More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 8 - December 11, 2021

the “return” of the prodigal becomes the return of the Son of God who has drawn all people into himself and brings them home to his heavenly Father. As Paul says: “God wanted all fullness to be found in him and through him to reconcile all things to him, everything in heaven and everything on earth.”

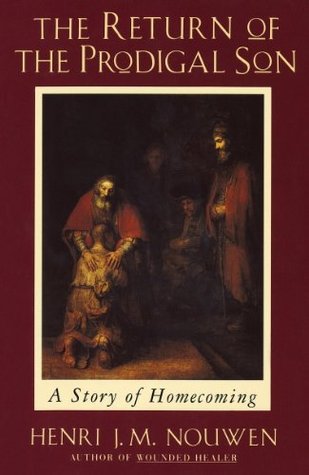

Rembrandt’s painting becomes more than the mere portrayal of a moving parable. It becomes the summary of the history of our salvation.

They add a restraining note to the painting and prevent any notions of a quick, romantic solution to the question of spiritual reconciliation. The journey of the younger son cannot be separated from that of his elder brother.

the parable makes it clear that the elder son is not yet home when the father embraces his lost son and shows him his mercy.

Barbara Joan Haeger’s “The Religious Significance of Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son.”

The seated man beating his breast and looking at the returning son is a steward representing the sinners and tax collectors, while the standing man looking at the father in a somewhat enigmatic way is the elder son, representing the Pharisees and scribes.

painting not only the younger son in the arms of his father, but also the elder son who can still choose for or against the love that is offered to him, Rembrandt presents me with the “inner drama of the soul”—his as well as my own. Just as the parable

Rembrandt is as much the elder son of the parable as he is the younger. When, during the last years of his life, he painted both sons in his Return of the Prodigal Son, he had lived a life in which neither the lostness of the younger son nor the lostness of the elder son was alien to him. Both needed healing and forgiveness. Both needed to come home. Both needed the embrace of a forgiving father.

But from the story itself, as well as from Rembrandt’s painting, it is clear that the hardest conversion to go through is the conversion of the one who stayed home.

It is true that the “return” is the central event of the painting; however, it is not situated at the physical center of the canvas. It takes place at the left side of the painting, while the tall, stern elder son dominates the right side. There is a large open space separating the father and his elder son, a space that creates a tension asking for resolution.

But what a painful difference between the two! The father bends over his returning son. The elder son stands stiffly erect, a posture accentuated by the long staff reaching from his hand to the floor. The father’s mantle is wide and welcoming; the son’s hangs flat over his body. The father’s hands are spread out and touch the homecomer in a gesture of blessing; the son’s are clasped together and held close to his chest. There is light on both faces, but the light from the father’s face flows through his whole body—especially his hands—and engulfs the younger son in a great halo of luminous

...more

they often also experience, quite early in life, a certain envy toward their younger brothers and sisters, who seem to be less concerned about pleasing and much freer in “doing their own thing.”

It is strange to say this, but, deep in my heart, I have known the feeling of envy toward the wayward son. It is the emotion that arises when I see my friends having a good time doing all sorts of things that I condemn. I called their behavior reprehensible or even immoral, but at the same time I often wondered why I didn’t have the nerve to do some of it or all of it myself.

There are many elder sons and elder daughters who are lost while still at home. And it is this lostness—characterized by judgment and condemnation, anger and resentment, bitterness and jealousy—that is so pernicious and so damaging to the human heart.

Looking deeply into myself and then around me at the lives of other people, I wonder which does more damage, lust or resentment? There is so much resentment among the “just” and the “righteous.” There is so much judgment, condemnation, and prejudice among the “saints.” There is so much frozen anger among the people who are so concerned about avoiding “sin.”

It is the complaint that cries out: “I tried so hard, worked so long, did so much, and still I have not received what others get so easily. Why do people not thank me, not invite me, not play with me, not honor me, while they pay so much attention to those who take life so easily and so casually?”

A complainer is hard to live with, and very few people know how to respond to the complaints made by a self-rejecting person. The tragedy is that, often, the complaint, once expressed, leads to that which is most feared: further rejection.

Once the self-rejecting complaint has formed in us, we lose our spontaneity to the extent that even joy can no longer evoke joy in us.

