dryly or drily, slyly or slily? A spelling conundrum

A young Zambian girl and boy smiling shyly.

What’s the issue?

The other day I was writing this sentence: “The exotically handsome man in the corner lowered his Arabic newspaper and smiled shyly at her.”

I had to pause to think about the spelling of “shyly”. Was that right, or should it be “shily”?

But the second one looked very, very odd to me. A quick check in the Oxford online dictionary (British & World English) confirmed that the -yly spelling was indeed correct.

How many words are affected?

That set me thinking, though, about which other adverbs were affected. The obvious one – well, perhaps not that obvious, because none of these words are/is particularly frequent – was dryly/drily, and the only other one I could think of off the top of my head was slyly/(slily?).

The OED has since come to my aid by adding wryly to those. It also lists two opposites (unshyly and unslyly) as well as some curiosities. (I’ve put a couple at the end. As so often happens, the OED citations suggest some delightful [to me, at any rate] historical asides.)

OK, aren’t I fussing about superminutiae, you might ask. Yes and no. There is a generalizable spelling rule that piqued my curiosity, and, apart from anything else, I wanted to refresh my understanding of it.

What’s the spelling rule?

That spelling rule, as formulated in the Oxford A-Z of Spelling, is:

“When adding suffixes to words that end with a consonant plus -y, change the final y to i (unless the suffix already begins with an i).”

Using its examples, that gives us pretty -> prettier -> prettiest

ready -> readily

beauty -> beautiful

The rules also apply to the inflectional verb morphemes -s, -ed, -ing added to verbs ending in -y, thus giving us, on the one hand, defy -> defies, defied, deny -> denies, denied, and on the other defying, denying.

Them be the rules. But there is a certain fuzziness affecting a few words apart from the adverbs already mentioned: dryer vs drier and flyer vs flier come to mind. And American and British usage seem to be different, as dictionaries illustrate below. So, it constitutes yet another of those trillions of subtle differences between American and British English that can flummox the unwary.

So, why are shyly, slyly, etc. exceptions to the rule?

The final letter -y of many adjectives – pretty, crazy, noisy, etc. – represents a ‘short’ unstressed i sound, i.e. /ˈprɪti/. When the adverb suffix is added, it changes slightly to /ˈprɪtɪli/ but it’s still an i sound. But the -y in shy, sly, etc. represents a different /ʌɪ/ sound, e.g. /ʃʌɪ/. The more common pattern for adverbs is the first (around 500 examples in the OED), which presumably sets up the expectation that the spelling -ily is to be pronounced /-ɪli/. And that just jars with what we know about the pronunciation of dry, etc. as an adjective by suggesting the anomalous /drɪli/.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

What do dictionaries say?

Oxford online (UK): drily (also dryly); shyly; slyly; wryly

Oxford online (US): dryly (also drily); as above

Collins online (UK): drily or dryly; shyly; slyly, slily; wryly

Collins online (US): dryly; shyly; slyly; wryly

Merriam-Webster online: drily or dryly; shyly; slyly also slily; wryly

OED unupdated entries give: dryly | drily and slyly | slily as alternative headwords; shyly (also shily); wryly (also 15-16 [i.e. 1500s, 1600s] wrily)

The Oxford Canadian dictionary gives dryly (also drily), whereas its Australian companion gives drily (also dryly).

(NB: there are also differences in what dictionaries show for comparatives and superlatives of adjectives, e.g. shyer/shier, shyest/shiest, but I’m trying to keep this short(ish), though I inevitably end up being prolix.)

Historically, it looks as if writers have for a long time wavered between the two spellings. For example, the 14 OED citations for dryly/drily divide into dryly (5), drily (7), driely (1), dryely (1).

Take Our Poll

Corpus to the rescue

Oxford English Corpus (OEC) data (March 2013), which covers ten varieties of English, produces 1980 citations for dryly, against a mere 416 for drily. In most varieties where the figures can be taken as meaningful, there is a clear preference for dryly, most markedly in US English, closely followed by Canadian. Only British and New Zealand English show an almost 50/50 split.

(Complete table at the end; apologies for the format: I can’t do WordPress charts.)

The Corpus of Global Web-based English does not show such an extreme split: dryly (437)/drily (231), but confirms most of the trends shown in the OEC, except: in NZ dryly predominates, and Irish usage is roughly 50/50.

There doesn’t seem to be too much online discussion of this minutia (yes, it does exist). In a posting on dryly/drily, a British speaker states that she prefers drily, while the original poster (sounds odd, but is correct) was puzzled by seeing drily in US publications. And an American professor was perplexed about how to explain this glitch in the rules to his class.

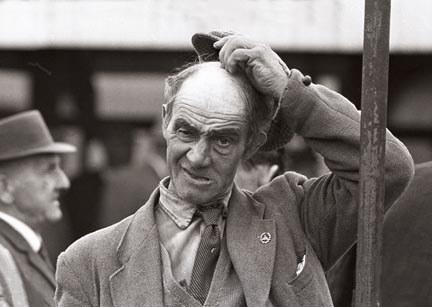

I suspect the spelling of this very small group of adverbs causes not a few people to scratch their head quite ferociously.

Man dryly scratching bonce.

Some OED treasures

I searched for *yly, which returned also vowel yly. All of these headwords are marked in the OED with the obelisk (dagger) symbol, to show that they are obsolete: †

astrayly (i.e. from astray), has only one citation, from the 1440 Promptorium Parvulorum (“storehouse for children”) a bibliographical landmark as the first bilingual English-Latin dictionary. It translates astrayly as palabunde, the adverb from the post-classical Latin pālābundus, “wandering about, struggling”.

Sundayly (i.e. every Sunday). From The Medieval records of a London City Church (1905) p. 110: Item payd sondayly to iij [3] poore almysmen to pray for the sowle of Iohn Bedham yerely.

It’s a touching image of medieval devotion to think of those three men being paid – or given something in kind? – to pray for John Bedham’s soul – but only once a year?

enemyly: from the Wycliffite bible (c1384) Macc. xiv. 11 Other frendis hauynge hem enmyly, enflawmiden Demetrie aȝeinus Judee.

Last, and certainly not least, from the 1496 epitaph of Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke and Duke of Bedford (Beddeford), buttly, which the OED defines as “beautifully (?)” : He that of late regnyd in glory With grete glosse buttylly glased Nowe lowe vnder fote doth he ly.

There are 31 citations from this work in the OED. Jasper Tudor was Owen Tudor’s son, Henry VI’s half-brother, and Henry Tudor’s uncle, and a powerful figure during the Wars of the Roses, instrumental in the victory of his nephew, who thus became Henry VII.

Totals for citations do not match overall figures given earlier, since low numbers of occurrences have been excluded.

Variety of English

dryly

drily

Total citations

Number

As % of total for that variety

Number

As % of total for that variety

US

887

91%

88

9%

975

Br.

259

54%

222

46%

481

Can.

54

89%

7

11%

61

Austr.

49

87.5%

7

12.5%

56

Irish

21

78%

6

22%

27

NZ

15

45%

18

55%

33

Unknown

677

92%

62

8%

739

Filed under: Advice for writers, Grammar, Spelling Tagged: American Spelling, US & British usage