More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 8 - December 11, 2021

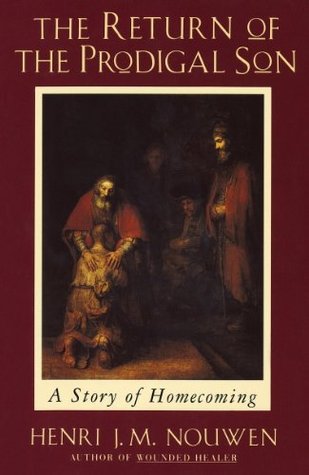

I felt drawn by the intimacy between the two figures, the warm red of the man’s cloak, the golden yellow of the boy’s tunic, and the mysterious light engulfing them both. But, most of all, it was the hands—the old man’s hands—as they touched the boy’s shoulders that reached me in a place where I had never been reached before.

But, beneath or beyond all that, “coming home” meant, for me, walking step by step toward the One who awaits me with open arms and wants to hold me in an eternal embrace.

It is a huge work in oil on canvas, eight feet high by six feet wide. It took me a while to simply be there, simply

I had become more aware of the four figures, two women and two men, who stood around the luminous space where the father welcomed his returning son.

But had I, myself, really ever dared to step into the center, kneel down, and let myself be held by a forgiving God?

had never fully given up the role of bystander.

I nevertheless kept choosing over and over again the position of the outsider looking in. Sometimes this looking-in was a curious looking-in, sometimes a jealous looking-in, sometimes an anxious looking-in, and, once in a while, even a loving looking-in. But giving up the somewhat safe position of the critical observer seemed like a great leap into totally unknown territory. I so much wanted to keep some control over my spiritual journey, to remain able to predict at least a part of the outcome, that relinquishing the security of the observer for the vulnerability of the returning son seemed

...more

The two women standing behind the father at different distances, the seated man staring into space and looking at no one in particular, and the tall man standing erect and looking critically at the event on the platform in front of him—they all represent different ways of not getting involved.

It is the place of light, the place of truth, the place of love. It is the place where I so much want to be, but am so fearful of being. It is the place where I will receive all I desire, all that I ever hoped for, all that I will ever need, but it is also the place where I have to let go of all I most want to hold on to. It is the place that confronts me with the fact that truly accepting love, forgiveness, and healing is often much harder than giving it. It is the place beyond earning, deserving, and rewarding. It is the place of surrender and complete trust.

The journey from teaching about love to allowing myself to be loved proved much longer than I realized.

Coming home and staying there where God dwells, listening to the voice of truth and love, that was, indeed, the journey I most feared because I knew that God was a jealous lover who wanted every part of me all the time. When would I be ready to accept that kind of love?

The first phase was my experience of being the younger son.

Frankly, I had never thought of myself as the elder son, but once Bart confronted me with that possibility, countless ideas started running through my head. Beginning with the simple fact that I am, indeed, the eldest child in my own family, I came to see how I had lived a quite dutiful life.

“Whether you are the younger son or the elder son, you have to realize that you are called to become the father.” Her words struck me like a thunderbolt because, after all my years of living with the painting and looking at the old man holding his son, it had never occurred to me that the father was the one who expressed most fully my vocation in life.

the idea of being like the old man who had nothing to lose because he had lost all, and only to give, overwhelmed me with fear. Nevertheless, Rembrandt died when he was sixty-three years old and I am a lot closer to that age than to the age of either of the two sons. Rembrandt was willing to put himself in the father’s place; why not I?

The more I read about it and look at it, the more I see it as a final statement of a tumultuous and tormented life. Together

As I look at the prodigal son kneeling before his father and pressing his face against his chest, I cannot but see there the once so self-confident and venerated artist who has come to the painful realization that all the glory he had gathered for himself proved to be vain glory. Instead of the rich garments with which the youthful Rembrandt painted himself in the brothel, he now wears only a torn undertunic covering his emaciated body, and the sandals, in which he had walked so far, have become worn out and useless.

Moving my eyes from the repentant son to the compassionate father, I see that the glittering light reflecting from golden chains, harnesses, helmets, candles, and hidden lamps has died out and been replaced by the inner light of old age. It is the movement from the glory that seduces one into an ever greater search for wealth and popularity to the glory that is hidden in the human soul and surpasses death.

Only when I have the courage to explore in depth what it means to leave home, can I come to a true understanding of the return.

The soft yellow-brown of the son’s underclothes looks beautiful when seen in rich harmony with the red of the father’s cloak, but the truth of the matter is that the son is dressed in rags that betray the great misery that lies behind him. In the context of a compassionate embrace, our brokenness may appear beautiful, but our brokenness has no other beauty but the beauty that comes from the compassion that surrounds it.

the son’s manner of leaving is tantamount to wishing his father dead.

the son asks not only for the division of the inheritance, but also for the right to dispose of his part.

The “distant country” is the world in which everything considered holy at home is disregarded.

the Hermitage painting, made about thirty years later, is one of utter stillness. The father’s touching the son is an everlasting blessing; the son resting against his father’s breast is an eternal peace.

Leaving home is, then, much more than an historical event bound to time and place. It is a denial of the spiritual reality that I belong to God with every part of my being, that God holds me safe in an eternal embrace, that I am indeed carved in the palms of God’s hands and hidden in their shadows. Leaving home means ignoring the truth that God has “fashioned me in secret, moulded me in the depths of the earth and knitted me together in my mother’s womb.” Leaving home is living as though I do not yet have a home and must look far and wide to find one.

