More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

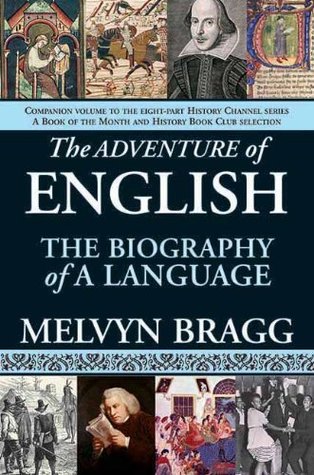

by

Melvyn Bragg

Read between

February 5, 2018 - January 17, 2019

there is, in this country, a tradition, across many disciplines, of the permitted amateur — doctors who were biologists and ornithologists, landed gentlemen who were scientists, zoologists and historians, clergymen who were encyclopaedic — and I hope I will be admitted to the ranks of those amateurs.

That is one powerful image — English arriving on the scene like a fury from hell, brought to the soft shores of an abandoned imperial outpost by fearless pagan fighting men, riding along the whale’s way on their wave-steeds. It is an image of the spread of English which has been matched by reality many times, often savagely, across one and a half millennia. This dramatic colonisation became over time one of its chief characteristics.

It would take two to three hundred years for English to become more than first among equals. From the beginning English was battlehardened in strategies of survival and takeover. After the first tribes arrived it was not certain which dialect if any would become dominant. Out of the confusion of a land, the majority of whose speakers for most of that time spoke Celtic, garnished in some cases by leftover Latin, where tribal independence and regional control were ferociously guarded, English took time to emerge as the common tongue. There had been luck, but also cunning and the beginnings of

...more

Somewhere, then, out on the plains of India more than four thousand years ago, began the movement of a language which was to become English. It was to drive west, to the edge of the mainland of Eurasia, west across to England, west again to America, and west across the Pacific where it met with Britain’s eastern trade across Asia and into the Far East and so circled the globe.

Despite being spoken by an overwhelming majority of the population, and despite preceding the Germanic invasion and creating an admired civilisation, the Celtic language left little mark on English. It has been calculated that no more than two dozen words were recruited to the conquering tongue. These are often words describing particular landscape features. In the mountainous Lake District of England where I live, for instance, there is still “tor” and “pen,” meaning hill or hill-top, as in village and town names such as Torpenhow and Penrith; there’s “crag” as in Friar’s Crag in Keswick,

...more

English had also dug into family, friendship, land, loyalty, war, numbers, pleasure, celebration, animals, the bread of life, the salt of the earth. This deep, long-toughened tongue proved to be the basis for dizzying monuments of learning and literature, for surreal jokes and songs superb and slushy. With the 20/20 vision of hindsight it seems as if English knew exactly what it was doing: building slowly but building to last, testing itself among competing tribes as in centuries to come it would be tested among competing nations, getting ready for as difficult a fight as was needed, branding

...more

This Northumbrian version is from an eighth-century manuscript. But it is not his words alone which are of central importance here. What matters, I think, is that through the words comes a faith new to most of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, the melders of English, and the ideas inside that faith. Ideas of resurrection, of a life after death, were in parts of the Germanic culture, but heaven and hell were of a different order. As was the idea of saints, the company of angels, of sin, and especially of a gentle Saviour, a non-warrior God; so were all the intellectual complexities of the Roman

...more

Runes could not only be used for poetry, they were sufficiently developed to have coped with War and Peace. But these straight lines were designed to be cut, chiselled on hard surfaces: wood, metal, stone and bone. The Christians brought with them the manuscript book and a different script, a technology more suitable for the new medium of vellum and parchment. English was emerging from the tribal Babel as a resourceful tongue, but it had no great written language and without that it would be for ever condemned to the limbo of vernaculars all over the world whose attempt to live on by sound

...more

to lose any language is to lose a unique way of knowing life.

Only writing preserves a language. Writing gives posterity the keys it needs. It can cross all boundaries. A written language brings precision, forces ideas into steady shapes, secures against loss. Once the words are on the page they are there to be challenged and embellished by those who come across them later. Writing begins as the secondary arm but s...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Written words stimulate the imagination as much as any other external reality — fire, storm, thunder — and yet they can express an internal reality — hope, philosophy, mood — in ways which also provoke the imagination, engage with that astounding faculty and set it off to make more words, adding to the visible map of the mind. Writing helps us fully to see what it is to be more completely human. “The word was made flesh and ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Between the Lord’s Prayer, laws of the land, and Beowulf, English had already sunk deep shafts into written language. Latin and Greek had created great bodies of literature in the classical past. In the East at about this time, Arabic and Chinese were being used as the languages of poetry. But at that time, no other language in the Christian world could match the achievements of the Beowulf poet and his anonymous contemporaries inside and outside the Church. Old English had found its home. It had fought its way to pre-eminence in a new, rich and diverse country. The adventure was under way.

