More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

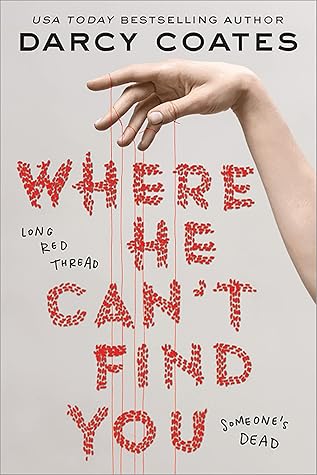

She couldn’t see them, but she knew what color they were. Red. It was always red threads.

It couldn’t see well, but it could hear and smell.

The nightmares were always the first warning. They came before any of the other signs—before the birds that plunged out of the sky, before the streetlights all died, before the sickness. Before the disappearances.

Now, she had nearly two thousand subscribers. She’d started to get small sponsorship deals. But those five original followers were still there, still cheering her on with each new video, and she always replied to thank them. Abby hadn’t told Hope that the accounts were hers. She probably never would.

Abby couldn’t blame him. Not after what the Stitcher did to his parents.

When people wanted to say something nice about Doubtful, Illinois, they called it a bike-friendly town. What that really meant was that cars were too unreliable. Most of the time they’d work as intended. But sometimes, with no warning, they would stall. Or grind to a halt. Or simply refuse to start.

Things in Doubtful just broke easily.

Abby remembered how, when she was young and eager to have adventures, she’d wanted to explore some of those empty buildings. She’d quickly learned why that was a bad idea. It wasn’t unheard of to find things in them.

This was how you survived in Doubtful. You watched. You learned. And you figured out the rules that would keep you safe.

The shape on the stretcher was covered by a white sheet. It wasn’t large enough to be a whole human. But it was undeniably part of one.

Abby’s heart squeezed painfully. Charles Vickers stood almost directly below their hiding place. He tilted his head, angling his gaze up toward them. And sent them one of those small, knowing smirks. They all drew back. Abby’s shoulder pressed against the concrete half wall. Riya’s breath was hot and shallow on the back of her neck. Charles Vickers’s smile widened a fraction, showing just a sliver of small, immaculate teeth. Then he turned and continued walking along the sidewalk, disappearing deeper into the town.

“Stitcher.” Riya spat the word like it was a curse. “More bodies, and the police just let him go. Again.”

And it was always better to be on the approaching side of daylight, not the receding.

something about the town just felt deeply, thoroughly wrong.

It was the last present she’d gotten from her father. One of the last nice memories she’d had of him, before he’d tried to challenge Charles Vickers. Just like too many things in her life, it had become a bittersweet staple. Each day she saw the box, it hurt something inside of her. But giving it up would have hurt more.

“I accidentally made too much. Help me out.” He glanced at the sandwich, then at her. “We both know you didn’t.”

Rhys wasn’t dangerous. No—Abby had to correct herself. He was rarely dangerous.

She’d only seen him lash out once: when Sam Gunner had hit her across the face with a hockey stick, splitting her lip. There’d been blood. Not just on Abby’s mouth, but on Sam’s face and Rhys’s hands, as well.

“They found her body last night.” Connor, always happy to talk, laid the final slice of bread onto his sandwich and examined the result with a critical eye. “Her, and part of someone else.”

“Who’s Charles Vickers?” “He’s the Stitcher,” Connor said. “He’s the last thing you’ll ever see before you die.”

“I love your everything might just be the boldest pickup line I’ve ever heard.”

She’d been cut up and spliced back together with a second victim, identity unknown. The red thread stitching pieces of her skin into place matched the material left inside her purse.

“Abs,” she called. “I’m making a video. Can I borrow your blue top?” Abby slung her backpack onto the living room chair and stretched. “The one with the lace? Sure.” “Thank you!” Hope appeared at the top of the stairs, beaming. She was already wearing the lacy blue top, and Abby had to laugh.