Joy and resentment cannot coexist. The music and dancing, instead of inviting to joy, become a cause for even greater withdrawal.

The only sign of a party is the relief of a seated flute player carved into the wall against which one of the women (the prodigal’s mother?) leans. In place of the party, Rembrandt painted light, the radiant light that envelops both father and son. The joy that Rembrandt portrays is the still joy that belongs to God’s house.

Neither Rembrandt’s painting nor the parable it portrays tells us about the elder son’s final willingness to let himself be found.

Jesus confronted the Pharisees and scribes not only with the return of the prodigal son, but also with the resentful elder son. It must have come as a shock to these dutiful religious people. They finally had to face their own complaint and choose how they would respond to God’s love for the sinners. Would they be willing to join them at the table as Jesus did? It was and still is a real challenge: for them, for me, for every human being who is caught in resentment and tempted to settle on a corn-plaintive way of life.

And it seems that just as I want to be most selfless, I find myself obsessed about being loved. Just when I do my utmost to accomplish a task well, I find myself questioning why others do not give themselves as I do. Just when I think I am capable of overcoming my temptations, I feel envy toward those who gave in to theirs. It seems that wherever my virtuous self is, there also is the resentful complainer.

Can the elder son in me come home? Can I be found as the younger son was found? How can I return when I am lost in resentment, when I am caught in jealousy, when I am imprisoned in obedience and duty lived out as slavery? It is clear that alone, by myself, I cannot find myself.

I can only be healed from above, from where God reaches down. What is impossible for me is possible for God. “With God, everything is possible.”

As I look at the lighted face of the elder son, and then at his darkened hands, I sense not only his captivity, but also the possibility of liberation.

The Father’s love does not force itself on the beloved. Although he wants to heal us of all our inner darkness, we are still free to make our own choice to stay in the darkness or to step into the light of God’s love.

Arthur Freeman writes: The father loves each son and gives each the freedom to be what he can, but he cannot give them freedom they will not take nor adequately understand. The father seems to realize, beyond the customs of his society, the need of his sons to be themselves. But he also knows their need for his love and a “home.” How their stories will be completed is up to them. The fact that the parable is not completed makes it certain that the father’s love is not dependent upon an appropriate completion of the story. The father’s love is only dependent on himself and remains part of his

...more

Jesus shows a distinct preference for those who are marginal in society—the poor, the sick, and the sinners—but I am certainly not marginal. The painful question that arises for me out of the Gospel is: “Have I already had my reward?” Jesus is very critical of those who “say their prayers standing up in their synagogues and at street corners for people to see them.” Of them, he says: “In truth I tell you, they have had their reward.”

The harsh and bitter reproaches of the son are not met with words of judgment. There is no recrimination or accusation. The father does not defend himself or even comment on the elder son’s behavior. The father moves directly beyond all evaluations to stress his intimate relationship with his son when he says: “You are with me always.” The father’s declaration of unqualified love eliminates any possibility that the younger son is more loved than the elder. The elder son has never left the house. The father has shared everything with him. He has made him part of his daily life, keeping nothing

...more

The joy at the dramatic return of the younger son in no way means that the elder son was less loved, less appreciated, less favored. The father does not compare the two sons. He loves them both with a complete love and expresses that love according to their individual journeys.

With the same love, he sees the obedience of the elder son, even when it is not vitalized by passion. With the younger son there are no thoughts of better or worse, more or less, just as there are no measuring sticks with the elder son. The father responds to both according to their uniqueness. The return of the younger son makes him call for a joyful celebration. The return of the elder son makes him extend an invitation to full participation in that joy.

I know the pain of this predicament. In it, everything loses its spontaneity. Everything becomes suspect, self-conscious, calculated, and full of second-guessing. There is no longer any trust. Each little move calls for a countermove; each little remark begs for analysis; the smallest gesture has to be evaluated. This is the pathology of the darkness.

The story of the prodigal son is the story of a God who goes searching for me and who doesn’t rest until he has found me. He urges and he pleads. He begs me to stop clinging to the powers of death and to let myself be embraced by arms that will carry me to the place where I will find the life I most desire.