English’s vital combination of deep obstinacy and, when faced with real extinction, astonishing flexibility and that vital survival technique, the power to absorb.

Alfred’s use of the English language united them. He was the first but by no means the last to see that loyalty and strength could come through an appeal to a shared language. He saw that inside the language itself, in the words of the day, there lay a community of history and continuity which could be invoked. He set out to teach the English English and make them proud of it, gather around it, be prepared to fight for it.

he drew a line diagonally across the country from the Thames to the old Roman road of Watling Street. The land to the north and east would be known as the Danelaw and would be under Danish rule. The land to the south and west would be under West Saxon, becoming the core of the new England. This was no cosmetic exercise. No one was allowed to cross the line, save for one purpose — trade. This act of commercial realism would more radically change the structure of the English language than anything before or since. Trade refined the language and made it more flexible.

Nevertheless the Vikings — Danes and Norwegians — brought words which enriched the language greatly. In northern parts of England the new invaders’ words predominate much more than in the south, exposing the north–south divide; and the accents too, from what linguists tell us — the Yorkshire, the Northumbrian, the Geordie, the Cumbrian — reach back to the sounds of the men in those longships

The number of their words which entered into general use was not as many as the strength of the invasion might have promised. But as it were to compensate for that, many of them have become keywords. For instance, “they,” “their” and “them” slowly replaced earlier forms (though they did not enter the language of London until the fifteenth century). Early loan words include “score,” and “steersman” is modelled on an Old Norse word, but they could also spread into the common tongue with “get” and “both” and “same,” “gap,” “take,” “want,” “weak” and “dirt.” What is impressive is its ordinariness.

...more

Although they most likely began their life in the common language pointing to the same thing or the same condition, they held a slightly different meaning which was used, as time went on, to make finer distinctions. This twinning, which later split and went rather different ways, became one of the most fertile and inventive characteristics of English. We can see it clearly at work in a modest but enduring number of word-pairings, here in pre-Norman times.

When English came into contact with the not wholly dissimilar Danish language, a lot of the inflected endings began to lose their distinctive nature. The new grammatical meld tended to happen in the borderland market towns; words followed the trade. Clarity for commerce may have been the chief driving force.

Word endings fell away. Prepositions came in which took the language away from the Germanic and made it more English. Instead of adding a lump on the end of words, you could use “to” or “with.” “I gave the dog to my daughter.” “I cut the meat with my knife.” The order of words became important and prepositions became more common as signposts around sentences.

Hybrid county dialects like these, which used to be spoken by the majority in a Britain of proud geographical minorities, are now disappearing as we move to cities and as the way of life which informed the way of speech falls away. It is impressive to see the efforts being made by dialect societies and local publishers to keep the tongue alive, to keep in touch, through the history in speech, with that period when we were stitching together languages old and new. But until very recently we still sounded not unlike those who had brought them from the western European shorelands more than a

...more

Alfred the Great had made the English language the jewel in his crown. His Wessex dialect would become the first Standard English.

The poem describing the Battle of Maldon is in Old English, full of the fury of alliteration, worked with words wisely woven.

Harold’s risky strategy, hurling all his best men into the front line in a make-or-break battle following a hurried march from the Battle of Stamford Bridge, deprived the land of English earls and chieftains, the very leaders and organisers who could have regrouped to fight another day against an opponent whose lines of communication were unreliable.

But the Normans came with an alien tongue and they imposed it. On Christmas Day 1066, William was crowned in Westminster Abbey. The service was conducted in English and Latin. William spoke French throughout. It is said that he attempted to learn English but gave up. French ruled. And the French language of rule, of power, of authority, of superiority, buried the English language.

Domesday was a good word for it. Twenty years after the Battle of Hastings, William sent out his officers to take stock of his kingdom. The monks of Peterborough were still recording the events of history in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and they noted, disapprovingly, that not one piece of land escaped the survey, “not even an ox or a cow or a pig.” William claimed all.

If you believe that words carry history and meaning often deeper than their daily purpose, then we see with the coming of the Normans an almighty shift of power. The words that regulated society and enforced the hierarchy, the words that made the laws, the words in which society engaged and enjoyed itself, were, at the top, and pressing down relentlessly, Norman French. Latin stood firm for sacred and high secular purposes. English was a poor third in its own country.

