Five Questions for Candidates Who Want to Be Commander in Chief

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery)

War talk is cheap. But war is costly in both dollars and human lives.

The Reichstag in Berlin, pictured in June 1945. (Source: Imperial War Museum)

That’s why we should pose a set of questions to all of the presidential candidates, some of whom have recently –as the New York Times reported– proposed bombing oil fields in the Middle East (Donald Trump); sending 10,000 American troops to Iraq and Syria (Senator Lindsay Graham of South Carolina); and calling for a United States-led global coalition, including troops on the ground, to take out the Islamic State “with overwhelming force” (Jeb Bush). Hillary Clinton called for a Syrian no-fly zone in a speech made today (Nov. 19, 2015).

As the winds of war talk swirl about Paris, Syria, Iraq and the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), can the candidates for commander in chief please tell us clearly and specifically —

-As president, would you ask Congress for a declaration of war against the Islamic State?

-As president, would you commit American ground forces to capture and occupy territory in Iraq and Syria now held by the Islamic State?

-If so, how large should that force be and how long would that commitment last?

-Would you make such a commitment unilaterally—without international allies or partners?

-Would you ask the American people to make any sacrifice in undertaking this mission, such as raising taxes to pay for the war effort or reinstating the draft?

Let’s be clear. Under the Constitution, as commander in chief, the president has extraordinary prerogative to take military action without congressional involvement. In the 240 years since the American Revolution began, this country has seldom been free of some kind of military action at home or abroad. Yet American presidents have sent troops into the vast majority of these military conflicts without a formal declaration of war by Congress.

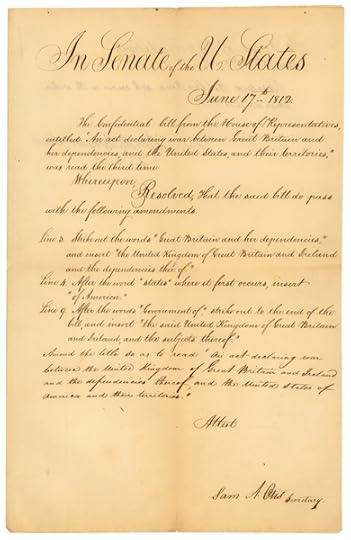

Declaration of the War of 1812 (Courtesy of National Archives)

In fact, in more than two centuries of military actions at home and around the globe, Congress has declared war only five times: against the United Kingdom of Great Britain in 1812, against Mexico, against Spain, and then in World War I and World War II. (Technically, there are eleven “official wars” as both World War I and World War II involved multiple declarations.)

Congressional resolutions authorizing action that are remarkably flexible –and often very expensive and long-lived—are probably not what the framers of the Constitution had in mind. On the other hand, they didn’t want standing professional armies either.

As commander in chief, many presidents have held and exercised almost unchecked power to commit U.S. troops to combat, often with a compliant Congress. From sending marines to fight the Barbary pirates to a decades-long, deadly struggle against the Seminoles of Florida, or chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico and far beyond, America has fought numerous “wars” without calling them that.

The Vietnam-era War Powers Act, enacted over Richard Nixon’s veto in 1973, attempted to correct what Congress and the American public saw as excessive war-making powers in the hands of the president. U.S. presidents have consistently taken the position that the War Powers Resolution is an unconstitutional infringement upon the power of the executive branch and its terms have rarely been invoked.

It has become far easier for Congress to stand back and stay uninvolved and comfortably ignorant. A vote in favor of a later unpopular decision, as Hillary Clinton learned of her Iraq vote in the Senate, can be an albatross.

And most of the American public has become increasingly disconnected from the sacrifices and costs of military life due to the volunteer nature of our armed services.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

Yet it is morally irresponsible to leave the fighting to a modern-day “warrior caste” of men and women in uniform, those who now volunteer, and then look the other way. We need to ask questions about the costs and consequences of both our leaders and candidates and hold them accountable, especially when we are talking about putting our uniformed men and woman in harm’s way.

After the American Revolution officially ended, Benjamin Franklin said,

“There never was a good war or a bad peace.”

Franklin was wrong. There are just wars and there are necessary wars –fought, as the preamble to the Constitution puts it, “For the common defense.”

Before we “let slip the dogs of war,” let’s hear the case made for that terrible decision in the clearest way. Let’s hear the answers to these questions.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.