More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Che discovered Aleida fixing decorative lamps. She explained that she had taken them from their previous home, and he blew up and ordered her to take them back. When one of the children was sick, Aleida asked to be allowed to take the child to the hospital in Che’s car. He refused, telling her to take the bus like everybody else. The gas in the car belonged to “the people” and was intended for use in his public duties, not for personal reasons.

When food rationing began, and one of his colleagues complained, Che said that his own family was eating fine on what the government allowed. The colleague pointed out that Che had a special food supplement. Che investigated, found that this was true, and had the benefit eliminated. His family would receive no special favors.

Rumors circulated about how the Guevaras often didn’t have enough to eat, and that Aleida had to borrow money from ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Che’s relationship with Aleida was a source of curiosity to many. He was an intellectual, a scholar, and an assiduous reader of books. Aleida preferred movies and social gatherings. He was austere and shunned the good things in life. Aleida, like most people, appreciated them, and aspired to possess some of the comforts enjoyed by most comandantes’ wives—even in revolutionary Cuba.

Once, while he was visiting his mother-in-law’s house in Santa Clara, she asked him if he wanted a bath. “Not if Aleida’s not in it,” he quipped.

Che regarded his father warmly but thought he was immature. (Aleida never had much time for Ernesto senior and acknowledged that after Che’s death, they had a public falling-out when she heard him tell a gathering that he was responsible for inculcating Che’s early socialist leanings. She challenged him, telling him it was a lie,

As much as Che loved his mother, she had never been a physically demonstrative woman. Just as in his adolescence he had gone to his aunt Beatriz for some maternal attention, he sought it as a grown man from Aleida. She recognized this need and responded by mothering him, dressing him, and even bathing him.

In a country where many of the men had second and even third “wives” simultaneously with their first marriage, sired children with several women, and had affairs quite openly, Che was, by all accounts, steadfastly monogamous in Cuba, despite the fact that woman flocked to him like groupies to a pop star. One of his aides was at a social gathering where a pretty young woman blatantly flirted with Che. Instead of being flatttered and responding with gallantry or banter, Che primly scolded the woman, telling her to behave herself.

A friend recalled being with him at a dinner in a foreign embassy. They had been seated with the ambassador’s daughter, and it was implied that the young woman was available to Che. The daughter, said Che’s friend, was so beautiful that any man would have forgotten his marriage vows or any commitment to the revolution just to sleep with her. Che was finding it difficult to resist. He finally turned to his companion and whispered, “Find an excuse to get me out of here before I succumb. I can’t bear any more.”

Adolfo Rotblat was a Jewish boy of twenty from Buenos Aires whom they called Pupi. He suffered from asthma and began lagging behind on the marches, complaining about the harshness of guerrilla life. It was obvious he wasn’t cut out for it, but instead of letting him leave, Masetti dragged him along. With every day that passed, Pupi’s physical and mental state deteriorated. Soon he was completely broken.

When he rejoined the guerrillas in October for a few weeks, Bustos found Pupi in a pathetic condition. He lived in a state of terror, wept, fell behind in the marches, and slowed everyone down.

A few days later, Masetti told Bustos, “Look, this situation is becoming unbearable. No one can stand it anymore. Nobody wants to carry him, and so a measure has to be taken that sanitizes the group’s psychology, that liberates it from this thing that is corroding it.” Masetti had decided to shoot him.

Che may have been the original architect of the Soviet-Cuban relationship, but his call to armed struggle, his emphasis on rural guerrilla warfare, and his stubborn determination to train, arm, and fund Communist Party dissidents—even Trotskyites—over the protests of their national organizations had led to a growing suspicion in Moscow that he was playing Mao’s game.

A KGB agent, Oleg Darushenkov, had been assigned to stay close to Che since late 1962.

Many in the Kremlin, especially after the missile crisis, feared that Cuba’s escalating support for guerrilla “adventures,” which everyone knew was being spearheaded by Che, might drag the Soviet Union into a new confrontation with the United States.

