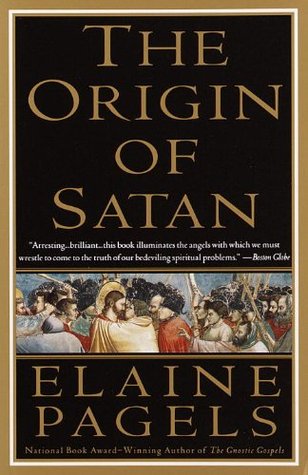

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

many scholars have pointed out: that while angels often appear in the Hebrew Bible, Satan, along with other fallen angels or demonic beings, is virtually absent.

along with diabolical colleagues like Belial and Mastema (whose Hebrew name means “hatred”), did not materialize out of the air. Instead, as we shall see, such figures emerged from the turmoil of first-century Palestine, the setting in which the Christian movement began to grow.

What interests me instead are specifically social implications of the figure of Satan: how he is invoked to express human conflict and to characterize human enemies within our own religious traditions.

The distinction between “us” and “them” occurs within our earliest historical evidence, on ancient Sumerian and Akkadian tablets, just as it exists in the language and culture of peoples all over the world. Such distinctions are charged, sometimes with attraction, perhaps more often with repulsion—or both at once. The ancient Egyptian word for Egyptian simply means “human”; the Greek word for non-Greeks, “barbarian,” mimics the guttural gibberish of those who do not speak Greek—since they speak unintelligibly, the Greeks call them barbaroi

A society does not simply discover its others, it fabricates them, by selecting, isolating, and emphasizing an aspect of another people’s life, and making it symbolize their difference.

saying of Søren Kierkegaard: “An unconscious relationship is more powerful than a conscious one.”

For nearly two thousand years, for example, many Christians have taken for granted that Jews killed Jesus and the Romans were merely their reluctant agents,

Many scholars assumed that Mark was the most historically reliable because it was the simplest in style and was written closer to the time of Jesus than the others were. But historical accuracy may not have been the gospel writers’ first consideration.

Christian writers often expanded biblical passages into whole episodes that “proved,” to the satisfaction of many believers, that events predicted by the prophets found their fulfillment in Jesus’ coming.

the gospel of Mark, as James Robinson shows, is anything but a straightforward historical narrative; rather, it is a theological treatise that assumes the form of historical biography.

One group of scholars pointed out discrepancies between Sanhedrin procedure described in the Mishnah and in the gospel accounts of Jesus’ “trial before the Sanhedrin,” and questioned the accuracy of the accounts in Mark and Matthew.

Simon Bernfield declared in 1910 that “the whole trial before the Sanhedrin is nothing but an invention of a later date,”13 a

Paul Winter in his influential book On the Trial of Jesus, published in 1961, argued that it was the Romans who executed Jesus, on political grounds, not religious ones.

the first Christian gospel was probably written during the last year of the war, or the year it ended.

We cannot fully understand the New Testament gospels until we recognize that they are, in this sense, wartime literature.

Paul died c. 64–65

Mark insists that Jesus’ followers had no quarrel with the Romans but with the Jewish leaders—the

The stark events of Jesus’ life and death cannot be understood, he suggests, apart from the clash of supernatural forces that Mark sees being played out on earth in Jesus’ lifetime.

Mark frames his narrative at its beginning and at its climax with episodes in which Satan and his demonic forces retaliate against God by working to destroy Jesus.

From that moment on, Mark says, even after Jesus left the wilderness and returned to society, the powers of evil challenged and attacked him at every turn, and he attacked them back, and won.

All of the New Testament gospels, with considerable variation, depict Jesus’ execution as the culmination of the struggle between good and evil—between God and Satan—that began at his baptism.

These gospels carry their writers’ powerful conviction that Jesus’ execution, which had seemed to signal the victory of the forces of evil, actually heralds their ultimate annihilation and ensures God’s final victory.

The figure of Satan becomes, among other things, a way of characterizing one’s actual enemies as the embodiment of transcendent forces.

Yet who actually were Jesus’ enemies? What we know historically suggests that they were the Roman governor and his soldiers.

The Roman authorities, ever watchful for any hint of sedition, were ruthless in suppressing it.

During the first century the Romans arrested and crucified thousands of Jews charged with sedition—often, Philo says, without trial.

Mark’s point is to demonstrate that, as he says, Jesus “taught as one who had authority, and not as the scribes” (1:22).

He traveled throughout Galilee “preaching in the synagogues and casting out demons,” for, as he explains to Simon, Andrew, James, and John, who gather around him, “that is what I came to do”

The Essenes took the preaching of repentance and God’s coming judgment to mean that Jews must separate themselves from such polluting influences and return to strict observance of God’s law—especially the Sabbath and kosher laws that marked them off from the Gentiles as God’s holy people.

