More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“He’s coming,” she whispered, and her voice sounded like the rattle of dry insect wings. “He’s coming. We need to hide you where he can’t find you.”

Life in his house was chaotic, but they had a few concrete rules that no one—not even the youngest—dared break. Their house had four doors leading outside, and all of them had to stay locked at all times.

They were all careful with it, but his mother was the most paranoid. He couldn’t believe she’d seen the door was open and had not done anything about it. No. His hand was still outstretched toward the handle. Cold air raised gooseflesh across his arms. Their house was crammed full of people, but suddenly felt very empty. She wouldn’t. The first thing she’d have done was lock the door. No question about it. And yet, it was open again.

People always said sunsets were beautiful. To Connor, it looked more like a massive bruise swelling out across the horizon.

She’d already seen three body bags carried out, and they still weren’t done.

“Who was that in there with you?” her mother asked. Riya, who was pulling her seatbelt down toward the buckle, went still. “What?” “There was someone behind you.” Her mother turned toward her, and her pupils seemed tiny in her wide eyes. “It’s why I put my lights on. Because someone was behind you, and they were walking closer, and I couldn’t see who it was.” They both stared into Bobby’s Pizzeria. The dining room was empty.

First, complex technology fails. The cars and smartphones and computers. Then the less complicated machines; streetlights, radios. The simple machines, though…the clocks, the doorbells, the house lights… When they go, it’s as bad as it can get.

She took her hand away and saw smears of glistening blood. Drops of it trailed over the sill and down the wall toward the bed. It was fresh. It shouldn’t have been possible, but the patch she’d touched had felt warm. Hope was here just seconds ago. Something woke me, and it wasn’t the nightmare. I heard her being taken.

“Abby.” Rhys glanced at her, and he seemed to communicate worlds within that one look. “I won’t be leaving your side tonight.” Her heart was in her throat. He dipped his head toward her, his eyes intense as they searched hers. “Whatever you’re planning to do, I’ll be with you.

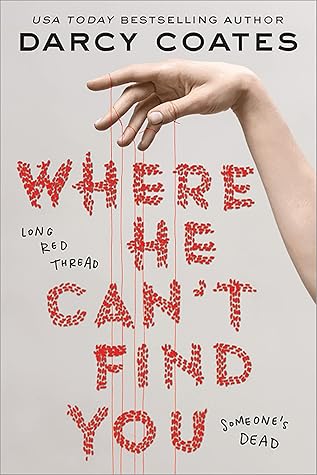

Portraits had been hung on the wall; she was so focused on the path ahead that she was halfway up the stairs before she realized the portraits were missing person posters, taken from around town and lovingly framed, each one suspended by a length of red thread.

For a second, there was nothing but silence. Then a horrible, sick sound rose from the floor below. Not quite a cough, not quite a gasp, but thin and raspy and delighted. Charles Vickers was laughing.

Hope wasn’t here. Rhys was alone, downstairs, with the Stitcher, and the Stitcher was laughing. And both Rhys and Abby were now trapped in a house with bars over its windows and padlocks on its doors: as impossible to escape from as it was to get into.

“But you didn’t ask, did you?” The singsong quality was devolving into something colder and angrier, full of grit and ice. “And now you need to face the consequences.”

A game of hide-and-seek in a monster’s house.

“You were very lucky tonight,” she said, and there was an undercurrent of dual meaning to the words.

She’s not there. That’s why Vickers let us go. And why he called the police. Because he doesn’t stitch people at his house.” She stood up, her heart running fast. “I was never going to find Hope there. And he knew it.”

And she remembered the cutting board, covered with five sharp knives. It was a red herring. She’d picked up one of the knives to defend herself with and had felt dust on the handle. Those knives had been displayed on his kitchen counter for a long, long time. Waiting…to be found?

While Riya’s bedroom was filled with sports trophies and memorabilia, and Connor’s was decorated with posters from the shows and movies he liked, Rhys’s bedroom was bare.

“You’re staying for Alma, aren’t you?” He glanced at her quickly. “Yes.” A pause, then he added, so quietly that she almost didn’t hear, “And for other things.” Her heart did the strange flopping motion it something did around him, but there was no bittersweetness about it this time. Just aching, grinding pain.

The Stitcher’s victims didn’t always die immediately. Sometimes he kept them alive for a while. Sometimes small body parts were found around town weeks before their official deaths.

“So sad. He takes so many. And only one of them ever came back.” Abby froze at the door. Slowly, she turned toward Alma, who stood at the window and stared out into the morning light. “Did you say…” Her voice caught. Every hair rose as gooseflesh covered her. “Someone came back?”