The question before us is simply: What can we do to make the return possible? Although God himself runs out to us to find us and bring us home, we must not only recognize that we are lost, but also be prepared to be found and brought home. How? Obviously not by just waiting and being passive. Although we are incapable of liberating ourselves from our frozen anger, we can allow ourselves to be found by God and healed by his love through the concrete and daily practice of trust and gratitude. Trust and gratitude are the disciplines for the conversion of the elder son.

Without trust, I cannot let myself be found. Trust is that deep inner conviction that the Father wants me home. As long as I doubt that I am worth finding and put myself down as less loved than my younger brothers and sisters, I cannot be found. I have to keep saying to myself, “God is looking for you. He will go anywhere to find you. He loves you, he wants you home, he cannot rest unless he has you with him.”

resentment. Resentment and gratitude cannot coexist, since resentment blocks the perception and experience of life as a gift. My resentment tells me that I don’t receive what I deserve. It always manifests itself in envy.

Gratitude as a discipline involves a conscious choice. I can choose to be grateful even when my emotions and feelings are still steeped in hurt and resentment.

There is the option to look into the eyes of the One who came out to search for me and see therein that all I am and all I have is pure gift calling for gratitude.

Estonian proverb that says: “Who does not thank for little will not thank for much.”

The leap of faith always means loving without expecting to be loved in return, giving without wanting to receive, inviting without hoping to be invited, holding without asking to be held. And every time I make a little leap, I catch a glimpse of the One who runs out to me and invites me into his joy, the joy in which I can find not only myself, but also my brothers and sisters.

What gives Rembrandt’s portrayal of the father such an irresistible power is that the most divine is captured in the most human. I see a half-blind old man with a mustache and a parted beard, dressed in a gold-embroidered garment and a deep red cloak, laying his large, stiffened hands on the shoulders of his returning son. This is very specific, concrete, and describable.

The heart of the father burns with an immense desire to bring his children home. Oh, how much would he have liked to talk to them, to warn them against the many dangers they were facing, and to convince them that at home can be found everything that they search for elsewhere. How much would he have liked to pull them back with his fatherly authority and hold them close to himself so that they would not get hurt. But his love is too great to do any of that.

As Father, the only authority he claims for himself is the authority of compassion. That authority comes from letting the sins of his children pierce his heart. There is no lust, greed, anger, resentment, jealousy, or vengeance in his lost children that has not caused immense grief to his heart. The grief is so deep because the heart is so pure.

Here is the God I want to believe in: a Father who, from the beginning of creation, has stretched out his arms in merciful blessing, never forcing himself on anyone, but always waiting; never letting his arms drop down in despair, but always hoping that his children will return so that he can speak words of love to them and let his tired arms rest on their shoulders. His only desire is to bless.

The true center of Rembrandt’s painting is the hands of the father. On them all the light is concentrated; on them the eyes of the bystanders are focused; in them mercy becomes flesh; upon them forgiveness, reconciliation, and healing come together, and, through them, not only the tired son, but also the worn-out father find their rest.

During his sixty-three years, Rembrandt saw not only his dear wife Saskia die, but also three sons, two daughters, and the two women with whom he lived. The grief for his beloved son Titus, who died at the age of twenty-six shortly after his marriage, has never been described, but in the father of the Prodigal Son we can see how many tears it must have cost him.

The father’s left hand touching the son’s shoulder is strong and muscular. The fingers are spread out and cover a large part of the prodigal son’s shoulder and back. I can see a certain pressure, especially in the thumb. That hand seems not only to touch, but, with its strength, also to hold. Even though there is a gentleness in the way the father’s left hand touches his son, it is not without a firm grip. How different is the father’s right hand! This hand does not hold or grasp. It is refined, soft, and very tender. The fingers are close to each other and they have an elegant quality. It

...more

The Father is not simply a great patriarch. He is mother as well as father. He touches the son with a masculine hand and a feminine hand. He holds, and she caresses. He confirms and she consoles. He is, indeed, God, in whom both manhood and womanhood, fatherhood and motherhood, are fully present. That

My friend Richard White pointed out to me that the caressing feminine hand of the father parallels the bare, wounded foot of the son, while the strong masculine hand parallels the foot dressed in a sandal. Is it too much to think that the one hand protects the vulnerable side of the son, while the other hand reinforces the son’s strength and desire to get on with his life?