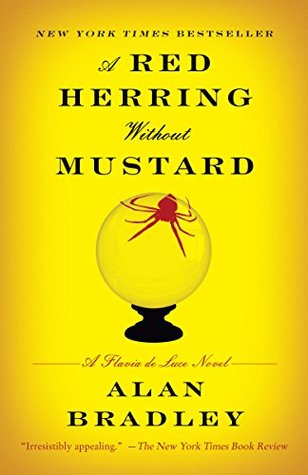

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alan Bradley

Read between

December 2, 2020 - January 4, 2021

When I come to write my autobiography, I must remember to record the fact that a chicken-wire fence can be scaled by a girl in bare feet, but only by one who is willing to suffer the tortures of the damned to satisfy her curiosity.

I set about cleaning up the shattered glass from the test tube she had dropped. “Here,” she said. “I should be doing that.” “It’s all right,” I told her. “I’m used to it.” It was one of those made-up excuses that I generally despise, but how could I tell her the truth: that I was unwilling to share with anyone the picking up of the pieces. Was this a fleeting glimpse of being a woman? I wondered. I hoped it was … and also that it was not.

“Until last year,” he said, watching the smoke vanish into the rain, “I was still able to make my way to the top of the Jack o’Lantern. For a young man in tip-top physical condition, it is no more than a pleasant stroll, but for a fossil in a wheelchair, it is torture. “But then, to an old man, even torture can be a welcome relief to boredom, so I often made the ascent out of nothing more than spite.

But I was hardly listening. Porcelain had lied to me. The witch! There’s nothing that a liar hates more than finding that another liar has lied to them.

“We always want to love the recipients of our charity,” the doctor said, negotiating a sharp bend in the road with a surprising demonstration of steering skill, “but it is not necessary. Indeed, it is sometimes not possible.”

Thinking and prayer are much the same thing anyway, when you stop to think about it—if that makes any sense. Prayer goes up and thought comes down—or so it seems. As far as I can tell, that’s the only difference.