Burlatsky said the view that Che was a dangerous character took on added weight because of his remarks after the missile crisis, when he told the Soviets that they should have used their missiles. It was a sentiment that Fidel had also expressed privately, but Che had said so publicly—and whereas Fidel soon modified his rhetoric, few doubted that Che meant what he said.

Nikolai Metutsov,

Metutsov traveled to Cuba at the end of 1963 in a Soviet delegation led by Nikolai Podgorny, president of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. When he spoke about his mission many years later, he made it clear that neither Fidel nor Raúl was really the issue.

“We knew about the process by which they had come to Marxism, how sincere their comprehension of Marxism was. ... We knew that in essence Fidel was a liberal bourgeois democrat, and we knew that his brother Raúl was closer to the Communists and was in the Party. Now, about Che Guevara: he seemed to me to be the most prepared theoretically of all the political leadership.”

As he spoke, trying to reassure the younger man, Metutsov said he began to experience a strange sensation. A jowly, beetle-browed man with huge ears and pale blue eyes, Metutsov found himself “falling in love” with Che.

“I told him: ‘You know, I’m a little older than you, but I like you, I like above all your looks.’ And I confessed, I confessed my love for him because he was a very attractive young man. ... I knew his defects, from all the papers, all the information we had, but when I was talking to him, when we dealt with one another, we joked, we laughed, and we talked about less than serious things, and I forgot about his defects. ... I felt attracted to him, do you understand?

It was as if I wanted to get away, to separate myself, but he attracted me, you see. ... He had very beautiful eyes. Magnificent eyes, so deep, so generous, so honest, a stare that was so honest that somehow, one could not help but feel it ... and he spoke very well, he became inwardly excited, and his spe...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“Externally one could truly say that, yes, Che Guevara was contaminated by Maoism because of his Maoist slogan that the rifle can create the power. And certainly he can be considered a Trotskyite because he went to Latin America to stimulate the revolutionary movement ... but in any case I think these are external signs, superficial ones, and that deep down, what was most profound in him was his aspiration to help man on the basis of Marxism-Leninism.”

“Pancho went to Cuba to see Che, carrying our critical views, that we thought the rural guerrilla thing wouldn’t work tactically,” Schmucler recalled. “But when he got there, he couldn’t open his mouth. Che talked for two or three hours, and Pancho didn’t say anything.” Afterward, Aricó told his friends that once he was sitting in front of Che, he was overcome by the force of Che’s presence and arguments and was too intimidated to contradict anything. “It was Che,” he said.

the men had starved to death. Bustos tried to explain the conditions of the jungle around Orán, an area with virtually no peasants and no food; the difficulties of hunting, how at one point the guerrillas had shot a tapir but found it impossible to eat because the meat simply decomposed. “When I told him that, Che said no, they should have boiled it longer, so that the acids converted or something, and then it would have been fine.”

He had begun his speech by quoting from a poem by the Spaniard León Felipe, describing the tragedy of human toil. “No one has been able to dig the rhythm of the sun, ... no one has yet cut an ear of corn with love and grace”:

Today in our Cuba, everyday work takes on new meaning. It is done with new happiness.

And we could invite him to our cane fields so that he might see our women cut the cane with love and grace, so that he might see the virile strength of our workers, cutting the cane with love, so that he might see a new attitude toward work, so that he might see that what enslaves man is not work but rather his failure to possess the means of production.

man once again regains the old sense of happiness in work, the happiness of fulfilling a duty,

He becomes happy to feel himself a cog in the wheel, a cog that has its own characteristics and is necessary, though not indispensable, to the production process, a conscious cog, a cog that has its own motor, and that consciously tries to push itself harder and harder to carry to a happy conclusion one of the premises of the construction of socialism—creating a sufficient quantity of consumer goods for the entire population.

