Banned Books Month Guest Post from Luke Reynolds: We Are All Icebergs

Every year in my middle schools classes, about the third day of school, I step up onto our radiator so I can point to a massive poster of an iceberg and talk about it with my students.

I begin with, “You are all icebergs. I am an iceberg. Every book we’ll ever read is an iceberg. ICEBERGS!” At this point, many students wonder aloud what is the matter with the thing in my head called a brain?. Some students allow their eyebrows to rise, understanding where we’re about to go. Some want to know if I have ever fallen off the radiator.

Puffin Classics Paperback Edition, March 2008

The iceberg analogy is incredibly useful when thinking of, reading, or talking about banned books. Because often, books are censored for what people label “outrageous” or “unacceptable” about the surface of the book. But deep down, way below the surface, every banned book I’ve ever read or taught has had, at its core, incredible incantations of love, empathy, and pleas for understanding and recognition.

Take Mark Twain’s THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN. When I used to teach 11th grade, I remember planning a field trip for our students to take a two hour bus ride from Connecticut to Harvard University, in Cambridge, so we could hear from renowned African-American scholar and educator Jocelyn Chadwick. She gave a riveting speech, followed by a funny yet piercing Q & A with our students. She defended the novel, talked about how it has been used as a powerful tool to fight racism and prejudice, and opened up about the controversy—coming from so many sides—about the novel.

Ember, Paperback Edition, January 2010

As Dr. Chadwick spoke, my eyes scanned the audience of my students, and on their faces I saw fascination. The novel’s controversial and heavily-banned history lit them up. The idea that a book could be thrown out of schools—historically, yes, but even recently as we’ve seen with Matt de la Pena’s remarkable book MEXICAN WHITEBOY in Arizona—does the opposite of stifling student interest and engagement. Instead, it enflames it.

My students in the audience that day wanted to know why people had banned HUCK FINN, who had fought against the bans, what Dr. Chadwick believed, what I believed, and—most importantly—what they believed.

Often, books like Huck Finn are banned because of their language. Even now, as I teach in a middle rather than high school, I see incredible books that I know students would love, yet I am also all too keenly aware of how many adults would see only as far as the language and stop there, not understanding the deeper purpose, message, and resonance of the book. Kids, it seems, have a far greater capacity to understand the core instead of stopping at the surface.

So before I climb down off the radiator, I explain some of this to my seventh graders, and I then ask, “Do we behave like icebergs?”

Consistently, their hands shoot up—ready to offer story after story, example after example, of why they do think we all behave like icebergs.

Blink, September 2015.

“This one time, my best friend kept saying she was fine but…”

“People dress like they are perfect and their faces say they have no problems but…”

“People don’t talk about ______________ but…”

And on and on. In a way, what we show one another all too often falls into that category of language. And language, all too often, has the power to obscure rather than elucidate. As George Saunders powerfully wrote about the genocide in Darfur, politicians wield language to hide atrocities and enable inaction.

In our day-to-day lives, we all sometimes wield language to hide our emotions and actions and thoughts.

In books, language acts as the tip of the iceberg, too. But there is one key difference.

With great novels—many of them banned—language is the first stop. Beneath the language, we have plot, and beneath the plot, we have characterization, and beneath characterization, we have tone, and beneath tone, we have mood, and beneath mood, we have soul. Every great novel has its own identity—its own soul. And while with one another we can obfuscate the deeper, truer identity we possess, with a novel that identity is there, on the page, waiting for us to uncover it if we only read with open minds and empathetic hearts.

With my students, I tell them that our 7th grade year is going to be all about this process of uncovering, reading with empathy and open-mindedness. And I remind them not to stop only at language. Not to see a word that is “bad” and think the whole book is “bad.” Not to hear a character’s comment and reject the deeper issues that character faces.

Because if we do, then we ban the book from speaking to us and reaching us and changing us.

We already do this far too much with one another. And one way to learn to censor and ban one another less and learn more is to practice with books. If we allow ourselves to hear the deeper story of a novel, empathize with its characters, live its plot, than the more we’ll learn to dig deeper with each other, too.

I climb down off the radiator, ready to begin another year of 7th grade literature and life. But before we stop talking about icebergs, I quietly share a secret hope with my students: that by the end of the year, more ourselves might stretch above the surface, more of who we really are might—however cautiously—reach up and reveal itself.

And beyond any state scores or testing or grades, if my students can learn to read beneath the first layer of language with books, and bravely risk more layers of themselves, than maybe as a classroom of learners we will all be a little less judgmental and a little more empathetic. And deep down in my own soul as a teacher and writer, this is the only standard I really care about.

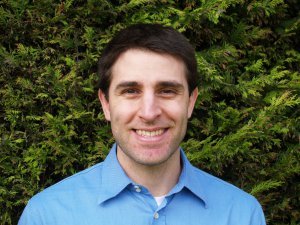

Luke Reynolds.

Luke Reynolds currently teaches seventh-grade English in the public school system in Harvard, Massachusetts. He and his wife, Jennifer, have two young boys and a young dog who is intent on waking up those young boys as often as possible. Luke is a lover of writing, running, pancakes, hiking, and all things goofy. His website is www.lukereynolds.com, and he blogs at reynoldsluke.blogspot.com. His previous work includes nonfiction such as: BREAK THESE RULES: 35 YA Authors on Speaking Up, Standing Up, and Being Yourself; A CALL TO CREATIVITY; and IMAGINE IT BETTER: Visions of What School Might Be.