More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

His last speech on the African continent was also his swan song as a public figure or, as it is sometimes discreetly referred to in Cuba,...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

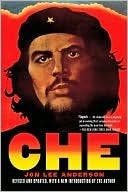

During his trip abroad in 1964, Che met with the Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, a leading “anti-imperialist.” Anwar al-Sadat is next to Che.

He had written a note to Fidel that was at once a farewell letter, a waiver of any responsibility the Cuban government might be perceived as having for his actions, and a last will and testament:

I am not sorry that I leave nothing material to my wife and children. I am happy it is that way. I ask nothing for them, as the state will provide them with enough to live on and to have an education. ...

Hasta la victoria siempre! Patria o muerte! I embrace you with all my revolutionary fervor. Che.

Che had also left a letter to be forwarded to his par...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Nothing essential has changed, except that I am more conscious, my Marxism is deeper and more crystallized. I believe in the armed struggle as the only solution for the peoples who fight to free themselves and I am consistent with my beliefs.

It could be that this will be the definitive one. I don’t go looking for it, but it is within the logical calculations of probabilities. If it is to be, then this is my final embrace.

I have loved you very much, only I have not known how to show my love. I am extremely rigid in my actions and I believe that at times you did not understand me. On the other hand, it was not easy to understand me.

A great hug from a prodigal son, recalcitrant for you.

And to his five children, in a letter to be read to them only after his death, he wrote:

If one day you must read this letter, it will be because I am no longer among you. You will almost not remember me and the littlest ones will remember nothing at all. Your father has been a man who acted according to his beliefs and certainly has been faithful to his convictions.

that each one of us, on our own, is worthless.

Above all, try always to be able to feel deeply any injustice committed against any person in any part of the world.

President Johnson, who had defeated Goldwater in the election in November, had dispatched U.S. marines to quash an armed leftist uprising there. It was the first American military invasion in the Western Hemisphere in decades,

Do my letters sound strange to you? I don’t know if we have lost the naturalness with which we used to speak to each other, or if we never had it and have always spoken with that slightly ironic tone used by those of us from the shores of the [Río de la] Plata, exaggerated by our own private family code. ...

At Celia’s funeral service, Che’s framed photograph sat prominently on the coffin. María Elena said that she felt sorry for Celia’s other children: “It was as if they weren’t there. It was as if she had only one child—Che.” And

Che found the Congolese lazy. During marches, they carried nothing except their personal weapons, cartridges, and blankets, and if asked to help carry an extra load, whether food or some other item, they would refuse, saying, “Mimi hapana Motocar” (“I am not a truck”). As time wore on, they began saying, “Mimi hapana Cuban” (“I am not a Cuban”).

Che was forced to stay behind; in late June a column of forty Cubans and 160 Congolese and Rwandan Tutsi set out for Bendera.

The attack, which begun on July 29, was a catastrophe. The assault leader, Víctor Dreke, reported that at the first outbreak of combat, many of the Tutsi fled, abandoning their weapons, while many of the Congolese simply refused to fight at all. Over a third of the men had deserted before the fighting even began.

Four Cubans were killed, and one of their diaries fell into enemy hands, which meant that the mercenaries and the CIA—which had sent anti-Castro Cuban exiles to fly bombing and reconnaissance missions for the government for...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Pombo said that when they got to shore, Che turned to his three young companions and said, “Well, we carry on. Are you ready to continue?” They understood then that Che was not going back to Cuba. “Where?” Pombo asked. And Che replied, “Wherever.”

“He could not return to Cuba without having achieved success,” Pombo explained. “He thought that the best thing was to continue. Through his own efforts, with whatever possibilities, he had to continue the struggle.” Che had planned to be fighting for five years, but after only six months it was all over.

The title he chose, “Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria (Congo),” echoed the title of his book on the Cuban revolutionary war and made the point that the Congo was just one more stage in a historic struggle that had as its final goal the liberation of the world’s oppressed.

There was a marked difference between the two accounts.

Che made clear in his opening pages when he wrote, “This is the story of a failure.”

At the end of the book, he listed his own faults. “For a long time I maintained an attitude that could be described as excessively complacent,” he said, “and at other times, perhaps due to an innate characteristic of mine, I exploded in ways that were very cutting and very hurtful to others.”

I have come out with more faith than ever in the guerrilla struggle, but we have failed. My responsibility is great; I will not forget the defeat, nor its most precious lessons.

The Congo experience had distanced them. They were still friends, but they no longer believed in the same things. Fernández Mell had done a lot of thinking about Che’s notions of continental guerrilla war and had begun to doubt the wisdom of the strategy, at least for Africa.