History was no longer with the Anglo-Saxons: and their language was of no consequence to those who saw the past in their own image. One way to destroy a personality is to cut out memory: one way to destroy a state is to cut out its history. Especially when that history comes out of the native language. Status is gone; continuity is disconnected; all that went into the making of the people the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles had recorded so carefully was of no account. The written language which bound it together guttered out.

The vocabulary of “romance” and “chivalry” brought the biggest culture shock to England since Alfred set out to re-educate the people: but where Alfred did this for God and for unity, the court of Henry and Eleanor did it for culture and pleasure. Eleanor was considered the most cultured woman in Europe. She attempted to change the sensibility of this doom-struck, crushed, occupied outpost of an island and it was she more than anyone else who patronised poets and troubadours whose verses and songs created the Romantic image of the Middle Ages as the Age of Chivalry — a glorious vision, little,

...more

I was in a summery valley, in a very secluded corner. I heard an owl and a nightingale holding a great debate. The argument was stubborn and violent and strong, sometimes quiet and sometimes loud. Ich was in one sumere dale In one suþe digele hale Iherde Ich holde grete tale An hule and one nihtingale at plait was stif an starc an strong Sumwile softe an lud among

Each one of those words could nourish two or three paragraphs on what was brought to England through the word. A word like “virtue,” for instance, part of the theme of chivalry now woven into the thinking, brought a secular sense of moral attainment into a land where the Church had provided all the words and thoughts for any elevated morality. The word then took off and metamorphosed into several other meanings: it allied itself with honour and with courage, for example, embellishing both; it became a boast, it became a weakness to be satirised; from rare and aristocratic it became common and

...more

It is important to emphasise that London was tiny by modern-day comparisons — a population of about forty thousand. Grandeur and the gutter were twinned in confined, crowded, sometimes dangerously infected places in which you did not risk drinking the water. A page at court would most likely be sent on messages and little missions all over the city and be able to savour all the variety of life on offer, life then being much lived on the streets. Dickens, the great fictional cartographer of London, is prefigured in Chaucer and both were steeped in the place.

It is a life which covered much of the important waterfront of the time and that knowingness, that lived experience, is one of the factors which gives The Canterbury Tales its historical strength.

Here Chaucer has inherited and appropriated the language and the ideas brought over by Eleanor of Aquitaine and in doing so he has created a figure who would feature in English history and in English literature deep into the twentieth century. He may be lurking yet: the man of quality and privilege who was also a man of integrity, modest and courteous especially to women, a man prepared to fight for a cause that was good but not brutalised by war, a gentle man. The element of irony is there: this roll-call of battle honours can also be described as a catalogue of massacres. Yet, idealised,

...more

Perhaps part of the appeal is what we might call the canny cross-class cluster. Not only from different parts of England but from different strata of society they come, joined in a common purpose, and whipped into line by the landlord, Harry Bailey. They take their turn to tell their stories. This gallery rises above feudalism, it presents a society of people happy to deal on equal terms before God and in story-telling. It has the deep attraction of a Golden Age and gives off the warm feeling that these were people who had come through a long tunnel and wanted to go together towards a new

...more

What Chaucer did most brilliantly was to choose and tailor his language to suit every story and its teller. The creation of mood and tone and the realisation of characters through the language they use is something we expect of writers today, so it is difficult to realise how extraordinary it was when Chaucer did it. He proved that the re-formed English was fit for great literature.

French words dominate here — “governaunce,” “plesaunce,” “paramours.” “Governaunce” and “plesaunce” are quite new, first recorded around the middle of the fourteenth century. Chaucer liked French borrowings and enjoyed introducing his own synonyms. English had the noun “hard”: Chaucer introduced the French (from Latin) “difficulte.” He gave us “disadventure” for “unhap,” “dishoneste” for “shendship,” “edifice” for “building,” “ignoraunt” for “uncunning.” Chaucer’s reputation in France was high in his own lifetime and looting the old conqueror’s language was fair game. He was unself-conscious

...more

The whole emphasis was on the mystery of it, the priests like a secret society, the Latin words so awesome in their ancient verity that, although some phrases would have stuck over the years, the whole intention was to impress and to subdue and not to enlighten. There was of course no English Hymnal, and no Book of Common Prayer. You were at the mercy of the priests. Only they were allowed to read the word of God and they did even that silently. A bell was rung to let the congregation know when the priest had reached the important bits. The priest stood not as a guide to the Bible but as its

...more

The prime mover in the fourteenth century was a scholar, John Wycliffe, probably born near Richmond in Yorkshire, admitted to Merton College, Oxford, when he was seventeen, charismatic, we are told, and a fluent Latinist. He was a major philosopher and theologian who believed passionately that his knowledge should be shared by everyone. From within the sanctioned, clerical, deeply traditionalist honeyed walls of Oxford, Wycliffe the scholar launched a furious attack on the power and wealth of the Church, an attack which prefigured that of Martin Luther more than a hundred years later.

