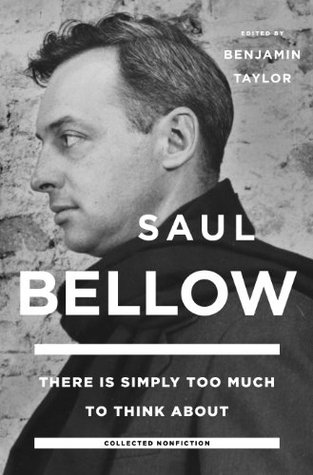

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The 1947 edition of the Illinois State Guide says that the flood of 1937, which rose six feet above the levee, “marked the end of Shawneetown’s pertinacious adhesion to the riverbank.” Reasonable people, the authors of the guide spoke prematurely. The pertinacious adhesion continues in spite of reason and floods.

“Well,” he said, “writers have always come out of the gutter. The gutter is their proper place.”

“He opened the door.” Did he, now? “She lit his cigarette.” So what? It is assumed that these declarations are important or will seem so. But why? Documentation, observation, details of action cannot by themselves give life, no matter how authentic or faithful to experience they may be. You can’t construct a tree with twigs. You cannot give importance to events by the authority of Experience, merely.

You may find illumination anywhere—in the gutter, in the college, in the corporation, in a submarine, in the library.

This contrast of a superior reality with daily fact is the peculiar field of the novel.

As the external social fact grows larger, more powerful and more tyrannical, man appears in the novel reduced in will, strength, freedom and scope—until, in Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, the hero is not even an antihero like Dostoyevsky’s, great by reason of his ressentiment, but merely a man of no importance, a ridiculous social creature. And if man is of no importance, how is the novel—how, for that matter, is any human activity—justified?

Flaubert’s aim was an aesthetic one: the creation of beauty as a reply to the punishment and pain of degraded existence.

In Tocqueville we read, “Nothing conceivable is so petty, so insipid, so crowded with paltry interests, in one word so anti-poetic, as the life of a man in the United States.”

The task of a novelist is still, as I see it, to attempt to fix a scale of importance and to rescue from styles, languages, forms, abstractions, as well as from the assault and distraction of manifold social facts, an original human value. I do not believe in a hierarchy of feelings descending in a line from aristocracy to mass civilization. Let the aristocratic dead bury their dead and the democratic dead their dead, too. I believe simply in feeling. In vividness. Where feeling is synthetic, ideals of greatness are merely dismal. Only feeling brings us to conceptions of superior reality.

We have for hundreds of years had an idolatry of the human image, in the lesser form of the self and in the greater form of the State. So when we think we are tired of Man, it is that image we are tired of. Man is forced to lead a secret life and it is into that life that the writer must go to find him. He must bring value, restore proportion; he must also give pleasure. If he does not do these things he remains sterile himself.

The most ordinary Yiddish conversation is full of the grandest historical, mythological and religious allusions. The Creation, the Fall, the Flood, Egypt, Alexander, Titus, Napoleon, the Rothschilds, the sages and the Laws may get into the discussion of an egg, a clothesline or a pair of pants. This manner of living on terms of familiarity with all times and all greatness contributed, because of the poverty and powerlessness of the Chosen, to the ghetto’s sense of the ridiculous.

He declines to suffer the penalties the world imposes on him.

the pitiful obstinacy of a “position,” that marvelous dishonesty of modern politics.

How many European novels today have the power of the factual accounts of deportations, camps, escapes, battles, hitherto unknown relations?

“good” writing of The New Yorker is such that one experiences a furious anxiety, in reading it, about errors and lapses from taste; finally what emerges is a terrible hunger for conformism and uniformity. The smoothness of the surface and its high polish must not be marred. One has a similar anxiety in reading Hemingway and comes to feel in the end that he wants to be praised for the offenses he does not commit.

Only to think is to feel one’s powerlessness and that is why Hemingway himself, and his heroes as well, are in extreme need of movement. They are resisting the passivity and impotence that result from the prevalence of thought.

“Cowardice,” Hemingway has written, “. . . is almost always simply a lack of ability to suspend the functioning of the imagination.”

There is a repetition-compulsion in Hemingway and he is the poet of the crippled state in which men survive the heavy blows of fortune, the mutilations of war, the cruelties of women. Wounded and broken, they somehow mend; the hero establishes an economy of imagination that frees his muscles, his senses and his spirit to accomplish this recovery.

Hemingway is forever trying to make his heroes virile and dominant. They are supposed to be cast in the right mold. They are exemplary;

It is plain that Hemingway thinks of himself as a representative man, one who has had the necessary and qualifying experiences. He has not been disintegrated by the fighting, the drinking, the wounds, the turbulence, the glamour. He has not gotten lost in the capitals of the world or disappeared in the huge continents. Nor has he been made anonymous with the oceanic human crowd. He keeps the outlines of his personality. This is why his characters are so dramatic: They offer the promise of a strong and victorious identity. But it is strange that Hemingway’s standards, unlike Whitman’s, should

...more

(It’s strange how Hemingway detests tourists—other tourists.

Society does not do much to help the American to come of age. It provides no effective form. That which churches or orders of chivalry or systems of education did in the past, individuals now try to do independently. When the boy becomes a man in an American story, we are asked to believe that his experience of the change was crucial and final; no further confirmation is necessary. There is one extraordinary exception in American fiction and that is in The Great Gatsby.

