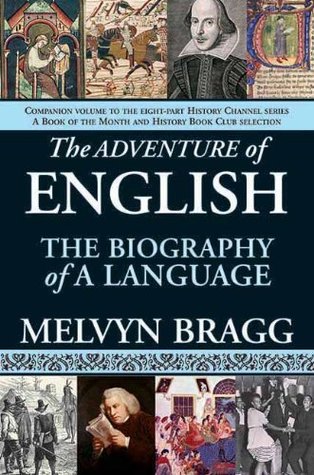

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Melvyn Bragg

Read between

February 5, 2018 - January 17, 2019

The King had set an example; Chancery followed; the printing press reinforced the importance of a common written language. By the end of the fifteenth century, English was the language of the state and equipped to carry messages of state in an increasingly uniform spelling north, south, east and west, its manuscripts and later its books rolling over the old dialects which nevertheless stayed stoutly on the tongue.

There was only one more kingdom for English to conquer. The keepers of this eternal kingdom, the Roman Catholic hierarchy, were being threatened by popular movements, like that of Wycliffe, all over Europe and their reaction was to dig in deeper and fight with all the natural and supernatural means they thought and were thought to have at their command. Latin was their armour, believed to be blessed and made invulnerable by God Himself. Any assault on the Latin Bible was an assault on the spirit, meaning and purpose of the Church.

It is not always easy fully to comprehend or even imagine what was at stake. It was a great power battle. The reach of the Roman Catholic Church across many countries, states, principalities and peoples was unique. It was wealthy and a sought-after ally in war. It demanded obedience through its monopoly of the one true faith. Its parish priests covered almost every acre of ground, heard confessions, had the power to absolve sins, enforced attendance at church, the paying of Church taxes and conformity with the Church’s rulings on all matters of public and of private morality; even sex was a

...more

William Tyndale left England to pursue his work outside the repressive spy-state set up by Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey. He would never return. He met Erasmus and later Luther, the two key men in the movement towards what became Protestantism. He settled in Cologne and began single-handedly to translate the New Testament not from Latin but from the original Greek and Hebrew. It was this, no doubt, coupled with Tyndale’s genius for language, which made his translations so telling and memorable.

Two years later, six thousand copies had been printed abroad — evidence of the substantial nature of the patronage Tyndale must have received from the wool merchants of Gloucestershire, and of the speed and efficiency of print. The new Bibles were packed and sent to the coast ready to be smuggled into England. Yet again English comes to England from across the sea, this time written English, some of the most sublime ever put on paper. But Henry VIII and Wolsey’s spies informed them of this invasion. It now seems quite extraordinary, but the whole country was put on alert. In order to prevent

...more

We use them still: “scapegoat,” “let there be light,” “the powers that be,” “my brother’s keeper,” “filthy lucre,” “fight the good fight,” “sick unto death,” “flowing with milk and honey,” “the apple of his eye,” “a man after his own heart,” “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak,” “signs of the times,” “ye of little faith,” “eat, drink and be merry,” “broken-hearted,” “clear-eyed.” And hundreds more: “fisherman,” “landlady,” “sea-shore,” “stumbling-block,” “taskmaster,” “two-edged,” “viper,” “zealous” and even “Jehovah” and “Passover” come into English through Tyndale. “Beautiful,” a

...more

Tyndale was not only bringing the word of God to the people, he was also, within that process, bringing in words which carried ideas, described feelings, gave voice to emotions, expanded the way in which we could describe how we lived. Words which tell us about the inner nature of our condition; words which, as in the beatitudes, express as never before or since the great loving dream of a moral life which applies to everyone and challenges every ruling description of society from the beginning until today. Writer after writer, in the UK, in the USA, in Australia, on the Indian subcontinent,