New words are new worlds. You call them up and if they are strong enough, they keep in step with change and along the way describe more and more, provide new insights, evolve on the tongue and on the page. How many nuances and therefore meanings attach to the multiple uses of the world “humanity”? In the cause of bringing his greatly revered faith to the English, Wycliffe not only widened the ecclesiastical vocabulary — “graven,” “Philistine,” “schism” — he also let loose words which over the next four centuries would net meanings far removed from the perilously translated texts of medieval

...more

For reasons sincere and cynical, Latin was held to be the language of the Holy Book and ever more must be kept inviolate. Wycliffe had threatened the very voice of the Universal Church of the One Invisible God. It is a terrible example of the power in language. The Church was not finished with him yet. The Emperor Sigismund, King of Hungary, called together the Council of Constance in 1414. It was the most imposing council ever called by the Catholic Church. In 1415 Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and in the spring of 1428 it was commanded that his bones be exhumed and removed from

...more

The Avon to the Severn runs, The Severn to the sea. And Wycliffe’s dust shall spread abroad Wide as the waters be.

He was on the side of public opinion as anti-French fervour was once again at a high pitch. Victories over those who had conquered “us” and then become part of “us” carried a complicated sweetness. But when he returned from his campaigns, Henry Plantagenet continued to write in English.

Across the country a great number of dialects were spoken and people would still have had trouble understanding each other. The obstinacy of the English dialects is as impressive as the capacity of English to standardise, to absorb and to spread around the world. Almost one thousand years after the Anglo-Saxons had arrived with what was the fundament of the language, a man from Northumberland could still have the greatest difficulty in understanding a man from Kent. This local tenacity and loyalty continued for centuries and in certain areas it perseveres. It is like an ineradicable

...more

Chancery English, partly, it appears, because of the flow of people into London from the Midlands and the employment of a number of them as scribes, shows the influence of the Central and East Midlands dialects as well as that associated with London. So it could claim, when it emerges as the material of a literary language after about 1500, that it drew on a bigger reservoir than that of the metropolitan poets, even the author of The Canterbury Tales. London, with forty thousand people, was by far the biggest city in the country. But forty thousand people could be seriously affected by a

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

We’ll begin with a box and the plural is boxes. But the plural of ox should be oxen not oxes. Then one fowl is goose, but two are called geese. Yet the plural of mouse should never be meese. You may find a lone mouse or a whole lot of mice. But the plural of house is houses not hice. If the plural of man is always called men, Why shouldn’t the plural of pan be called pen? The cow in a plural may be cows or kine, But the plural of vow is vows and not vine. And I speak of foot and you show me your feet, But I give you a boot . . . would a pair be called beet?

This reflects the survival of old plural forms (ox, oxen), historical sound changes in Old English words (foot, feet), and loan words adopting “s” as a plural (vows). Broadly, there were reformers who wanted to spell words according to the way they were pronounced and traditionalists who wanted to spell them in one of the ways they always had been. There was another party, however. We could call them the Tamperers. In a desire to make the roots of the language more evident and perhaps give it more style, more class, some words that had entered English from French were later given a Latin look.

...more

The Tamperers were attempting in their way to bring reason to bear on the development of the language. English has never been very partial to reason and as if to prove it, at the same time as the “b”s and the silent “l”s and “h”s were being smuggled into perfectly sound words, the Great Vowel Shift occurred which resulted in many of the English pronouncing most things differently anyway. When properly read aloud, the fourteenth-century English of Chaucer sounds strange to modern ears in a way that, on the whole, the late sixteenth-century English of Shakespeare does not. For example, Chaucer’s

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In the years between Chaucer’s birth and Shakespeare’s death, English went through a process now known as the Great Vowel Shift. People in the Midlands and south of England changed the way they pronounced long vowels (long vowels are those that are held in the mouth for a comparatively l...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Printing had largely fixed spelling before the Great Vowel Shift got under way. So to a large extent our modern spelling represents a pre-GVS system, whereas the language as a result of the GVS had changed enormously. Spelling fixed: spoken in turbulence: result — out of sync.