At second hand

There's a minor coup on the back page of this week's TLS, for those of the book-collecting frame of mind. There our diarist J. C. reports on finding a dust-jacketed volume of Henry Miller's Plexus, the first publication of the celebrated Olympia Press in Paris, in Notting Hill's Book & Comic Exchange. This is not one of the 2,000 copies advertised for sale but a printer's copy, with his inscription and initials adorning the front free endpaper.

That's not bad going, I'd say, for ��5 in Book & Comic Exchange. Book collectors tend to save what excitement they can muster for association copies ��� principally books inscribed by their authors for other notable figures. Besides their (sometimes fairly arbitrary) market value, we are told, such inscriptions often have their own unique stories to tell. Do humbler, unassociated copies tell their own stories?

Such bibliographical tales take diverse forms, as is often revealed in the pages of the Book Collector or Henry Woudhuysen's TLS reports from the auction rooms. A copy of Eyeless in Gaza, as Professor Woudhuysen reported earlier this year, emerges from one sale catalogue as the object of a good roughing-up at the hands of the biographer Christopher Sykes, then Jean and Cyril Connolly: Jean has embellished it with a drawing of somebody being sick at the front; another sketch has God looking down despairingly on Huxley at work and exclaiming "O Dear! O Dear! O Dear!"

For a time, that copy belonged to one of the TLS's most distinguished bibliophile contributors, Anthony Hobson. What about more ordinary types and their more ordinary books? Well, J. C.'s Perambulatory Books series reveals one or two more he's picked up over years. Or there's the the writer and performer Nathan Penlington, who describes in The Boy in the Book how he bought 106 "Choose Your Own Adventure" novels on eBay and ended up tracking down their previous owner (out of whose teenage diary a tantalizing page had come with the set).

The journalist Josh Spero more recently carried out his own investigation into the subject. Spero's Second-hand Stories isn't so much about the books themselves as the lives of their previous owners ��� people who happened to apply to the same school (University College School in Hampstead) as Spero, or the same Oxford college (Magdalen). As a classicist by education, Spero intersperses episodes of autobiography with brief accounts of the previous owners of his classics books. The actor Sebastian Armesto turns out to be the former owner of North & Hillard's Latin Prose Composition, rather than his father, the historian and TLS contributor Felipe Fern��ndez-Armesto. The poet Peter Levi (one of the "great barely remembered literary figures of the last century", we're told) unwittingly bestowed on Spero a copy of Maurice Bowra's Odes of Pindar, which certainly qualifies as an association copy: it's inscribed "with love and gratitude" from the translator to the poet, who had helped him out with "many wise suggestions".

There's some enjoyable detective work in Spero's pages, although I take the point that some book owners' profiles are flatter than others ��� men are born equal, we're told (an interestingly tenacious untruth), but apparently they do not go on to live equally interesting lives. And not all books are so keen to reveal their owners' secrets, anyway.

Another small mystery, from Second-hand Stories: a copy of Corrado Ricci's Via Dell'Impero, co-written with Antonio Colini and Valerio Mariani, passes through the hands of Belinda Dennis, another classicist and a former president of the Association for Latin Teaching. The title itself is a clue to the book's age, as are the last letters on the title page, "A. XI E. F.", which constitute a particularly sinister way of describing the year 1933: Anno XI nell Et�� Fascista; the "eleventh year of the Fascist era", as Spero points out, "which began in 1922, when Mussolini became prime minister". The name of the road was later changed; what Spero cannot tell us is what Belinda Dennis (who died in 2003) made of it all.

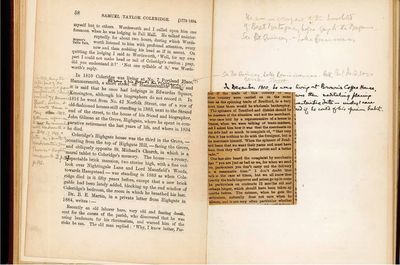

Facing pages from my own current case of curious provenance are reproduced above. They come from a book I bought a while ago, for a whole pound less than J. C.'s Plexus volume: Literary Landmarks of London by Laurence Hutton.

Hutton was an American critic and collector (of death masks, among other things). Edinburgh, Florence, Jerusalem and Oxford were among the other cities covered in his "Literary Landmarks" series. Nothing if not of his age, Hutton notes that the authors of Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall "came to London in 1848, without male escort", and stopped at the Chapter Coffee House, No 50 Paternoster Row. Charles Dickens's last London home, 5 Hyde Park Place, long-since rebuilt, can be described here as "unaltered".

This particular copy shows that Hutton's series enjoyed some success: it's from the "revised and enlarged" fifth edition of 1889. For some time, it appears to have languished at W. H. Smiths on the Strand, until a George Laish bought it, on August 23, 1935, and took the trouble to note the date inside.

It wasn't the first or the last "mark of ownership" these Literary Landmarks were to receive, as you can see ��� the volume has been irregularly updated with newspaper cuttings and notes in pen and pencil, continuing that process of revision Hutton himself carried on from one edition to the next. The most yellowed cutting dates from 1896 ("here we have to lament the loss of Leigh Hunt's house, 8, York-buildings"); others date from the 1980s. At least two snappers-up of unconsidered trifles contribute notes in distinctively different hands, perhaps out of a shared enthusiasm for this hobbyist's game, sustained over the best part of a century.

I don't think I'll be playing the game myself ��� Literary Landmarks only comes to mind now because I'm reviewing a couple of modern guides to literary Britain that, up to a point, follow Hutton's formula. The major difference being that these new books, by Nick Channer and Frank Barrett, do not take for granted that the reader knows much, or even anything at all, about the writers and the literary landmarks they visit. Introductory, sub-Wikipedia information bulks out both books, whereas Hutton is explicit about his not writing for those "who need to be told who Pepys and Johnson and Thackeray were, and what they have done".

Both Channer and Barrett will need updating one way or another; I should think there are already one or two review copies with instructive scribbles in the margin to set the game going again.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers