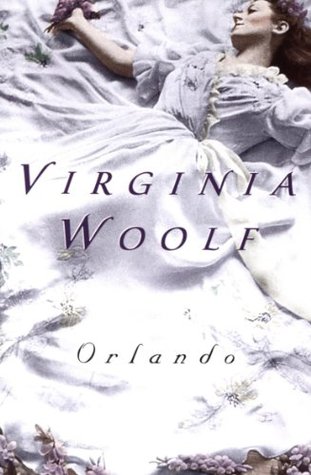

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The shade of green Orlando now saw spoilt his rhyme and split his metre.

So, after a long silence, “I am alone,” he breathed at last, opening his lips for the first time in this record. He had walked very quickly uphill through ferns and hawthorn bushes, startling deer and wild birds, to a place crowned by a single oak tree.

the heart that seemed filled with spiced and amorous gales

and held itself very upright though perhaps in pain from sciatica;

implied a pair of the finest legs that a young nobleman has ever stood upright upon;

She saw always the glistening poison drop and the long stiletto.

dust over the roofs as the icy blast struck

Shoals of eels lay motionless in a trance, but whether their state was one of death or merely of suspended animation which the warmth would revive puzzled the philosophers.

Orlando, it is true, was none of those who tread lightly the coranto and lavolta;

When the boy, for alas, a boy it must be—no woman could skate with such speed and vigour—swept almost on tiptoe past him, Orlando was ready to tear his hair with vexation that the person was of his own sex, and thus all embraces were out of the question. But the skater came closer.

Love had meant to him nothing but sawdust and cinders.

Yet perhaps it would have been better for him had he never learnt that tongue; never answered that voice; never followed the light of those eyes. . . .

What was the nauseating mixture they had poured on her plate? Did the dogs eat at the same table with the men in England?

popinjays

discharge any other of those manifold duties which the supreme lady exacts and the lover hastens to anticipate was a sight to kindle the dull eyes of age, and to make the quick pulse of youth beat faster. Yet over it all hung a cloud. The old men shrugged their shoulders.

he would leave the company as soon as they had dined, or steal away from the skaters, who were forming sets for a quadrille.

They smelt bad. Their dogs ran between her legs. It was like being in a cage. In Russia they had rivers ten miles broad on which one could gallop six horses abreast all day long without meeting a soul.

a creature soft as snow, but with teeth of steel, which bit him so savagely that his father had it killed—hence

And then they would marvel that the ice did not melt with their heat, and pity the poor old woman who had no such natural means of thawing it, but must hack at it with a chopper of cold steel.

And then, wrapped in their sables, they would talk of everything under the sun; of sights and travels; of Moor and Pagan; of this man’s beard and that woman’s skin; of a rat that fed from her hand at table; of the arras that moved always in the hall at home; of a face; of a feather. Nothing was too small for such converse, nothing was too great.

For the philosopher is right who says that nothing thicker than a knife’s blade separates happiness from melancholy; and he goes on to opine that one is twin fellow to the other; and draws from this the conclusion that all extremes of feeling are allied to madness;

So the green flame seems hidden in the emerald, or the sun prisoned in a hill.

or that she was ashamed of the savage ways of her people, for he had heard that the women in Muscovy wear beards and the men are covered with fur from the waist down; that both sexes are smeared with tallow to keep the cold out, tear meat with their fingers and live in huts where an English noble would scruple to keep his cattle;

dressed in velvet and pearls,

lit a lump of candle

Obstacles there were and hardships to be overcome. She was determined to live in Russia, where there were frozen rivers and wild horses and men, she said, who gashed each other’s throats open.

Nor was he anxious to cease his pleasant country ways of sport and tree planting; relinquish his office; ruin his career; shoot the reindeer instead of the rabbit; drink vodka instead of canary, and slip a knife up his sleeve—for

He was recalled, turning westward, by the sight of the sun, slung like an orange on the cross of St. Paul’s. It was blood red and sinking rapidly.