...more

In his last letter, Tyndale asked that he might have “a warmer cap, for I suffer greatly from the cold . . . a warmer coat also for what I have is very thin; a piece of cloth with which to patch my leggings. And I ask to have a lamp in the evening, for it is wearisome to sit alone in the dark. But most of all I beg and beseech your clemency that the commissary will kindly permit me to have my Hebrew Bible, grammar and dictionary, that I may continue with my work.” And continue, for a short while, he did, bringing us phrases, poignantly, heart-breakingly, like “a prophet has no honour in his

...more

It was unconditional surrender. It was defecting en masse to the side of the enemy. It was purging the past out of memory. It was now the King’s Bible’s English. Where the medieval Catholic Church and Henry VIII most violently up into the 1530s had kept the Bible from the people, Henry’s new Church set out to get the Bible to as many as possible. It has had an incalculable influence on the spread of our language. For centuries it was heard week in week out, sometimes day in day out, by almost all English-speaking Christians wherever they were, and its precepts, its images, its proverbs, its

...more

The fifty-four translators made very little attempt to update his language, which was now eighty years old. Even though by 1611, English had undergone further revolution, the King James translators would still use “ye” sometimes for “you,” as in “ye cannot serve God and Mammon,” even though very few said “ye” in common speech any more. They used “thou” for “you,” “gat” for “got,” “spake” for “spoke” and so on. Either they were too struck by the beauty and power of Tyndale’s prose to want to interfere with it, or this was a deliberate act of policy. They may have chosen to keep archaic forms.

...more

After 1588, the naval effectiveness of the comparatively small island grew even stronger and opened up the world to trade. This brought a massive injection into the language. As England imported a huge cargo of goods, English imported a huge cargo of vocabulary. Another ten to twelve thousand new words entered English in this Elizabethan and Jacobean period and delivered a new map of the world and new ideas.

At the time of the Spanish Armada, England was well behind other European powers in the reach of its colonial conquests and English inevitably lagged badly in the influence it exerted abroad. Portuguese had already made its mark in Brazil and was biting deeply into southern America; Spanish had been spoken in Cuba and Mexico for more than half a century and Spain was taking its trade, its religion and its culture and its language all around the New World. Over eight hundred years earlier, Arabic had raced through the Middle East and North Africa and could still be called an imperial language,

...more

Yet the biggest and most important seam of all at that time was mined in England itself, chiefly in Oxford and Cambridge. It is another twist in the adventure of English that the heirs of those classical scholars whose learning and courage had pushed through the translation of the Bible from Latin into English and toppled Latin’s supremacy for ever now led the movement to revive the study of Latin. It was, I think, this growing addiction to uncover new words which was the driving force in this revival.

Renaissance scholars at the two universities founded schools teaching pure and literary Latin. Roger Ascham, Elizabeth I’s tutor, was just one of those Renaissance scholars. Classical texts written by Seneca, Lucan and Ovid, for example, were sourced from the medieval manuscripts into which they had been copied and translated into English. The scholars, or humanists as they came to be known, saw Latin as the language of classical thought, science and philosophy, all of which were gathering interest as the Renaissance rolled through the minds of Europe. It was also the universal language, with

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

A closer look at the words borrowed from Latin and Greek in the developing area of medicine gives us a snapshot of the time. So successful was the classical branding of medical terms during the Renaissance that it has gone on ever since. Among the hundreds of words that arrived from Greek via Latin were our “skeleton,” “tendon,” “larynx,” “glottis” and “pancreas.” From Latin we also inherit “tibia,” “sinuses,” “temperature” and “viruses” as well as “delirium” and “epilepsy.” Our “parasites” and “pneumonia,” even our “thermometers,” “tonics” and “capsules,” are all words of classical origin. We

...more

Every day in the sixteenth century we spoke Latin, Greek, French — Norman, Francien and Parisian — Dutch, Anglo-Saxon and Norse and sprinklings of languages from Celtic to Hindi, all alchemised into English. And it has multiplied greatly since then.

