Blog: Brown Beginnings, Issue 6

As the release of the non-fiction book The Boys in Brown approaches, author Jon J. Kerr takes readers inside the process. On Tuesdays, the series Brown Beginnings gives readers a behind-the-scenes look at the conception and reporting of the story. Thursdays, he blogs about the writing and publishing steps before launch.

On July 6, 1957, an English rock band named the Quarrymen finished a concert behind a Liverpool church named St. Peter’s.

After the gig, the lead singer of the Quarrymen, John Lennon, was introduced to an aspiring musician named Paul McCartney.

A few years later, the two teenagers formed a band called The Beatles. In 1966, The Beatles recorded a song titled “Eleanor Rigby.”

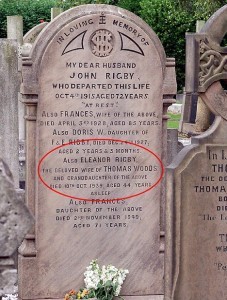

In a cemetery near the same church where Lennon and McCartney met almost 60 years ago, rests a gravestone. On that gravestone is carved the name Eleanor Rigby.

Credit: Sue Adair

Although Lennon and McCartney never directly attributed the inspiration for the song to the deceased Rigby, the coincidence is striking. Musicians often say how the subconscious influences their writing. It’s not a stretch to assume this landmark in a Liverpool cemetery provided a creative spark that led to one of the most famous Beatles songs in history.

I had a similar experience while reporting and writing The Boys in Brown.

Early in that season, 2010, I attended a Thursday night team dinner. The meal was hosted at the home of Luke Venegoni, a senior linebacker for the Corsairs. I had a good conversation that night with Luke’s mom, Claudia. On the way out, I noticed a picture frame containing a newspaper article on the inside. This is a brief excerpt from the book describing that moment:

She puts the picture book away. On a mantel in the front hallway is a picture frame, which contains a newspaper article. It’s a story on linebacker LaRon Biere. Claudia cut the article out and had it framed. She says she plans to give it to LaRon next time she’s at school. Which is in less than 24 hours.

In the article, LaRon talked about his adopted mother, Marion Biere. She had passed away earlier that year and LaRon had dedicated the football season to her.

I took note of what he revealed, and like so many anecdotes, filed it away as a “look into more later” story. It entered my subconscious.

In an earlier blog post, I wrote about how the first book draft featured the Carmel coaches as the main characters. An early editor, Peter Meyer, was the first to ask if there was more story to tell. His question jolted my subconscious. This was late summer of 2012. What I first learned of almost two years prior came crashing back into present time.

What about Marion? Who was she? Why did she do what she did?

Finding answers to those questions took me in a different direction with the project. I went from having what I thought was a finished book about a group of immensely loyal high school coaches to pivoting towards profiling a now deceased but while alive, a seemingly ordinary nurse and housewife from Ingleside, IL. Yeah, good luck making that interesting.

As a writer, all we really have is our curiosity. The ability to make something interesting out of the obtuse. A writer enters a place and, through his or her prism, brings a reader in. Think of Charles Dickens’ London. Or Alice Walker’s vision of a prejudiced rural south during the Great Depression. We might have our own ideas as to the sight, smell and sound of these locales. But what we want is the author’s version of that place. When a writer’s voice aligns with a reader’s imagination, magic happens. This is true with A Tale of Two Cities and The Color Purple.

As I researched Marion’s life, interviewed people who knew her, I became increasingly convinced that I needed to take readers into her world, to a different time and place. And by doing so, I could tell a more complex story, one not just about a sport, but about society and culture. Here’s another excerpt from The Boys in Brown, when a high school-aged Marion is exposed to racial inequality for the first time:

In 1947, Holy Child High School was still all white. The cultural belief at the time was that blacks were not on equal footing with whites. One year while Marion was at Holy Child, an incident mirrored this widely held discriminatory view. An African-American doctor, Dr. Smith, who lived in neighboring North Chicago, would see patients at St. Therese’s, a hospital founded in 1929 by the Servants of the Holy Spirit missionary sisters. Well-respected as a doctor and community leader, Smith had a daughter. As Aloys Wegener wanted for his daughters, Marion and Joanne, Dr. Smith desired a Catholic education for his daughter. But Holy Child wouldn’t accept her. Administrators came to the conclusion that accepting a black student would become a financial liability as the result of students leaving en mass, not wanting to share the same classroom as a colored girl. The school said it could not afford the risk.

When Marion found out, she told Joanne and her parents how unjust this decision was. How could they keep someone from experiencing the same education as her just because she was black? It simply wasn’t fair.

And at that moment, Marion vowed if she were ever in a position to right this wrong, she would.

Adding Marion’s story to The Boys in Brown was not obvious at first. But by mining the subconscious, and trusting my instincts, the book transformed into something more fully-formed. And as I began my second draft, it felt right. I can only imagine if John and Paul felt the same way while penning Eleanor Rigby all those decades ago.