He thought Che was stubbornly deluded about it. “In the Congo, Che had said things to us that I am convinced he knew weren’t realistic,” Fernández Mell explained, “although he wasn’t a man who said things he didn’t feel. ... He had it stuck deeply in his head that he had found the path to liberate the people and that it would be successful, and he expounded it as an absolute truth. So he could not accept that the attempt in the Congo ruined that strategy he had thought out so well.”

This is perhaps the most crucial single question about the life of Ernesto Che Guevara that still remains unsatisfactorily answered: who decided he should go to Bolivia; and when and why was that decision made?

Fidel always said that Che selected Bolivia himself, and that he had tried to stall him, urging him to wait until conditions were more “advanced.” Manuel Piñeiro concurred.

After one of Aleida’s clandestine reunions with Che abroad, she had returned with a special present for Borrego. It was Che’s own heavily marked-up copy of the Soviet Manual of Political Economy that he had begun working on in Dar es Salaam.

Accompanying Che’s copy was a ream of notations and comments, many of them highly critical, in which he questioned some of the basic tenets of scientific socialism as codified by the Soviet Union.

He indicted Lenin—who had introduced some capitalist forms of competition into the Soviet Union as a means of kick-starting its economy in the 1920s—as the “culprit” in many of the Soviet Union’s mistakes, and, while reiterating his admiration for and respect toward the culprit, he warned, in block letters, that the U.S.S.R. and Soviet bloc were doomed to “return to capitalism.”

When Borrego read this, he was stunned. “Che is really audacious,” he thought to himself. “This writing is heretical!” He thought Che had gone too far. With the passage of time, of course, Che would be proved right.

In his notes, Che softened the criticism of Lenin by pointing out that his errors did not make him an “enemy,” and that Che’s own criticisms were “intended within the spirit of Marxist revolutionary criticism,” in order to “modernize Marxism” and to correct its “mistaken p...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Regarding a passage that read, “Socialism need not come about through violence, as proven by the socialist states of Eastern Europe, where change came through peaceful means,” he quipped, “What was the Soviet army doing, scratching its balls?”

Borrego even accompanied Che to a session with the “physiognomy specialist” from Cuban intelligence who plucked out the hairs on top of Che’s head one by one in order to give him the severely receding hairline of a man in his mid-fifties.

When Che was in his full disguise, Fidel introduced him to a few of the highest-ranking ministers of Cuba as a visiting foreign friend and nobody, according to Fidel, recognized him. “It was really perfect,” Fidel recalled later.

A special feast had been prepared, and everyone sat at a long picnic table. When Borrego got up, intending to get a second helping of the ice cream, Che called after him in a loud voice, “Hey, Borrego! You’re not going to Bolivia, so why should you have seconds? Why don’t you let the men who are going eat it?”

Che’s criticism, heard by everyone, lacerated Borrego; tears began running down his cheeks. Without saying a word, he walked away, burning with shame and indignation. He sat on a log listening to the rough-and-ready guerrillas titter and break into guffaws behind his back. After a few minutes, he heard steps. A hand was placed softly on his head and tousled his hair. “I’m sorry for what I said,” Che whispered. “Come on, it’s not such a big thing. Come back.” Without looking up, Borrego said, “Fuck off,” and stayed where he was for a long time. “It was the worst thing Che ever did to me,”

...more

Che and Fidel met in a quick, short embrace, then stood back looking at each other intently, their arms outstretched on each other’s shoulders, for a long moment. Fidel later described his good-bye with Che as a manly abrazo befitting two old comrades in arms. Since both were reserved men when it came to public displays of emotion, their hug, he said, had not been very effusive. But Benigno remembered it as a deeply charged moment.

Then Che got into his car, told the driver: “Drive, damnit!” and was gone. Afterward, said Benigno, a melancholy silence fell over the camp. Fidel walked away from the men and sat by himself. He was seen to drop his head and stay that way for a long time. The men wondered if he was weeping, but no one dared approach him.

Bolivia must be sacrificed so that the revolutions in the neighboring countries may begin. CHE

Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome. CHE

In his postmortem of the Congo fiasco, Che acknowledged that one of his greatest mistakes was to have attempted a chantaje de cuerpo presente, blackmail by physical presence. He had foisted himself unannounced on the Congolese rebels, causing animosity and suspicion among the leadership. It was one of the mistakes he had vowed to learn from. Yet when he went to Bolivia in early November 1966, he neatly replicated his Congo chantaje, once again appearing on alien turf without an invitation, convinced that the Bolivian Communist Party leaders wouldn’t back out of the impending guerrilla war once

...more

Even before Che had arrived, in fact, his advance men had learned that Ciro Algarañaz, their only immediate neighbor, was spreading the word that he suspected the newcomers were cocaine traffickers, a budding profession in this coca-producing nation.

Che foresaw an astonishing, even fantastic sequence of events.

“Bolivia must be sacrificed so that the revolutions in the neighboring countries may begin,” he said.