The word-grab into Greek and Latin for the new science and medicine of the Renaissance might have had elements of apprehension and snobbery about it. Respectability is often craved by the new kid on the block and the classical languages certainly helped. Reassurance is often another necessity when coming in out of the blue, and what could be more reassuring than languages with thousands of years of achievement? Great and lasting empires had been built, learning had flourished, laws been laid down in Greek and Latin. There was also, perhaps, a little snobbery, which grew as time went on. To

...more

The Inkhorn Controversy is interesting because it set up a discussion which still goes on as to the most effective, the most poetic, the most honest, even the “truest” way of writing English. The leading opponent of the increasing invasion of Latin and Greek words was Sir John Cheke (1514–57), Provost of King’s College, Cambridge. He argued strongly that English should not be polluted by other tongues. Ironically, Cheke was a classicist and the first Regius Professor of Greek in Cambridge. Nevertheless, Cheke believed that English should be reappraised as a Germanic language. It had to go

...more

It is significant that, as Francis Bacon was to do in the time of Shakespeare, Cheke should seek out the analogy with money, with the wealth of man, with the financial stability of the state. Words, like money, must be kept in credit, no National Debt, balanced books. Yet the words Cheke used — like “bankrupt” and even “pure” itself — are not of Anglo-Saxon or Germanic origin. They are from the Latin-based languages, Italian and French. He disliked what he called “counterfeit” words — though “counterfeit” itself was not of Anglo-Saxon origin.

New formations came in from prefixes: “disabuse,” “disrobe,” “nonsense,” “uncivilized”; from suffixes: “gloomy,” “immaturity,” “laughable”; from compounding: “pincushion,” “pine-cone,” “rosewood”; and conversions from verb to noun as in “invite” and “scratch” and from noun to verb as in “gossip” and “season.” Confidence could be seen everywhere.

England had to wait until the dawn of the seventeenth century, 1604, to get its own dictionary. This represents the first indication of a challenge to the rest of Europe, as it was eight years ahead of the first Italian dictionary, and thirty-five years before the French. Although, to put it in a rather longer perspective, it was eight hundred years after the first Arabic dictionary and nearly a thousand years after the first Sanskrit dictionary in India.

Cawdrey intended his dictionary to be used by those who might not understand words “which they shall heare or read in Scriptures, Sermons or elsewhere.” This was not a book for scholars. It was a book for the gentlefolk and for intellectually ambitious people to catalogue new words and to explain the new ideas connected with those words. The English population was growing, and growing more educated. One estimate is that by 1600, half of the three and a half million population — at least in towns and cities — had some minimal education in reading and writing. Their minds were hungry, wanting to

...more

By the middle of the sixteenth century, French had already had the poems and works of Villon, Du Bellay and Ronsard to rival or at least challenge those of Petrarch. Italian’s earlier literary Renaissance had also produced Dante, Machiavelli and Ariosto, while Spanish could boast Juan del Encina and Fernando de Rojas. Although English could already claim Chaucer and his contemporaries, their works were written in an English which had become to a great extent defunct. Because of changes in pronunciation and in forms of speech — like the loss of the final “e” — the Tudors could not hear

...more

To write in your own language, to play with it and mould it — these all became aims to which the educated wished to aspire. English literature became the vogue. Roger Ascham, Elizabeth I’s tutor, said that his colleagues would much rather read Malory’s mid-fifteenth-century tale Le Morte d’Arthur (in English) than the Bible. They began to copy and experiment. Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, beheaded by Henry VIII, had used blank verse when translating Virgil’s Aeneid.