Where, then, is the right man? Fitzgerald does not pretend that he can produce him and the absence of a right man creates a certain slackness in the novel. The fact that money does not confer manhood seems to have shocked and scandalized Fitzgerald.

make their own synthesis out of the vast mass of phenomena, the seething, swarming body of appearances, facts and details. From this harassment and threatened dissolution by details, a writer tries to rescue what is important. Even when he is most bitter he makes by his tone a declaration of values and he says in effect: “There is something nevertheless that a man may hope to be.”

In a time of specialized intelligences, modern imaginative writers make the effort to maintain themselves as unspecialists and their quest is for a true middle-of-consciousness for everyone. What language is it that we can all speak and what is it that we can all recognize, burn at, weep over; what is the stature we can without exaggeration claim for ourselves; what is the main address of consciousness?

fine novels are few and far between.

the chains of today might become the laurels of tomorrow.

Love, duty, principle, thought, significance, everything is being sucked into a fatty and nerveless state of “well-being.”

statement by Goethe that a writer ought not to pick up his pen unless he intends his words to be read by at least a million readers. None but the crankiest authors would quarrel with this assertion. Naturally a novelist wants to be read. Only, if he is not a popular writer, he is not satisfied to take his million readers as he finds them. He does not want to be conditioned by them but rather to tell them what they ought to be.

Nietzsche declared in Human, All Too Human that artists regularly exaggerate the value of personality. Of course exaggeration is a dramatic necessity; and simplification too. If a hero does not matter his fate does not matter. If a single life is of slight importance, deaths are not especially awe-inspiring. In defense of the dramatic element, therefore, the writer has frequently insisted on assigning a definite value to reality. In this respect writers are conservative; they want old agreements and understanding to last. Your villain cannot blackmail your hero if your hero has no reputation

...more

We cannot continue to build in every novel such total systems in order that all may know what, for example, a woman experiences when her husband deserts her, what a man feels on his deathbed. We must take our chances on a belief in the psychic unity of mankind. But of course people—audiences—will not always assume what we assume,

there are so many of us, such a multitude, that it is difficult if not impossible to give every man his due measure of attention. If you demand more you are considered presumptuous and conceited. Therefore most men in their self-presentation to the world settle upon a few simple attributes and create a surface easy to characterize and to understand. Underneath, their real, complex existence takes place, their private affair. The code that protects this privacy is powerful and elaborate. Some emotions are in the course of losing their external form, and because they are not demonstrated they

...more

the rising of an imperious need abolishes all the questions. “Do you feel it necessary to do this? Then, for the love of God, do it,” says the need. If it argues at all.

Such grim energy

There are critics who assume that you must begin with order if you are to end with it. Not so. A novelist begins with disorder and disharmony and goes toward order by an unknown process of the imagination.

We are a nation devoted to facts and we don’t like to waste time with books that give the wrong dope about shipwrecks on the coast of Bohemia. We like to get things straight. Otherwise we feel that we are wasting valuable time. And if a man writes a book we think we are justified in asking him, as though we were about to hire him, about his qualifications and his experience. For we really feel that experience is intrinsically valuable and we have the same acquisitive attitude toward it as toward other things of value. Experience

By refusing to write anything with which he is not thoroughly familiar, the American writer confesses the powerlessness of the imagination and accepts his relegation to an inferior place.

imagination requires the tranquil attitude.

But it is not only ideas of evil that become destructive. Ideas of good, held in earnest, may be equally damaging to the passive thinker. His passivity puts him in self-contempt. This same contempt may estrange him from the ideas of good. He lives below them and feels dwarfed. On certain occasions a hero in thought, he has become abject in fact and cannot be blamed for feeling that he is not doing a man’s work. He reads about man’s work in the paper. Men are planning new bond issues, molding public opinion, solving the crisis of the Suez Canal. Men are active. Ideas are passive. Ideas are held

...more

impotence has received more attention from modern writers than any other subject.

For every poet now there are a hundred custodians and doctors of literature and dozens of undertakers measuring away at coffins.

Not professional study but imagination keeps imagination alive.

“All things which come to much,” he says, “whether they be books, buildings, pictures or living beings, are suggested by others of their kind.”

The argument that the novel is dying or dead is made by men who shut the door on multiplicity and distraction. They suppose the distraction to be too great for the imagination to overcome. When they speak of an agreed picture what they mean is that we are a mass civilization, doomed to be shallow and centerless.

Marx and Engels too were prophets of obsolescence. For Stalin the kulaks were obsolete; for Hitler, all the inferior breeds of men.

The writer asks himself, “Why shall I write this next thing?” It is still possible, despite all theories to the contrary, to answer, “Because it is necessary.”

The great mass of mankind breeds obedient types. They express their protests in acts of violence, not ingeniously. Moreover, your natural or talented confidence man is attracted to politics. Why be a robber, a fugitive, when you can get society to give you the key to the vaults where the greatest boodle lies?

D. H. Lawrence believed the common people of our industrial cities were like the great slave populations of the ancient empires.

there is power in a story. It testifies to the worth, the significance of an individual.

one Jewish writer (Hyman Slate in The Noble Savage) has argued that laughter, the comic sense of life, may be offered as proof of the existence of God. Existence, he says, is too funny to be uncaused.