Sasha had been gone this hour and more.

that reminded Orlando of a scene some nights since, when he had come upon her in secret gnawing a candle end in a corner, which she had picked from the floor.

Was there not, he thought, handing her on to the ice, something rank in her, something

The main press of people, it appeared, stood opposite a booth or stage something like our Punch and Judy show upon which some kind of theatrical performance was going forward.

the words even without meaning were as wine to him.

Worms devour us.

or some woman of the quarter whose errand was nothing so innocent.

The dry frost had lasted so long that it took him a minute to realise that these were raindrops falling; the blows were the blows of the rain. At first, they fell slowly, deliberately, one by one. But soon the six drops became sixty; then six hundred; then ran themselves together in a steady spout of water. It was as if the hard and consolidated sky poured itself forth in one profuse fountain. In the space of five minutes Orlando was soaked to the skin.

With the superstition of a lover, Orlando had made out that it was on the sixth stroke that she would come.

But what was the most awful and inspiring of terror was the sight of the human creatures who had been trapped in the night and now paced their twisting and precarious islands in the utmost agony of spirit. Whether they jumped into the flood or stayed on the ice their doom was certain.

Standing knee deep in water he hurled at the faithless woman all the insults that have ever been the lot of her sex. Faithless, mutable, fickle, he called her; devil, adulteress, deceiver; and the swirling waters took his words, and tossed at his feet a broken pot and a little straw.

But the doctors were hardly wiser then than they are now, and after prescribing rest and exercise, starvation and nourishment, society and solitude, that he should lie in bed all day and ride forty miles between lunch and dinner, together with the usual sedatives and irritants, diversified, as the fancy took them, with possets of newt’s slobber on rising, and draughts of peacock’s gall on going to bed, they left him to himself, and gave it as their opinion that he had been asleep for a week.

Are they remedial measures—trances in which the most galling memories, events that seem likely to cripple life for ever, are brushed with a dark wing which rubs their harshness off and gilds them, even the ugliest, and basest, with a lustre, an incandescence? Has the finger of death to be laid on the tumult of life from time to time lest it rend us asunder? Are we so made that we have to take death in small doses daily or we could not go on with the business of living?

melancholy, of indolence, of passion, of love of solitude, to say nothing of all those contortions and subtleties of temper which were indicated on the first page,

It was the fatal nature of this disease to substitute a phantom for reality, so that Orlando, to whom fortune had given every gift—plate, linen, houses, men-servants, carpets, beds in profusion—had only to open a book for the whole vast accumulation to turn to mist.

The nine acres of stone which were his house vanished; one hundred and fifty indoor servants disappeared; his eighty riding horses became invisible; it would take too long to count the carpets, sofas, trappings, china, plate, cruets, chafing dishes and other movables often of beaten gold, which evaporated like so much sea mist under the miasma.

Memory is the seamstress, and a capricious one at that.

Thus, the most ordinary movement in the world, such as sitting down at a table and pulling the inkstand towards one, may agitate a thousand odd, disconnected fragments, now bright, now dim, hanging and bobbing and dipping and flaunting, like the underlinen of a family of fourteen on a line in a gale of wind.

Orlando paused. Memory still held before him the image of a shabby man with bright eyes. Still he looked; still he paused. It is these pauses that are our undoing. It is then that sedition enters the fortress and our troops rise in insurrection. Once before he had paused, and love with its horrid rout, its shawms, its cymbals, and its heads with gory locks torn from the shoulders had burst in. From love he had suffered the tortures of the damned. Now, again,

Every single thing, once he tried to dislodge it from its place in his mind, he found thus cumbered with other matter like the lump of glass which, after a year at the bottom of the sea, is grown about with bones and dragon-flies, and coins and the tresses of drowned women.

Sunk for a long time in profound thoughts as to the value of obscurity, and the delight of having no name, but being like a wave which returns to the deep body of the sea;

He had matter now, he thought, to fill out his peroration.