He was getting older. It was only something she’d started to notice in the last year, but now she couldn’t stop seeing the gradual changes.

There’s a sad yet quieting fear about realizing your parents have begun to show the signs of aging . It makes it more all more real that someday they won’t be around .

“That body we retrieved this morning? That was worse than just about anything I’ve had to deal with before. It was…it was like something out of a nightmare. And, once we got back to the station, no one wanted to talk about it.” Just like how no one at school seemed to want to look at the missing posters.

It wasn’t as though getting indoors before dusk was enough to keep someone safe. People were still taken during daylight, including January Spalling.

Nearly two-thirds of all victims were taken between nightfall and dawn.

As he turned, she caught a flash of the box he held under one arm. Inside were dozens upon dozens of spools of vivid red thread.

It was common knowledge that Charles Vickers placed special orders at the store for cases of red thread that matched the shade and thickness of the stitches in the bodies. He’d order a new box two or three times a year, she’d been told. It was the first time Abby had seen the purchase with her own eyes, though.

It was at the lakeside where they’d first started calling themselves the Jackrabbits. Because a jackrabbit never drops its guard, Rhys had said. A jackrabbit runs, and it runs fast, and it survives.

their mother…the grief had hit her in unending waves. She’d been different ever since. It had put her into this spiral, where she slowly slipped further from them, day after day.

But she hadn’t realized that her silence might be hurting her sister in a completely different way. We didn’t forget him. But we pretended we did.

Doubtful, Illinois, was a glue trap. People sometimes came in, but they very rarely left.

“His body hasn’t been found yet. That’s why his car is still there. There’s this kind of rule in Doubtful…when someone goes missing, you leave their stuff where it is.”

“Every time a body is found, a small list of suspects are interviewed. Every time, those suspects are let go.” “How long’s the list?” “Now? One name,” Abby said. She drew a deep breath and let it out in a sigh. “Charles Vickers.”

“The Stitcher doesn’t just kill his victims,” Abby said. “He keeps their bodies. Sometimes for a long time. He’ll dissect them and sew them back together in unnatural ways.

They were wildly different people—different body builds, different facial shapes, different personalities. But, with the exception of Hope, they all had the same look around their eyes. Haunted. Tense. Like prey animals that had spent their entire lives trying to outrun a tireless predator.

The town survived on the mining jobs. It was almost everyone’s livelihood, and it was snatched away with no warning. It might have been enough to cause someone with a volatile temperament to, well, snap. The killings might have originally been in revenge.

“A portion of the town believes the Stitcher is a monster,” Abby said. “Something evil and ancient that was woken inside the mines. Another portion believes the Stitcher is a man, and that he lives inside our town. A final portion—the larger portion—tries not to think about it at all. You ask them about the Stitcher, and they’ll change the subject as quickly as they can.”

It’s human nature. We want to feel that we have control over our destiny, that we wouldn’t ever make the same mistakes that cost someone else everything.

When I lifted my head again, the man was gone. But something red ran down the windows. Streaks of blood being washed away by the rain.

Not many people drive through Doubtful, and almost no one leaves their home after dusk. If you hear multiple cars at night, it’s almost certain that it’s the police.

I’d been right. The police had found my parents. Their remains had been left in a small clearing. Their skin had been removed from their bodies in pieces and stitched together like a patchwork. Everything else—bones, organs, hair, and teeth—had been piled inside the cloth made of their skin, and then sewn up into a bulging, wet parcel. It was suspended about fifteen feet above the ground. Yards of red thread looped around it and held it in place, tying it to the surrounding trees. Disassembled and sewn back together like that, they no longer looked like my father and my mother.

“Sometimes people leave…offerings. Gifts to gain favor with the Stitcher. They think if they can, I dunno, appease him, he’ll leave them alone.”

“There are no other suspects. If we’re wrong, it can only mean the Stitcher isn’t human at all. That the legend is true. That the Stitcher is some monster. And if that’s true… I don’t think that’s a world I know how to live in.”