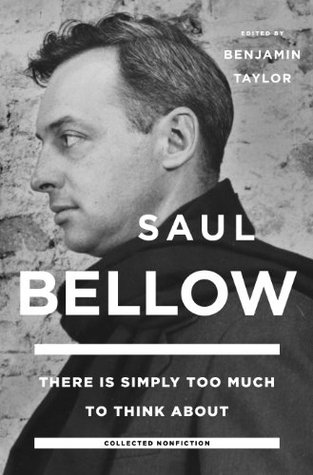

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The civilized individual is proud of his painted millstone, the burden that he believes gives him distinction. In an artist’s eyes his persona is only a rude, impoverished, mass-produced figure brought into being by a civilization in need of a working force, a reservoir of personnel, a docile public that will accept suggestion and control.

Gertrude Stein tells us in one of her lectures that we cannot read the great novels of the twentieth century, among which she includes her own The Making of Americans, for what happens next. And in fact Ulysses, Remembrance of Things Past, The Magic Mountain and The Making of Americans do not absorb us

great many novelists, even those who have concentrated on hate, like Céline, or on despair, like Kafka, have continued to perform a most important function. Their books have attempted, in not a few cases successfully, to create scale, to order experience, to give value, to make perspective and to carry us toward sources of life, toward life-giving things.

I sometimes feel that Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a sort of Robinson Crusoe for two, exploring man’s sexual resources rather than his technical ingenuity. It is every bit as moral a novel as Crusoe. Connie and Mellors work at it as hard and as conscientiously as Robinson and there are as many sermons in the one as in the other.

The attempt of writers to make perspective, to make scale and to carry us toward the sources of life, is of course the didactic intention. It involves the novelist in programs, in slogans, in political theories, religious theories and so on. Many modern novelists seem to say to themselves “what if” or “suppose that such and such were the case” and the results often show that the book was conceived in thought, in didactic purpose, rather than in the imagination.

the idea of love is more common than love and the idea of belief is more often met with than faith.

If narration is neglected by novelists like Proust and Joyce, the reasons are that for a time the drama has passed from external action to internal movement. In Proust and Joyce we are enclosed by and held within a single consciousness. In this inner realm the writer’s art dominates everything. The drama has left external action because the old ways of describing interests, of describing the fate of the individual, have lost their power. Is the sheriff a good fellow? Is our neighbor to be pitied? Are the baker’s daughters virtuous? We see such questions now as belonging to a dead system, mere

...more

Imagination, binding itself to dull viewpoints, puts an end to stories. The imagination is looking for new ways to express virtue. Society just now is in the grip of certain common falsehoods about virtue—not that anyone really believes them. And these cheerful falsehoods beget their opposites in fiction, a dark literature, a literature of victimization, of old people sitting in ash cans waiting for the breath of life to depart. This is the way things stand; only this remains to be added, that we have barely begun to comprehend what a human being is and that the baker’s daughters may have

...more

In a way it doesn’t matter what sort of line the novelist is pushing, what he is affirming. If he has nothing to offer but his didactic purpose, he is a bad writer. His ideas have ruined him.

The novel, to recover and flourish, requires new ideas about humankind. These ideas in turn cannot live in themselves. Merely asserted, they show nothing but the goodwill of the author. They must therefore be discovered and not invented. We must see them in flesh and blood.

The view attributed to Ernest Hemingway is “If you’re looking for messages, try Western Union.”

At times the moral purpose of these great writers of the nineteenth century tires us, their sermons seem too long—naïve. The crudity, disorder, ugliness and lawlessness of commercial and industrial expansion which scandalized them have been our only environment, our normalcy. And sometimes we are a little impatient with their romantic naïveté. When Emerson tells us, “Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructors in eloquence and wisdom,” we can’t help wondering what he would have made of some of the sinister intricacies of a modern organization.

Ideas, when they achieve a very high level, can easily be accepted by a busy, practical people. Why not? Sublimity never hurt anyone.

