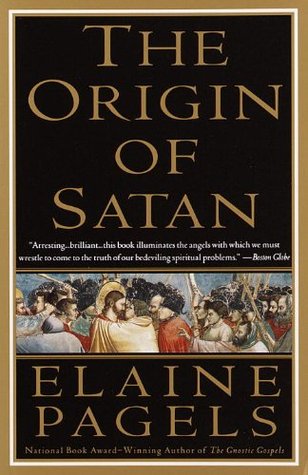

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Pilate next decided to build an aqueduct in Jerusalem. But to finance the project, he appropriated money from the Temple treasury, an act of sacrilege even from the Roman point of view, since the Temple funds were, by law, regarded as sacrosanct.41 This direct assault upon the Temple and its treasury aroused vehement opposition. When Pilate next visited Jerusalem, he was met with larger demonstrations than ever; now the angry crowds became abusive and threatening. Anticipating trouble, Pilate had ordered soldiers to dress in plain clothes, conceal their weapons, and mingle with the people.

...more

Pilate angered his subjects by dedicating golden shields in the Herodian palace in Jerusalem. We cannot be certain what occasioned the protest; the scholar B. C. McGinny suggests that the shields were dedicated to the “divine” emperor, a description that would have incensed many Jews.43 Again Pilate faced popular protest: a crowd assembled, led by four Herodian princes. When Pilate refused to remove the shields, perhaps claiming he was acting only out of respect for the emperor, Josephus says, they replied, “Do not take [the emperor] Tiberius as your pretext for outraging the nation; he does

...more

Five years later, when a Samaritan leader assembled a large multitude, some of them armed, to gather and wait for a sign from God, Pilate immediately sent troops to monitor the situation. The troops blockaded the crowd, killing some and capturing others, while the rest fled. Pilate ordered the ringleaders executed.

Pilate’s rule ended abruptly when the legate of Syria finally responded to repeated protests by stripping Pilate of his commission and dispatching a man from his own staff to serve as governor in his place. Pilate was ordered to return to Rome at once to answer charges against him, and disappeared from the historical record.

Mark, as we have seen, presents a Pilate not only as a man too weak to withstand the shouting of a crowd, but also as one solicitous to ensure justice in the case of a Jewish prisoner whom the Jewish leaders want to destroy.

Beelzebub,

Mark’s relationship with the Jewish community as a whole, for, as we shall see, the figure of Satan, as it emerged over the centuries in Jewish tradition, is not a hostile power assailing Israel from without, but the source and representation of conflict within the community.

Israel first received its identity through election, when “the Lord” suddenly revealed himself to Abraham, ordering him to leave his home country, his family, and his ancestral gods, and promising him, in exchange for exclusive loyalty, a new national heritage, with a new identity: “I will make you a great nation, and I will make your name great … and whoever blesses you I will bless; and whoever curses you I will curse” (Gen. 12:3).

most often they identified their Jewish enemies with an exalted, if treacherous, member of the divine court whom they called the satan.

satan is not an animal or monster but one of God’s angels, a being of superior intelligence and status; apparently the Israelites saw their intimate enemies not as beasts and monsters but as superhuman beings whose superior qualities and insider status could make them more dangerous than the alien enemy.

Satan never appears as Western Christendom has come to know him, as the leader of an “evil empire,” an army of hostile spirits who...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

he appears in the book of Numbers and in Job as one of God’s obedient servants—a messenger, or angel, a word that translates the Hebrew term for messenger (mal’āk) into Greek (angelos).

In Hebrew, the angels were often called “sons of God” (benē ’elōhīm), and were envisioned as the hierarchical ranks of a great army, or the staff of a royal court.

In biblical sources the Hebrew term the satan describes an adversarial role. It is not the name...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Hebrew storytellers as early as the sixth century B.C.E. occasionally introduced a supernatural character whom they called the satan, what they meant was any one of the angels sent by God for the speci...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The root śṭn means “one who opposes, obstructs, or acts as adversary.” (The Greek term diabolos, later translated “devil,” literally means “one w...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Hebrew storytellers often attribute misfortunes to human sin. Some, however, also invoke this supernatural character, the satan, who, by God’s own order or permission, blocks or opposes human plans and desires.

But this messenger is not necessarily malevolent.

God sends him, like the angel of death, to perform...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“If the path is bad, an obstruction is good.”9 Thus the satan may simply have been sent by the Lord to protect a person from worse harm.