Home is the center of my being where I can hear the voice that says: “You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests”—the same voice that gave life to the first Adam and spoke to Jesus,

As the Beloved, I can confront, console, admonish, and encourage without fear of rejection or need for affirmation. As the Beloved, I can suffer persecution without desire for revenge and receive praise without using it as a proof of my goodness. As the Beloved, I can be tortured and killed without ever having to doubt that the love that is given to me is stronger than death. As the Beloved, I am free to live and give life, free also to die while giving life.

Faith is the radical trust that home has always been there and always will be there. The somewhat stiff hands of the father rest on the prodigal’s shoulders with the everlasting divine blessing: “You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests.”

Why should I leave the place where all I need to hear can be heard? The more I think about this question, the more I realize that the true voice of love is a very soft and gentle voice speaking to me in the most hidden places of my being. It is not a boisterous voice, forcing itself on me and demanding attention. It is the voice of a nearly blind father who has cried much and died many deaths. It is a voice that can only be heard by those who allow themselves to be touched.

Anger, resentment, jealousy, desire for revenge, lust, greed, antagonisms, and rivalries are the obvious signs that I have left home. And that happens quite easily. When I pay careful attention to what goes on in my mind from moment to moment, I come to the disconcerting discovery that there are very few moments during my day when I am really free from these dark emotions, passions, and feelings.

As long as I keep running about asking: “Do you love me? Do you really love me?” I give all power to the voices of the world and put myself in bondage because the world is filled with “ifs.” The world says: “Yes, I love you if

I am the prodigal son every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found. Why do I keep ignoring the place of true love and persist in looking for it elsewhere? Why do I keep leaving home where I am called a child of God, the Beloved of my Father?

I now see how much more is taking place than a mere compassionate gesture toward a wayward child. The great event I see is the end of the great rebellion. The rebellion of Adam and all his descendants is forgiven, and the original blessing by which Adam received everlasting life is restored. It seems to me now that these hands have always been stretched out—even when there were no shoulders upon which to rest them.

Here the mystery of my life is unveiled. I am loved so much that I am left free to leave home. The blessing is there from the beginning. I have left it and keep on leaving it. But the Father is always looking for me with outstretched arms to receive me back and whisper again in my ear: “You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests.”

The father and the tall man observing the scene wear wide red cloaks, giving them status and dignity. The kneeling son has no cloak. The yellow-brown, torn undergarment just covers his exhausted, worn-out body from which all strength is gone.

The only remaining sign of dignity is the short sword hanging from his hips—the badge of his nobility. Even in the midst of his debasement, he had clung to the truth that he still was the son of his father.

The farther I run away from the place where God dwells, the less I am able to hear the voice that calls me the Beloved, and the less I hear that voice, the more entangled I become in the manipulations and power games of the world.

It goes somewhat like this: I am not so sure anymore that I have a safe home, and I observe other people who seem to be better off than I. I wonder how I can get to where they are. I try hard to please, to achieve success, to be recognized. When I fail, I feel jealous or resentful of these others. When I succeed, I worry that others will be jealous or resentful of me. I become suspicious or defensive and increasingly afraid that I won’t get what I so much desire or will lose what I already have. Caught in this tangle of needs and wants, I no longer know my own motivations. I feel victimized by

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This awareness of and confidence in his father’s love, misty as it may have been, gave him the strength to claim for himself his sonship, even though that claim could not be based on any merit.

Constantly I am tempted to wallow in my own lostness and lose touch with my original goodness, my God-given humanity, my basic blessedness, and thus allow the powers of death to take charge.

In contrast to the prodigal, they let the darkness absorb them so completely that there is no light left to turn toward and return to. They might not kill themselves physically, but spiritually they are no longer alive.

I am seldom without some imaginary encounter in my head in which I explain myself, boast or apologize, proclaim or defend, evoke praise or pity. It seems that I am perpetually involved in long dialogues with absent partners, anticipating their questions and preparing my responses. I am amazed by the emotional energy that goes into these inner ruminations and murmurings. Yes, I am leaving the foreign country. Yes, I am going home … but why all this preparation of speeches which will never be delivered?

Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think about his love as conditional and about home as a place I am not yet fully sure of.

I realize my failures and know that I have lost the dignity of my sonship, but I am not yet able to fully believe that where my failings are great, “grace is always greater.” Still clinging to my sense of worthlessness, I project for myself a place far below that which belongs to the son. Belief in total, absolute forgiveness does not come readily. My human experience tells me that forgiveness boils down to the willingness of the other to forgo revenge and to show me some measure of charity.

There is repentance, but not a repentance in the light of the immense love of a forgiving God. It is a self-serving repentance that offers the possibility of survival. I know this state of mind and heart quite well.

One of the greatest challenges of the spiritual life is to receive God’s forgiveness.

“Unless you turn and become like little children you will never enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” Jesus does not ask me to remain a child but to become one.

And as I reach home and feel the embrace of my Father, I will realize that not only heaven will be mine to claim, but that the earth as well will become my inheritance, a place where I can live in freedom without obsessions and compulsions.

“This is the head of a baby who just came out of his mother’s womb. Look, it is still wet, and the face is still fetus-like.”

The eternal Son became a child so that I might become a child again and so re-enter with him into the Kingdom of the Father. “In all truth I tell you,” Jesus said to Nicodemus, “no one can see the Kingdom of God without being born from above.”