Instead of fasting, like other devout Jews, Jesus ate and drank freely. And instead of scrupulously observing Sabbath laws, Jesus excused his disciples when they broke them:

Instead of postponing the healing for a day, Jesus had chosen deliberately to defy his critics by performing it on the Sabbath.

For Mark the secret meaning of such conflict is clear. Those who are offended and outraged by Jesus’ actions do not know that Jesus is impelled by God’s spirit to contend against the forces of evil, whether those forces manifest themselves in the invisible demonic presences who infect and possess people, or in his actual human opponents. When the Pharisees and Herodians conspire to kill Jesus, they themselves, Mark suggests, are acting as agents of evil.

Although he often criticizes the disciples—in 8:33 he even accuses Peter of playing Satan’s role—Jesus shares secrets with them that he hides from outsiders, for the latter, he says, quoting Isaiah, are afflicted with impenetrable spiritual blindness.

Mark wants to show that although Jesus discards traditional kosher (“purity”) laws, he advocates instead purging the “heart”—that is, impulses, desires, and imagination.

“The chief priests and scribes … will condemn [the Son of man] to death, and hand him over to the nations, and

“ ‘You have heard his blasphemy. What is your decision?’ And they all condemned him as deserving death” (14:64). Many scholars have commented on the historical implausibility of this account.29 Did the Sanhedrin conduct a trial that violated its own legal practices concerning examining witnesses, self-incrimination, courtroom procedure, and sentencing?

why does Mark go on to add a second version of the council meeting to discuss this case—a meeting that takes place the following morning, as if nothing had happened the night before?

Mark’s second version, which agrees with Luke’s, sounds more likely—that

the council convened in the morning, and decided that the prisoner should be kept in custody and turned over to Pilate to face charges.

probably wrote the first version to emphasize his primary point: that Pilate merely ratified a previous Jewish verdict, and carried out a death sentence that he himself neither ordered nor approved—but a sentence unanimously pronounced by the entire leadership of the Jewish people.

Mark and his fellow believers, as followers of a convicted criminal, knew that such allegiance would arouse suspicion and invite reprisals.

Mark again confronts his audience with the question that pervades his entire narrative: Who recognizes the spirit in Jesus as divine, and who does not? Who stands on God’s side, and who on Satan’s? By contrasting Jesus’ courageous confession with Peter’s denial, Mark draws a dramatic picture of the choice confronting Jesus’ followers: they must take sides in a war that allows no neutral ground.

Mark says that when Jesus refused to answer his questions, Pilate, instead of demonstrating anger or even impatience, “was amazed”

according to Mark, Pilate never pronounces sentence, and never actually orders the execution.

the chief priests are in charge: it is they who make accusations and it is they who stir up the crowds, whose vehemence forces Jesus’ execution upon a reluctant Pilate.

Philo, referring to the situation of the Jewish community in Judea, describes governor Pilate as a man of “inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition,” and lists as typical features of his administration “greed, violence, robbery, assault, abusive behavior, frequent executions without trial, and endless savage ferocity.”37 Philo writes to persuade Roman rulers to uphold the privileges of Jewish communities, as he claims that the emperor Tiberius had done. In this letter, Philo sees Pilate as the image of all that can go wrong with Roman administration of Jewish provinces.

Josephus records several episodes that show Pilate’s contempt for Jewish religious sensibilities. Pilate’s predecessors, for example, recognizing that Jews considered images of the emperor to be idolatrous, had instituted the practice of choosing for the Roman garrison in Jerusalem a military unit whose standards did not carry such images. But when Pilate was appointed governor he deliberately violated this precedent. First he ordered the existing garrison to leave; then he led to Jerusalem a replacement unit whose standards displayed imperial images, timing his arrival to coincide with the

...more

the holy city, they gathered in the streets to protest. A great crowd followed Pilate back to Caesarea and stood outside his residence, pleading with him to remove them. Since the standards always accompanied the military unit, this amounted to a demand that Pilate withdraw the garrison. When Pilate refused, the crowds continued to demonstrate. After five days, Pilate, exasperated but adamant, decided to force an end to the demonstrations. Pretending to offer the demonstrators a formal hearing, he summoned them to appear before him in the stadium. There Pilate had amassed soldiers, ordered

...more

The Jews had won a decisive victory in the first round against their new governor, but now they knew what sort of man they were up against, and thereafter anything he did was liable to be suspect.…

Roman authorities also respected Jewish sensitivity by banning images considered idolatrous from coins minted in Judea. Only during Pilate’s administration was this practice violated: coins depicting pagan cult symbols have been found dated 29–31 C.E