Che’s habit of referring to the people, the workers, as bits of machinery affords a glimpse of his emotional distance from individual reality. He had the coldly analytical mind of a medical researcher and a chess player. The terms he employed for individuals were reductive, while the value of their labor in the social context was idealized, rendered lyrically.

The Communist consciousness he had attained was an elusive, abstract, and even unwanted state of being for many people,

His mother once told the Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano that from the time of his asthmatic childhood, her son “had always lived trying to prove to himself that he could do everything he couldn’t do, and in that way he had polished his amazing willpower.”

“Thus,” Galeano wrote, “he had become the most puritanical of the Western revolutionary leaders.

The attacks by the CIA-backed Cuban exiles had also intensified. Hijackings, sabotage, and armed commando raids against Cuban shipping were now taking place with alarming frequency.

On September 24, a seaborne CIA action team based in Nicaragua attacked the Spanish freighter Sierra de Aránzazu as it sailed toward Cuba with a cargo of industrial equipment. The Spanish captain and two crew members were killed in the raid, and the ship was set ablaze and disabled.

The agent back at the base who had authorized the attack was Felix Rodríguez.

Che was already in the process of extracting himself from Cuba’s revolutionary government. He had told Fidel he wanted to leave. The trip to Moscow had convinced him that Soviet pressure on Cuba to accept the Kremlin’s socialist model was overwhelming.

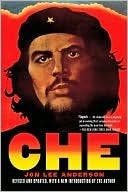

Che took pains to groom himself for his appearance before the Nineteenth UN General Assembly on December 11, 1964. His boots were polished, his olive green uniform was pressed, and his hair and beard were neatly combed. Nevertheless, he presented a striking contrast to the conservatively attired diplomats who filled the hall, and his defiant speech did not disappoint those who had anticipated a harangue worthy of the famous apostle of revolutionary socialism.

He then proceeded to link the “white imperialist” action in the Congo with western indifference to the apartheid regime in South Africa and the racial inequalities in the United States.

“How can the country that murders its own children and discriminates between them daily because of the color of their skins, a country that allows the murderers of Negroes to go free, actually protects them and punishes the Negroes for demanding respect for their lawful rights as free human beings, claim to be a guardian of liberty?”

Che addressing the United Nations, Dece...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Not surprisingly, Che’s words provoked vigorous denunciations by the U.S. ambassador, Adlai Stevenson; and by some of the Latin envoys present. Outside the UN building, Cuban exiles angrily protested against his appearance.

Some went considerably farther. Several gusanos were arrested after firing bazookas at the UN building from across the East River, and a woman was prevented from trying to stab Che with a knife.

To the shouted insults of the gusano protestors, he raised his hand in a universally understood gesture meaning “Fuck you.”

Not everyone was displeased with Che’s presence. Malcolm

Just before Babu appeared onstage, Malcolm X read a message from Che. “I love a revolutionary,” he said. “And one of the most revolutionary men in this country right now was going to come out here with our friend Sheikh Babu, but he thought better of it. But he did send this message. It says: ‘Dear brothers and sisters of Harlem. I would have liked to have been with you and Brother Babu, but the actual conditions are not good for this meeting.* Receive the warm salutations of the Cuban people and especially those of Fidel, who remembers enthusiastically his visit to Harlem a few years ago.

...more

This is from Che Guevara. I’m happy to hear your warm round of applause in return because it lets the [white] man know that he’s just not in a position to tell us who we should applaud for and who we shouldn’t applaud for. And you don’t see any anti-Castro Cubans around here—we eat them up.”*

Che revealed his plans for the Congo, but when he mentioned that he was thinking of leading the Cuban military expedition himself, Nasser told him that it would be a mistake to become directly involved in the conflict, that if he thought he could be like “Tarzan, a white man among blacks, leading and protecting them,” he was wrong. Nasser felt it was a proposition that could only end badly.

Despite such warnings, the poor reception his strategies had received in Dar es Salaam, his own doubts about the Congolese rebel leaders he had met, and his lack of hard information about the real situation inside the Congo, Che resolved to push ahead.