind blows anger away.

Visible and invisible: the trick of being present and absent at the same time.

“Damn it all—dash it all, Flavia,” he would say, as he always did, and then would begin one of those silences between us that would last for several days until one of us forgot about my offense. “Being at loggerheads,” Daffy called it,

Thinking and prayer are much the same thing anyway, when you stop to think about it—if that makes any sense. Prayer goes up and thought comes down—or so it seems. As far as I can tell, that’s the only difference.

I had been angry before, but this was like something ripped from the pages of the Book of Revelation. Could it be some secret fault in the de Luce makeup that was manifesting itself in me for the first time? Until now, my fury had always been like those jolly Caribbean carnivals we had seen in the cinema travelogues—a noisy explosion of color and heat that wilted steadily as the day went on. But now it had suddenly become an icy coldness: a frigid wasteland in which I stood unapproachable. And it was in that instant, I think, that I began to understand my father.

“They seem nice, though, your sisters, really,” Porcelain remarked. “Ha!” I said. “Shows what little you know! I hate them!” “Hate them? I should have thought you’d love them.” “Of course I love them,” I said, throwing myself full length onto the bed. “That’s why I’m so good at hating them.”