One of Surrey’s fellow poets, the humanist and courtier Sir Thomas Wyatt, was acquitted of treason and escaped Henry VIII’s execution machine, then travelled to Italy, France and Spain. In the French and Italian courts he found a form that would shape and fit English for its unparalleled poetic future: the sonnet. The sonnet was a fourteen-line poem written in iambic pentameters which had been in use since the thirteenth century. Wyatt — like so many others — looked towards the great Italian Petrarch’s sonnets and noted also the love motifs which inhabited so many of them, for which indeed

...more

It might seem hard to argue that the English sonnet that developed from Wyatt’s raid on Europe was crucial to the development of the English language. But many do. The English language by now was a thickly plaited rope, a rope of many strands, still wrapped around the Old English centre, still embellished with Norse, lushly fattened and lustred with French, and it was now a language serving many demands. It was a language for religion, a language for law, a language for the court, a language for the fields, a language for war, for work, for celebration, for rage, for rudery and puritanical

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Queen Elizabeth I has a fair claim to be the best educated monarch ever to sit on the throne of England. Apart from her mastery of rhetoric — demonstrated at Tilbury — she spoke six languages and translated French and Latin texts. Furthermore, she enjoyed writing poetry: I grieve and dare not show my Discontent; I love and yet am forc’d to seem to hate; I do, yet dare not say I ever meant; I seem stark mute but Inwardly do prate.

Sidney had set a daunting example in his life. The intensity and high-flying drama of the life seemed somehow a springboard for his writing. There are two thousand two hundred twenty-five quotations from Sidney in the Oxford English Dictionary. Numerous first usages are attributed to Philip Sidney: “bugbear,” “dumb-stricken,” “miniature” for a small picture. He was fond of adding words together to form evocative images ranging from “far-fetched” to “milk-white” horses, “eypleasing” flowers, “well-shading” trees, to more unusual ones like “hony flowing” eloquence, “hangworthy” necks and

...more

Partly because of Sidney, poetry, not royal commands or sermons or even the Bible itself, poetry became the benchmark for English. By the 1600s, poets like John Donne, Thomas Campion, Michael Drayton, Ben Jonson, George Herbert and many more were writing lines such as Jonson’s “Drinke to me, onely, with thine eyes” and Donne’s “No man is an Iland” which have become everyday expressions. And in enriching their writing technique, poets also enriched English as a language, fit for the most testing poetic and dramatic endeavours. After his death on the battlefield, Sir Philip Sidney, the young man

...more

The struggle for the “right and proper” ways to speak was and is a continuing debate. Sir Walter Raleigh’s Devonshire accent was strongly remarked on. Local accent was a matter of comment for a long time. Wordsworth’s Cumbrian accent was noted at the end of the eighteenth century; D. H. Lawrence’s Nottinghamshire (and his dialect in poems and short stories) at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries; William Faulkner’s southern American in the mid twentieth; Toni Morrison in the late twentieth century. But on the whole these were exceptions: the standard was

...more

The Renaissance saw the beginning of the great writing rift, the splitting away of literature from everyday speech. Dialect words and terms often made an appearance in the work of major mainstream writers — Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy, for instance — but dialect writing was and is still, largely, thought to be below the salt. On the whole, literature still belongs to the high table, as George Puttenham indicated in 1589, and realists of the sixteenth century saw this and identified it. Writing had its own web to spin, its own written rhythms to discover, its own silent world

...more

stages became a public crucible of English and the playwrights of the period transformed the turbulent mixed and still unsettled English language that they were reading and hearing. They combined the rich vocabulary and poetry and charmed voices of the courtiers with the slang and sensation and vulgar quick-fire action of the commoners. Because the theatres of the time had no scenery and barely any props, language was the means of choice on the stage to captivate the audience. The scene was set for Shakespeare.