At the present time there is a sort of struggle going on between the squares and some other shape considered better. Or as I prefer to call it, between Cleans and Dirties. The Cleans want to celebrate bourgeois virtues. At least they seem to respect them—steadiness, restraint, a sense of duty. The Dirties are latter-day romantics and celebrate impulsiveness, lawless tendencies, the wisdom of the heart. The Cleans are occasionally conservative and sometimes speak for the Anglo-Saxon majority.

But in many cases the differences are superficial, and Cleans and Dirties are remarkably similar. Not unpredictably, the Cleans express destructive feelings while the Dirties, when they become intelligible, are often sentimental moralists;

Clarification, deepening, illumination are moral aims even when the means seem to readers anarchic or even loathsome. The “wild” writings of Dadaists and surrealists were intended to shock the reader into a new, more vivid wakefulness and not to fill him with disgust.

the more difficult things become, the more intensely the demand for affirmation is repeated. The dimmer, the grayer, the drearier they are, the louder the call for color and variety; and the more people cheat, the more they ask to hear about goodness.

If a novelist is going to affirm anything, he must be prepared to prove his case in close detail, reconcile it with hard facts, and he must even be prepared for the humiliation of discovering that he may have to affirm something different. The facts are stubborn and refractory and the art of the novel itself has a tendency to oppose the conscious or ideological purposes of the writer, occasionally ruining the most constructive intentions. But then, constructive intentions also ruin novels.

There was a carefree time in the history of the novel when the writer had nothing to do but to tell us what had happened. Experience in itself then pleased us; the description of experience was self-justifying. But nothing so simple now seems acceptable. It is the self, the person to whom things happen, who is perhaps not acceptable to the difficult and fastidious modern consciousness.

the idiocy of orthodox affirmation and transparent or pointless optimism ought not to provoke an equal and opposite reaction.

a species of wretchedness that is thoroughly pleased with itself.

it’s about time everyone recognized that romantic despair in this form, naggingly conscious of the absurd, is absurdly portentous, not metaphysically “absurd.” There is grandeur in cursing the heavens, but when we curse our socks we should not expect to be taken seriously.

The writer should either love or hate his subject. Tolstoy condemned neutrality or objectivity therefore as inartistic. He was contradicted by the “art for art’s sake” novelists who explicitly rejected moral purpose. Probably Flaubert is the most significant of these. He, and Joyce following him, felt that anything that might be described by us as a moral commitment would be a serious error. The artist, said Joyce, should have no apparent connection with his work. His place is in the wings, apart, paring his nails, indifferent to the passions of his creatures. Such aesthetic objectivity was an

...more

What we sense in modern literature continually is not the absence of a desire to be moral but rather a pointless, overwhelming, vague, objectless moral fervor. The benevolent excitement of certain novelists and dramatists is not an isolate literary phenomenon. What is obscurer in them than in political leaders or social planners is what they are going to be benevolent about and how they are going to be benevolent or constructive. In this sphere we see a multitude of moral purposes in wild disorder. For as long as novelists deal with ideas of good and evil, justice and injustice, social despair

...more

Novelists as different as Camus, Thomas Mann and Arthur Koestler are alike in this respect. Their art is as strong as their intellectual position—or as weak.

an art that is to be strong cannot be based on opinions. Opinions can be accepted, questioned, dismissed. A work of art can’t be questioned or dismissed.

either we want life to continue or we do not. If we don’t want to continue, why write books? The wish for death is powerful and silent. It respects actions; it has no need of words. But if we answer yes, we do want it to continue, we are liable to be asked how.

In the modern world (and romanticism is a modern phenomenon) the excited sense of the exceptional is required to bear the experience of the commonplace. An industrialized mass society cannot accommodate any sizable population of Prometheans and geniuses.

“Nothing conceivable is so petty, so insipid, so crowded with paltry interests, in one word so anti-poetic, as the life of man in the United States,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in 1840.

the individual, the single, separate self, feels severely limited, oppressed by the weight of numbers, by nature, by the conditions of life—his distinction rendered valueless by the lack of true power.

