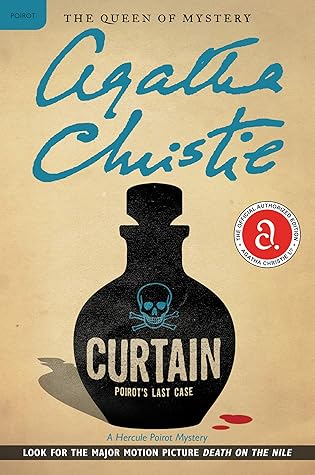

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 31 - April 21, 2025

And John isn’t any good at concealing his feelings. He doesn’t mean, of course, to be unkind, but he’s—well, mercifully for himself he’s a very insensitive sort of person. He’s no feelings and so he doesn’t expect anyone else to have them. It’s so terribly lucky to be born thick-skinned.”

Of course I know that if it wasn’t for me, he would be much freer. Sometimes, you know, I get so terribly depressed that I think what a relief it would be to end it all.”

“She won’t do anything of the kind. Don’t you worry, Captain Hastings. These ones that talk about ‘ending it all’ in a dying-duck voice haven’t the faintest intention of doing anything of the kind.”

This suited Poirot, who abhorred draughts and was always suspicious of the fresh air.

A suspicion crossed my mind that Mrs. Franklin rather liked playing different roles. At this moment she was being the loyal and hero-worshipping wife.

But that’s the sort of person John is—absolutely oblivious of his own safety.

“Given to dramatizing herself in various roles. One day the misunderstood, neglected wife, then the self-sacrificing, suffering woman who hates to be a burden on the man she loves. Today it’s the hero-worshipping helpmate. The trouble is that all the roles are slightly overdone.”

Mrs. Franklin, I reflected, was that rather feckless type of woman who always did leave things behind, shedding her possessions and expecting everybody to retrieve them as a matter of course and even, I fancied, was rather proud of herself for so doing.

Boyd Carrington, as was natural, did most of the talking, Norton putting in a word or two here and there and Judith sitting silent but closely attentive.

Someone whose mind is clear and who will take the responsibility.”

People are too afraid of responsibility. They’ll take responsibility where a dog is concerned—why not with a human being?” “Well—it’s rather different, isn’t it?” Judith said: “Yes, it’s more important.”

You can’t have people here, there, and everywhere, taking the law into their own hands, deciding matters of life and death.”

To begin with I don’t hold life as sacred as all you people do. Unfit lives, useless lives—they should be got out of the way. There’s so much mess about. Only people who can make a decent contribution to the community ought to be allowed to live. The others ought to be put painlessly away.”

“Of course it’s not. It’s really a question of courage. One just hasn’t got the guts, to put it vulgarly.”

“It’s the sort of half-baked idea one has when one is young, but fortunately one doesn’t carry it out. It remains just talk.”

“Yes, sorry if I’m being a Nosy Parker, but frankly if I were you I shouldn’t let that girl of yours see too much of him. He’s—well, his reputation isn’t very good.”

Girls can look after themselves, as the saying goes. Most of them can, too. But—well—Allerton has rather a special technique in that line.”

Don’t let it go farther, of course—but I do happen to know something pretty foul about him.”

The story of a girl, sure of herself, modern, independent. Allerton had brought all his technique to bear upon her. Later had come the other side of the picture—the story ended with a desperate girl taking her own life with an overdose of Veronal. And the horrible part was that the girl in question had been much the same type as Judith—the independent, highbrow kind. The kind of girl who when she does lose her heart, loses it with a desperation and an abandonment that the silly little fluffy type can never know.

I felt that I had no right to burden Poirot with this, my purely personal problem. It was not as though he could help in any way.

Moreover I was, as people are, convinced that any happening that occurred was connected with my own particular perplexity.

Where’s John? He said he’d got a headache and was going to walk it off. Very unlike him to have a headache. I think, you know, he’s worried about his experiments. They aren’t going right or something. I wish he’d talk more about things.”

From inside Allerton’s room I heard voices. I don’t think I meant consciously to listen though I stopped for a minute automatically outside his door. Then, suddenly, the door opened and my daughter Judith came out.

“Now, listen, Father. I do what I choose. You can’t bully me. And it’s no good ranting. I shall do exactly as I please with my life, and you can’t stop me.”

He was still with me as I turned the corner of the house. They were there. I saw Judith’s upturned face, saw Allerton’s bent down over it, saw how he took her in his arms and the kiss that followed.

“Well, then, my dear girl, that’s settled. Don’t make anymore objections. You go up to town tomorrow. I’ll say I’m running over to Ipswich to stay with a pal for a night or two. You wire from London that you can’t get back. And who’s to know of that charming little dinner at my flat? You won’t regret it, I can promise you.”

Allerton was not going to meet Judith in London tomorrow. Allerton was not going anywhere tomorrow. . . . The whole thing was really so ridiculously simple.

I tried the tablets in a little of the spirit. They dissolved easily enough. I tasted the mixture gingerly. A shade bitter perhaps but hardly noticeable. I had my plan. I should be just pouring myself out a drink when Allerton came up. I would hand that to him and pour myself out another. All quite easy and natural.

For the truth of the matter is, you see, that I sat there waiting for Allerton and that I fell asleep!

Anyway, it happened. I fell asleep there in my chair, and when I woke birds were twittering outside, the sun was up and there was I, cramped and uncomfortable, slipped down in my chair in my evening dress, with a foul taste in the mouth and a splitting head.

Melodramatic, lost to all sense of proportion. I had actually made up my mind to kill another human being.

“I shouldn’t have been caught,” I said. “I’d taken every precaution.” “That is what all murderers think. You had the true mentality! But let me tell you, mon ami, you were not as clever as you thought yourself.”

“Do nothing,” said Poirot with emphasis. “Oh, but—” “Believe me, you will do least harm by not interfering.” “If I were to tackle Allerton—” “What can you say or do? Judith is twenty-one and her own mistress.”

Do not imagine that you are clever enough, forceful enough, or even cunning enough to impose your personality on either of those two people. Allerton is accustomed to dealing with angry and impotent fathers and probably enjoys it as a good joke. Judith is not the sort of creature who can be browbeaten.

But it was true, I reflected now, that I had never heard her actually assent. No, she was too fine, too essentially good and true, to give in. She had refused the rendezvous.

“She likes to interfere with anyone else enjoying themselves. She’d like her husband all worked up, and me running round after her, and even Sir William has got to be made to feel like a brute because he ‘overtired her yesterday.’ She’s one of that kind.”

I gathered that Mrs. Franklin had been really extremely rude to her. She was the kind of woman whom nurses and servants instinctively disliked, not only because of the trouble she gave, but because of her manner of doing so.

Judith looked white and strained. She was very silent, looked vaguely about her as though lost in a dream and then went away.