The plays that were written by Shakespeare as well as those by his contemporaries, Marlowe, Jonson, Marston and Chapman, and later Webster and Middleton, attracted a truly incalculable proportion of the population of London. The Globe could hold between three thousand and three thousand five hundred people — and there were five other theatres in London which could rival the Globe. A ten-day run for a play counted as a long run and the London population of merely two hundred thousand inhabitants demanded constant novelty, especially as theatre-going became such a craze that most of those who

...more

In the eighteenth century, Dr. Johnson took a calmer perspective and a broader sweep: From the authors which rose in the time of Elizabeth [he wrote], a speech might be found adequate to all purposes of use and elegance. If the language of theology were extracted from Hooker and the translation of the Bible; the terms of natural knowledge from Bacon; the phrases of policy, war and navigation from Raleigh; the dialect of poetry and fiction from Spenser and Sidney; and the diction of common life from Shakespeare, few ideas would be lost to mankind for want of English words in which they might be

...more

Almost every word could be used as almost any part of speech. There were no rules and Shakespeare’s English ran riot. If the stature of a writer depends on his quotability then Shakespeare appears to be unmatchable. “To be or not to be, that is the question” is known around the world. It is probably the best known quotation in any language ever.

as has been mentioned, words can stand for ideas. Words are both an expression of and a report on the human condition. Shakespeare abundantly exemplifies and demonstrates this. In Hamlet, for example, one phrase “to thine own self be true” began to explore the notion of personal identity, the study of which has intensified since his day to an extent that even he might not have been able to predict. The great soliloquies express dynamic shifts in states of mind. Drama can be internal. He is saying no less than — this is how we think and how we think is itself dramatically rich. In Greek drama,

...more

Perhaps scholars can track to their Bible source some of the expressions and attitudes in Shakespeare. For a youth so evidently sensitive to language, it must have been influential. Especially as, newly liberated into English, the words might have been read with passion and freshness and authority. It was prepared as a preacher’s Bible — well as of truth. This was a language to reckon with. It could be that this unacknowledged education was as important as anything learned on the hard school bench. In Holy Trinity Church in Stratford, it is good to think that in some measure Tyndale was

...more

Lacking the university education that mattered a lot to the dedicated poets of fashion, Shakespeare had to be outstandingly responsive to poetry and to fashion, and he was. It appears that he was well aware of the Inkhorn Controversy and, as usual, he waded in. He used new words which had appeared from the middle to the end of the sixteenth century, like “multitudinous,” “emulate,” “demonstrate,” “dislocate,” “initiate,” “meditate” and “allurement,” “eventful,” “horrid,” “modest” and “vast.” He invented and was also very fond of composite words: “canker-sorrow,” “widow-comfort,” “bare-pick’t,”

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Shakespeare’s accent would have sounded rather like some current regional accents as used today by older speakers — unsurprising given the stubborn grip of the dialects of England which retain pronunciations older than those in “educated” English. He would have used a rolled “r” in words like “turn” and “heard.” “Right” and “time” would be “roight” and “toime.” Alert as any, though, to the passages l...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Shakespeare rhymed “tea” with tay, “sea” with say, and “never die” with memory. “Complete” has the stress on the first syllable in Troilus and Cressida: “thousand com-plete courses of the Sun,” but on the second in Timon of Athens: “Never com-plete.” “An-tique,” “con-venient,” “dis-tinct,” “en-tire,” and “ex-treme” would all have the stress on the first syllable. “Ex-pert,” “para-mount,” and “par-ent,” on the last. There was a great deal of what might be termed “poetic licence.”

John Barton made a stunningly simple point about Shakespeare’s language: It’s the monosyllables that are the bedrock and life of the language. And I believe that is so with Shakespeare. The high words, the high phrases he sets up to then bring them down to the simple ones which explain them. Like “making the multitudinous seas incarnadine, making the green one red.” First there is the high language, then the specific clear definition. At the heart of Shakespeare, listening to it for acting, the great lines, often the most poetic, are the monosyllables. Deep feeling probably comes out in

...more

Is it pushing this to point out that the monosyllables are or are nearest to Old English? That the deepest, most earthed of the languages in our many-layered tongue carry the deepest, most basic meanings? It is as if the foreign elaborations, the wonderful artifice of the new and the inserted words only really strike fire when they hit the flint of the old. Since Shakespeare’s time, one way to divide writers is between the embellished, the high extravagant stylists — Charles Dickens, James Joyce — and the more earthed — George Eliot, Samuel Beckett. Of course there was crossover in these as in