Balaam saddled his ass and set off, “but God’s anger was kindled because he went; and the angel of the Lord took his stand in the road as his satan” [le-śā n-lō]—that is, as his adversary, or his obstructor.

Then the satan rebukes Balaam, and speaks for his master, the Lord: “Why have you struck your ass three times? Behold, I came here to oppose you, because your way is evil in my eyes; and the ass saw me.… If she had not turned away from me, I would surely have killed you right then, and let her live” (22:31–33).

the Hebrew word “to roam,” suggesting that the satan’s special role in the heavenly court is that of a kind of roving intelligence agent,

like those whom many Jews of the time would have known—and detested—from the king of Persia’s elaborate system of secret police and intelligence officers.

The Lord agrees to test Job, authorizing the satan to afflict Job with devastating loss, but defining precisely how far he may go:

Here the satan terrifies and harms a person but, like the angel of death, remains an angel, a member of the heavenly court, God’s obedient servant.

Job was written (c. 550 B.C.E.),

other biblical writers invoked the satan to account for divi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

David’s introduction of taxation aroused vehement and immediate opposition—opposition that began among the very army commanders ordered to carry it out. Joab, David’s chief officer, objected, and warned the king that what he was proposing to do was evil.

the author of 1 Chronicles suggests that a supernatural adversary within the divine court had managed to infiltrate the royal house and lead the king himself into sin: “The satan stood up against Israel, and incited David to number the people” (1 Chron. 21:1).

the chronicler insists that the king was nevertheless personally responsible—and

Here the satan is invoked to account for the division and destruction that King David’s order aroused within Israel.

the prophet Zechariah had depicted the satan inciting factions among the people.

Many of those who had remained saw the former exiles not only as agents of the Persian king but as determined to retrieve the power and land they had been forced to relinquish when they were deported. Many resented the returnees’ plan to take charge of the priestly offices and to “purify” the Lord’s worship.

The Lord showed me Joshua, the high priest, standing before the angel of the Lord, and the satan standing at his right hand to accuse him. The Lord said to the satan, “The Lord rebuke you, O satan! The Lord who has chosen Jerusalem rebuke you” (Zech. 3:1–2).

Here the satan speaks for a disaffected—and unsuccessful—party against another party of fellow Israelites.

the Syrian king Antiochus Epiphanes, suspecting resistance to his rule, decided to eradicate every trace of the Jews’ peculiar and “barbaric” culture. First he outlawed circumcision, along with study and observance of Torah. Then he stormed the Jerusalem Temple and desecrated it by rededicating it to the Greek god Olympian Zeus.

The old village priest Mattathias rose up and killed a Jew who was about to obey the Syrian king’s command. Then he killed the king’s commissioner and fled with his sons to the hills—an act of defiance that precipitated the revolt led by Mattathias’s son Judas Maccabeus.16

Many wanted their sons to have a Greek education.

many other Jews, perhaps the majority of the population of Jerusalem and the countryside—tradespeople, artisans, and farmers—detested these “Hellenizing Jews” as traitors to God and Israel alike.

The revolt ignited by old Mattathias encouraged people to resist Antiochus’s orders, even at the risk of death, and oust the foreign rulers.

After intense fighting, the Jewish armies finally won a decisive victory. They celebrated by purifying and rededicating the Temple in a ceremony commemorated, ev...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Jews resumed control of the Temple, the priesthood, and the government; but after the foreigners had retreated, internal conflicts remained, especially ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the more rigorously separatist party dominated by the Maccabees opposed the Hellenizing party. The former, having...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Although originally identified with their Maccabean ancestors, successive generations of the family abandoned the austere habits of their predecessors. Two generations after the Maccabean victory, the party of Pharisees, advocating increased religious rigor, challenged the Hasmoneans.

the Pharisees, backed by tradespeople and farmers, despised the Hasmoneans as having become essentially secular rulers who had abandoned Israel’s ancestral ways.

The Pharisees demanded that the Hasmoneans relinquish the high priesthood to those who deserved it—people like themselves, who strove...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

other, more radical dissident groups joined the Pharisees in denouncing the great high prie...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Such groups were anything but uniform: they were fractious and diverse, and with the passage of time included various groups of Essenes, the monastic community at Kirbet Qûmran, as well as their allies in the towns, and the followers of Jesus of Nazareth. What these groups shared was their opposit...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

What mattered primarily, these rigorists claimed, was not whether one was Jewish—this they took for granted—but rather “which of us [Jews] really are on God’s side” and which had “walked in the ways of the nations,” that is, adopted foreign cultural and commercial practices.