In every direction the romantic individual sees injustice, the threat of debility, sickness, senselessness and ruin. The typical hero of the later nineteenth-century novel has been robbed of his vitality by Christian idealism (in Thomas Hardy), is spoiled or destroyed by the arrangements of civilized society (in Tolstoy), decides not to get out of bed (in Goncharov) or lives under elaborate restraints (Henry James).

In the political sphere, classical liberalism holds that the sovereign Many ought to be guided by the gifted One or Few.

In these circumstances a “fact” is whatever brings men to a common level. Terror, bloodlust, greed and sexual excitement are the main facts.

He is a completely contemporary American phenomenon, bent utterly on having his own way, violently pursuing his happiness and losing none of his strength in thought.

Perhaps the fault is ours for demanding enlightenment with our usual positivistic assurance that a spiritual life ought to be a reality within our grasp.

Gabriel, the hero of Philip Roth’s Letting Go, has been brought up to lead a comfortable life but also to think of “higher things.” These “higher things” interfere somewhat with his happiness. But though the shadow of pain may pass over him as he eats and drinks, there is light enough to find the spoon. He is aware that it is somewhat degrading in a world like this to be a vulgar epicurean, a petty bourgeois creature. He reads (Gabriel is a graduate student) of noble feelings, great enterprises, sublime sensibilities and he feels it is faintly ridiculous to pursue his private ends so

...more

romanticism, which celebrated early life—the feeling heart of childhood, the emotions of adolescence.

Mr. Updike writes in the title story of his new collection, Pigeon Feathers, “things were upset, displaced, rearranged.” David, a sensitive and only child, is frightened when he picks up H. G. Wells’s Outline of History and reads that Jesus was something of a communist, “an obscure political agitator, a kind of hobo in a minor colony of the Roman Empire.”

The religion of the writer of sensibility is, of course, the religion of art.

It seems no longer necessary to weigh the world and find it wanting; one can find it wanting without going to the trouble of weighing it.

The enforced passivity of the individual confronted by the huge power of modern organizations resembles the impotence of childhood.

It commonly happens in American writing (in Hemingway and Fitzgerald among others) that the best things can be appreciated by the initiates alone, by the most in people.

Realistic writers follow a method—traceable to Montaigne—of circling over random facts, awaiting their opportunity to pounce on the essential.

It is not so much the full-fledged bourgeois who is the theme of modern comedy as the little man—the

The exploration of consciousness, introspection, self-knowledge and hypochondria, so solemnly conducted in twentieth-century literature, is treated ironically and humorously in books like The Confessions of Zeno by Italo Svevo. The inner life, the “unhappy consciousness,” the management of personal life, “alienation”—all the sad questions for which the late romantic writer reserved a special tone of disappointment and bitterness—are turned inside out by the modern comedian. Deeply subjective self-concern is ridiculed. My feelings, my early traumas, my moral seriousness, my progress, my

...more

The touchiness or hypersensitivity of various classes that develops in the course of their social ascent unfortunately results in pompousness, hypocrisy and tyranny. We begin to understand what this may mean when we hear Premier Khrushchev cry out that the younger generation of poets and painters in the Soviet Union “eat the bread of the people” and repay them with “horrible rot and dirty daubs.” This is what comes of the policy that art must serve the political and social aims of any regime or class directly.

Free public education has given the power of expression and a new understanding (in that order) to the grandsons and granddaughters of laboring illiterates. It has made them able to deplore their civilized condition.

Undeniably the human being is not what he commonly thought a generation ago. The question nevertheless remains. He is something. What is he? This question, it seems to me, modern writers have answered poorly. They have told us, indignantly or nihilistically or comically, how great our error is, but for the rest they have offered us thin fare.

The late Georges Bernanos complained that the isolated labor of writing deprived novelists of essential human contacts. This is indeed a bitter and painful privation, even if it is in some instances a temperamental preference of novelists.

I am concerned with the influence of metaphors on the human mind. Any powerful interpretation of human destiny—the Fall of Man, Apollo versus Dionysus, History as Class Struggle, the Dialectic of Eros and Death—so fixes or hypnotizes the imagination that it can see no alternatives.