...more

It is his contemporary Ben Jonson who caught him best. Writing a few years after Shakespeare’s death, he used terms which might have been thought hyperbolic and now seem prophetically accurate. It was 1623, the year in which Shakespeare’s First Folio was published. Thou art a monument without a tomb And art alive still while thy book doth live And we have wits to read and praise to give. Jonson ranks his contemporaries well below him; even the Greeks, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles, are called on to honour him. Jonson takes great pride in Shakespeare’s nationality. Since the joining of

...more

English went west once more on its most fateful journey since the fifth century. A weighty proportion of the early settlers came from East Anglia, the land of the Angles where Englalond became England. The Mayflower families and those who followed them were, on the whole, people of above-average literacy, moral certainty, religious passion and, possibly, among the most stout-hearted. It was the first mass exodus from a very small country — about three and a half million (a fifth of the population of France at that time) — and the beginning of centuries of considerable emigration, of seeding of

...more

William Bradford caught the moment. “Whilst we were busied hereabout, we were interrupted, for there presented himself a savage which caused an alarm. He very boldly came all alone and along the houses straight to the rendezvous, where we intercepted him, not suffering him to go in, as undoubtedly he would, out of his boldness. He saluted us in English and bade us ‘welcome.’ ” What odds against the first word the Pilgrim Fathers met with in America, and from a “wild man,” being “welcome”? That having travelled three thousand miles and hit a spot on the continent they had not aimed for, they

...more

Squanto had been kidnapped by English sailors fifteen years before and taken to London, where he was trained to be a guide and interpreter and learned English. He managed to escape on a returning boat. By chance, or through God’s providence, the Pilgrims had hit America next to the tribal home of the Native American who was certainly the only fluent native-English speaker for hundreds of miles around and arguably the most fluent English speaker on the entire continent: and he had been delivered into their hands, or they into his.

Perhaps it was fear of the unknown which made them reach for the comfort of old familiar names. They certainly did this with place names. Ipswich, Norwich, Boston, Hull, several Londons, Cambridge, Bedford, Falmouth, Plymouth, Dartmouth — there are hundreds in New England. New England, those two simple words, say a very great deal. Insofar as they could, these stern fathers wanted to recreate the place they had left behind, knowing full well it was new but wanting for many reasons to hold on to the old.

It seems that from quite early on there was an erosion of original regional accents. Being crammed into a single boat and forced into cramped intimacy might have speeded this up. The central and essential features of life were reading aloud from the Bible and listening to very long sermons. Rhetoric, the delight of Elizabeth I, was not encouraged. As the preface to the Bay Psalm Book, the first book published in English in America in 1640, said, “God’s altar needs not our polishings.” A standard accent began to appear reasonably quickly. These people were obsessively aware of the power of

...more

War brought other colonies under British rule. New Amsterdam was taken and became New York in 1664. New Sweden became New Delaware. Dutch terms remain in Breukelen (Brooklyn) and Haarlem, and in “waffle,” “coleslaw,” “landscape” (as it had done back in England), “caboose,” “sleigh,” “boss” (to become very important as a way in which slaves and servants could address their employers or owners without calling them “master”), “snoop” and “spook.” There was rivalry with the French of course. Why should that incessant enmity be given up just because they had moved thousands of miles west and to a

...more

American English was gathering its own forces although there are those who argue that its vocabulary does not become distinctively American until some decades after the Declaration of Independence. Before this, however, words appeared which are new to the English language and are found during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They derive their popularity from the development of the American political system: “congressional,” “presidential,” “gubernatorial,” “congressman,” “caucus,” “mass meeting,” “state-house,” “land office.” (Again, the English habit of looking to Latin to validate

...more