“You’re not lying to me, are you?” “I wouldn’t. Not about this.” “Oh.” Hope was taken. That thought had seemed like a curiosity before, but now it hit her like a sledgehammer.

“This town…” Riya seemed to be struggling to put her thoughts into words. “It’s like it plants hooks in you. And the longer you live here, the more hooks start to embed themselves, and if you try to pull free you’ll only hurt yourself. If people are taken away from the town—if they’re forced to leave their homes when they’re not ready—they don’t usually make it. Most patients who are transported to hospitals or care facilities don’t live past six months.”

“You talk about the Stitcher like he’s some all-powerful supernatural entity, but in the next breath you try to tell me he’s just some guy who lives nearby. It doesn’t make sense.”

She’d heard that drowning people would clutch at anyone trying to rescue them, and very often pull them under as well. Right now, Abby was drowning. And Riya could feel herself teetering on the edge of it, too: wanting to grasp at anyone who could help, but knowing she’d just be spreading the damage.

lot of people didn’t want to be around someone who’d come so close to the Stitcher. As though it tainted them by proximity. As though being too near them might draw the Stitcher’s attention, somehow.

There’s no curse. Leaving those offerings won’t save you, and living with those who have been touched won’t harm you. When the Stitcher decides to take someone, it’s all empty, hopeless luck.”

People say I’m lucky that I came back. That I was blessed, that I had a guardian angel watching over me. I think I’d consider myself luckier if I’d never been taken at all.

In darkness that intense, you lose the ability to tell time, to judge distance, or to even know where your arms and legs are in relation to one another. It’s oppressive in a way that breaks spirits and crushes hope.

If it had ever known how to speak, it had forgotten by that point. All it knew was the darkness, and the threads.

I survived the Stitcher not through cunning or preparedness, but through pure chance. Later, when I learned how expansive the mines truly are, I realized how unlikely my escape had actually been. Across countless scores of victims, I was the only one who’d managed to find an exit.

I heard he’d been let go from his job a few years after my rescue. Isn’t that a polite way of putting it? Let go? As though they’d been clinging to him and finally lost the strength to hold on any longer. They probably thought they were letting go of a problem, but I suspect the station felt his loss.

If the mines truly still existed beneath them, and they were being used by the Stitcher, it would answer so many questions. Like how Vickers was able to contain multiple victims at a time. How no one had ever heard them calling for help. And how no location for where the bodies had been butchered and sewn up could ever be pinpointed. The mines were the ideal location for Vickers to hide his crimes. They’d been under Abby’s feet this entire time, and she hadn’t even known.

“You said the Stitcher came for you twice while you were inside the mines, but you survived both times. What does that mean?” For a moment, Bridgette was silent, her dark eyes inscrutable. Then, slowly, she reached for the blanket draped across her lap. Her long fingers curled into the fabric as she pulled it up. The space underneath was empty. Her legs had been carved away, one at a time, above the knees.

Vickers screamed. It was brutal, furious, animalistic. His attacks on the tree intensified. Connor had a horrible sense that Vickers was picturing a face there, instead of the foliage he was shredding.

Rhys continued to work next to her. Abby glanced at him. His expression was unreadable, but she knew him well enough to understand what he was thinking. The realization came with a crushing amount of grief. He was doing this for her sake. And he was going to dig for as long as Abby wanted them to. Even though he knew. They were never going to get through.

“We shouldn’t be splitting up. Bridgette said the Stitcher wasn’t done yet.” “We left Connor on his own,” Rhys noted. “And he’s watching the house. We’ll have warning if Vickers tries to leave,” Abby said.

But what if it's not him? or if he has an entry point hidden in his house so no one would see him leave ?

She didn’t try to shut the window. Part of her wished the Stitcher would come back and take her, too.

Just lied my butt off to your parents about you being in the bathroom. Whichever guy you’re with, he’d better be damn cute. “Not sure if Charles Vickers hits anyone’s definition of cute,” Connor said, “but sure.”

Behind her, their yard looked like a forest. Trees and bushes and coiling vines overlapped. And in between them, just visible behind Hope’s shoulder, was a man. A man, in their house’s backyard, watching Hope as she danced.

Abby had remembered how Jessica had been missing from school for a week and how people had murmured that her uncle, who was living with her family, had gone missing during the night. Then Abby had stared up at the mangled body suspended from the rafters by endless lines of red thread and she’d wanted to scream.

Abby opened her mouth, then closed it again. Fear and shock and grief stung her eyes as she blinked. The bodies were all old and desiccated. Dry skin threatened to tear around the stitches. She’d found the Price family, she was fairly sure.