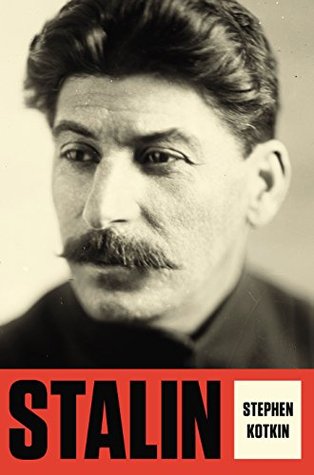

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 30 - April 25, 2022

But Stalin’s rule also reveals how, on extremely rare occasions, a single individual’s decisions can radically transform an entire country’s political and socioeconomic structures, with global repercussions.

This book is also based upon exhaustive study of scans as well as microfilms of archival material and published primary source documents, which for the Stalin era have proliferated almost beyond a single individual’s capacity to work through them.

Imperial Russia came to resemble a religious kaleidoscope with a plenitude of Orthodox churches, mosques, synagogues, Old Believer prayer houses, Catholic cathedrals, Armenian Apostolic churches, Buddhist temples, and shaman totems.

Stalin’s origins, in the Caucasus market and artisan town of Gori, were exceedingly modest—his father was a cobbler, his mother, a washerwoman and seamstress—but in 1894 he entered an Eastern Orthodox theological seminary in Tiflis, the grandest city of the Caucasus, where he studied to become a priest.

Stalin’s dictatorship, as we shall see, was a product of immense structural forces: the evolution of Russia’s autocratic political system; the Russian empire’s conquest of the Caucasus; the tsarist regime’s recourse to a secret police and entanglement in terrorism; the European castle-in-the-air project of socialism; the underground conspiratorial nature of Bolshevism (a mirror image of repressive tsarism); the failure of the Russian extreme right to coalesce into a fascism despite all the ingredients; global great-power rivalries, and a shattering world war.

More than for any other historical figure, even Gandhi or Churchill, a biography of Stalin, as we shall see, eventually comes to approximate a history of the world. • • •

WORLD HISTORY IS DRIVEN BY GEOPOLITICS. Among the great powers, the British empire, more than any other state, shaped the world in modern times.

Everyone knows that Karl Marx, the radical German journalist and philosopher, loomed over imperial Russia like over no other place. But for most of Stalin’s lifetime, it was another German—and a conservative—who loomed over the Russian empire: Otto von Bismarck.

Bismarck the statesman was one for the ages. He craftily upended his legions of opponents, both outside and inside the German principalities, and instigated three swift, decisive, yet limited wars to crush Denmark, then Austria, then France, but he kept the state of Austria-Hungary on the Danube for the sake of the balance of power. He created pretexts to attack when in a commanding position or baited the other countries into launching the wars after he had isolated them diplomatically.

Bismarck did not invoke virtue, but only power and interests. Later this style of rule would become known as realpolitik, a term coined by August von Rochau (1810-73), a German National Liberal disappointed in the failure to break through to a constitution in 1848.

Bismarck strategized to make himself indispensable partly by making everything as complex as possible, so that he alone knew how things worked (this became known as his combinations). He had so many balls up in the air at all times that he could never stop scrambling to prevent any from dropping, even as he was tossing up still more.

He remembered perceived slights, something of a cliche in the blood-feud Caucasus culture but also common among narcissists (another word for many a professional revolutionary).

His youthful years involved becoming a Marxist of Leninist persuasion and battling not just tsarism but the factions of other revolutionaries.32

That said, the Russian empire defied nearly every possible prerequisite: its continental climate was severe, and its huge open frontiers (borderless steppes, countourless forests) were expensive to defend or govern.3 Beyond that, much of the empire was situated extremely far to the north.